Time Frame

Rabbi Shimon Yosef Meller rescues a rare photo of the Brisker Rav from a forgotten archive

Photos: Chananya Knobel, Mishpacha archives

The Judaica enthusiast in the small Eastern European town greeted his guest from Jerusalem and the pair got down to business straight away.

On one side of the table, the host — a local with an interest in the Jewish history of the Belarus-Lithuania region — spread out a mix of photos and documents for sale. As an amateur, he couldn’t identify many of them, but he’d told his guest over the phone that the artifacts were a century old.

That assurance had been enough to persuade Rabbi Shimon Yosef Meller to get on a plane. The biographer of the Brisk dynasty, who’d spent unparalleled time in the company of the Brisker Rav’s sons and close talmidim, was in the market for something big: an unseen treasure involving Rav Chaim Soloveitchik or his son, Rav Yitzchok Zev.

The process of sorting through the file began. A miscellany of the Jewish history of the region spilled out on the table, including documents, letters and photographs. The remnants of this fabled heartland of Torah life proved interesting, but ordinary.

After a few minutes, though, Rabbi Meller struck gold.

“He handed me this photo, and I couldn’t believe what I was holding. There, stamped with the seal of the Warsaw district authorities, was the marriage certificate of the Brisker Rav. And looking out from the document was a breathtakingly-clear picture of the Rav, the earliest known in existence.”

As an experienced bargainer, the visitor swallowed his sense of wonder and continued flipping through the collection as if the photo was unremarkable.

In the end, he selected a number of items at a low price and walked away — feeling like he’d picked up the crown jewels at a yard sale.

Back in his Rechov Sorotzkin apartment in Jerusalem — a photographic shrine to generations of the Soloveitchik dynasty — Rabbi Meller takes stock of his find, about whose origin he’s deliberately coy.

It centers on a period from which relatively little is known about the future legend. We know that he was married in Warsaw in Shevat 1910, and that the event was a major event in the rabbinic world, as befits the son of one of the generation’s gedolim.

We know that Rav Yitzchok Zev’s wife, Alta Hendel née Auerbach was a granddaughter of Rav Meir Auerbach, one of the leading rabbanim of Yerushalayim, known by his halachic work Imrei Binah. We know also that “Reb Velvel,” as the Brisker Rav was known, continued developing his Torah greatness in his father’s shadow, even after marriage.

But besides the mesorah of stories guarded by the Brisker Rav’s sons about their father’s early years, there’d been no photographic record of that period.

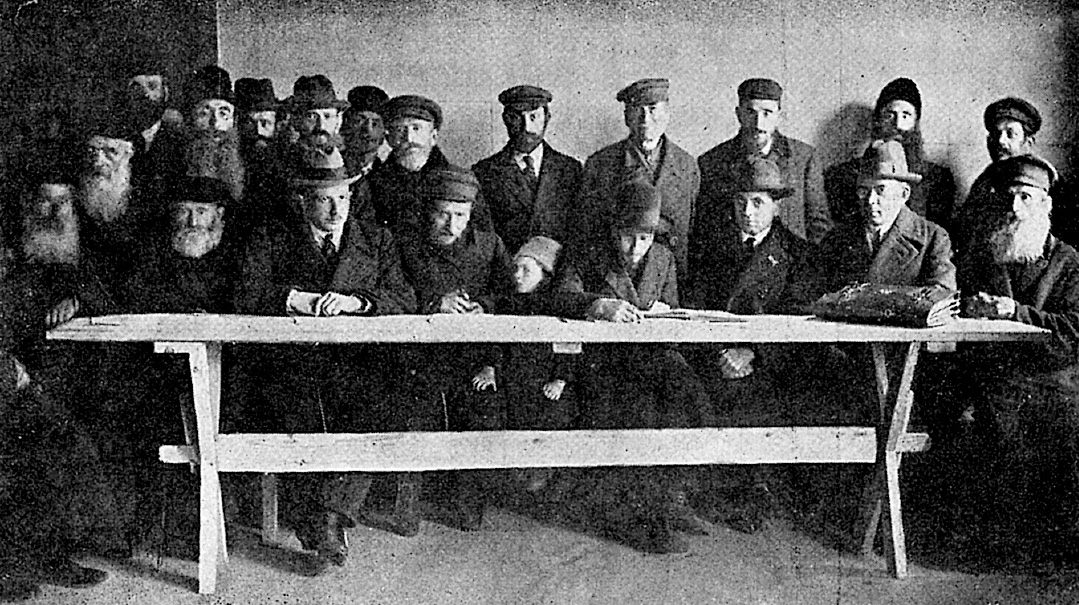

Until now, the earliest image was a grainy picture of the Rav from more than a decade later in 1921, when as his father’s rabbinical successor he attended a meeting of the town leadership, which was attempting to regroup after the devastation of World War I.

The grandchildren of the Brisker Rav were also moved to see the other half of the marriage certificate, which contains a picture of their grandmother, who lost her life along with many members of the family in the Holocaust.

“These images are the equivalent of the footage of the Chofetz Chaim that emerged a few years ago, which caused a sensation across the Torah world,” Rabbi Meller says. “I got the same shiver when I saw them.”

Whether that comparison is borne out remains to be seen, but the very fact that it can be drawn at all testifies to the unique stature — indeed, mystique — that Brisk enjoys in the contemporary Torah world.

Rabbi Shimon Yosef Meller “I got the same shiver as when I saw the rare footage of the Chofetz Chaim”

Early Greatness

The long-forgotten Warsaw photographer who snapped the image of the young Rav Yitzchok Zev obviously knew his job. It’s no mere photograph, but a portrait — a character study with depth.

The primitive lens captures a mixture of power and reserve, a commanding personality with a soft edge.

“What fascinates people is that the characteristics that we associate with the Brisker Rav — persistence and authority mixed with a softness — are already present at that young age, 24 years old,” says Rabbi Meller.

“When I showed the picture to Rav Baruch Mordechai Ezrachi, he commented that the yiras Shamayim that was the Rav’s trademark was written all over his face.”

That rounded personality was a direct result of his parents’ education. Born in 1887 as Rav Chaim Soloveitchik’s third son, little Velvel (known to posterity as either “Reb Velvel” or the “Brisker Rav”) was the third link in a family chain that was tied to the town of Brisk.

His grandfather, Rav Yosef Dov HaLevi Soloveitchik, known by the name of his work Beis HaLevi, was appointed rabbi of the town in 1877, when the previous incumbent, the Maharil Diskin, moved to Jerusalem.

His marriage to a granddaughter of Rav Chaim Volozhiner — founder of the legendary Volozhin yeshivah — put the Beis HaLevi at the heart of the Eastern European Torah world. His son, Rav Chaim Soloveitchik, known as Rav Chaim Brisker, continued that connection to the legendary institution, when he married Lifsha, the daughter of Volozhin rosh yeshivah Rav Refoel Shapira.

When Velvel was born, Rav Chaim’s star shone as a maggid shiur in his father-in-law’s yeshivah, and so the young family — including two older brothers and an older sister — lived downstairs in a basement still visible today. That’s how Velvel spent his first five years literally in the shadow of Volozhin.

From a very young age, Rav Chaim and his wife prepared their son for greatness — which, as the following story makes clear, was in the literal, unclichéd sense.

When Velvel was about six or seven and the family had moved to Brisk, a message arrived that the grandfather, Rav Refoel Shapira, was about to visit.

Since he was due to arrive in the local train station well after midnight, the young boy was sent to bed. But he wasn’t allowed to sleep through the night.

At about three o’clock in the morning, Rav Chaim woke up his son. “It’s time to say shalom aleichem to your grandfather,” he said, “and you should also tell him a devar Torah that you learned today.”

This was to be no mere recital of Chumash or Mishnah, though. The extraordinary scene continued as the child stood in front of his grandfather and discussed the Gemara that he was learning, which necessitated referring to other sugyos.

Rav Refoel Shapira asked his grandson to fetch the Gemara in question, but his son-in-law Rav Chaim assured him that the young boy was capable of quoting from memory — all at three o’clock in the morning.

Before the new find, this was the earliest known picture of the Brisker Rav (sitting, fourth from right) taken eleven years later, in 1921

Torah of Kindness

The undercurrent of gentleness evident from parsing the 1924 photo was an integral part of what Rav Chaim Brisker taught by example.

Rav Yaakov Nayman, a distinguished rav who lived in Lawrence, New York, was born in Brisk when Rav Chaim was still alive, and was a confidant of the Brisker Rav. In a conversation with Mishpacha in 2009 to mark the Rav’s 50th yahrtzeit, he dwelled on this aspect that’s often forgotten, given the focus on Rav Chaim Soloveitchik’s Torah genius.

“Rav Chaim was not only the rav of Brisk, he was the father of Brisk,” Rav Nayman said.

“My mother raised four orphan girls in our home, providing for all their needs. One of them was dubbed ‘Esther der moid, (Esther the girl)’ to differentiate her from my mother, who was also called Esther. When she grew up, my mother found her a shidduch with a boy of good repute. The girl met him and did not find any reason not to close the shidduch, but for some reason, was still hesitant to actually take the decisive step.

“As usual, they consulted with Reb Chaim’ke, as we called him at home. When he heard the story he replied: ‘Vi der hartz zogt ir, azoi zol zi tohn (She should do what her heart tells her),’ and hinted that she should not get engaged to the boy even though it seemed to be a good shidduch.

“After a few weeks, the boy was drafted into the army and was killed at the front soon afterward.”

That caring attitude wasn’t a one-off. Towards the end of Shabbos, Rav Nayman continued, Rav Chaim would go to visit the town’s orphanage, to check up on the children.

One time, he arrived to hear one of the orphans groaning in terrible pain. He sent for a frum physician, Dr. Shereshevsky, but when the latter arrived, the darkness made examining the child difficult.

Rav Chaim ordered his son, Rav Yitzchok Zev, to immediately put on a light, despite the fact that it was close to the end of Shabbos. The latter hesitated, but Rav Chaim insisted, “Ich heis dach dir, I am instructing you to turn on the light.”

In the Brisker Rav’s eyes, chesed was an integral part of Rav Chaim’s DNA — something that by definition was transmitted to the next generations.

“Once, the Rav was told that one of his grandchildren had done something bad — not in the ordinary childish way, but unusually cruel behavior,” says Rabbi Meller.

Although someone not likely to indulge faults just because of a family connection, the Brisker Rav’s response was that the report must be untrue.

“It can’t be,” he said. “A descendant of Rav Chaim who was such a baal chesed would never do such a thing!”

The end of the story, says Rabbi Meller, is that the report indeed proved false.

Yeshivas Brisk on Rechov Press. The building sits on what was once the Brisker Rav’s home

Disappearing Dowry

Unless another dusty archive unlocks its secrets, most details of what must have been a very prominent wedding are lost to history.

Despite Rav Chaim’s regard for his son’s greatness, which he would often praise to visiting Torah personalities, the wording of the invitation contains no honorifics.

On behalf of himself and his wife Rebbetzin Lifsha, he writes of the future Brisker Rav as merely “our precious son Mar Yitzchok Zev HaLevi.”

In a special invitation addressed to his wife’s uncle Rav Chaim Berlin, son of the Netziv, the chassan’s father eleborates more — but only about the virtues of the kallah, as a granddaughter of the “Gaon and Tzaddik, Light of the Diaspora” Rav Meir Auerbach.

Besides coming from a leading rabbinic family, the kallah, Alta Hendel Auerbach, arrived with a considerable dowry. Rav Meir Auerbach himself was a wealthy man. When he immigrated to Jerusalem in 1859, he was appointed as the city’s first Ashkenazi chief rabbi, and used his personal wealth to support Torah learning in the holy but impoverished city.

To this day, his imprint is visible at weddings in Yerushalmi communities descended from the Old Yishuv, where, famously, drums take the place of regular musical instruments. This custom dates back to Rav Auerbach, who — after a cholera outbreak decimated Jerusalem — performed a sh’eilas chalom to discover the spiritual reason for the deadly plague. When the answer came back that it was due to the music played in proximity to the site of the Beis Hamikdash, he ruled that in memory of the Churban, music should no longer be played at weddings in the city.

The Imrei Binah’s son Rav Chaim was forced to flee the Holy City to evade the Ottoman draft, and passed away in Vienna, leaving behind a wife and daughter — the latter the future Brisker Rebbetzin.

The young widow Chana eventually remarried a prosperous businessman, Reb Dovid Mintz, who later joined the Auerbachs in settling a generous dowry on his step-daughter and her illustrious chassan.

Some years later, though, the Brisker Rav lost his entire fortune, in a fashion that illustrates the tzidkus evident in his marriage certificate.

One version of events has it that he rented the apartments to poor families, many of whom failed to pay the Warsaw council taxes. When the local authorities demanded that he disclose the tenants’ identities, the Rav refused to cooperate.

As he later recounted to Rabbi Shlomo Lorincz, the postwar Agudah leader, “Could I hand over Jews to the police? Of course not! That’s how I lost my possessions.”

The Brisker Rav with Rav Dovid (left) and Rav Yosef Dov (Berel), his oldest son. He was the last one in the family to see their mother before she was killed

Mother of Royalty

Looking out from the second half of the marriage certificate issued by the Warsaw authorities is the kallah, Alta Hendel Auerbach. The image is smaller than that of Rav Yitzchok Zev, something like a passport photo. She wears a fashionable, wide-brimmed dark hat — likely indicating that the picture was taken after the marriage.

Back then, that wasn’t a given, even in pedigreed circles in Lithuania where kisui rosh for married women was a challenge among the younger generation.

Shown the photograph of his grandmother, one of the Brisker Rav’s grandsons — a leading member of the large family — was moved, calling her the “mother of royalty.”

He also remarked on the unexpectedly cosmopolitan air of the young kallah — a fact that shouldn’t be surprising given that she came from a wealthy house.

Rebbetzin Alta Hendel — matriarch of the Brisker dynasty — wasn’t destined to live long. Two decades after the picture was taken, she was killed in the war along with three of her children.

It was because of the Brisker Rav’s fragile health that the family found themselves separated, with the Rebbetzin ultimately left behind in the Gehinnom on earth that was war-torn Europe.

The couple’s oldest child was Rav Yosef Dov, also known as Rav Yoshe Ber, or Rav Berel, and he was his illustrious father’s right-hand man. The Brisker Rav’s many health issues required him to spend several months each year in the resorts of southern Poland or Czechoslovakia, and it was Rav Berel who accompanied him.

The war’s outbreak found the Rav in Krenitz, a spa town in southern Poland, with Rav Berel. The two made it back to Warsaw, but were unable to return to Brisk.

The Brisker Rav managed to escape to Vilna, which for a short time — according to the terms of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact — was an independent city, sandwiched between the Nazi and Soviet empires. It provided the escape route for thousands of yeshivah students.

The Rav reached Vilna along with four of his sons: Rav Yosef Dov, Rav Chaim, Rav Raphael, and Rav Meshulam Dovid. Several months later, three more children managed to evade the Nazis’ clutches and join them: Rav Meir Soloveitchik and his two sisters, the future Rebbetzins Lifsha Feinstein and Rivka Schiff.

Following the Rav’s escape with six of his children to Eretz Yisrael in 1941, Rav Berel remained behind to assist the rest of the family in fleeing the continent.

His mother soon arrived in Vilna to obtain the visa her husband had arranged, but the visa office was closed that day. Disheartened, she returned to Brisk, but not before taking leave of her oldest son.

It was a poignant meeting; Rav Berel was to be the last surviving family member to see Rebbetzin Alta Hendel.

She and three of their children were murdered by the Nazis outside of Brisk — her recently revealed picture the first glimpse that the current generation of the family have seen of their grandmother.

Brothers Rav Dovid and Rav Meir share a personal moment. Soon the entire family, never those to seek publicity, began to support Rabbi Meller’s efforts

Telling Details

The many stories preserved in the Soloveitchik family’s collective memory aren’t random pieces of information, but a body of knowledge that is preserved by storytelling that is unique to Brisk.

“In Brisk, everything that the Rav did is a ‘maiseh,’ ” explains Rabbi Meller. “It had a reason, so it has value to preserve as a story.

“Because stories are important, the details are important as well, so they’ll tell stores and mention that ‘The sun was shining, and just then a wagon drove past’ — details that aren’t crucial for the story. The purpose is both to preserve the emes and also as an effective storytelling technique. If there’s a reason for relating the incident, it should make an impression on the listeners as well.”

The Brisker Rav himself was a noted storyteller, and one incident crystallized how he viewed the purpose of the anecdotes.

“There was a watchmaker in Brisk,” the Rav once began a story — and then halted.

“I don’t remember which watchmaker it was,” he said, and abruptly concluded, “I won’t tell that story.”

When he was asked why it mattered whether he could remember a peripheral detail, Reb Velvel replied that it was a question of the truth — the absolute emes he demanded of himself.

“If I don’t say who it was, then people who retell the story will fill in with another name, possibly the wrong one, and I don’t want a lie to come about through me.”

“Briskers are not storytellers per se,” explains Rabbi Meller. “The point is the mussar that emerges, so obviously Reb Velvel thought that there was a lesson to be learned, and yet the faint possibility of a future untruth outweighed whatever positive lesson was to be gleaned from the story.”

In Search of Truth

Decades of close association with the Brisker dynasty — notably Rav Dovid and Rav Meir, the Rav’s sons — have rubbed off on Rabbi Meller, a fact that’s obvious in his ability to transform the discovery of an old photo into an hour-long saga.

It was his mother’s petirah, when Shimon Yosef Meller was 24 years old, that triggered his quest to tell the story of Brisk.

Raised in a very different world — his father, Rav Elimelech Meller was one of the first bochurim to learn in the newly reborn Mir Yeshivah in 1940s Jerusalem — Rabbi Meller’s path to Brisk came via Chevron, in an Israeli yeshivah world whose arteries hadn’t hardened into the far-clearer divisions of today.

“Back then, a handful of bochurim would still go every year from Chevron to Brisk — something that’s unusual today — and my older brother advised me to join him there.”

Shimon Yosef was attracted by the aura of Brisk. “It was a closed world, dedicated to emes, detesting outer trappings and what they called ‘noch machen,’ or imitation, and I was drawn to something there.”

Decades later, the mystique of Brisk hasn’t dimmed. The era when American bochurim would come to Ponevezh or Chevron is long-gone — today, Brisk and its various satellite yeshivahs are the premier destination for those coming to learn in Eretz Yisrael.

The trend is so marked that a well-known Ha’aretz article memorably termed Brisk the “Haredi Harvard.”

It’s doubtful that a picture of any other great Torah leader — however rare — would be greeted the same way as a new image of the Brisker Rav. When an unclear, pirated version of Rabbi Meller’s finding appeared a few weeks ago on an Israeli web forum dedicated to Torah figures, it immediately generated a buzz.

The allure of Brisk is partly a result of the legendary personality of the Rav himself. In the postwar rebuilding of the Torah world in Israel, he was the clear leader. Through his talmid, Rav Elazar Menachem Shach, he set the tone for the chareidi response to many of the issues of the day.

Brisk’s appeal is also that it’s the bastion of the analytical, incisive approach to learning that was first propounded by Rav Chaim Soloveitchik and spread to the pre- and postwar yeshivah world through the figure of his son.

Setting his sights on learning Kodshim — the centrality of which is another thing that sets Brisk apart — Meller joined Rav Dovid Solevitchik’s yeshivah, where he remained for 13 years. Unafraid to push himself forward, the young man, then in his early 20s, did what he’d done in Chevron, his former yeshivah.

“I always try to get close to gedolim. I developed a close relationship with Rav Simcha Zissel Broide, the Chevron rosh yeshivah, and so when I came to Rav Dovid’s I tried to do the same.”

In Rav Dovid Soloveitchik, he discovered a warm, paternal figure.

“He was so caring — really like a father for the talmidim. People have the wrong impression of the Briskers, as cold, dry individuals. That couldn’t be further from the truth, at least when it comes to the gedolim that I knew. There is an outer shell of reserve — they want to know what your motives are. But once you’re in, they’re soft and caring in ways that you can’t imagine.”

Opening the Door

That kindness ultimately gifted the Torah world a wealth of biographical knowledge about the wider Brisker dynasty.

“I was broken when my mother passed away, and wanted to do something in her memory. So I plucked up the courage to ask Rav Dovid whether I could print some of his shiurim as a sefer in her memory.”

It was an audacious request. Up to then, the entire official output of Brisk consisted of the works of the dynasty’s first three generations: the Beis HaLevi, Rav Chaim Soloveitchik, and his son the Brisker Rav.

“It’s a very inward-looking world. If you wanted to learn the Torah of Brisk, you needed to go inside their beis medrash. That was true of both the sugyos and the mesorah of Brisk which would be delivered in the famous Chumash shiur, when many of the stories were told.

“Taking any of that outside the walls of Brisk by publishing was taboo — an attitude born of protectiveness for the integrity of what was being taught. They didn’t know if someone else would reproduce it exactly.”

That was the background for Rav Dovid Soloveitchik’s response when Rabbi Meller asked for permission to print his shiurim.

“Vos?” he asked in amazement.

But after giving it some thought, the Rosh Yeshivah answered in the affirmative. “He stipulated that it shouldn’t only contain the Torah of Brisk, so I added shiurim from Rav Simcha Zissel Broide, and my father, who was a great rosh yeshivah in his own right. Obviously, I knew that it was Brisk that would interest people, so I included about 70 percent of content from Rav Dovid.

“His second condition was that he go through the whole sefer — a stipulation which obviously delighted me.”

Adorned with a haskamah from his rebbi, the resulting sefer, called Shai LaTorah, proved an instant hit. It was the first time that Brisk had officially ventured out of the beis medrash.

But despite that official backing, Rabbi Meller came under attack. “The older talmidim of Brisk felt that what I had done was wrong, and they disagreed with what Rav Dovid had done. But he told me to ignore the criticism. He obviously felt that it was time for Brisk’s Torah to gain a wider audience, that there was a thirst that had to be satisfied.”

From shiurim, the next step — to which Rav Dovid proved receptive — was a compendium of Brisk’s minhag, mussar, and hashkafah, which became the large Uvdos V’Hanhagos L’Beis Brisk.

For Rabbi Meller, the memorial for his mother was well on the way to becoming his life’s work. Determined to talk to all the talmidim of the Brisker Rav, he moved his young family to Boro Park for eight months, the better to record the memories of those who’d moved to America.

By that stage, Rav Dovid Soloveitchik himself wanted to involve his family in what had become a personal project.

“He told me to go and speak to his youngest brother Rav Meir, who had initially been against the seforim. He looked eerily like their father, the Brisker Rav. I became Rav Meir’s driver for years, and that’s how I was able to write down his recollections on a daily basis, now published in diary format.”

The final stage was a leap: biographies of both Rav Chaim and the Brisker Rav, which in due course bore the imprimatur of both sons of the Rav, and went on to become bestsellers.

Rav Dovid implicitly trusted Rabbi Meller. “He’s a ne’eman, he’s reliable”

Guarding the Past

Spread out on the table in the Mellers’ Sorotzkin home are the results of that single-minded focus on recording those conversations in the form of the many seforim and books that Meller has authored.

Alongside them lie a random assortment of the manuscripts, historical documents, and Torah world Judaica that the Brisker biographer has amassed over the years.

His interests range far from Brest-Litovsk, the current name of the city where the Soleveitchiks reigned.

There is a halachic treatise from a bygone rabbi from Ohio; a condolence letter from the Bobover Rebbe to Agudah MK Rabbi Menachem Porush; brown leather-bound, gold-tooled chiddushim from prewar roshei yeshivah.

And of course, a rare find from Brisk — an early manuscript from Rav Chaim Soloveitchik’s Chiddushei HaGrach that the author ultimately rejected.

It’s the yeshivah equivalent of a bank vault, and it’s the result of a decades-long obsession with recovering the past of the Torah world that was violently destroyed.

The photo of the Brisker Rav emerged as the result of an extensive web of contacts in the international Judaica market and with experts and collectors in Poland, Lithuania, and Belarus.

Scouring the gray zone that is the area’s Jewish antiquity market takes up vast amounts of time, and there’s an element of cloak-and-dagger to the whole process, says Meller. Besides not wanting to inflate the price, the market for historical objects in Eastern Europe is not clearly regulated.

That has meant that discreet, face-to-face meetings are the best way forward. Most of the time, those encounters don’t yield much — and every so often, there’s a breakthrough moment.

“I put a lot of effort now into photos, because our generation wants to connect to gedolim by learning about their lives, in a way that previous generations didn’t feel the need to.”

One hundred twelve years after a young rabbi walked into a Warsaw photographer’s studio to provide an image for his marriage documents, that picture has come back to life, thanks to the all-consuming drive that has gripped Brisk’s biographer for the last decades.

The black-and-white picture is an amazing illustration of precocious greatness — preserved under the dust of a century for a generation which venerates the Brisker Rav. —

Trustworthy Confidant

It wasn’t a simple thing for a young Rabbi Shimon Yosef Meller, the acclaimed biographer of the Brisker dynasty, to gain the trust of the rabbanim and naturally wary extended family that made up “Beis Brisk” when he began to publish some 30 years ago.

Rabbi Meller’s first published works — the Prince of the Torah Kingdom series about Chevron Rosh Yeshivah Rav Simchah Zissel Broide (Rabbi Meller is both a Brisker and Chevron talmid) and the popular set of seforim of Brisker Torah called Shai L’Torah, and a compendium of Uvdos V’Hanhagos (Stories and Customs) m’Beis Brisk — featured the Torah, some of the family customs, and the occasional story of the Brisker dynasty. But a full-length biography of the Brisker Rav was inconceivable back when Rabbi Meller started writing. Yet as he immersed himself in the Torah, he realized that the stories and background were also a “Torah,” each anecdote or insight alive with relevance and significance. Soon, the rabbanim — including Rav Meir and Rav Dovid Soloveitchik zichronam livrachah — and the family began to actively support his efforts. And once the Soloveitchik family was behind him, veteran talmidim and even Brisk natives shared their own stories. He was given access not only to their memories, but even to family documents. The Brisker Rav: The Life and Times of Maran Hagaon HaRav Yitzchok Ze’ev Halevi Soloveitchik was his groundbreaking biography.

In this work, Rabbi Meller has managed to capture the mystique, charisma, depth, and brilliance of Brisk. Some 15 years in the making, the author — who has been known to board a plane at a moment’s notice to track down a lead, to locate a photo or document — pored over archives and old letters and then filtered all the information through the precise memories and traditions of the Brisker family; it’s a work that called for the meticulousness of a scholar, but also the reverence of a talmid.

Rabbi Meller learned in Brisk as a bochur and remained a close talmid of Reb Dovid ztz”l until his final day. For 36 years he closely accompanied Reb Dovid, helping him with whatever needed to be done and taking him where he needed to go. And over all those years of closeness and conversation, Reb Dovid shared with him crystal-clear memories of his childhood in Brisk and details of the family’s subsequent rescue during the Holocaust and arrival in Eretz Yisrael, which few today remember. Those memories formed the basis of Rabbi Meller’s Acharon Ledor Deah, about the life of Reb Dovid.

“Meller is a ne’eman, he is reliable,” Reb Dovid once said to a room full of talmidim who joined him on Purim. It was the supreme compliment in a home where few attributes are more prized than truth.

His subsequent work, Rabban shel Kol Bnei Hagolah, a biography of Rav Chaim Brisker, is a bit of a surprise, as most people associate Rav Chaim with his groundbreaking lomdus, but not necessarily his communal impact. Yet by the time he passed away at the relatively young age of 65, Rav Chaim’s name appeared on every kol korei and communal appeal to the authorities, having been held in great esteem for his communal actions from the time he was 30.

Rabbi Meller’s other titles include Hakohein Hagadol Me’echav, a 500-plus page biography about Rav Aharon Cohen, Rosh Yeshivas Knesses Yisrael-Chevron; The Torah of Brisk and Other Gedolim – Inspiration for the Days of Repentance, and De’Chazitei LeRabi Meir, based on conversations with Rav Meir Soloveitchik.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 948)

Oops! We could not locate your form.