Their Story Is Our Story

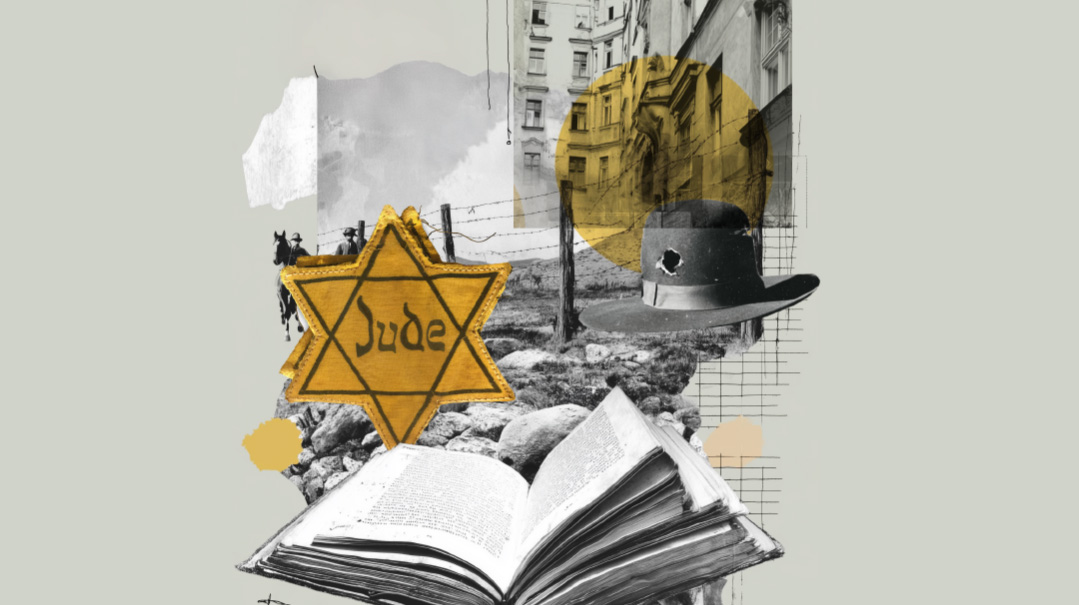

If Tishah B’Av is still a day of mourning this year, is there a Holocaust memoir that will help you tune in?

Coordinated by Michal Frischman

These days, you don’t have to look too far to find a reason to mourn the galus, and yet for most of us, connecting to the true anguish of the Churban doesn’t always come easily. While we allow the haunting tones of Eichah to penetrate, wishing we could better connect, we find ourselves turning to the voices that are closer and more relatable — those of the cherished, dwindling few who survived a churban of their own. With their words, we can, for one day, reconnect to the horror and despair of previous generations.

If Tishah B’Av is still a day of mourning this year, is there a Holocaust memoir that will help you tune in?

Pearls to Hold on to

Ariella Schiller

Title: To Vanquish the Dragon

Author: Pearl Benisch

Publisher: Feldheim Publishers

When you first read it: At age 17

Scene that hit you the hardest: When Pearl’s friend, Frydzia, is led away from the barracks.

Just as that sunrise was young and full of enthusiasm, so were we. Fighting the darkness of the world with the light of Torah.

Hoping for the great day of peace, when hate and bigotry would turn to love. Waiting for a new day to emerge from the darkness. Trusting that the awareness of G-d would embrace the entire world and wrap it in His eternal light.

(Pearl Benisch, To Vanquish the Dragon)

IT was the best of times, it was the worst of times. In other words, it was the harrowing throes of high school. Every moment, every interaction, felt so enormous, taking on giant proportions. Every interaction held meaning and weight, every day stretched to eternity, and simple things like friendships and wardrobes took center stage in my psyche.

And the drama. Ohhhhh, the drama.

And in the midst of this roller coaster of angst and identity crises and overwhelming emotions, we began to study the book To Vanquish the Dragon, by Pearl Benisch (Feldheim Publishers).

I knew about the Holocaust, I devoured books for breakfast, and as an old soul surrounded by adults, I overheard snatches and figments and anecdotes and pieced together the truth about The War. But I’d never sat at a desk, while someone taught me, as an equal Jewish adult, about the genocide of our people.

And there I was, 17 years old in Bais Yaakov, eyes wide, heart open, as Morah Flam walked us through the harrowing journey of teenage Pearl and her friends and teachers from the Bais Yaakov in Krakow. We learned it together, chapter by chapter. And it was a lot. But having it given over in the safety of a classroom, surrounded by friends, made experiencing Pearl’s story a rite of passage.

And in true teenage fashion, I realized that I had never connected to anything in my life quite like I connected to the young blonde talmidah of Sarah Schenirer. Stories of the Holocaust and war had always seemed so foreign. It was them, taking place over there, and sensitive soul that I am, I could cry, I could feel their pain, but it was never mine.

Through the lens of Pearl’s trials and tribulations, I began to understand. There was no her and me, no then and now. It was all one circle of existing, resilience, and emunah.

My notebooks full of angst-filled poems stilled as I read her poems on experiences no youth should have ever had to pen:

No angel came the sword to stop

No tangled ram was found to swap

The thousands of humans bound atop the pyre

Ready to go up

In fire

I began to view my own life differently. And I made changes. Big changes, life-altering ones. I began to grow on a trajectory that I view until today as a gift from Hashem. It was like He lifted me and helped me be the best version of myself, when maybe I didn’t possess the necessary tools to do so. I lost friendships, those scared or annoyed by my sudden growth, but I gained insights, made new friends, and on one bright winter day, Mrs. Pearl Benisch herself, author of To Vanquish the Dragon and Carry Me in Your Heart, came to Bais Yaakov to speak to us.

Sitting in the auditorium, watching the tiny, elegant blonde woman walk up to the podium, I knew something was about to happen. Something concrete was going to change.

She looked around at us, with genuine emotion and overwhelm.

“After the war, Bais Yaakov was a desert,” she said in her elegantly accented English. “We were girls without parents, without leaders. So wherever we ended up, we started a Bais Yaakov. And look at you today. Look what I am zocheh to witness.”

She stopped, overcome with emotion at the scene of one hundred Bais Yaakov girls looking back up at her.

And that’s when all the dots at long last connected. The Bais Yaakov movement Frau Schenirer had started with a small group of earnest talmidos, the efforts of pure evil to eradicate it all, the audacity of weakened, starving young girls to dare to rebuild it all from scratch… it all led up to me.

To this moment. Here. today. In my uniform, in the new millennia. It all led to this.

And when we gathered in the center of the room, joined hands, and sang the same tune Sarah Schenirer sang with her students

V’taher libeinu… l’avdecha b’emes…..

I knew, right then, it would be a moment I would forever carry in my heart.

The Silent Scream

Bassi Gruen

Title: I Promise You

Author: Yael Mermelstein

Publisher:Israel Bookshop

When you first read it: 2016, the year it was published

Scene that hit you the hardest: The one in which the Nazis told mothers that they could come get food for their babies. The narrator’s mother eagerly hurries to the spot, desperate to feed her starving infant — and instead being given food, she’s brutally beaten. I will never forget that scene.

Holocaust memoirs first began appearing when I was in my teens. Until then, the survivors had been trying to bury their memories, focused on rebuilding new lives in a new world.

As they entered the sunset of their lives, though, many of them felt the need to tell their stories, to bear witness to the atrocities they’d experienced.

I was a voracious reader, and there was a severe dearth of frum literature back then. I read every Jewish book I could get my hands on — including all the Holocaust memoirs. Curled up on the brown couch in our living room, I’d shudder at the descriptions, my mind roiling at the depravity men could fall to, while marveling at the faith Jews clung to.

While I read these memoirs throughout the year, on Tishah B’Av, I always made sure I had one. There were the classics — To Vanquish the Dragon, The Scent of Snowflowers, and Go, My Son — which I read again and again. There were the Holocaust Diaries series from CIS and the To Save a World set.

I read them all.

And on those days when I was dehydrated and hungry, reality would blur. I’d feel myself back there: in the airless train cars; waiting in line before the devil with white gloves, my fate about to be decided; lying on the wooden slats of the barracks.

It was terrifying. But with the raw optimism of youth, I told myself I would have survived. That I would have made it through, despite the odds.

Then, I got married. Had my first child. During the Nine Days, I dutifully borrowed a Holocaust memoir, and on Tishah B’Av, I began reading it.

It was an entirely different experience.

As my imagination yanked me back through the decades, I was no longer a young, strong teen. I was a mother with a baby. A baby who, in that world, would have been slated for certain death. Who would have been sent left, along with me, our lives snuffed out in an instant.

My body responded violently. That Tishah B’Av night, and for a full week afterward, I was plagued by horrible nightmares. I’d wake up sweating and choking, sure I was being chased by a diabolical Nazi. I’d grope for the infant sleeping beside me, terror coursing through my veins.

After another year of this, I became more selective. I chose memoirs that were less brutal — stories set in Siberia, accounts of people in hiding. Still harrowing, but less likely to trigger a week of sleepless nights.

Then, in 2016, my good friend Yael Mermelstein gave me a copy of her recently published I Promise You. It was the story of her grandmother’s survival.

Written in verse, it carried the cadence of poetry, and told of a coddled, deeply loved child whose world went from shimmering color to black.

Yael captured the voice of a child whose life was utterly demolished with devastating accuracy. The spare vocabulary and the stark, choppy lines hit hard.

That Tishah B’Av, I read and read. By mid-afternoon, when my stomach was cramping from hunger — a hunger that seemed laughable as I read about weeks, months, years of starvation — when I was empty and aching, I finished the book. Pieces of it lodged inside me.

The next year, I read it again, and those pieces burrowed deeper.

The image that stuck most from that horribly beautiful and beautifully horrible book was of Maniusia’s emaciated baby brother. Born into gehinnom, to a starving mother who could never procure enough food for him, the baby never cried. He was too weak to do what every baby does naturally, unable to even give voice to his desperate hunger.

That image of a silent, starving baby haunted me.

And then came the black Simchas Torah when our nation experienced grisly murders the likes of which we had deluded ourselves into believing could never happen again.

We were at war, and around us, a world gone mad. Death, so much death, and hostages locked in tunnels, abused and starved.

When Tishah B’Av came around, my eyes were dry.

There had been other years when I didn’t cry — too distracted, too overwhelmed, too numbed by life to touch the pain of galus.

And there were years when I did cry.

But this was different. This time, the pain was so vast, so consuming, it left me shell-shocked and shattered, too drained for the luxury of tears.

When I hear of yet another stabbing, when I see yet another image of a smiling boy who will never smile again, when I think of the travesties and atrocities so many have faced, I feel, for a moment, like that starving infant, too broken to even cry.

There are no tears, no words, just a silent scream of desperation, a scream that echoes through the ages, that has traveled across the continents and through time.

It is the scream of the Jew in galus. The desperate plea of a battered child waiting, still waiting, for her Father to finally bring her home.

A Flickering Flame

Rachel Newton

Title: Go, My Son

Author: Chaim Shapiro

Publisher: Feldheim Publishers

When you first read it: Age 10

Scene that hit you the hardest: When the Germans start bombing Lomza at the beginning of the war

ON

September 1, 1939, Chaim and his family are jammed into a shelter, listening as their hometown is systematically destroyed by wave after wave of German bombers. They argue about leaving — his father is certain that five floors collapsing on them would be far worse than taking shelter elsewhere, but then two bombs land in the courtyard, and the heat and shrapnel from the explosions cut his argument short. They wait as the concrete under their feet shudders, until silence reigns.

Chaim’s brother Nosson is the last in, the first out. Everyone is pushing from behind, desperate to leave, and so he runs ahead just as a bomb lands.

I read and read, the words trembling behind a sheen of tears. Chaim and his family scream, run for doctors, pray, plead.

Nosson was a kid, my age. “Will I never have a bar mitzvah?” he cries. And Papa comes back with bullet holes in his hat, but no doctor. Who would leave the safety of their home at a time like this?

Chaim holds Nosson’s hand as they all watch his life seep out of him, a life that will never be lived, a life among so many millions lost.

This life I cried for so many times. I read it now again and tear up as if it’s my first time, and wonder: Why did this scene, this death touch me more than the many other deaths I ever read about?

As a ten-year-old, I often thought about hats. Specifically, hats with bullet holes in them, atop a face drained with color. I’d see my father’s hat and my mind would take me straight to that war scene in Lomza.

Go, my son, I’d think to myself. Go! Run from the strafing, from the planes flying so low you can see the pilot’s faces… go!

While I don’t remember from which of my aunts I borrowed Chaim Shapiro’s war memoir, I’m absolutely certain my parents had no idea I was reading such a terrifying book.

I ran with Chaim for chapters and chapters, across continents, into different armies. Starvation and bullets; death-defying scenes and miraculous escapades climbed off each page and lodged themselves firmly into my psyche. I gulped and shivered and cried and continued reading.

And when I finished the book, I turned to page one and started again. The bombing scene was a scab I picked at, watched bleed, waited to harden, and picked at again.

Why did Chaim’s odyssey touch me so deeply, never lose its pull on me, no matter how many times I read it?

Maybe it was the age. My grandfather was that old when war broke out. He was also Polish. Like Chaim, he crawled out of that churban with nothing and no one. Unlike Chaim, he could never share his experiences and took them with him to world where nothing is hidden.

Perhaps my ten-year-old imagination superimposed my zeidy onto Chaim Shapiro and felt his story as if it were my legacy? Leaving Nosson’s body behind as they had to flee — did Zeidy ever see something like that? Did his nightmares contain all the siblings he lost?

Chaim survives. The older I got, the more questions I had — for what could a ten-year-old understand? How did Chaim keep his faith? How did he remember kashrus, Shabbos? How did those words, Go, my son, carry him through all of that, all the way to the war’s end?

My childhood obsession with the Holocaust never faded as I grew, though the books became more difficult to read as I became a mother, as black-and-white pictures of children made me think of their mothers. How, Chaim’s mother, did you give your son that iron backbone that would not yield?

I hesitate before giving the book to my daughter to read. It’s an awful book — do I want my nightmares to become hers? But the legacy. If we don’t read, who will? She never knew Zeidy… but will she read about the son who survived, alone, and wonder about someone I still remember? Maybe she’ll think about the responsibility we bear, to live our lives instead of those who never had the chance.

She’s fifteen. I give her the book.

My son grows older. He carries Zeidy’s name.

I can’t read the book any more; prefer to let the scab become a scar. It’s not possible for a child to survive that… no. It does not bear thinking of.

But Tishah B’Av comes, again. Despite our hopes.

And I sit on a stool and read. I think about legacies and children, about monsters who tried to extinguish the embers of a nation that will never die.

I cry as little Nosson’s life goes out, and cry as I think of the Jewish children through millennia, burned on the Molech of an endless hatred.

I cry to think of those who staggered forth and built anew so that we could live and believe.

How, Zeidy, did you pick yourself up and carry the flame that flickered on a wick’s end?

Not So Simple

Shmuel Botnick

Title: Berbesti to Burncrest

Author: Shloime Yunger

Publisher: (Never published)

When you first read it: Shortly after my engagement

Scene that hit you the hardest: The train stop on the way to Auschwitz

“B

erbesti” is pronounced “Berbesht.”

If you knew Shloime Yunger, you knew that too.

I remember Shloime as an elderly Holocaust survivor, one of the many who found a home and solace in Toronto’s Jewish community. To an uncomprehending child like me, little of his profile revealed a plagued past. His walk, perhaps. I remember him leaning on his children or grandchildren for support as his tall, frail legs struggled to carry him.

He liked schmaltz herring and Crown Royal. He had a fantastic sense of humor. And as anyone who spent any time with him can attest, he was from Berbesti.

Shloime Yunger always spoke about his upbringing in Berbesti, a small town in Romania, as a shining utopia.

“In Berbesti, we didn’t throw out leftovers. We ate it for supper the next day!”

“In Berbesti, the children cleaned the house for Shabbos, not a goyishe cleaning lady!”

“In Berbesti, we didn’t have parties on Chanukah, we played kvitlach!”

He was jeweler by trade, and here’s where Torontonians learned the Golden Rule of Life: Don’t try to finagle a deal out of a Berbester. You’ll never win.

I remember being saddened when, in 2010, I learned that Shloime Yunger had passed away. And when, in 2013, I was redt to one of Shloime Yunger’s granddaughters, the first thing my father said was, “Ah, Berbesti!”

When we announced our engagement, I couldn’t count how many Berbesti comments I got. Then my future mother-in-law handed me her father’s memoirs, titled Berbesti to Burncrest (Burncrest being the street he lived on for most of his life).

I had finally made it. I too would count among the prized Berbesters.

Shloime — now Zeidy — wrote these memoirs over the course of several years, and the family made a conscious decision to preserve his exact wording rather than lend it some polish and flair.

It was the right decision. The charm explodes from the opening line of the acknowledgments:

I would like to thank my wife Lilly for helping me with spelling and some suggestions, even though she is not a Berbester. (It is not simple to be a Berbester.)

Zeidy possessed neither a degree in English nor a command of the language, but Dickens and Hemingway could step aside. There was an authenticity here that can’t be matched.

I anticipated a most enjoyable read, replete with delicious tongue-in-cheek humor and old-style Yiddishisms. Zeidy did not disappoint.

We also had a rosh hakahal whose name was Moshe Shmuel. Of course, the richest man, and automatically the smartest man (supposedly), was picked. But that was not necessarily true. He could be rich, but not smart! But there was nothing anyone could do about it. By today’s standards, he was not rich at all. I think people here on welfare live better than our rich rosh hakahal… If somebody needed an eitzah, they went to him, whether he gave you good advice or not.

He shares a story about a prank played on a married couple of compromised mental capacity:

On the night of the first Seder, when basically everyone was finished their Seder, the older bochurim decided to have some fun. They took a goat and wrapped a tallis around it. When the newly married couple opened the door for Eliyahu Hanavi, in walked the goat with the tallis over its head, blinding it. It jumped from the table, onto the bed — all over the small room. Of course, the couple could not touch it, because to them it was Eliyahu Hanavi, and they were very happy that he came! Finally the goat left the room. You can imagine what a mess it left behind!

One short, typical aside:

One family in Berbesti were called shaidim, I don’t know why. They were, and are, nice people.

To be fair, the book is far from a collection charming vignettes. For the most part, it is detailed history, and it’s astonishing how much Zeidy remembered, so many years after it happened.

The stories, anecdotes, and memories run for an informative, humor-laced six chapters. Then comes Chapter 7, titled simply: “World War II Begins.”

The opening sentence is: “At the beginning of 1944, dark clouds began to descend upon us.”

Then Zeidy describes the beginning of the end.

Though our lives were primitive and poverty-stricken, we lived happily. Fairly everybody was content, until Pesach 1944. It was the middle of the first Seder. A larger table was set up in our home. It was covered with a white tablecloth and the best keilim and glassware we could muster. Suddenly we heard the sound of roaring trucks.

My sister Aidel looked out of the window and shouted, “German soldiers are descending from the trucks!”

We took apart the beautifully set table and hid the food from the stove. I do not remember what we did with the candles. We sat and hoped for the best. Al pi neis, the soldiers did not come into our house.

From then on, Zeidy describes in painstaking detail the events that followed. A proclamation went out that all Jews were to gather in the shul. Some 500 Jews — Zeidy’s family included — escaped into a nearby forest. About two days later, a Hungarian general came to their hideout and announced that all Jews were welcome back to Berbesti and all their belongings would be returned to them.

The fugitives were all too happy to return home. But they soon realized this was a trick. The Hungarian general had been working on behalf of the Nazis and deceived the Jews to return home. And so it began. The yellow stars, the curfew, the back-breaking labor.

And then came deportation. Zeidy describes the screams, the cries, the wicked laughter, and the specially designed sticks wielded by Hungarian civilians. The terrorized Jews marched to Sighet. Chapter 7 ends there.

Then comes Chapter 8: “Our Journey to Auschwitz.” It is difficult to read. Zeidy describes the railway cars, jammed to impossible capacity. The wretched stench, a small but growing pile of deceased heaped in a corner. He describes the arrival in Poland, where the train pulls to a stop in a “crazy, smelly place.” Babies being snatched from mothers’ hands and tossed onto trucks, Germans calling to their starving dogs, “Mensch, iss den Hund! Person, eat the dog!”

Chapter 9 is titled “Auschwitz.” It begins:

The morning we arrived, those who went to the left were gassed and burned within the next few hours. For us, the “lucky” ones, the tzaros had just begun. We were jealous of the ones who were gassed and burned! Many times, we wished we were dead.

Zeidy describes how they were shaved of all their hair, and, after hours of waiting, were given pants, a jacket, and a head cap (muze). He writes that they thought these were pajamas. “Somebody quietly asked for his clothes. He got a punch and a bloody nose and was told, ‘These are your clothes.’ ”

Interestingly, “Auschwitz” is a short chapter. Zeidy shares how, one day, the Nazis announced that they needed strong young people in a different camp, and anyone who wanted to go should step aside. Most of the Berbesters and those from surrounding villages stepped aside. Zeidy explains that since they had a more difficult upbringing, they were in better shape than those from the wealthier Hungarian cities.

The Nazis gave those who stepped aside a stack of heavy stones and instructed them to run back and forth. Those who did so were selected to be sent away. The story continues with Chapter 10, “The New Camp and March.” Strangely, Zeidy never reveals the name of this “new camp.” He simply calls it “the camp.”

The camp we arrived in was relatively small. We found there about 1,200 to 1,500 Polish Jews, mostly Muselmanner. And a Muselmann is a person who has sunken eyes and is very skinny. He will eat anything, garbage, rotten food, grass, mice, or even rats.

Within a few days or weeks, he or she will die of malnutrition anyway.

We arrived on the second day of Shavuos. We got good soup made out of peas. The camp eldest said to the other Polish prisoners, “These are strong and healthy people, not like you.”

The other prisoners said to us that within a few months we would look like them.

Unfortunately, they were right.

Zeidy was assigned to a job mixing cement. He worked 12 hours a day with a half-hour break for lunch, which was “two thin slices of bread and a bit of margarine.” Apparently, he didn’t have it the worst: “When I told my friends how hard my work was, they said it was Gan Eden compared to the work they did — carrying heavy steel railway tracks.”

Following work, they had to march two kilometers back to camp. The Nazis made them sing as they marched. “I do not understand why we had to do this.” When they returned to the camp, at around 9 or 10 p.m., they were given “soup,” always in quotation marks, and loaves of bread, to be divided among groups of four.

As the war stretched toward its final close, the Nazis ordered everyone healthy enough to march. They marched for eight weeks. One day, the Nazis ordered wagons, upon which they loaded about 200 marchers who no longer had strength. They then requested volunteers for “special work,” promising them a loaf of bread in return.

There were hundreds of people who wanted the job! Later we found out from one of the guards that the volunteers dug one big grave and all of the people were thrown into the grave, some of them still alive. The volunteers were shot and thrown into the grave too so that they would not be able to tell anyone what happened.

Finally, they arrive at their destination: Buchenwald. It was April 1945.

The whole camp was in chaos. However, the SS were still in control. Each day they shipped 10,000 to 12,000 people out of the camp to go on death marches. Very few people survived these marches. Weather conditions were still bad and there was very little food. We found out from those who survived that they were eating grass and green leaves, and even that had to be done illegally. If one of the SS guards caught you doing it, they shot you immediately.

And then, after all the unfathomable suffering, everything changed.

On April 11, 1945, Zeidy and his fellow prisoners were given a sudden order to return to their block and lie on their stomachs. They did so, not understanding the reason for the fierce rounds of incessant gunfire. Some two hours later, one of the prisoners dared lift himself up and reported that he saw soldiers in different uniforms, throwing chocolate, candy, and pieces of bread.

We started crawling out of our blocks. Our only fear was that the Germans would return. The Americans assured us that they would not. The Americans were furious at what they saw: half-burned bodies, walking skeletons in dirty pajamas, crazy people walking around in a daze.

And just like that, the nightmare was over.

Zeidy may have been a free man, but he was still in mortal danger. In Chapter 12, “Davos,” he describes how he was 70 pounds at the time of liberation and was transported to a hospital in Weimar in terrible medical condition.

One day, an American chaplain named Schechter paid him a visit. In Yiddish, he said, “You must not die! I want to help you with whatever you want.”

He then produced half an orange and squeezed it into Zeidy’s mouth. This chaplain continued visiting Zeidy and providing him food. After about four weeks, the color began returning to Zeidy’s face.

This chaplain informed Zeidy that a transport of about 300 young men was traveling to Switzerland. Most of the men had tuberculosis — as did Zeidy — and the fresh mountain air of Switzerland would be healing for them. The chaplain encouraged Zeidy to join, which he did.

Most of the transportees were placed in a sanatorium in Davos. Zeidy describes their broken spirits, with many saying they no longer wanted to be religious. But a Gerrer chassid named Reb Refuel Horowitz from Krakow made it his business to mend these shattered souls.

Reb Refuel had come to Davos before the war to recover from tuberculosis. When the war broke out, he wrote to the Gerrer Rebbe, asking if he should remain in Davos or return to his wife and two children. The Rebbe instructed him to remain. Zeidy describes Reb Refuel as a true tzaddik, who gave up everything for others. Slowly but surely, everyone within Reb Refuel’s presence drew closer to Yiddishkeit.

Zeidy traveled to Paris and managed to procure a visa to Canada. He left for Montreal, where he found work fixing typewriters, somehow managing to avoid working on Shabbos. But when winter came, Zeidy left work early on Friday. This, the employer would not tolerate.

Zeidy got a letter from a dear friend of his from Switzerland, Manny Hendler, who had settled in Toronto. He invited Zeidy to join him, which he did. Zeidy got another job at a typewriter company, making an impressive $42 a week. Things seemed to be moving in the right direction.

But then, in 1952, a routine check-up revealed that Zeidy was having lung problems. He was sent to a sanatorium in Hamilton, Ontario, where the air was cleaner.

While in the sanatorium, Zeidy learned of a Jewish Hungarian girl named Lilly Reicher, recovering from tuberculosis in the women’s section. Zeidy snuck out of his building and went to visit her. After he was discharged, he continued to travel to Hamilton to pay her visits. Eventually she was discharged and moved into a home in Toronto. Zeidy began visiting her almost every night.

Finally I proposed to her, and luckily, she accepted. We set a date for our chasunah, and I gave her an engagement present: combs, a mirror, and brushes — no diamond ring!

While Zeidy passed away before I joined the family, Bubby did not. She lived for about one year after our wedding, just enough time for me to miss her dearly. It would take writing skills the likes of which only Zeidy possessed to describe what a wonderful person she was. Bubby Yunger saw joy in everything, and cherished the blessing of life more than anything else in the world. She loved people, and, on a summer Shabbos afternoon, would just sit outside, smiling and wishing good Shabbos to all passersby.

She truly seemed to be the happiest person alive — one would never dream that she was the only survivor in her family, her sister, Sarah Rochel, collapsing dead in her hands on the day of liberation.

The book winds down as Zeidy describes his wedding, his three beautiful children and his, at the time, 18 grandchildren. The book concludes.

Baruch Hashem, my wife and I have a lot of nachas so far. Im yirtzeh Hashem, the nachas should multiply and intensify. Simply for this nachas of watching the mishpachah grow and seeing each family member climbing to great heights, it was worth surviving and witnessing the nekamah on Hitler yemach shemo.

Many knew Shloime Yunger to be a proud Berbester. They all thought this entailed a certain old-style sense of humor, a fine taste for herring and schnapps, and unbeatable negotiating skills. Zeidy did not tell them otherwise.

But his memoirs reveal the true story. Being a Berbester means possessing superhuman strength. It means laughing in the eyes of death, and refusing to relinquish the will to live. It means clinging to memories of a ravaged past and building a future upon its foundations. And it means loving your family with greater passion than the most virulent hate can ever imagine.

I was proud to join the family and be counted as a Berbester.

But I came to realize that that’s wishful thinking. It takes a whole lot more than that. Zeidy’s opening sentence said it best.

It’s not simple to be a Berbester.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1072)

Oops! We could not locate your form.