Therapists

| May 13, 2015

As a veteran psychologist, Dr. Nosson Solomon is in the business of helping people cope with their fears and anxieties. But as he contemplates the future of his profession in the Orthodox community, he has some worries of his own.

To be sure, Solomon — a Flatbush-based former president of NEFESH, the association of Orthodox Jewish mental health professionals — has seen major and positive changes in communal attitudes over the course of his many years in practice. Forty years ago, it was the rare frum Jew who went to a psychologist.

Back then, seeing a psychotherapist carried the implicit message that the client wasn’t fully normal and evoked fears of social condemnation or harm to a family’s shidduch prospects. Practitioners were also suspect of bias against religion and of seeking to influence clients to drop “extreme” rituals. The Yitti Leibel Help Line was founded over 25 years ago for the very purpose of enabling people hesitant about therapy to speak discreetly by phone with a frum therapist.

What a difference four decades make: Today, the religious community boasts thousands of home-grown mental health professionals, including many in the chassidic orbit, and their schedules are packed with clients from every walk of life. Rabbi Binyomin Babad, director of Relief Resources, an agency that pairs therapists with clients and has offices in seven different cities both here and abroad, estimates his agency fields 200 calls daily and interacts with upwards of 1,800 clients each month. Therapy as a legitimate avenue for those in need of mental health services has truly come of age.

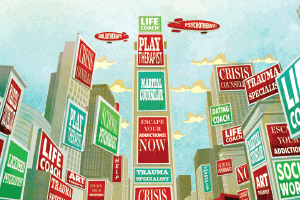

But with change comes challenge. The newfound acceptance of “going for help” has transformed the mental health field into a popular career choice for people looking to leapfrog to a livelihood, circumventing the many years of schooling that other professional careers like medicine, law, and accounting entail.

And once graduated, says Dr. Solomon, these people are accelerating their entry into private practice with alarming speed, foregoing the valuable experience they would gain were they to first spend some years providing therapy in a clinic under the supervision of more seasoned professionals.

All too often, the casualties are those very clients who bravely battle stigma and reach out for help.

On the Fast Track

“Therapy is viewed as a very quick way to earn a living,” says Dr. Solomon. “And let’s face it: People in our community like to help people — and if you can get paid for doing it, even better. You have a lot of people who feel they don’t have a lot of time, and have got a family to support, so they go get an LMHC (Licensed Mental Health Counselor) or an MSW (Master’s in Social Work) degree in two years.”

But they also don’t want to have to wait to open a private practice, so they work in a mental health clinic or agency for a year or two and say, “Okay, that’s enough,” and go out and hang out a shingle. “For many in our community that’s good enough because all they want to know is how frum the guy is,” Dr. Solomon admits. “But there are too few good therapists out there because we live in the age of on-demand everything and push-button results, so we have therapists who don’t want to wait until they have the training and experience to begin their practice.”

Nor can governmental regulation be relied on to slow the fast track. In New York State, for example, the state education department’s only requirements for calling oneself a psychotherapist are possession of a graduate degree — either an MSW (along with the LCSW certification), a medical degree, a doctorate in psychology, or the aforementioned LMHC — and a state license.

And a degree in social work or medicine — as valuable as it may be — is no guarantee that its holder has had any exposure to therapy in graduate school. Most social work programs provide only a brief introduction to psychotherapy and many types of social work have no connection at all to the therapeutic process. Only psychologists-in-training pursue years of coursework in psychotherapy, plus a clinical internship under supervision, before receiving their degree. Yet, even then, much depends on one’s specialty: Areas like industrial psychology or educational psychology, for instance, have no relation to therapeutic practice.

New York State’s regulation of the field only extends to the use of the word “therapy” and the title “psychologist.” So long as one steers clear of those terms, he can open an office and practice counseling free from governmental oversight, even if he has just a bachelor’s or even an associate degree in an unrelated field — or no degree at all.

There’s a real danger, observes Rabbi Babad, in the fact that an unlicensed counselor has no professional association or licensing board to answer to. “A licensed therapist knows there are others looking over his shoulder to make sure he has basic competence and behaves appropriately with clients,” he says. “There’s no such check on a freelancer.”

Some sectors within the frum world are especially vulnerable to problem of unlicensed and inexperienced mental health counselors. At the more insulated end of the spectrum, fewer individuals had traditionally accrued university-level professional training in these areas, leading many in those communities to seek counseling from individuals without formal training — ranging from serious, responsible askanim to harmful and even dangerous charlatans. Today though, Rabbi Babad notes happily, an increasing number of well trained, heimish professionals are available to provide quality therapeutic services.

Rabbi Babad says the difference between a seasoned professional and one starting out often is often seen in the treatment of adolescents, when the therapist has to juggle maintaining the confidence of the teen and making sure he feels safe with the right, or at least the desire, of the parents to know how the therapy is coming along. “It’s a tightrope, and the skilled therapist will know how to make both the client and the parents comfortable. But we’ve seen some young, less experienced clinicians really turn parents off to the process because they didn’t have the skills and finesse to pull it off.”

What’s Your Niche?

Compounding the problem of premature entry into private practice is the trend to plunge headlong into a specialty, attracted by the financial rewards. Dr. Barry Horowitz, an expert in trauma treatment, remembers a recent phone call from a fellow who said, “I got your name from so-and-so and I want to go into working with offenders.”

“When I asked why, he explained that ‘it’s a good niche.’ I tried to dissuade him, telling him there are other, less-complicated niches, but he said, ‘Yeah, but no one’s doing it. It’s good money.’

“After I spent 20 minutes speaking with him about the ethical dangers involved and telling him war stories from my own experience with offenders, he paused, then said, ‘How about addictions?’ I said, ‘No, you’re not getting the point. I was at OHEL for seven years before I even thought about private practice and I had fantastic supervision there. And even then, I made the transition very slowly and under supervision. And if you’re only in the field for three, four years…’ He cut me off: ‘Actually, I just graduated this winter.’ ”

Dr. Nosson Solomon says that although the tendency to seek out specialists comes from the clients themselves, they don’t always see the whole picture. “We might get a request on the NEFESH listserv from a professional saying, ‘Looking for a specialist in women who sustained a traumatic injury in adolescence from a father…’ This is problematic for several reasons. One is that often when you go to a specialist for one issue, say, anxiety, you may discover you have other issues, with, say, separation or attachments or relationships. But he doesn’t know anything about that, he just knows about his specialty, anxiety. Or he might let other problems you may have slip through his fingers undiagnosed because he doesn’t even recognize them. But people today don’t ask how much experience he has, they just want to know his specialty. When someone opens a practice and decides, ‘I’ll specialize in trauma,’ but he’s only been in business for two years and has no specialized training or experience, what he’s really saying is that his practice is limited to trauma. Unfortunately, that’s what the business of psychotherapy is about today — finding a niche.”

Under Watch

Dr. Aviva Biberfeld, a psychologist with a private practice in the Kensington section of Brooklyn, says the two most important factors in a practitioner’s qualifications are how much experience he/she has, and whether he/she is receiving supervision, meaning that the practitioner regularly discusses his cases with a more experienced therapist who can provide guidance.

“My concern,” she says, “is that people are coming out of school and jumping into private practice too early. I can’t blame them for wanting to do that. You spend lots of money for graduate school and then you’re being paid fee-for-service at $22.50 an hour. And, at least in the greater New York area, it’s hard to find jobs to get the experience you need to move on. It’s a bit of a catch-22, and I don’t know how to solve it. But the answer isn’t to jump into private practice just because you need to pay back student loans and support your family.”

To Dr. Biberfeld’s mind, supervision isn’t just a good idea — it’s essential. “Many people who first went to unlicensed therapists have ended up in my office, and although the first requirement of this profession should be ‘Do no harm,’ some of these situations have led to harm. And I’m not talking about the sensational situations where horrific things happen. I’m talking about cases in which people are in therapy because their lives are difficult, there’s a diagnosable illness, real family stress — but if a therapist is not skilled in dealing with family dynamics, the best intentions can turn out to be harmful.”

Dr. Biberfeld tells of several such cases where the fallout landed in her office. One related to a teenaged girl who was unhappy and withdrawn in school. Her teacher was convinced that she knew what was wrong and could help her student through it without professional intervention. But when the suffering teen eventually did go for professional help, it turned out she was clinically depressed and struggling with addiction issues.

In another case, a well-meaning but minimally trained counselor nearly wrecked a couple’s marriage due to her failure to understand the dynamics of the relationship. It was only once the wife developed physical symptoms, which drove her to seek professional help, that the couple was put on the road to mending their marriage.

The value of supervision lies not only in the experience-based wisdom that the supervisor can offer regarding specific cases the therapist is dealing with, but also in his ability, as an objective observer, to help the therapist realize that personal issues may be interfering with client therapy. Dr. Biberfeld believes that, ideally, a therapist should be in therapy, too, in order to become aware of his/her own psychological blind spots.

Dr. Solomon concurs. “Real therapy is an intense process and it requires that a therapist be in touch with himself and what he’s contributing to the therapeutic process, and you can’t do that without having been in therapy yourself. That’s not to say there aren’t good therapists who have never been in therapy themselves, but I believe they are the exception.”

In fact, Dr. Solomon says he’s had supervision for all the years of his own private practice. He was supervised by a mentor for 27 years, and when his mentor passed away, Dr. Solomon joined a peer group whose members provide supervision to each other.

Relief Resources’s Rabbi Babad says that his agency generally requires therapists seeking client referrals to have supervision. Since the agency is a major source of referrals for the therapeutic community, this policy has likely increased the number of practitioners who opt for supervision. “We do our homework on the therapists on our referral list,” says Rabbi Babad, “and we’ve seen the difference supervision makes. As a rule, we also only refer to clinicians who have significant experience. When a new practitioner wants to come in to be interviewed by us so he can be placed on our roster of professionals, we tell him it’s to his advantage to wait until he has some considerable experience under his belt.”

According to Rabbi Babad, there’s another attribute that’s crucial in a therapist but can’t be discerned by a prospective client, and that’s humility. When Relief interviews a therapist who’s interested in joining the organization’s database, one of the first questions is “To whom do you turn to when you’re stumped? Do you have mentors and colleagues you consult with on difficult cases?”

“We had one clinician,” recalls Rabbi Babad, “who with a straight face answered that there was never a case where he didn’t know what to do. Suffice it to say we never contacted him again. Another time, I asked a young therapist whether there are problems he felt less than qualified to treat, and his answer was, ‘If Hashem has sent me this case then I am the one to handle it.’ That’s a real warning signal.”

Coach Class

Another form of counseling that has gained tremendous popularity of late is “life coaching,” resulting in a proliferation of training programs for life coaches. No state license is required to practice life coaching and there are no uniform standards for a coach’s mission or training. For the most part, trained psychologists are circumspect about this new and trendy form of therapy.

Dr. Solomon is quite plain-spoken about the phenomenon: “Everyone in our profession knows that coaching is nothing more than cheerleading someone’s life.” It’s a person’s prerogative to go to a coach, but I don’t know what he’ll get from it that he couldn’t get from his rav or his friend or his zeide. And I’m not sure why he should pay money for that.”

Dr. Biberfeld is similarly skeptical. “People ask me, ‘Should I go to a life coach?’ and I tell them, ‘I can’t tell you yes or no, because I don’t know what they do,’” she says. “You want someone to help you organize your life and learn organizational skills? I guess that’s okay. I’m sure there are some life coaches who are ba’alei seichel and may be helpful.”

She contrasts the LMHC, which is a two-year graduate degree, with life coaching, which is a certificate program. “You know, you can get a certificate in doing makeup and you can get a certificate in life coaching. It’s not a real graduate program, neither in duration nor in the requirements for getting into the program. It feels a little like a shortcut way to be able to do something you might not be qualified for.”

But Ezra Max begs to differ. A life coach and coach trainer in Brooklyn for the past 15 years, Max concedes that if “the definition of professional is psychiatrist, psychologist, or some other degree holder, then I’m not a professional. But having practiced, maybe even pioneered, the use of coaching to work with families in crisis, I do call myself a professional and strive to follow professional values and ethics.”

Asked to describe the difference between coaching and psychotherapy, Max explains that coaching is geared toward figuring out goals and how to reach them. Therapy, on the other hand, focuses more on going backward — into the client’s experiences, often as far back as early childhood, or even deeper, into his feelings and thought processes — to figure out what is getting in the way of functional living.

Put differently, he says, therapy works on a medical model, with diagnosis and treatment, whereas coaching is not a restorative, healing process. Using an acceptance of the client’s shortcomings as a starting point, coaching can help him discover what he wants in life and how to achieve it.

But Dr. Biberfeld takes issue with the way Max portrays therapy, noting that with the current emphasis on evidence-based therapeutic approaches, it’s no longer true that most therapists emphasize going backward into the client’s past. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) are just some of the models that focus on the client’s current functioning and the skills needed to help him meet his goals. Additionally, family therapists and many marital therapists will focus on what is in front of them, not the past — unless it becomes clear that the past is interfering with the client’s current life.

But, she adds, “it’s also important to understand that as human beings, our experiences shape us, neurobiologically and emotionally, and for a therapist to try to help people move forward in their lives without having a really solid background in understanding attachment theory and the different developmental stages that make up the person in front of you, is going to be limiting at best and harmful at worst.”

Like therapy, coaching typically takes the form of a weekly session of 45–50 minutes, and the fees are comparable to those charged by therapists. But according to Max, a coach will often be more involved in the person’s life beyond the weekly session. “The typical client is in therapy once a week for 45 minutes. So who takes care of him during the remaining 167 hours every week? I don’t know, maybe his family, but maybe he doesn’t have a family — or his family is part of his problem. So to say that there’s no room for other stakeholders in that client’s life beyond the clinician — there’s another 167 hours in this person’s week in which he might need help, and no one should help him because it’s the exclusive purview of the therapist?”

Max says he’s quite aware of the pitfalls of his chosen field, but he believes those problems aren’t intrinsic to coaching. For him, the bottom line across the mental health field is the individual practitioner’s level of competence and experience. “To my dismay, anyone can call himself a coach after attending one of my three-hour training sessions. In fact, I discontinued one of my programs because I didn’t want to be liable for people who received very limited training yet presented themselves, without my knowledge, as being trained and went on to behave in ways that fell far short of my standards.”

Max admits that a lot of people who’ve figured out that coaching is “in” are using the term “coach” without even knowing what coaching is. But just as there are great clinicians doing great work and there are not-such-great clinicians doing not-such-great work, the same is true for coaches. “If I don’t have a PhD, but I have the knowledge, experience and G-d-given talent; if I didn’t spend ten years in school, but I worked side-by-side with Dr. David Pelcovitz for six years as an understudy, and have real shimush — then if I and a kid fresh out of social work school both sit down with a client, I’ll likely do better work for the client, even though he’s considered a ‘professional.’ ”

He does agree, however, that like good therapy, supervision is key. “I know a number of coaches who have spent hours upon hours with licensed professionals, or with other coaches, to review what they’re doing and learn when to refer on to therapists. I’m blessed to have relationships with some top professionals whom I can call in the middle of the day or night.”

Counsel of the Wise

What Max says he can’t understand is why the attitude of therapists toward coaches is different than their approach toward other nonprofessionals who deal with mental health, such as rabbanim. Over the years, NEFESH and other groups and individuals have tried to create training programs for rabbanim in dealing with mental health issues, but their efforts have rarely, if ever, been successful.

“If the therapeutic community’s motivations are for the public’s good,” Max says, “and I believe they are, why not reach out to coaches as you do to rabbanim, and do training with the coaches? Why exclude coaches with an implicit message of ‘You’re worthless because you didn’t do a degree’?”

His question begs a more basic one: What, in fact, do therapists believe should be the role of rabbanim and other nonprofessionals in regard to the mental health needs of the community? Seeking the counsel of the wise, whether it be a rav, a rebbi, or a rosh yeshivah, has always been a central feature of Torah society. Similarly, Jews feel a responsibility to help others in their family or community grapple with the crises they face. Have these traditional values been rendered irrelevant by the advent of psychotherapy and the widespread availability of frum therapists who practice it?

Aviva Biberfeld gives an emphatic “no.” She says she has dealt with many nonprofessionals — whether mechanchim, rabbanim, or simply the individuals to whom community members often turn for help — who, she says, “are incredibly wonderful, seeing their role as providing support and easing the road into professional help for people who need it. Many of them have brought clients in to see me. And there are mechanchos in the Bais Yaakov system who speak with me on a regular basis about situations they’re grappling with, including some whose schools pay for them to receive supervision from me. These people do a tremendous service for our community. But then there those who don’t seem to know the boundary where their helping ends and their being potentially harmful begins.”

Where does one draw the line? One clear delineation, according to Dr. Biberfeld, is when the problem is diagnosable as a clinical disorder. Whether it’s clinical anxiety or clinical depression or personality disorders or a complex family situation, those are areas in which a nonprofessional, however smart he may be, should realize he’s out of his league and refer the client to a therapist.

“Are there rabbanim who are excellent at shalom bayis counseling? Absolutely,” she says. If a couple needs, for example, to learn communication skills, rabbanim have been doing this for a lot longer than therapists have existed. “I don’t think it’s realistic or necessary that the minute a couple comes to him, a rav has to say, ‘Here, call this number.’ The question is at what point a rav should say that this needs to be discussed in a therapist’s office. It’s a little hard to delineate, but if support and chochmah don’t resolve the problem, then send it out.”

Dr. Biberfeld says she’s grateful for the role nonprofessionals play because there are many clients who would never have sought her help had there not been people holding their hand, whether a teacher who took an interest or a family member who raised the issue and brought the sufferer to her office. “But when someone believes, whether consciously or not, that he’s able to help everybody, that he’s the last address, then there’s a lot of potential for harm.”

And that, she adds, is true “whether you’re licensed or unlicensed.”

FINDING THE RIGHT FIT

With many years of experience helping individuals find professionals who are a good fit, Relief’s Rabbi Babad is well-positioned to describe what a would-be client should look for in a therapist: As when hiring any professional, don’t hesitate to ask questions in advance. Most therapists don’t have secretaries, so you’ll be speaking to them directly when you make the initial call for an appointment. Prepare ahead of time a few things you feel are important to ask, but save longer discussions about your situation for the actual therapy session. Therapists’ only commodity is their time, so they may not be willing or enthusiastic to get into long discussions before you have even become a client.

Some questions to ask are:

- Are you licensed, what type of degree do you have (e.g., LCSW, LMHC, LMFT, LPC, PhD, PsyD), and how many years have you been practicing?

- What and how much experience do you have helping people with the problems I’m having?

- What are your areas of expertise? Do you have any specialized training for treating my issue?

- What kinds of treatments do you use, and have they been proven effective for dealing with my type of problem?

- If it’s a child or adolescent, what is your communication policy with parents?

- What are your fees? Do you have a sliding-scale fee policy?

- Do you accept any insurance? Will you accept direct billing to, or payment from, my insurance company? Are you affiliated with any managed care organizations? Do you accept Medicare or Medicaid insurance?

- What is your policy of communication in between sessions?

- Do you conduct regular evaluations of progress in therapy, including discussion of treatment plans?

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 559)

Oops! We could not locate your form.