The Warmest Pesach

Yisroel Besser relives three days sans power in Montreal

Wednesday, Erev Pesach.

Frost on Erev Pesach isn’t unusual in Montreal, and some years fresh snow falls softly on the bi’ur chometz fires. It’s not a big deal here; people go about their business largely disregarding the weather.

Just before Pesach this year, when it started to rain — a slushy, weird sort of drizzle — there were the inevitable pictures sent by friends in Florida: cobalt skies and gently waving palm trees and “there’s still time to hop on a plane lol.”

The drizzle turned into a freezing rain, a peculiar mix that stayed icy as it fell. It was interesting, but who had time to sightsee on Erev Pesach — there’s always one more trip to the grocery store, did someone pick up the pants from the cleaners, and wouldn’t a nap be nice?

I happened to be in line at One Stop Kosher (again!) when the power went out, but no one made a big deal of it. It would go on in no time, we assumed. The tech-savvy ones checked the reliable Hydro Quebec app, which informed us that power would return within two hours.

I headed home, trying to pretend this was a regular blackout, but it was clear that it wasn’t. There was something faintly eerie about the app’s initial picture of the stricken areas, as if someone had taken a pencil and tried to perfectly partition off Montreal’s frum neighborhoods and ignore the rest of the city.

Something weird was going on.

As the day progressed, I stood on the porch and looked out at what appeared to be a Gadi Pollack illustration of the Makkos come to life, complete with creepy audio.

The freezing rain was not landing on the ground, but rather, coating each individual branch of the large maples lining the streets with layers of ice, as if a collector had put each branch in a protective case to keep it whole. It was beautiful. For about 30 seconds. And then we heard the first snap and just like that, a large branch — 15 feet long — simply snapped off the tree, unable to bear the weight of the icy coating. It fell to the ground, where it dented the hood of a car.

All down the block, people were moving their cars out of the shade of the trees, pulling into driveways, walking gingerly to avoid what was becoming a hail of falling branches.

Then a towering tree a few houses down — not a branch, but the tree itself — danced this way and that for a few moments, like a drunk person trying to find balance, and then it, too, toppled over, easily slicing a wire in two. Now the two wire halves were swinging back and forth over the slick, wet road.

Soon enough there were live wires all across the road, and city emergency crews arrived. They tried vainly to rope off roads and alleys, running yellow caution tape from private garbage cans so that the street looked like a construction site gone wrong.

My phone’s battery was at two percent when the shul email came in directing people not to go to shul on that night — leil hiskadesh hachag! — because of the danger posed by live wires, fallen trees, and total darkness in the streets. We were about to welcome Pesach in the dark.

Wednesday Night, First Seder

Most people davened locally that night, forming minyanim with immediate neighbors, faces illuminated by candles and dollar-store lanterns as the songs of Hallel rose to the darkened sky.

Then it was time for the Seder. Those who had been planning to eat at the homes of their parents or children had to adjust their plans on the spot or risk walking almost blindly through streets strewn with more obstacles than the highest level of those handheld games we used to get for afikomen gifts in the 80s, in which you sidestepped a landmine to encounter a trapdoor. Women had to contend with the fact that their stoves and ovens were useless and menus would have to be adjusted.

The thing is that none of the magazines have a “foods that can be heated by tea lights” recipe set. Some invisible Hand had altered the tablescapes they’d envisioned — the dishes, tablecloth, and flowers weren’t really visible, but if you positioned the candles well, you could make out the words of the Haggadah.

And the men? The ones who had spent days, maybe weeks, preparing what they would say, excited to transmit the songs, stories and ideas they had received from their parents to a new generation? It takes work to muster up that same enthusiasm in a dark, cold house — and cold was becoming an issue with temperatures below zero outside and no heat inside.

Okay, it was only one night. Maybe there would be power by morning.

All over the city, Yidden sat at their Seder tables and did what Jews do.

We dug deep and found strengths we’d never known (Mrs. C. Neuhaus, “A Yid”).

Comparing notes with friends in the coming days, I learned that we had all reached for similar messages as we started that Seder, bolstering our children and ourselves with the reminder that true cheirus means not needing life to be a certain way, not having a list of conditions that had to be met, in order to feel joy and meaning.

Across the city (later, we would learn that over one million Montrealers were without power, crews were working all night, and workers had been bused in from provinces across Canada to help), people cowered in their homes, while we sat around a table and sang. Even if people wore fleece hoodies to the Seder and the brisket was lukewarm, it was a Seder not just as nice as other years — but in a certain way, even nicer: There is something about feeling that you have gone me’afeilah le’orah, from darkness to light, even though you can just discern the shapes of the people around you.

Thursday Morning

Daylight did not bring power.

Men found pre-Shacharis coffees at one of the homes or shuls that had power, gas, or generators.Those families that had, sent covered hot- cups of steaming water to homes up and down their blocks so women could enjoy coffee, too.

In shul, we davened by the gray light filtering in through the windows, and after davening, there were three announcements: One was that Hatzoloh members were cautioning those using tea lights to heat their food to make sure to leave the oven door open to avoid accidents; the second, that those who had what to share — one shul member has a generator and several others have gas ovens — were opening their homes to anyone who needed oven space, a meal, warmth, or a bed; third, that if there was still no power by evening, we would daven in a different shul that did have power.

On the way home from shul, I felt like a UN observer being led through a disaster area, the crack, crack of tumbling branches the background music as we dodged piles of fallen trees and came home for a seudah.

The daytime seudah calls for more than the Seder in terms of food, and the women took their juggling act up a notch.

There were a few options when it came to heating up food. Some lived near those fortunate souls who never lost power (there were a few homes within the frum community who were blessed that way), or had generators. Most blocks had a few residents with gas cooktops, and those homes were opened wide for public use.

Still, it was a challenge: There were often lines for each burner, and with people waiting, mothers had to decide which foods to prioritize, and take them off as soon as they reached room temperature so that someone else could heat up their food.

Those who do all their cooking on Yom Tov were stuck with no way to cook, and one friend of my wife served scrambled eggs — the only food she could cook with tea lights — and matzah, rather than “mish” and eat food prepared elsewhere.

We had Sternos in our house, and as effective as they were at keeping food warm, they cannot bring anything to a boil, so once those meats that could be served at room temperature were used, my wife ended up sending the children to fry schnitzel at a neighbor with a gas cooktop. Salad options were limited, because the lettuce had gone bad. We opened the fridge sparingly, aware that each time the door opened, we were jeopardizing its contents. Milk for the babies’ bottles and for coffees was moved to the porch, which kept it fresh for a bit longer.

We tried not to think about the freezers and their contents, products of so much work, as we enjoyed the seudah.

There was no Yom Tov visiting and it was hard to nap, because the houses were growing colder. Older residents were starting to suffer from the sort of chill that creeps into the body, and rabbanim were advising them to move — even if it meant going in a car driven by non-Jews — to the homes of the handful of people who had power, or at least a gas stove that could provide warmth.

Information was passed around informally, the men picking it up in shul and women circulating between the homes of neighbors sharing news — who had gas stoves, who had heard a tidbit from a Hydro worker, innovative ways to keep food fresh for longer. (And sometimes, simply to vent the frustration that they would not share in their own homes, where little people were looking to them for clues, hoping for reassurance that this wasn’t a big deal. At the neighbor, without your kids watching, you can give the smile a momentary break.)

In a derashah, Rav Aryeh Kerzner, rav of Agudath Israel of Montreal and of the local Hatzoloh, spoke about the fact that Hatzoloh had come in to Yom Tov short-staffed, and most of the radios had no power. (Over Yom Tov, members would charge their radios in the shuls that had power.) Even though most years, the Seder night brings a number of calls, this year, with very few members available, it had been unusually quiet, even with the fallen trees and live wires. Hashem was making the Yom Tov a bit more challenging, perhaps, but He was also carrying us through it, allowing us to “brighten like the light of day the darkness of night.”

Thursday Night, Second Seder

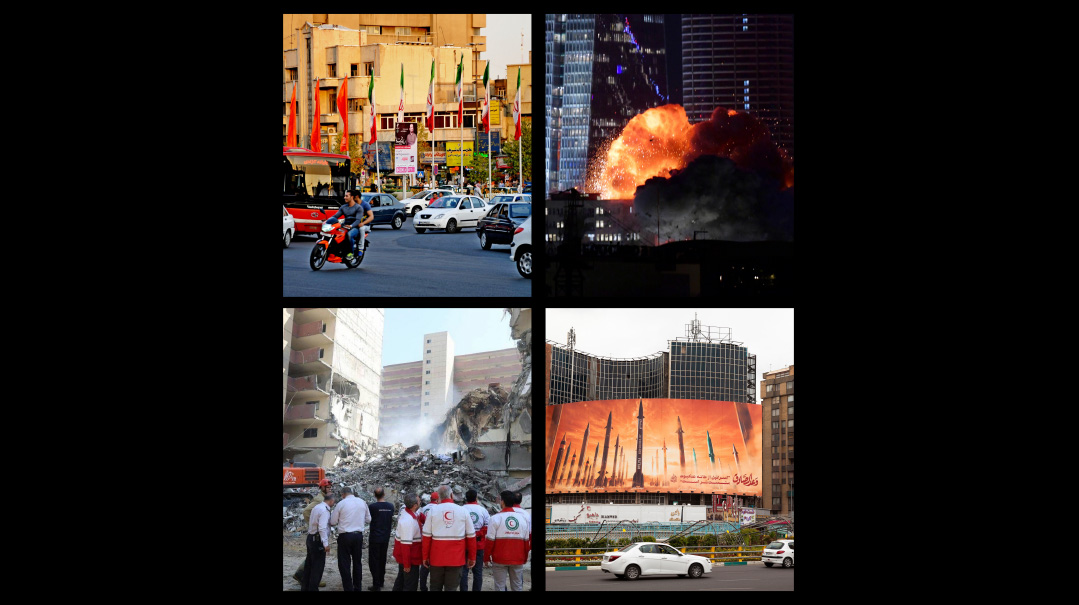

The second Seder took a bit more work; it was no longer all that thrilling to rise to a challenge. It was an opportunity to speak of emunah, of the meticulousness of His plans, of Hashgachah pratis — and it was clear how precise this all was. Had the temperature been a half degree colder, as in areas north of Montreal, then the ice would have fallen as hail, doing no damage at all, and a half a degree warmer, as rain, equally harmless. The frum communities of Outremont, Côte-Des-Neiges and Côte-St-Luc were the epicenter of the perfect storm and we were being given an opportunity to grow and feel surrounded by His love precisely when it was colder and darker than we were used to. Again, we read the Haggadah and measured our kezeisim by the light of battery-operated lanterns whose light was already dimming.

Some houses stayed relatively warm, but in others, the temperatures dropped further. People sat in their coats, swaddling babies in two pairs of pajamas and thick socks.

The second night brought a restless sleep, people dreaming that light had been restored — hopeful, anxious, and fidgety even in slumber.

Friday Morning

WE were sure that we would wake up to power on Friday morning (and some people did — several more blocks had power restored overnight), and when we did not, the disappointment hit hard. We opened our eyes to the same pencil-sketch of gray hallways, tables and chairs. There was a sense that this might never end.

Even though the Kollel had power, the pre-Shacharis coffee I had there was lukewarm. So many people were coming to drink that the urn was being filled and refilled too quickly to heat up properly.

After davening, there was an announcement that surprised no one: The eiruv was down. Shabbos was coming and there would be no more heating up food elsewhere, since carrying is forbidden. (In the “downtown” chassidish neighborhood, they did manage to get the eiruv up, in part.)

The rabbanim — charged with answering, problem-solving and encouraging — were forced into another zone as Shabbos approached. Over 3,000 years after Hashem took us out of bondage to stamp us as His own, we scurried through the streets in hoodies and scarves and spoke of amira le’akum and shevus d’shevus, of eiruvei chatzeros and which families would be eating where, a language He taught us back then, a nation of princes reflecting royalty.

At one point, the non-Jewish help sent by my wife’s friend (shout-out to Mrs. H. who knows that my wife needs a clean house even when no one can see it) arrived with new Sternos, reading the situation correctly.

Hydro Quebec trucks were circulating in the streets as Shabbos approached, and trustful women started to prepare the cholent. At 6:30 p.m., 41 minutes before candlelighting, power was restored in about 75 percent of the Jewish neighborhood.

Husbands and children ran out to find non-Jews who could help set the lights and ovens properly, and mothers joyfully spiced the cholent one more time, rooms bathed in light.

In my own home, we tasted this joy for about 45 minutes. But the surge of electricity was too big for our old wires and with a boom, the transformer outside our house blew, fire rising up and down the electrical poles. We were back in the dark.

Shabbos

Shabbos arrived to a dark home, but we had benefited from a few minutes of heat and our house was appreciably warmer. The menu called for new layers of improvisation and creativity from the nashim tzidkaniyos in whose merit we were redeemed from Mitzrayim. There were many families who had only cold food, while others, who had never before eaten a Pesach meal outside their own homes, went to neighbors with gas stoves to enjoy a hot bowl of cholent or glass of tea.

It was only after Havdalah that we set out to assess the effects of three days sans power.

With new batteries in our flashlights and tefillos on our lips, we opened the freezers to see what remained.

The Pesach sorbets and ice-creams the family so looks forward to, prepared with such love and toil, were given as a korban. Baruch Hashem, all the meats were still frozen. They had been packed well and that brief burst of electricity that had seemed a tease a day earlier, kept the freezer cold enough to get us to Motzaei Shabbos, when frozen food could be moved or extension cords run to neighbors with power. (We were fortunate. Some people forfeited the entire contents of their freezers, sustaining a significant loss.)

Motzaei Shabbos

Chapter Two started that night.

The simple son asks, ‘‘What is this?’’

Tell him: ‘‘With a strong hand did Hashem take us out of Mitzrayim, from the house of bondage.” (Shemos 13:14)

Tzaddikim saw a hint in this pasuk to the secret of our endurance in Mitzrayim and at every single stage of this long galus. The words “b’chozek yad” literally refer to Hashem’s strong Hand, but they can also be understood as a reference to the way each person strengthened his fellow Yid, lending his hands to the person beside him.

The strength one Yid gave to another is what earned us the merit to be saved. (Haggadah shel Pesach Be’er Emunah, Rav Elimelech Biderman)

Those who’d gone away for Pesach — people who left clean homes and anticipated returning to clean homes — didn’t hesitate, offering their homes to their neighbors who still didn’t have power. Shalach manos season made another appearance, as hot Melaveh Malkah trays and drinks were sent from house to house. Along with a huge shipment of generators and heaters sent by Chaverim of Rockland, Kiryas Joel, Central Jersey and Lakewood, which had arrived on the second day of Yom Tov, Ferrento.com, a tool and equipment rental business owned by two frum locals (Moshe Solomon and Nuti Meyer), opened on that holiday weekend, delivering generators, propane heaters and hundred-foot extension cords to dark and cold homes. Working through the night, the proprietors ensured that homes were warm and somewhat light that night, and that freezers would resume humming their comforting tune. The Chaverim members, who had spent the first part of Yom Tov helping the elderly and unwell, now got to work attaching, connecting, and instructing.

B’chozek Yad.

Some of those who still didn’t have power had a bigger problem than they’d initially realized: The electricity had been restored to their blocks, but their own electrical service masts, connected to their homes, were faulty.

Local electricians saw the opportunity to make a buck. They drove up and down the streets offering these desperate families to do a job that usually costs about two thousand dollars — for five thousand dollars.

Zev Fisher of Electriquecom also saw opportunity. He sent his trucks out and broadcast a message: If you know someone who needs help getting their main lines fixed, reach out. We will try to help out as much as we can…. Please feel free to repost….

He also changed his price for the occasion, charging zero dollars for the service. (His brothers Moshe Chaim and Hershy, along with Yiddy Karmel, enjoyed a Chol Hamoed activity that involved installing generators and teaching people how to use them.)

Rabbi Saul Emanuel at the JCC of Montreal launched a special campaign to help those families who had struggled financially to make Yom Tov and had now lost all their food, by offering vouchers at Fooderie, a local grocery store.

B’chozek Yad.

ON Sunday night, most of the remaining homes got power — as did we — allowing us to truly experience the simchah in gifts we likely took for granted: hot food, cold drinks, beautiful music.

That night, there was a special gathering. Rav Yehuda Mandel of Lakewood, one of the great contemporary disseminators of Novardok mussar through his Bitachon Weekly, spoke at the Dzibo beis medrash.

He quoted the words of Chazal, that “Achas b’tzaar, the reward for a mitzvah done with difficulty, is equal to meah shelo b’tzaar, one hundred mitzvos done without difficulty.”

“You, in Montreal,” he said, “have the merit of two hundred Sedorim, of two hundred mitzvos of achilas matzah, of eight hundred kosos of wine… because it was not easy to perform those mitzvos this year, it took more effort than usual.”

Then he stopped and said something that seemed a bit lofty, but each and every person — even as we daven that we never again experience a Yom Tov that is cold or dark, never again taste unpleasantness or worry — could relate to on some level.

“But in truth,” he said, “it wasn’t tzaar, it was wonderful…it was extra-special, even more than usual.”

That image — flickering candles, bodies drawn together for warmth, timeless words designed to allow us to touch freedom, the thrill of knowing that even when there is not much else, we still have the privilege of eating matzos mitzvah — remains, and the memory is sweet.

If those three days were a program, we might have billed it as “Pesach 5783 in Montreal”: stunning natural beauty, real-life thrills, surprise menu, great camaraderie, and inspiring speakers who might never have spoken publicly before but somehow found the right words.

I would not recommend it and would not willingly go back next year, but with all that, we say Thank You, Hashem, for Pesach 5783.

Thank You for helping us appreciate Your most basic gifts in a whole new way: ki le’olam chasdo.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 957)

Oops! We could not locate your form.