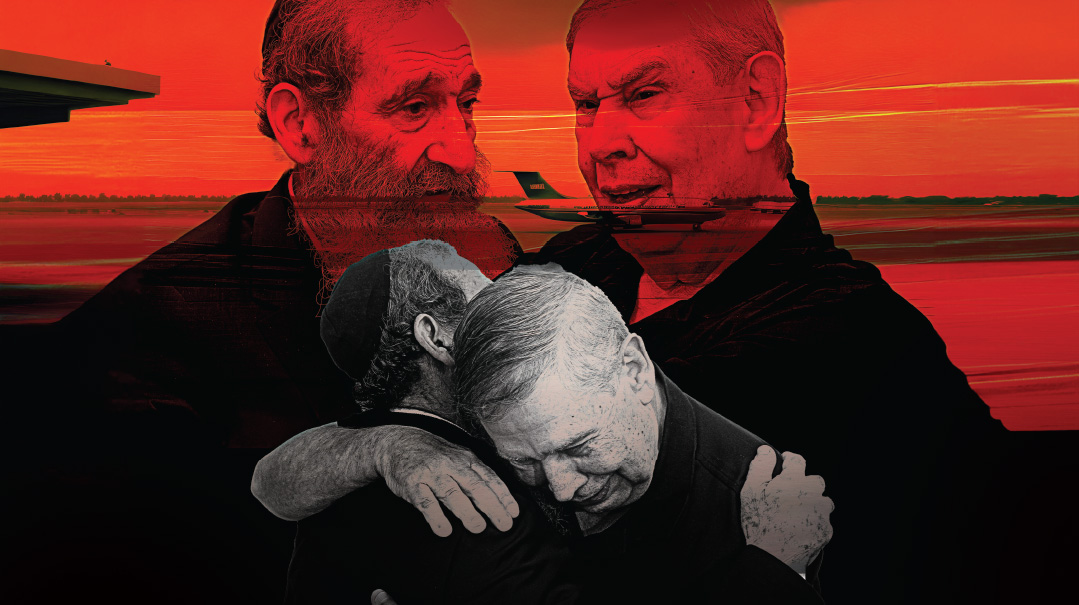

Torah of a Niggun

It’s a chassidus best known for its stirring melodies, but those tunes were the souls of the rebbes who wrote them.

The few hundred men fortunate to be at the Emunas Yisrael beis medrash in Boro Park the first night of Chanukah two years ago were treated to a Heavenly chariot ride: a classic Modzhitz lichttsinden. The Modzhitzer Rebbe of Bnei Brak — a guest of his dear friend, Emunas Yisrael mashpia Rav Moshe Wolfson — was joined by world-renowned Modzhitz composer and chazzan Rabbi Benzion Shenker for an hour of transformation: spiritual intensity joined with the power of niggun so typical of this chassidus. For Reb Benzion (then 88), it was one more adventure in the 70-plus years at the side of Modzhitzer rebbes; for the Rebbe, it was another expression of his link in a dynasty that has elevated the power of melody to a level of meditation and purification.

The Rebbe — Rav Chaim Shaul Taub — has led the chassidus for the past decade with a combination of his Ponevezh-trained, brilliant analytical mind and the heart of a Modzhitz niggun; now it’s Chanukah again, and within Modzhitz’s special Maoz Tzur, I can still hear the Rebbe’s Selichos of three months ago — it is said that the last day of Chanukah is the final reprieve for the judgment of Rosh Hashanah. Perhaps that’s why there is no derashah before Selichos in Modzhitz, none of the customary words of inspiration and introspection, no mussar seder.

“In Modzhitz,” an elderly chassid told me before Selichos in the Bnei Brak beis medrash (where the chassidus was transplanted 20 years ago after five decades in Tel Aviv), “hearing the Rebbe reciting ‘Ashrei yoshvei veisecha’ is enough to stir our hearts to teshuvah.” Minutes later, as I watched the leader of this holy flock pouring out words of the tefillos, it seemed as if the entire Modzhitzer shul had been transformed into a solid block of kedushah.

In Modzhitz, the chassidim tremble in fear of Heaven like everyone else, but here, it’s accompanied by song. Here, pious Jews — chassidim in spodeks and clean-shaven Litvaks in Borsalinos — give expression to that awe through niggunim crafted by the tzaddikim of the dynasty, from the first Modzhitzer Rebbe, Rav Yisrael Taub, to the current Rebbe — a venerated rosh yeshivah and also a mechaber of song in his own right.

It’s All Hefker

It would be difficult to imagine the world of chassidic music without Modzhitz. The founder of the Modzhitz dynasty, Rebbe Yisrael Taub of Modzhitz (known as the Divrei Yisrael), once commented, “People say that the world of music is closely connected to the world of teshuvah — but I say that they are one and the same.”

The Divrei Yisrael, who passed away in Kislev 1920, was known for his piety, his Torah knowledge, but especially for his musical prowess. He composed hundreds of niggunim, but the story of his most famous niggun, “Ezkera,” has become legend within the chassidus. It was composed in 1910 when the Rebbe — who was diabetic and had terrible sores on his feet — was sent to Karlsbad for the healing baths. Looking around at the beauty of the resort and thinking of Jerusalem in ruins, he created a niggun to the words from Ne’ilah: “Ezkera Elokim v’ehemaya… I remember Hashem and I groan, as I see every city built to beautiful great heights, but the city of Hashem has been relegated to the depths of purgatory…”

After many unsuccessful healing attempts, one of his feet became so infected that the Rebbe developed gangrene and the doctors determined that his leg had to be amputated to save his life. The Rebbe traveled to Berlin for the surgery, but because of his weak heart, it was impossible to anesthesize him. Throughout the excruciating surgery and recovery, the Rebbe entranced himself with various niggunim, and turning his head toward the window where he could see the vista of the city, he chanted “Ezkera.” The complicated composition — which takes over 20 minutes to sing — is carefully guarded by the chassidim and only sung on special occasions. Today the only way to hear “Ezkera” is to attend a yahrtzeit seudah for the Divrei Yisrael on 13 Kislev in a Modzhitz beis medrash — yet hundreds of other Modzhitz niggunim have made their way into the classic chassidic repertoire.

But Modzhitz is not only about music; as Rav Chaim Shaul Taub closes the first decade of his leadership, chassidim know that their scholarly rebbe has one definitive message for his flock — he teaches his chassidim to love Torah, but no less to love every Jew without any preconditions. “I believe,” says Rabbi Moshe Taussig, a Modzhitzer mashpia handpicked by the Rebbe, “that the Modzhitzer Rebbe absorbed all the sweetness in the world and just left a little for everyone else. Anyone who’s seen his smile has been captivated.”

According to Rabbi Taussig and other chassidim of the beis medrash, that sweetness was apparent long before Rav Chaim Shaul was appointed Rebbe. “His home was always hefker to everyone. Ask any Modzhitzer chassid on the street, and he’ll tell you that whenever he visited the Rebbe — who was then a rosh yeshivah and the son of the Rebbe — in his home, he would always see two homeless people sleeping in an adjoining room, and a few other miskeinim rummaging through the kitchen and taking whatever suited their fancy. At the Shabbos meals, the crowd of guests would spill out of the living room and the adjacent passageways, while the Rebbe himself personally served each guest his meal, accompanied by a radiant smile so that it was difficult to resist. Go ask the Rebbe’s children if they ever slept in their own beds during their childhoods.”

The gabbai, Reb Aryeh Backenroth, told me that in all his years with the Rebbe, he has never seen the Rebbe become angry at anyone or complain about anyone. He tells me that sometimes, he himself points out some infraction to the Rebbe, to which the Rebbe smiles his good smile and replies, “This too will pass.”

“The Rebbe told me that his own father, the Nachalas Dan [Rav Yisrael Dan Taub], told him in his youth, ‘You must commit yourself never to think anything about anyone that you would be ashamed to tell the person to his face.’ The Rebbe,” Reb Aryeh continutes, “has worked on himself so much that I believe it’s impossible for him to entertain a negative thought about anyone.”

Zeide’s Secret

Rav Chaim Shaul Taub was born in Adar of 5711 (1951), just three years after the passing of his great-grandfather, Rebbe Shaul Yedidya Elazar Taub. Rebbe Shaul Yedidya, known as the Imrei Shaul, fled Poland in 1938 and made his way to Japan, eventually reaching San Francisco and then moving to Brooklyn in 1940, where he rebuilt Modzhitz. He was a gifted songwriter and gave the chassidus its reputation for niggun. He also had an intense love for Eretz Yisrael but never realized the dream of aliyah — he was niftar on November 9, 1947, the day the UN voted to create the State of Israel. He did merit burial in the Holy Land though, as the last person to be buried on Har Hazeisim until it was liberated in 1967.

Chaim Shaul grew up under the leadership of his grandfather, Rav Shmuel Eliyahu (the Imrei Eish), who had been living in Eretz Yisrael since 1935. As cliché as it’s become to include in rabbinic biographies, young Chaim Shaul stood out from the very beginning. An older chassid shares a memory. “When the Rebbe was eight years old, air-conditioning was installed in the Modzhitzer beis medrash in Tel Aviv, donated by a wealthy Jew. The youngster was curious about the identity of the donor, and he asked his grandfather, the Rebbe, who it was that had made the contribution. The Rebbe replied, ‘I promised the donor that he would remain anonymous.’ The boy replied, ‘I’ll figure it out.’

“On Friday night after davening, the future Rebbe approached his grandfather and said, ‘The donor was so-and-so.’ The Rebbe was astounded. ‘How did you know?’ he asked.

“ ‘When the mispallelim arrived,’ the boy replied, ‘I watched to see which of them would not be surprised by the air-conditioning. I watched the men, and each of them was surprised and impressed. Only one of them showed no signs of surprise, so I knew that he was the donor.’ ”

The Rebbe was just 11 when, after skipping two grades, he left Talmud Torah Yesodei HaTorah in Tel Aviv to join Yeshivas Ponevezh Letzeirim, under the direction of Rav Aharon Leib Steinman. [At a gathering not long ago, Rav Steinman said of his former student, “Er halt zich a talmid — He considers himself my student.” “But the Rosh Yeshivah has thousands of students. What’s special about him?” someone asked. “Many students forget me after they become Rebbes,” said Rav Steinman, “but the Modzhitzer Rebbe never forgets.”]

Two years later, when he celebrated his bar mitzvah, it was a time of great rejoicing in Modzhitz, since Chaim Shaul’s father, the Nachalas Dan, was the only son of the Imrei Eish, and this was the bar mitzvah of the Rebbe’s eldest grandson. In honor of the bar mitzvah, the Imrei Eish composed the tune to the words ‘Baruch Hu Elokeinu shebaranu lichvodo’ that is sung to this day at virtually every Torah event in the frum world.

When he was 14, the future Rebbe moved on to the Yeshivah Gedolah of Ponevezh. During the entrance exam, Rav Dovid Povarsky posed a question on Maseches Gittin, daf Yud; the only bochur who could answer it was Chaim Shaul, to which the Rosh Yeshivah commented, “This is a blend of litvish and chassidish genius; the teirutz appears both in the Chiddushei HaRim and in the chiddushim of Rav Chaim of Brisk.”

Once, in the middle of a shiur, the chassidishe bochur asked a brilliant question, challenging the Rosh Yeshivah’s approach. The Rosh Yeshivah thought for a moment and quickly realized the profundity of the question: he closed his Gemara and announced that the shiur was over. Rav Chaim Shaul felt bad and toiled to come up with a resolution, but every time he tried to suggest an answer, the Rosh Yeshivah would dismiss it. “Your question is stronger than all the answers,” he kept asserting.

The Rebbe’s classmates relate that the Rosh Yeshivah once approached the Rebbe’s chavrusa and said, “Reb Chaim Shaul will be getting engaged tonight; you’ll see.” Of course, his prediction came true. The next day, he commented to the chavrusa, “You’re probably wondering how I knew. The answer is simple: Reb Chaim Shaul has never missed a morning seder. Since he was absent yesterday, I understood that a shidduch was in the offing.”

Indeed, the Rebbe married the daughter of the Alexander Rebbe, Rav Avraham Menachem Danziger, who admired his son-in-law greatly and insisted on rising to his feet whenever his son-in-law entered the room. The Alexander Rebbe encouraged Rav Chaim Shaul to put down his chiddushim in writing, offering to fund the publication of his seforim. Rav Chaim Shaul, though, did not want to go public with his Torah, and so the Alexander Rebbe turned to his mechutan, the Imrei Eish, in the hope that he would persuade his grandson to agree.

“My dear mechutan,” replied the Modzhitzer Rebbe, “just as people say that your son-in-law is a gaon in learning, he is also a gaon in simplicity, middos, and humility.”

After learning for several years in Lithuanian-style kollelim, Rav Chaim Shaul, then 30, was tapped by his grandfather to lead the yeshivah he was founding at the time. Yet just three years later, in 1984, Modzhitz was plunged into mourning with the passing of the Imrei Eish, who left behind a community of grieving chassidim, divrei Torah, and hundreds more musical compositions. The Imrei Eish was succeeded by his son, the Rebbe Rav Yisrael Dan, who led the chassidus for the next 21 years.

A Different Person

Rav Yisrael Dan’s years of leadership were a time of steady growth for the current Rebbe, both on a personal and public level. While the Nachalas Dan led his flock with paternal love, he also delegated many responsibilities to his son, among them running the chassidus’s educational system.

The chassidus of Modzhitz, in many ways, is a family more than it is a chassidic court, and Rav Chaim Shaul’s home in Tel Aviv was open to the many chassidim who came from Bnei Brak and from other locales to spent the Yamim Noraim and other holidays together with their spiritual leader; guests were admitted indiscriminately. He also made frequent trips to raise funds for needy families and for the institutions of the chassidus, although he never accepted a cent in remuneration for it, suffering poverty rather than accepting a commission or salary for the work.

On Sunday, the 14th of Elul 5765 (2005), Rav Yisrael Dan suffered a stroke. The previous Shabbos, the Rebbe had not been feeling well, and the gabbaim arranged a minyan for Shacharis in his home. His eldest son attempted to join the minyan, but the Rebbe instructed him to return to the beis medrash and receive the sixth aliyah, which is reserved for the Rebbe. “Take matters into your own hands,” the Rebbe said. In hindsight, the chassidim understood that this was a passing of the torch.

Rav Yisrael Dan’s illness lasted for nine months, until his passing on the 20th of Sivan. When the chassidim returned from his burial on Har Hazeisim, Rav Moshe Lerner, a senior chassid, announced that Rav Chaim Shaul Taub had been designated the fifth rebbe of Modzhitz. (Rav Chaim Shaul’s brother, Rav Pinchas Moshe Taub, was later designated as the Kuzmirer Rebbe.)

“Since then,” the chassidim relate, “the Rebbe became a different person. While he continued leading the chassidus with humility and remained closely connected with us, he suddenly seemed to have a special halo. ‘This is not the same man,’ said people who went to visit him for nichum aveilim.”

In keeping with the long-standing tradition of Modzhitz, the Rebbe composed 10 new niggunim for Rosh Hashanah of that year (2006), and continues to compose 12 new niggunim for every new year. “The tishen in Modzhitz suddenly became rejuvenated. Many people began flocking to the beis medrash to drink in the teachings of the Rebbe and to bask in his avodah of melody and song. Soon after, the beis medrash was expanded to twice its size, and we recently acquired a plot of land across the street, since the current beis medrash is too small to contain the growing chassidus. Under the leadership of the current Rebbe, additional shuls have been built in areas with a concentrated chareidi population, such as Modiin Illit, Beit Shemesh, Ashdod, and other cities.”

The Rebbe has made many rules for his kehillah with the intent of strengthening their Torah learning and building the community as a bastion of Torah and chassidus. Someone entering the beis medrash on a regular weekday morning might be surprised by the sheer number of men learning Torah in preparation for tefillah, in keeping with a special takanah that the Rebbe enacted when he first assumed his position.

About two years ago, the Rebbe opened a yeshivah gedolah named Tiferes Yisrael, designated for chassidish bochurim from both within Modzhitz and outside it. The yeshivah ketanah has also reopened and there is a new network of kollelim for the avreichim of Modzhitz.

Once, when a group of bochurim from Ponevezh came to speak with the Rebbe in learning, the Rebbe smiled and whispered to his gabbai, ‘You see, they have come to test me.’ ”

In sticking to his own self-imposed rules of humility and eschewing any luxury, it took years for the Rebbe to allow the chassidim to purchase a car for him. Whenever the Rebbe needed to go somewhere, there was always someone who would volunteer to drive him in a private car. Once, a Modzhitzer chassid saw the Rebbe being driven in an old, battered car belonging to an avreich in the chassidus. The philanthropist hurried to bring the Rebbe a check for NIS 80,000, promising to bring the sum up to a full NIS 120,000 so that a proper car could be purchased for the Rebbe.

The Rebbe replied, “It is almost Pesach now. I can manage. It would be better for you to give this money to avreichim before the holiday.” The philanthropist was forced to accept the Rebbe’s suggestion, and that NIS 80,000 went instead to the avreichim for their Yom Tov needs. Ever since then, the man donates a similar sum every year before Pesach, having learned the proper order of priorities from his Rebbe.

It was only after the Rebbe once arrived very late to a bris held by one of his chassidim due to the difficulty of finding someone to drive him, that he gave in to the pressure and allowed the very same philanthropist to buy him a car.

Like Old Friends

The Rebbe’s daily routine begins at 4:30 a.m. with tevilah in the mikveh located beneath the beis medrash. He spends the following two hours in solitary Torah study — he won’t start davening until he’s completed a full two hours of learning. The Rebbe’s hasmadah has been defining him since his days in Ponovezh.

After davening, the Rebbe receives visitors for a short time. From 9:00 until 2:00, the Rebbe learns with a chavrusa. At 2:00, the Rebbe has lunch and takes a nap on his chair for about 15 minutes, after which he resumes his learning until 4:30 in the afternoon. At that time, he begins his kabbalas kahal, which continues until midnight.

The Rebbe’s visitors at kabbalas kahal come from every sector of the populace — the anxious and broken hearted, businessmen seek his counsel, parents in need of guidance on chinuch and shalom bayis. Modzhitzer chassidim themselves make up only about 10 percent of the visitors — all of whom are greeted by the Rebbe’s trademark radiant smile most people reserve for relatives and old friends.

The Rebbe’s gabbai once asked him how he finds the strength to deal with the many visitors who arrive at his doorstep for hours on end, every day. The Rebbe answered, “In davening we say, ‘In Your Hand is strength and might, and it is in Your Hand to give greatness and strength to everyone.’ I explain the pasuk this way: Who has ‘strength and might’? Someone who ‘gives greatness and strength to everyone.’ When a person gives chizuk to other Jews, he receives a Divine gift of vitality and strength.”

Despite his own sharp mind, the Rebbe’s advice is invariably straightforward; he always prefers simple logic to convoluted reasoning. If a chassid wants to buy a car, the Rebbe might tell him, “Go ask Reuven what type of car he owns; he has no problems with it. You can tell him that I sent you.” The Rebbe treats every sh’ailah that is brought to him with the same degree of seriousness he would apply to a matter of life or death. He asks for details, examines every side and angle of the question, analyzes the matter carefully, and then makes a precisely calculated decision. But when a chassid recently told the Rebbe that in spite of his efforts to earn a living, his expenses are still greater than his income, the Rebbe said, “I have nothing to advise you. You will have to call on your faith in Hashem.”

In his own yeshivah, the Modzhitzer Rebbe is heavily involved in the lives of the students. If the public phone in the yeshivah rings and no one else picks up, the Rebbe won’t hesitate to answer. One time he identified the caller as another bochur in yeshivah. “This is Chaim Shaul Taub,” the Rebbe began. “Regarding the answer I gave you yesterday when you were here, I came up with a better idea for you.”

Although Modzhitz is known as the “singing chassidus,” the Rebbe doesn’t approve of these holy niggunim being used outside the context of its sublime avodas Hashem. He disdains those “Modzhitz Music Evenings” held at cultural centers, where the music is stripped of its sublime tafkid and brought into the realm of the secular.

Most of the Rebbe’s annual compositions stay within the walls of the beis medrash, but some, like the rousing tune to the words “Zechor ahavas kedumim” have become popular throughout the chassidic world. And the Rebbe’s head is like a bank for the thousands of niggunim that have been composed by the zeides, ready to be withdrawn in an instant.

I ask the Rebbe’s closest associates if they know the secret to his musical genius. Does he need any sort of special inspiration to compose a niggun?

“Well, the Rebbe composed the tune for ‘Slach na la’avon ha’am hazeh’ in Selichos right after he found out that the kever of his ancestor, Rav Yechezkel of Kuzmir, had been located,” the gabbai says.

In the months of Av and Elul, the Rebbe begins crafting his niggunim for the Yamim Noraim. One of his chassidim, Reb Ezriel Lerner, listens to each niggun, records it, and passes it on to the members of the choir. At the same time, Reb Avraham Backenroth, who knows how to write music, quickly records the Rebbe’s work on paper.

“Simchas Torah,” says Rabbi Taussig, “is the Rebbe’s holiday. Several years ago, the Rebbe made a takanah for all the bochurim of the chassidus to learn an amud of Mishnah Berurah every day. On Simchas Torah, he told them all to dance while holding the volumes of the Mishnah Berurah, just as they say that Rav Meir Shapiro danced with volumes of the Gemara after he instituted the daf yomi. The Rebbe once told me, ‘It pains me when people think that Modzhitz is a chassidus of singing. Do people everywhere else sing less than in Modzhitz? Modzhitz is a chassidus of Torah!’ ”

The Final Niggun

The Modzhitzer Rebbe is a rebbe for the Litvaks as well, according to his good friend Rav Shalom Ber Sorotzkin.

“Every year,” Rav Sorotzkin relates, “we invite the Rebbe to deliver a shiur in the Ateres Shlomo kollel network. The first time the Rebbe came to deliver a shiur at our kollel in Kiryat Sefer, there were a few litvishe avreichim who found it difficult to digest the fact that a chassidish rebbe was being brought to address a beis medrash of 1,000 litvaks. They prepared a series of scintillating lomdishe questions to challenge him. Within minutes of the beginning of the shiur, they tried to debunk the Rebbe’s approach by asking, ‘What about Reb Chaim?’ Before they could even finish their question, the Rebbe replied, ‘Which Reb Chaim are you referring to? The Reb Chaim in Hilchos Tumas Meis, in Hilchos Chanukah, or in Hilchos Shabbos? If you’re referring to Hilchos Tumas Meis, it’s the subject of a dispute between Rav Boruch Ber [Leibowitz] and Rav Naftali [Tropp]. If you’re referring to Hilchos Chanukah, there is a difference between the Brisker Rav and the Avi Ezri in their understanding of the question. And regarding Hilchos Shabbos, there are two pieces in Rav Baruch Ber that deal with it.’ Well, that was both the first and last challenge those avreichim presented.

“More than anything else, the Rebbe has been blessed with a rare type of wisdom that makes it possible to consult with him on any subject,” Rav Sorotzkin continues. “We’ve known each other for 15 years, and I can tell you that I’ve asked him many questions, and never regretted seeking his advice. His wisdom, his clarity, and his ability to distill an issue down to its fundamental essence are highly unusual.”

Rav Sorotzkin, although a Litvak through and through, shares one more thought. “I try to attend every tish that’s held during the week, and I am not the only Litvak there. The Rebbe is the only chassidishe rebbe I know who has maintained his ‘litvishe lomdus’ to this day. He also has that unique chassidishe warmth and the dedication to the ways of his forebears. It was once said that Modzhitz is ‘the lomdus of niggunim,’ but the current Rebbe is a master of lomdus both in Torah and in niggun.”

Perhaps that explains the power of one of Modzhitz’s most famous niggunim, the “Ani Maamin” that accompanied a trainload of Yidden on their final journey to Treblinka. Many are familiar with the story of Reb Azriel Fastag, a Modzhitzer chassid and baal tefillah who was known throughout Warsaw for his exceptional voice. The Modzhitzer Rebbe Rav Shaul Yedidya Elazar had already managed to flee as his chassidim smuggled him out of Poland, but now the trains were transporting tens of thousands of Jews to their deaths every day.

In one cattle car, though, Reb Azriel began singing the niggunim of the Rebbe on Yom Kippur, imagining himself praying next to his rebbe, when suddenly the words of “Ani maamin b’emunah sheleimah, b’vias haMashiach…” appeared before him, and he began to hum a tune. “How can you sing at a time like this?” accused some of his fellow travelers, but soon the niggun caught on, and in the face of death al kiddush Hashem, the entire doomed boxcar was soon joining in. Reb Azriel quickly scribbled down the notes and looked around. “My dear brothers!” he exclaimed. “This niggun is the song of the Jewish soul. It is a song of pure faith, for which thousands of years of exile and troubles cannot overcome! I will give my portion in Olam Haba to whoever can take the notes of this song to the the Modzhitzer Rebbe!”

Two young men met the challenge, promising to bring the notes to the Rebbe. One of them climbed on the other’s shoulders, and in the small crack of the train’s roof, made a hole large enough to jump through. The two jumped. One was killed instantly from the fall, and the other somehow survived, eventually making his way to Eretz Yisrael, from where he sent the notes by mail to Rebbe Shaul Yedidya Elazar in New York.

“When they sang ‘Ani Maamin’ on the death train, the pillars of the world were shaking,” the Rebbe said after receiving the notes and having the niggun sung. “With this niggun, the Jewish People went to the gas chambers. And with this niggun, the Jews will march to greet Mashiach.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 588)

Oops! We could not locate your form.