To the Highest Bidder

What auction house owners come across daily, in their quest for the rare finds they’re happy to pass on

David Knobloch of Spring Valley, NY, opened Rarity Auction House 3 years ago.

Fast stats: Depending on inventory, we have about six auctions per year. Three of those are “big ticket” auctions, but even at the “cheap” auctions, where everything starts at $25, some items will sell for thousands.

How I got started: My father’s been an antique dealer for 25 years. As a teenager, I used to go with him to customers and libraries and watched as he grew his collection. I later worked for an auction house. Most Jewish auctions are in Israel, but the customer base is in the United States and Europe. I opened my own auction house here in New York so Americans could come in, inspect a piece personally, and take it home without waiting for their finds to cross the ocean.

Fascinating finds: We once had the original document that appointed Rabbi Yitzchak of Radvil, the son of the Maggid of Zlotshov, as rabbi of the city in 1819. It sold for $50,000. In our last auction we had a letter inviting the Satmar Rebbe to England after the war, signed by all the European rabbanim. We put it up for $4,000 but it went for close to $30,000.

In our next auction, there’s a first edition of the Frankfurt Sefer Tiferes Shmuel from 1696. It contains many signatures, and the inscription: “I got this from my chavrusa, son of the author…” This was the personal copy of the Tiferes Shmuel’s only son, Rabbi Tzvi Hirsch Kaidanover (1648–1712), author of the Kav Hayashar, one of the most popular works of mussar in the last three hundred years.

FAQs: “Do you have anything from the Chasam Sofer?” “What chassidic items do you have?” “Any segulah seforim?”

Best fake: I primarily deal with seforim and manuscripts, so by now I can tell immediately what I’m seeing. Signatures need more investigation. I go to experts for authentication.

What I’ll never sell: I collect items that belonged to my grandparents. Whenever I see something on the market that belonged to my great-great-grandfather, Rav Adoniyahu Schmeltzer, I end up fighting for it with my uncle Lipa Schmeltzer, who’s also an avid collector.

Recently, I heard of someone who’d bought thousands of kvittlach that were given to the old Satmar Rebbe, Rav Yoel Teitelbaum. He’d even created an excel sheet of the kvittlach. I asked him to check for my family names. Turned out my other great-grandfather, Rabbi Naftali Weisberg, had sent one from Eretz Yisrael right after the war. I have that original kvittel framed on my desk. It’s priceless to me — I’d never sell it.

Effect of Corona: It was harder to meet people and look for items, but the online auctions weren’t affected at all. Maybe the stimulus checks helped….

Most surprising: Recently, I had seven volumes of a Shulchan Aruch with thousands of glosses from a talmid chacham called Rabbi Yair who lived before the war. It took me months to research the family. An hour before the auction, I got a call from someone in Canada who’d randomly googled his family name and found our catalog. In fact, his mother Yaira was named after the gaon Rabbi Yair. It was the man’s grandfather! It’s so exciting when items come full circle like that.

Tips: Don’t throw anything away. Call me, I’ll look at your old books with pleasure. Items worth millions have been buried with sheimos because people didn’t know. Other times, items aren’t valuable but it’s important to their owners that these old items still be used. I can help with that too.

Sharon Liberman Mintz has been the curator of Jewish art at the library of the Jewish Theological Seminary for 33 years. In 1995, she became the senior consultant of Judaica items at Sotheby’s New York.

Fast stats: Sotheby’s was founded in 1744 in London. It now has 80 branches around the world and holds hundreds of auctions per year. The first dedicated Judaica auction was held in 1949, with one to two sales every year since the 1970s.

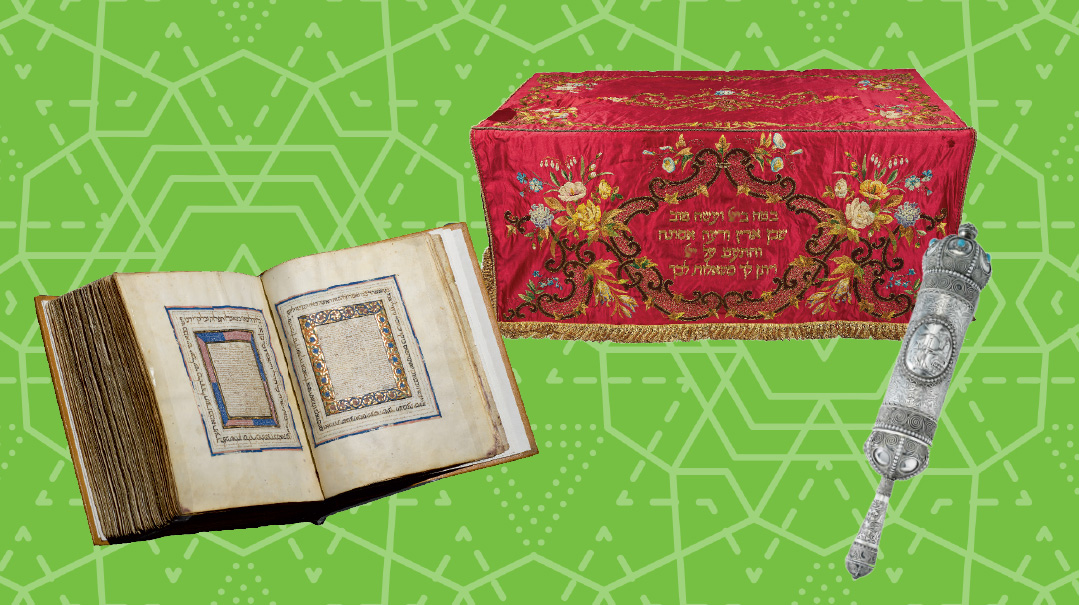

Fascinating finds: A decorated Hebrew Bible from 14th-century Castille, Spain sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and an illustrated Mishneh Torah from the 14th century that was bought jointly by the Israel Museum and Metropolitan Museum of Art. Both were sold before the auctions for between four- and six-million dollars. When there’s tremendous demand, items can be removed from the auction and sold privately.

Memorable stories: I recently sold an Italian bimah cover from 1865. After hours of research, I discovered the identity of the woman who had embroidered it, who she’d married, and which synagogue she’d donated it to. Interestingly, there is a special Mi Shebeirach recited in Italy every Shabbos morning praising women who created the textiles for the synagogue. To discover this entire parshah in Jewish history from just a single bimah cover is incredible.

Funniest fake: Someone got a hold of a reference book of illustrated Hebrew manuscripts, then photocopied pages onto old parchment, buried them, dug them up, and sent photos to every single Sotheby’s office around the world with a tale about discovering it on a construction site in the Far East. I guess they didn’t know that all their “discoveries” were being forwarded to the same person — me! I even know which book they made the photocopies from — that was pretty easy to spot. Having seen thousands of books and manuscripts, I know what to look for, but there’s also a scientific way to authenticate the age of an object with carbon-14 dating that can be helpful too.

FAQs: “How much is this worth?” People are always disappointed when hundred- to two-hundred-year-old seforim aren’t as monetarily valuable as they’d hoped. Most printed material needs to be from the 16th century or earlier to have a strong monetary value.

What I’ll never sell: I’m uncomfortable selling anti-Semitic material as it’s related to so much horror and destruction, even though there is historic value in it.

Where you find items: When people empty their great-grandparents’ apartment, they’ll sometimes discover valuable items that were handed down for generations. Sometimes it’s more random. Once a man brought in a picture frame that his wife purchased in a small store for $100. He was upset it cost so much, until he noticed the paper that was inside, and wondered if it was worth anything. The hand-drawn picture inside, from the 18th century, was a micrographic artwork — where the image is formed out of tiny Hebrew script — worth $22,000.

Effect of Corona: Coronavirus actually boosted sales. The Sassoon Family Collection was originally slated to be auctioned in June 2020, but as we were going to press with the catalogue in March, the world shut down. We rescheduled for December and were concerned how it would do. Ultimately, it was the most successful sale I’ve ever had, achieving in total double the low estimate. There were buyers from around the world, and 35 percent were new buyers. I guess people had more time to look at things online.

Tips: If an item’s been handed down in the family, that’s a good sign, especially if it’s silver. A piece of Bezalel art created in Israel in the 1920s is usually good news too. Take close pictures, measure the dimensions, and take note of silver marks. You can send your info to Sotheby’s without any commitment and within two weeks you’ll hear back from a team of experts as to its value.

Yehuda Schwartz, a native of London, is the owner of Legacy Judaica, which is located in Lakewood and has two large auctions per year.

How I got started: As a child, I was always fascinated by antique seforim, rabbinical correspondence, and Jewish history. I loved sifting through the sheimos box in shul and bringing home all kinds of “treasures.” As an adult, I wondered if I could make a parnassah from my childhood pastime. My first sale was a letter written by Rav Yehuda Assad to Rav Mendel of Deyzh. After a few years of dabbling, I was contacted by a yungerman who’d purchased Rav Ruderman’s entire seforim collection, which included thousands of rare volumes. At the same time, a family who’d inherited a magnificent collection of rabbinicial manuscripts asked for my assistance selling them. The yungerman and I partnered and founded our own auction house. A while later, he moved out of town and I bought him out.

Fascinating finds: A sefer called Refuas Ha’am printed in Zolkiew in 1794. It’s essentially a first-aid book with an approbation of the Pri Megadim, with many handwritten glosses, including some by Rav Baruch Frankel Thumim, one of the most famous Acharonim and author of the sefer Baruch Taam. Later, we actually found an inscription in the binding with Rav Thumim’s name.

Other amazing discoveries include a Haggadah with an inscription by the Chidah, a Shulchan Aruch Pri Megadim with hundreds of glosses written by Rav Yisrael Lipchitz (author of the Tiferes Yisrael), and part of a Chumash printed in Spain before the expulsion.

Most chilling discovery: A Slavita Chumash Chok L’Yisrael that belonged to Rabbi Shalom Eliezer Halberstam of Ratzfert, the second-youngest son of the Divrei Chaim of Tzanz. He was murdered in Auschwitz at age 84 and was not zocheh to a kever. Inside the Chumash were white hairs, likely from his beard….

How you authenticate: I take seforim and manuscripts to Rav Shmerel Zittronenbaum, the well-known Bobover chassid who published the Torah journal Kerem Shlomo. He can look at handwriting and tell which Acharon wrote it. Hundreds of people and hundreds of thousands of dollars depend on him certifying a signature… or not.

FAQs: “What is my item worth?” People are often surprised that there are other factors that determine an item’s value, aside from age. There were also great leaders who were considered gedolei hador of their time who are unfortunately hardly known today.

Favorite story: Many years ago, Rav Zittronenbaum found a Gemara in a shul in Khust, Hungary, with handwritten chiddushim in the margins. While leafing through it, he discovered a small, folded paper: a prewar receipt for a few kroner from a kimcha d’Pischa fund written to Rav Refoel Zilber, the Freimaner Rav (1904–1996). The Freimaner Rav had lost his entire family in the Holocaust and was then living in New York. Rav Zittronenbaum was able to return those long-lost chiddushim to him. Amazing that it was a decades-old donation, the receipt of which he’d just “happened” to use as a bookmark that was the catalyst for this emotional reunion.

What I’ll never sell: I keep far away from items that have family disputes about ownership.

On collectors: Years ago, most collectors were traditional Jews, but today there’s increased interest from the frum crowd.

Tips: Look out for first editions of classic seforim, particularly chassidic seforim. Rabbinical correspondence can also be extremely valuable.

Massye Kestenbaum, together with his brother Zushye, helps operate the New York-based family-run Kestenbaum & Company, which their father Daniel founded in 1996.

How I got started: I was drawn to the field of rare Judaica by a passion for Jewish history. Each object we handle tells a different story of a time and place in our past. For example, I was just working on a copy of a special tefillah for the welfare of Maria Theresa, empress of Austria, written in 1756 by Rav Yechezkel Landau, the Noda Be’Yehudah. Maria Theresa was a huge anti-Semite. Only a few years before this tefillah was written, she’d kicked the Jews out of Prague. What was the context of this prayer?

On location: Our company headquarters recently relocated to the new development in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Interestingly, during World War II, the then-future Lubavitcher Rebbe worked there for the Navy, helping construct the USS Missouri.

Fascinating finds: An elderly woman from a small town, whose grandmother had hailed from an important Breslov family in Jerusalem in the early 20th century, approached us with a Hebrew letter written by an ancestor more than a hundred years earlier. She couldn’t read Hebrew, and for years the letter had been gathering dust in the closet, until thieves broke in and ransacked the place. While surveying the mess, the elderly woman noticed the letter and finally decided to find out more about it. My father took one look and was shocked: It was written by Rav Noson of Nemirov, Rebbe Nachman of Breslov’s talmid muvhak.

Rarest item: My father was once evaluating a library when he found an old, worn manuscript. His interest piqued, he looked into it more, and ultimately discovered it was a 700-year-old handwritten copy of Rashi, one of the oldest that exists today.

How you authenticate: My father can authenticate 99 percent of the material he sees. Occasionally, we call in a subspecialist, if needed.

What I’ll never sell: Nazi memorabilia. It has no place or relevance to us.

Also, just as important as what we sell is how we handle what we do sell. Manuscripts from Rambam or the Chofetz Chaim, the earliest printed Gemaras, or the first set of Tosafos Yom Tov — these aren’t commodities like luxury cars or signed baseballs, l’havdil. There are halachos that discuss selling kisvei kodesh, especially sifrei Torah, ensuring that when such sales take place, they are done with the utmost kavod and dignity.

On collectors: Just like there’s no typical profile of a Jew, there’s no typical profile of a Judaica collector. There are all types, from all over. Everyone here is united by a mutual love for our past… and a joint concern for our present.

Tips: Think of the story your item tells. Where was it made? Who owned it? What historical events did it “live through”? What’s unique about it? Sometimes the story isn’t so important, but generally, it’s unique items with stories that make a compelling addition to any auction.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 854)

Oops! We could not locate your form.