Too Much of a Good Thing?

| March 4, 2020For children who don’t truly need those services, the effect can actually be crippling

A

It was in the beginning of a school year when I met with Mrs. Kaplan, a young mother of three children who I knew from my neighborhood. She had requested that her two-and-a-half-year-old Moshe be evaluated. Moshe had attended a pre-nursery classroom in a local school for a few months, and would be continuing in September. I was familiar with his school and with the agency providing services in that school. Mrs. Bender was the coordinator there.

“So why are we having little Moshe evaluated?” I asked her, ready to document her concerns.

“Well,” Mrs. Kaplan started, “The school recommended I have him evaluated as Moshe has allergies, and he gets eczema when he eats what he isn’t allowed to. He needs a health paraprofessional in the classroom with him.”

I typed as she spoke. “Has he ever stopped breathing? Does he carry an EpiPen?” I inquired.

“No, it’s just the eczema. Do you think he will qualify?” she wanted to know.

“Well,” I explained to her, “In the years I’ve been doing this I’ve never seen a child receive a para for such mild allergies, as the Department of Education usually provides such costly assistance only for life-threatening situations. However, if you’d like, we can go through the process and see if you’ll be approved.” I didn’t want to push Mrs. Kaplan either way, as that’s not my place. “Do you have any other concerns for Moshe?”

“Yes.” she replied. “He also can’t pronounce a few sounds, such as the s, th, sh, and a few others. Do you think he can get speech therapy?”

I paused from my typing. Again, I explained to her that Moshe would have to qualify according to the standards set by the DOE. “If he has some language deficits, I’d have to see his speech results to know if he will qualify.”

At this point Mrs. Kaplan took a minute to think. “Hmmm. He doesn’t really have any language concerns. And really, he is getting much better with his allergies. I mean, I noticed he tells his grandmother what he is and isn’t allowed to eat. I wonder if I should even continue this process.”

“Listen,” I advised her, “it’s your call. If you’d like to go ahead with the evaluations to make sure he is age-appropriate, we can do that, and if you’d like to close the case, that’s perfectly fine as well. Either way, it’s up to you.”

“Aha, I see.” She paused. “You know, I think my Moshe is really fine.” She paused again, taking some more time to think, toying with a paperweight on my desk. “Yes, he really is, he hasn’t had eczema in a while. I think I do want to close the case.”

“No problem. I’ll have the secretary assist you with a closing letter. You’ll need to sign it and we’ll send it to the DOE.”

Mrs. Kaplan thanked me for my time, and gathered her belongings to leave. Although most cases progress to actual evaluations, parents sometimes do reconsider — and so I didn’t give the interview a second thought.

Until my secretary Dina called me the next day.

“Esther, I just got off the phone with Mrs. Bender. She is quite upset. She can’t believe we let Mrs. Kaplan close the case! She says the child definitely needs therapy and must be evaluated.”

This was a pretty strong reaction, considering his concerns had been so minimal. I decided to call Mrs. Kaplan.

“Hi, Esther,” she said as she picked up the phone, sounding a bit defeated. “I’m assuming you’re calling because you heard from Moshe’s school?”

“I did. But why don’t you tell me in your own words what exactly is going on?” I suggested.

“I don’t know. Honestly, I never knew the teachers in his playgroup had any concerns. I mean, they told me he was fine for the few months he was there. Now the school is telling me he doesn’t always listen and he needs a teacher with him in the classroom, aside from a speech therapist and para. I'm so confused. He’s only two! Isn’t that part of the teacher’s job?”

I listened quietly. It wasn’t my place to convince her to do the evaluations or not. I knew the school wanted her to pursue the evaluations, yet she as a parent had the ultimate final say.

Or rather, she should have had the final say. “But… I don’t know what to do,” Mrs. Kaplan sounded so lost. “Until the other day I was confident that my Moshe is fine. But how can I not listen to the school? I don’t want them to be upset with me. I guess I don’t really know what’s best for my child.”

At that point, I felt I had to intervene. “Mrs. Kaplan,” I said, “you know more than anyone what’s best for your child as you have a G-d-given mother’s instinct. I can’t tell you what to decide, but one thing I can tell you is to never stop trusting yourself.”

“I hear that. I’ll discuss this with my husband and get back to you with our decision.”

The next day, Dina emailed me that Mrs. Kaplan would forge ahead with the evaluations.

It’s not uncommon for young mothers such as Mrs. Kaplan to receive a phone call from their school, suggesting that their child be evaluated. And they agree, not wanting to risk being labeled “the difficult mother,” or worse, being asked to remove the child from school.

I’ve seen parents quietly shut down their inner voice, the one that knows what’s right for their child. But often, it’s too risky to give that “non-professional” voice too much credence. So the school sends her to therapists, the ones who have all the techniques and tools to fix all the little Moshes.

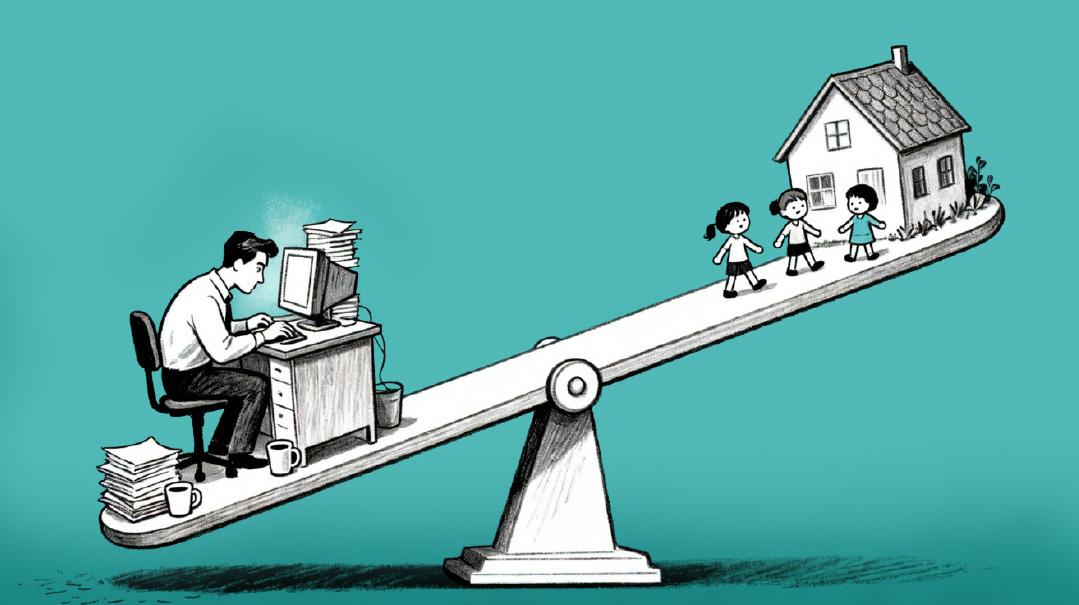

And so, we’ve morphed into a generation of unconfident parents — mothers who don’t trust their intuition, fathers who don’t trust their chinuch. We are scared of our children, frightened lest they fail, unsure how to raise them. Our parenting instincts have been squelched, as we run from one professional to the next, seeking that ultimate solution.

Of course, the world of therapy is vast, offering countless tools to greatly benefit and enhance the lives of those children who truly need it. But what about those who don’t need it? And what’s driving the schools to push for those evaluations?

Consider the following story.

I received a phone call from Mrs. Safar, a coordinator at one of the Head Start kindergartens, just weeks after school started. We had conducted evaluations for a three-year-old named Sara Berger. “I read through the evaluations,” she explained, “and noticed that Sara was noted to have a hard time engaging in conversation or play. Why wasn’t further evaluation, such as an OT and neurological evaluation, recommended, or a diagnosis of sensory processing disorder included?”

“I hear what you’re saying,” I responded. “Let me check into it.” While she was waiting on the line, I selected the child’s case and opened to the psychological report. Abigail D. had done this case. She was a very trusted psychologist, and had been doing evaluations for our department for more than a decade. She was thorough, dedicated, and hardly missed a thing. Her reports always included a detailed teacher report, as well as a thorough description of the testing.

Although the report did mention that the child was difficult to engage, and was reserved rather than social, this was not alarming for a three-year-old child spending time with an unfamiliar adult. Hardly an open-shut case of sensory processing disorder. Many other symptoms of SPD, such as lack of coordination, difficulty with spatial awareness, and more, had not been reported or observed by the psychologist or teacher. As it was, this case was already at the DOE; the evaluations had already been read by an administrator.

I decided to reach out to our Abigail, to double check her protocol sheets and see if she had missed any points when writing her report. While she remembered Sara’s lack of engagement, she had not felt that there was any indication that a diagnosis of SPD would apply, and had not recommended further evaluation.

“Esther,” Abigail said, “this child struck me as an average child with some mild concerns, but neither mom or teacher shared any other concerns related to sensory processing disorder, although they did share concerns about social development.”

I thanked Abigail for her time and dedication, and called Mrs. Safar back.

“Mrs. Safar,” I asked her, “is the mother concerned about SPD? Is the teacher concerned? Because when we did the evaluations a couple of weeks ago, these concerns were not mentioned to our evaluator. I do understand the child is reserved and shy, but that’s hardly a reason to jump to SPD.”

Mrs. Safar continued to insist the child likely had a sensory processing disorder and wanted Sara recommended for neurological testing, as well as an occupational-therapy evaluation.

“In good conscience, we cannot recommend or refer for something we didn’t see,” I told her. “If you’d like for me to reach out to Sara’s mother and see if she has concerns, I can do so, but the evaluation as it took place doesn’t change.”

She did not want me to reach out to Mrs. Berger. She wanted Sara diagnosed, so that she would be approved for a larger amount of services.

At the meeting the following week, I was astounded. Mrs. Safar provided an observation done by one of their staff, in which it was detailed that Sara was observed bumping into furniture, exhibiting difficulty with spatial awareness. The teachers had shared new concerns, including difficulty with tolerating noise and textures, such as touching glue. These concerns had not existed a mere few weeks ago.

Sara was approved for multiple services in the classroom, as well as a neurological evaluation. And although Sara’s mother, an intelligent woman, had not had any concerns of SPD whatsoever, by the time the meeting was over, Mrs. Berger was worried. She agreed to have the neurological evaluation, and was relieved her daughter would be receiving so many services.

In the quest to achieve more and more therapy hours and fill therapy slots, have we lost sight of the all-important goal — what’s actually best for the child? If a child has only a slight possible delay, the parent is advised to have them evaluated. If a three-year-old doesn’t want to touch glue, we run to occupational therapy instead of offering alternate crafts material. Are we fostering dependence on therapists rather than letting natural skills develop? Forget believing in a child’s natural capabilities — in an effort to secure more and more services, the push for therapy is heaped on parents, going to extremes of labeling children with conditions from SPD all the way to the autism spectrum.

Yes, there are children that need services, and for them the world of therapy is an invaluable tool to help them grow. Yet for those children who don’t truly need those services, the effect can actually be crippling — encouraging children to depend on the therapist instead of tapping into their own innate abilities, and giving parents reason to label their child as handicapped, often erasing their empowering trust in a child’s natural strengths.

A summer camp teacher once shared an interesting observation with me. “I can tell which children receive services during the year. When we do crafts in our four-year-old group, many of the children who receive services — most of them average kids — have learned that they don’t need to listen out for group directions, and instead need me to come over to give them individualized instructions. These are children who have no innate issue understanding basic explanations, yet they’ve been trained to rely on individual hand over hand instructions. They literally need me to hold the scissors for them.”

The writer can be contacted through Mishpacha.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 801)

Oops! We could not locate your form.