To Lift Up the World

| November 21, 2023Too often, I see parents and teachers “pushing” those in their care instead of supporting them

W

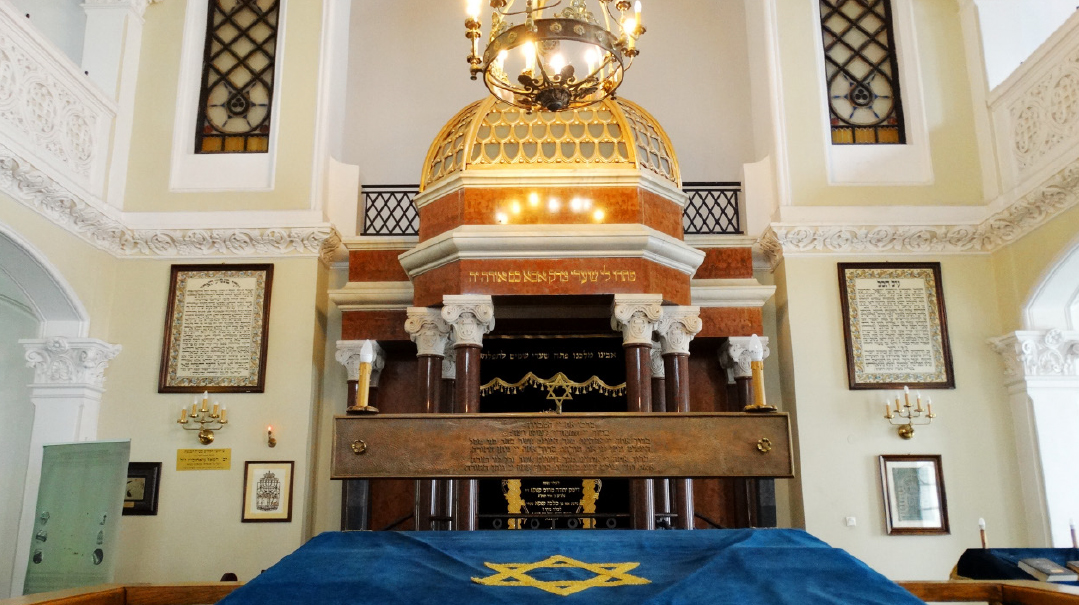

hen a gabbai walks around shul giving out kibbudim, there are a lot of details he needs to keep in mind: Are there people with chiyuvim who need to honor the memory of a departed loved one? Are there guests who need to be made to feel welcomed? Are there regulars who haven’t been tapped for a while? And perhaps most importantly, for the comfort level of both the person being approached and the kehillah as a whole: Is the person being asked to play a role in the davening actually capable of performing the task being offered?

So it was with interest and admiration that I watched the gabbai in one recent minyan. He deftly navigated the shul, finding volunteers, doling out honors, receiving rejections and thanks. Finally, he needed to give out hagba’ah. This can be a particularly challenging kibbud to assign, due to all the variables one has to consider: How heavy is the Torah? How strong is the person being asked? And are we in a parshah that favors left-handed or right-handed people?

There is also a certain technique to performing hagba’ah successfully. If the sefer Torah is at all heavy, you have to know how to pull it toward you off the bimah before tilting and lifting with your legs (never with your wrists), while simultaneously opening the scroll a bit and twisting your body so all present can focus for a moment on the written letters, all while preparing to step backward to the chair that has hopefully been arranged for you. Then you sit holding the Torah upright so it can be dressed by the one honored with gelilah.

In a word, hagba’ah can be intimidating. I have seen high-powered business executives who spend their days in incredibly pressured environments, surgeons who save lives with unparalleled precision, athletes who could sink a three-pointer or stare down a 90-mile-an-hour fastball, talmidei chachamim who can recite Shas forward and backward, and baalei tefillah who have brought crowds to tears during Ne’ilah on Yom Kippur, all turn down the chance to do hagba’ah when offered by a harried gabbai.

At this minyan, the gabbai offered hagba’ah to young man in his mid-teens. He politely declined the honor with the simple and persuasive argument, “I don’t know how.”

And then came an unforgettable moment: In response to the young man’s plea of ignorance, the gabbai smiled and simply said, “Well, if you don’t learn how to do it now, when will you learn?”

And with that, he handed the young man a tallis, saying, “Pull the Torah off the bimah a bit, tilt it upwards, and then lift with your legs, not your wrists….”

A couple of moments later, as this young man stepped backward and settled into the chair waiting for him, he beamed with pride. As did his father. As did the gabbai.

To understand why this moment was important, let’s consider how it could have gone differently. The gabbai, in a rush to fill all the slots and get back to his own davening, could have simply moved on to another person. The young man might have felt relief at avoiding a pressure-filled public moment that required skills he didn’t think he had. He might have felt badly about not being able to do something that others seem to do with ease. Or he might have moved on and thought nothing further of it.

Or — and this is the important part — the gabbai could have tried to encourage him the way I often see well-intentioned people speaking to their children: To push the lad to do something that was really within his abilities, the gabbai could have belittled his fears (“It’s easy”), or even worse, belittled the teen himself (“Don’t be such a wimp”). After the fact, the gabbai could have diminished the young man’s accomplishment with a derisive but well-meaning comment like, “See, that wasn’t so hard, was it?” instead of expressing pride in his overcoming his fears.

The truth is, emotions are real. If someone, especially a young person, expresses concern about something, we need to recognize that all feelings are true. As psychologists are apt to say, feelings are not good or bad or right or wrong; feelings just are. You can’t really tell someone not to be afraid of something he finds scary, or not to be nervous about something that he finds anxiety-provoking. And if the person does overcome his fear or face his anxiety, we shouldn’t belittle his accomplishment with an offhand, “That wasn’t so bad, was it?” or, “You see? You had nothing to be nervous about.”

Yes, we should encourage our kids to try new things and test their limits. But encouragement without support is just pushing them toward something that is often truly challenging for them, either physically or emotionally, or both. When people get urged to do something their brain is telling them is dangerous, they usually push back, even if that pushback isn’t apparent at first.

Too often, I see parents and teachers “pushing” those in their care instead of supporting them. Sometimes a push does indeed help a child get over his fear and lead to greater independence. More often, though, this pushing (which I define as encouragement without support) leads kids to do things once and then, regardless of how well or poorly they performed, never again. Like the boy who leins for his bar mitzvah, and despite all the mazel tovs and yasher koachs, vows never to put himself through such a harrowing experience again. Or the girl who sweats through her line in the play and, regardless of the “great jobs” and other accolades, chooses to sit out any further opportunities to perform publicly.

When this gabbai said to this teen, “Well, if you don’t learn how to do it know, when will you learn?” he was offering encouragement. When he handed him the tallis and began to teach the boy what he needed to know, he was extending support. And when he beamed with shared pride in the young man’s accomplishment, he was sending a message: I have your back, you are not alone, I know you can do it, and I’m here to make sure you know it too. So believe in yourself as I believe in you.

That young man changed during that davening. Certainly, he changed from someone who has to say no when offered hagba’ah to someone who can say yes. But hopefully, there was a greater change as well. Hopefully, he changed from a person who doesn’t need to say “I don’t know how” into one who can say “I don’t know how — can you teach me?” Hopefully, by not having his concerns belittled with unsupported encouragement and his accomplishment lessened by an undermining praise, he became a young man more confident not only in his own abilities but also in the willingness of others to support him as he tests his limits and learns more about himself and his potential.

And if we, as parents or teachers, aunts or uncles, gabbaim or neighbors, can learn to offer encouragement in a way that lifts our children up, then the lessons of this moment will continue to have an impact both on us and on the ones who need our support to help them grow.

Stephen Glicksman PhD is a licensed developmental psychologist. He serves as director of clinical innovation at Makor Care and Services Network as well as director of its research and education branch, the Makor Institute.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 987)

Oops! We could not locate your form.