The War of Judgment

Forty years ago, Israel’s enemies rose up and attacked the Jewish people on their holiest day. It was indeed a day of fear and trembling

Who among us can approach Yom Kippur with confidence? Who is so sure that their good deeds outweigh their bad, that their repentance has reached G-d’s ears?

The Torah warns us not to feel overconfident. In Devarim (8:17), Moshe Rabbeinu implores the Jewish people never to forget the source of their blessings and think “kochi v’otzem yadi asah li es hachayil hazeh” — my strength and the might of my hand made me all this.”

Such was the position of Israel after the Six Day War. A stunning victory, a miraculous turn of events, had left Israel feeling swollen and indolent. Its Arab enemies had been pushed back to easily defensible lines; Israeli soldiers were stationed overlooking the Suez Canal. What could possibly go wrong?

On that terrible day in October of 1973, Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau heard the blast of the air raid siren in a Tel Aviv shul, Haim Sabato was a soldier on the front lines, Rabbi Tzvi Hersh Weinreb was a stunned mispallel in faraway Silver Spring, MD, and Ambassador Yehuda Avner was in the highest echelons of Israel’s government. After the war, Rebbetzin Esther Jungreis would visit soldiers maimed by the war in hospitals across Eretz HaKodesh. Their memories of that fretful day, detailed for Mishpacha here, are no less powerful 40 years later.

--Gershon Burstyn

The Rav of the Wounded

By Rav Yisrael Meir Lau

When the war began, I was naturally in shul. It was 1:45, and in the middle of Eileh Ezkera, the sound of a siren pierced the serenity of the holy day.

“Already from that morning, we had sensed that something was about to happen. I was davening in Tiferes Tzvi, a shul on Rechov Herman HaKohen in Tel Aviv. The shul had 930 seats in those days, and on Yom Kippur it was so packed with people that they even crowded the spaces between the benches. As the davening progressed, the young men in the shul steadily disappeared. Every once in a while, a military jeep or command car would pull up to the entrance to the shul, and a young man in a tallis would be pulled out of davening and sent straight to the front. When the siren went off, we looked around and saw only women, children, and old men.

I was a reservist in the military rabbinate, and I served as a lecturer for 25 years and three months. At the beginning of the war, of course, no one needed my services, so I wasn’t called up. On the morning after Yom Kippur, in consultation with Rav Pinchas Scheinman zt”l, the head of the Religious Council of Tel Aviv, I stationed myself in Ichilov Hospital in order to provide physical and spiritual aid to the wounded and their family members. I was given a white coat and a badge that said that I was in service, and for three months — day and night, on Shabbos and during the week — I was the rav of the wounded. Ichilov Hospital was cleared of all civilians and became a military hospital.

The hospital took in 475 wounded soldiers, all of them from the Suez Canal and Egypt and all of them in critical condition. One of the wounded, whose right arm had been crushed, was a young medical student, a religious boy named Naftali Rubinstein who wanted to be an orthopedist. He said to me, “My career is over. If I am ever able to lift a spoon to my mouth, it will be a miracle. I don’t dream of ever being able to perform surgery.” Today, that Naftali Rubinstein is the head of the orthopedic department at Ichilov.

Every minute that I spent in the hospital during those months was a highly emotional experience. About ten years ago, a woman named Molly Kedar, who was a volunteer in the hospital at the time, organized a reunion of all the patients from that era — those who survived. She invited me to come; it was the first time in 30 years that I saw some of those people.

A man named Moshe Shemesh came over to me and said, “I’m sure you don’t remember me, but for 30 years, I have been remembering you every day. I came to the hospital with burns all over my body; there was not even a patch of skin remaining. Even my nose had been burnt. Only my eyes were unhurt. There were many others like me, but I was still unique; I was the only injured soldier who had no one at his side. I didn’t have a father, a mother, a brother, or a sister. Only you, the rav, sat beside me and tried to talk to me. You realized that I had parents, but I didn’t allow you to call them. My mother was ill, and I was afraid that she would die from the shock of seeing me in this state. My eyes, after all, were uninjured, and I was able to see how my friends looked; I understood that I looked terrible. You sat at my side day and night, and you spoke to me. You told me that my parents were frantic; they were running to every military cemetery in search of me. You told me that the professor had promised you that I had a chance of survival, and you tried to convince me. You were the one who contacted my mother; you told her that I looked horrendous, but you had also seen others who looked worse than me and who had recovered. You brought me over to a public phone, and you stayed with me until you heard me say, ‘Abba, Ima, I’m alive. I’m on the fourth floor, Surgical Ward One, on the right hand side.’$$separate quotes$$”

When Moshe Shemesh finished his story, I said to him, “Moshe, not only do I remember you, but I also remember what you used to call out when you came. On those sleepless nights, you didn’t cry out in pain. You called the names of your friends, asking why they didn’t bring reinforcements.”

At the reunion, I told the story of a boy who was burned from head to toe and could not stop screaming in pain. All the morphine in the world could not calm him. The nurses yelled at him, his roommates yelled at him, I tried to speak to him, but nothing helped. Day and night he screamed and screamed, heartbreaking screams of devastation. One day, his mother came to the ward, sat down beside him, and found a tiny patch of natural skin on one of his legs. It was a tiny patch of skin, but she stroked the spot slowly and murmured, “Calm down, motek. Calm down, rest, you need to sleep so that you’ll have the strength to be healthy. It’s Ima speaking to you; sleep, my child. You’re not alone; you must sleep so that your friends can sleep, too.” This took about three minutes, and then he fell asleep, and there was silence in the ward.

I left that room in tears. I called home and said, “Now I understand a pasuk. There is a pasuk at the very end of Sefer Yeshayah, which we read in the haftarah for Rosh Chodesh, in which Hashem tells the Jewish people, through Yeshayah HaNavi, ‘Like a man whose mother comforts him, so I will comfort you.’ It is a beautiful pasuk, and we read it and think we understand it, but I saw this with my own eyes. Nothing else helped — not injections, not pills, not the shouts of the nurses and his roommates, not the words of a rav or the orders of his doctors; nothing calmed this man like his mother’s voice and touch.”

One of the thirteen principles of emunah is that we believe in the words of the neviim. We have faith that this will happen, and we wait for Hashem to console us, just like a mother, very soon.

Rabbi Israel Meir Lau is the chief rabbi of Tel Aviv-Yaffo and former chief rabbi of the State of Israel.

A Bracha Before Battle

By Haim Sabato

A pure moon shone overhead. Not a cloud hid it from sight. It was waiting to be blessed by the People of Israel, as shy as a bride who waits to be veiled by her bridegroom before stepping under the wedding canopy. Ever since the moon said to G-d long ago, “The sun and I cannot rule as equals and share the same crown,” and the Creator rebuked it, saying, “Then wane and be the lesser light,” the moon has humbly accepted its fate. Whenever it shines, humbleness shines with it and gives it grace.

Row after row of Chassidim danced before it. The younger ones wore black gabardines, the older ones, white gowns. The gowns looked like shrouds. They reminded a man of the day of his death, that he might observe the counsel of Rabi Akavia ben Mehalalel, who said: “Think of three things and thou will not come to sin: from where you have come, to where you will go and to Whom you owe a reckoning.”

Gabardined and gowned, the Chassidim shut their eyes and swayed, aiming their hearts at Heaven and chanting, “As I dance before Thee but cannot touch Thee, so may our enemies dance before us and neither touch nor harm us. May dread and fear befall them!”

And they repeated:

“May dread and fear befall them!”

And a third time:

“May dread and fear befall them!”

It was the end of Yom Kippur. It is the custom at the end of this day for the People of Israel to sanctify the moon with a special blessing. Cleansed of all their sins, they are supposed to perform a commandment at once, before the Satan, envious of their purity, could find a way to entrap them. And all the more is this so because sanctifying the moon is like playing host to G-d, for it is written in the sayings of the Sages, “Were Israel to do no more than greet their Father in Heaven once a month at the sanctification of the moon, this would suffice.” Hence the moon is sanctified standing, as if in the presence of a king. Moreover, as G-d is present in joy, and joy comes from purity, and the People of Israel are pure at the end of Yom Kippur, having stood all day in prayer and confessed their sins and abstained from food and denied themselves the pleasures of the flesh and cast off all material things until they are likened to angels, a herald voice declares, “Go, eat your bread in joy, and drink your wine gladly, for the Lord is pleased with you.”

In most synagogues, so as not to prolong the ordeal of all those fasting, especially the elderly, the ill, and women with children, the evening service is said immediately after the blast of the shofar that marks the end of Yom Kippur. As soon as the day is over, the congregants sanctify the moon and hurry home.

This was the practice in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Bayit Vegan. Though many of its inhabitants were pious Jews who prolonged their Sabbaths and holidays according to the strict ruling of Rabbeinu Tam, they too had long been at home, the hour being close to midnight. Who, then, were the Chassidim awaited by the moon? They were the disciples of the Rabbi of Amshinov. Loath to part with the rapture of prayer, the Amshinov Chassidim lingered over it even on Yom Kippur, extending the holiness of the fast day into ordinary time.

I was glad to see them still dancing. I had begun to think I would have to sanctify the new moon by myself, without a minyan. Where was I going to find ten men at such an hour? And most of all I was glad because the Sages had said that whoever sanctifies the new moon in joy would come to no harm in the month ahead. I was about to mention this to my friend, Dov, walking at my side, so that he could put himself in a joyous mood, when the Chassidim pulled us into their ranks.

“Soldiers!” they cried. “Soldiers! Go to the rabbi and he’ll bless you.”

They parted to make a path and we were led to the rabbi, the old Amshinover Rebbe. His Chassidim crowded around us.

We were two young soldiers, Dov and I. Our packs on our shoulders, we made our way to the rabbi. We had been together since coming to Israel, Dov from Romania and I from Egypt. Each day we had walked from Beit Mazmil to the Talmud Torah in Bayit Vegan, Dov in his black beret and I in the brightly colored cap I was given by a woman who worked for the Jewish Agency in Milan. My family had been in transit there from Cairo, waiting for the night train to Genoa, from where we would sail to Haifa on the Artza.

The Talmud Torah in Bayit Vegan was next to the Amshinov synagogue — outside of which, 13 years later, we now stood near the buses parked at our assembly point. As soon as our bus was full, an officer would take charge and we would head north to our unit.

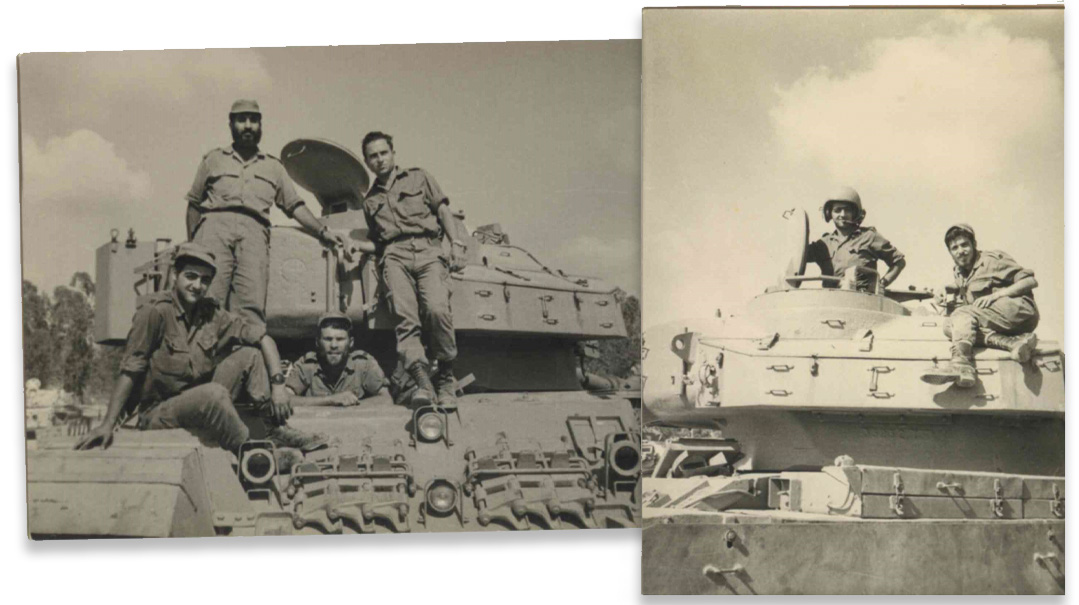

We had studied together at the same religious high school, Dov and I. We had gone together to the same yeshivah, whose students divided their time between their studies and the army. We had trained in the same tank at an armored corps base in Sinai. I was the gunner. Dov was the loader.

“Crew, prepare to mount the tank! Crew, mount! Driver, sharp left! Gunner, hollow charge, 2,000 meters, fire! Down a 100, fire! Up 50, fire! Direct hit! Direct hit, hold your fire! Loader, reload! Faster, Dov! Stop dreaming! There’s no time to dream in a real war. You’re already in the enemy’s sights.”

“Yes, sir. I’m doing my best.” The loader opened the breech.

We stood watch together on a roof in Ras Sudar. We manned its southern position, looking out over the Gulf of Suez, Dov and I.

It was a Sabbath eve. Dov had finished his watch and I had come up to relieve him. It was pitch dark. There were no stars or moon. We had just finished our basic training the month before. Every splash of a fish in the water made me jump. Dov said, “I’ll stay up with you. I can’t sleep anyway. We can sing Sabbath hymns. Or go over a bit of Mishnah by heart.” I knew he knew I was afraid. He stayed with me.

In theology class we had argued together about faith, and belief in G-d, and Redemption. Together we had studied Rabbi Nissim of Gerona’s commentary on the second chapter of Kesubos. Together we had read The Maharal of Prague’s Eternity of Israel. And together we had parted from Dov’s mother on Brazil Street in Beit Mazmil an hour before.

“War,” she had said. “War! What do you know about it? I know. And I know no one knows when you’ll be home again. No one.”

As she spoke she filled a tin with homemade cookies and another with cheese pastries wrapped in foil. I knew the taste of both.

“Ima!” Dov said. “This isn’t Romania or World War II . Think of it as a school outing — we’ll be back in a few days.”

To me he said softly, “I understand how she feels. She’s worried. Her whole family was killed in Europe. And she’s a mother. But this is just one more glorified company maneuver. We’ll be back in no time. I heard on the radio that we’re already counter-attacking. The air force is knocking out the Egyptian bridgeheads on the Canal. I’m only afraid that by the time we reservists get to the Golan, the regular army will have finished the job for us.”

His father put down the little book of Psalms that he was reading. He kissed it and kissed his son.

At the end of Yom Kippur, together we walked to the assembly point. Close to midnight we were brought to the Rabbi of Amshinov by his Chassidim, who were sanctifying the moon. Their rabbi, they confided, could work wonders. His blessing was worth a great deal. They stood around us, straining to hear what he would say.

The Rabbi of Amshinov clasped my hand warmly between his own two and said, looking directly at me:

“May dread and fear befall them. May dread and fear befall them. Them and not you.”

We parted from him and boarded the bus. We thought we’d be back soon. During the three terrible days that followed, I kept seeing the Rabbi of Amshinov before me. I kept hearing his words. Each time fear threatened to overcome me, I pictured him saying, “Them and not you. Them and not you.” That calmed me.

Until I heard of Dov’s death.

After that the old man stopped appearing.

The months went by. In late spring we hosed down our tanks a last time, handed in our gear, took off our uniforms, and returned to the Talmud — to the tractate of Bava Basra and the property laws of pits, cisterns, caves, olive presses, and fields. I kept meaning to go to the Rabbi of Amshinov and tell him what had happened to us after he blessed us. I wanted to tell him how our tanks were knocked out in Nafah quarry on the second day of the war, and how they burst into flames one by one, and how the blackened loader of 2-b hit the ground with his leg on fire and rolled there dowsing it with a jerry can of water. And how our tank commander Gidi shouted, “Gunner, fire!” and I shouted back, “I don’t know what to aim at!”

“Fire, gunner! Fire at anything! We’re being shot at! We’re hit! Aban-don tank!”

And how Roni the driver said quietly, “I can’t get out, the gun’s blocking the hatch,” and I crawled back in to free him, and the four of us ran over terraces of black earth with the bullets flying around us, and Eli said, “I can’t go on,” and we forced him to. And how Syrian commandos jumped out of a helicopter right ahead of us. There was even more I wanted to tell him — of the thoughts I had, and the prayers I said, and the things I shouted to G-d and promised Him.

It was just that, each time, I thought: When I’m done the rabbi will ask in his gentle voice, “What happened to the friend who was with you that night?” And I would have to lower my eyes and tell him, “Dov is dead.”

It would have made the old man sad. And so I never went to see him. I stuck to my Talmud with its laws of houses, cisterns, pits, and caves. The years went by. I couldn’t put it off any longer. I’ll go see him, I thought. Whatever will be, will be. I went to Bayit Vegan and found some Amshinov Chassidim.

“How is your rabbi?” I asked.

“Just a few hours ago,” they told me, “his soul departed this world.”

Excerpted from “Adjusting Sights” with permission from The Toby Press.

Rabbi Haim Sabato is a Cairo-born Israeli rabbi and author. Born to a distinguished family of Aleppan descent, Sabato moved with his family to Jerusalem as a young child in the 1950s. He cofounded the hesder yeshivah Yeshivat Birkat Moshe in Maale Adumim in 1977.

Prophetic Words

By Rav Moshe Yaakov Perl

It was the night before Yom Kippur in the Yeshiva of Telz, the night when the revered Rosh Yeshivah, Rav Mordechai Gifter ztz”l, traditionally delivered a shmuess. I was one of the older bochurim in the yeshivah at the time, and we all gathered, as usual, in the beis medrash to hear the Rosh Yeshivah’s inspiring words. The large removable walls at the back of the room had been opened, as they always were during the Yamim Noraim, but the room was still full; the entire student body of the yeshivah gedolah was there, numbering about 200 bochurim, as well as the kollel of about 50 yungerleit.

The Rosh Yeshivah was always a passionate, emotional speaker, and this year was no exception. (Someone once remarked that a person could fulfill the mitzvah of tkiyas shofar simply by hearing Rav Gifter’s booming voice reciting the psukim before the tkiyos.) As always, Rav Gifter wept several times during the shmuess. To us, there was nothing unusual about this, and we thought nothing of it at the time. I realized only recently, when I heard that year’s shmuess again on a recording, that Rav Gifter’s words were laced with what seemed like a prescient knowledge of what was to come.

The topic of the shmuess was the nature of Divine judgment. It was a beautiful talk with many parts, and the Rosh Yeshivah moved us all greatly. Toward the end of the shmuess, he quoted Rabbeinu Yonah, who writes that when a severe punishment has been decreed on a person, there are certain things that he can do to lessen the severity of that punishment. The Rosh Yeshivah cited the example of putting extra effort into one’s learning; the toil and struggle involved will count in place of the harsh retribution that the person was supposed to receive. When the Rosh Yeshivah mentioned this point, he thundered, “This will be a tris bifnei hapuranuyos — a shield from Divine punishments!” This alone may not have been unusual, but the Rosh Yeshivah proceeded to repeat these same words twice more before concluding the shmuess.

The next thing the Rosh Yeshivah mentioned was that a group of older bochurim had approached him with a suggestion. In Telz, the yeshivah did not allow the boys to leave on Motzaei Yom Kippur; unless Yom Kippur was close to Shabbos, we were required to stay at least until the following morning. At the same time, there was no schedule in place for the night after Yom Kippur, and the boys often frittered away those hours in their rooms in the dormitory. A number of bochurim had approached the Rosh Yeshivah that year and asked him to schedule a learning seder for the night after Yom Kippur. After all, they had pointed out, how could we allow the precious hours after the holy Yom Kippur davening to be squandered on frivolities? In that shmuess, Rav Gifter announced that he had been pleased by the request, and indeed, beginning that year, there would be a seder scheduled for the night following Yom Kippur. Once again, he repeated those chilling words: “It will be a tris bifnei hapuranuyos!”

And that was not all. Before he ended the shmuess, the Rosh Yeshivah announced when the winter zman would begin and which masechta we would be learning. The masechta that year was Kesuvos, and the Rosh Yeshiva announced which perek we would be studying during the morning seder. Then he added that he felt it would be a good idea for the entire yeshivah to learn the same perek during the afternoon seder, as well, rather than splintering into separate groups learning different prakim. Again, the Rosh Yeshivah concluded, “This will be a tris bifnei hapuranuyos!”

The unusual repetition did not attract much attention at the time, but years later, we have come to recognize what puranuyos the Rosh Yeshivah must have had in mind. Chazal tell us that chacham adif minavi — a Torah sage has more prescience than a prophet.

For many months, the Rosh Yeshivah was deeply affected by the situation in Eretz Yisrael. At a wedding in New York shortly after the war began, Rav Gifter suddenly called for the dancing to stop and announced, “We must say Tehillim for the matzav in Eretz Yisrael!” The entire wedding party then spent a few minutes saying Tehillim. And the Rosh Yeshivah never ceased reminding us in his shmuessen throughout the war about the bitter plight of our Jewish brethren overseas. Somehow, it seems, his great heart sensed the impending calamity even before it began — and during that shmuess, he shed tears for the disaster that was about to strike the Jews of Eretz Yisrael.

The Secret Power of a Medallion

By Rebbetzin Esther Jungreis

There is a popular adage: “Yesterday’s newspapers are today’s trash.” It is so easy and convenient to forget the past. And herein lies the tragedy of mankind: We fail to learn from the past and keep repeating the same old, same old.

While this holds true for all nations, it is especially destructive to us, the Jewish People. We fail to understand that everything is a wake-up call from Hashem. Let us try to comprehend the message of that very painful Yom Kippur War. What is the wisdom that we must glean from it, and to what end must we absorb the lesson behind it? I do not pretend to be a rebbe or a mekubal; I’m a simple Jewish woman. I try to understand and share my perspective with others.

The Yom Kippur War was a defining moment in the young State’s history.

Six years earlier, in the wake of the satanic Holocaust and the bloody battles for Israel’s independence, Hashem gave us a miracle that buoyed, elevated and strengthened us — the Six Day War. Those days were nothing short of spectacular. In six electrifying days, we liberated Yerushalayim, and after almost two millennia the Kosel once again became ours. We blew the shofar, we washed the ancient walls with our tears. We came to Chevron. We davened in Mearas HaMachpeilah — the resting place of our Avos and Imahos. We sobbed at Kever Rochel. Kol b’ramah nishma, Rachel mevakah al baneha. We cried with Mama Rochel, tears of consolation and joy. The miracles were spectacular and they came quickly, one after another. At all our borders, those who swore to annihilate us, to drive us into the sea, became putty in our hands.

How, you might ask, did we merit these open, stunning nissim? The answer is simple: achdus and ahavas Yisrael.

Then came our tragic downfall.

We became shikurei nitzachon — drunk with victory. With insolence, we proclaimed: “Kochi v’otzem yadi asah li es hachayil hazeh — my strength and my power accomplished all this!” We became arrogant and forgot that it was Hashem who leads us in battle and it is He Who is responsible for our triumph.

It is against this background that we can comprehend the meaning of the Yom Kippur War. It took us by surprise; it was totally unexpected. It came from nowhere. But it occurred on Yom Kippur, and that, in and of itself, should give us all pause. Yom Kippur, when each and every one of us stands in judgment before G-d, when the message is loud and clear: “Lifnei Hashem tit’haru — Cleanse yourselves before Hashem!”

We were in our shuls, engrossed in our tefillos, when the shrill sound of the siren jarred us into tragic reality. The call-up came. Everyone had to report. Everyone had to be at the battlefield. It was Yom HaDin, a wake-up call from Hashem.

Did we learn from it? Did we get it? Did we absorb it?

The Yom Kippur War was a defining moment for all of Israel’s battles. The message was loud and clear: It is Hashem Who leads us; it is Hashem Who protects us; it is He, and only He, Who enables us, a minuscule minority, to triumph over the giants and allows us, David, to topple Golias.

And now, allow me to share with you my own personal story that played out during those painful days.

The Yom Kippur War had left many dead and wounded. I felt that I wanted to do something to show, if only symbolically, that we cared, that we in America felt the pain of our brethren in Eretz Yisrael.

Our Hineni organization was in its very inception. In those days, all kinds of trinkets ornamented with logos and slogans were in vogue. We had Hineni buttons, bumper stickers, and T-shirts. I asked my husband, Rav Meshulam HaLevi Jungreis, ztz”l, who had wonderful artistic talent, to design for me a Hineni medallion in the shape of a flame spelling out the word Hineni in Hebrew. I wanted to present the many wounded soldiers in the hospitals with this medallion.

My father, Rav Avraham HaLevi Jungreis, ztz”l, encouraged me. “U’veirachticha … Di darfst teen, mein kind, und di brachah vet kummen — You must only do, my child, and the brachah will come.” And so it was that soon afterwards I met a man who was a jeweler and he volunteered to make up the medallions in silver as a gift for the soldiers.

A group of us set out to visit the hospitals and recuperation centers in Israel. A heartbreaking scene awaited us: men and boys without limbs, without eyes; their brokenhearted wives, children, and mothers hovering over them. The terrible price of war.

Accompanied by musicians and carrying trays of refreshments, we met the soldiers in the solarium; some were in wheelchairs and some in their hospital beds. I distributed the medallions and shared with them teachings of faith and hope from our Torah.

There were a number of wounded who were too ill to participate, and the head nurse asked if I would like to visit them in their rooms. “Of course,” I replied. “That’s why I came.”

I entered a room in which the light had been dimmed. The patient lay immobile in his bed, wrapped in bandages like a mummy. “Shalom to you,” I said. “My name is Esther Jungreis. I came from the States to bring you greetings, blessings, and gratitude.”

There was no answer.

“What is your name?” I asked.

Still the boy did not respond. The nurse explained that he had been badly burned in a tank battle on the Golan.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I know that it sounds hollow, and it’s only words, but please know that I mean it. I have brought you a little token, a symbol of blessing and honor.” And I held up the medallion.

For the first time, the young man spoke. “Take your medallion. It’s of no use to me!”

“I understand that you are hurting,” I said, “but I’m going to leave it on your night table, anyway. You might just need it one day.”

“For what?” came the angry retort.

“For an engagement gift,” I replied.

He let out a bitter laugh. “I’m no longer a man. Who will ever marry me?”

“I agree with you. You are no longer a man — you are a malach Hashem.”

“Me?” he repeated bitterly. “A malach Hashem? I’m a vegetable. No one will ever marry me!”

“Yes, you are a malach Hashem!” I said emphatically. “And I’ll prove it to you. It is written in our Torah that Avraham Avinu was the paradigm of faith — ‘V’he’emin baHashem’ — he was a total, uncompromising believer in Hashem. The Ribbono shel Olam promised him that he would inherit the Land for all time. Incredibly, Avraham asked, ‘Bameh eida? How do I know that I will inherit?’”

Avraham’s question stuns the mind. Would he, a man of total faith, question G-d’s Word? No, of course Avraham would never doubt Hashem! But he had vision. He saw a time when his descendants would tragically forget the Covenant and he feared that they would lose the Land. To which Hashem responded by charging him with bris bein habesarim — sacrifices.

“You,” I told him, “sacrificed. And therefore you are indeed a malach — a messenger of Hashem.

“You will see,” I continued, “it will happen. In time you will meet a girl, and when you do so, you must tell her that a rebbetzin from the United States visited you and told you that you have a special place awaiting you in Olam HaBa that you will share with her, and this medallion is a symbol of that.”

“Rebbetzin, if I said that to any girl, she’d think I’m crazy.”

“You’re wrong. Someplace, somewhere, there is one girl who will understand — and you need only one.” And with that, I walked out of his room, leaving the medallion behind.

A year later I was once again in Israel. This time, my first stop was at an army convalescent home near Haifa. At the conclusion of my program, a soldier in a wheelchair was brought up to the stage to present me with flowers.

“Do you recognize me, Rebbetzin?” he asked.

“You look familiar. Please help me out,” I responded.

He smiled and pointed to the young woman standing behind his wheelchair. “I would like you to meet my bride.”

I looked at the smiling face of the young lady, and then saw the Hineni medallion glistening on her neck.

The Yom Kippur War took many lives and left many of our sons maimed, wounded, and blind. But we are Am Yisrael, the children of Yaakov Avinu who wrestled with Eisav throughout the long, dark night. Yaakov emerged limping but triumphant, and he earned the glorious, majestic name Yisrael, Prince of G-d.

Yes, we are princes of G-d. We may be wounded, we may be hurting, we may have forgotten who we are. But we are the children of Yaakov Avinu. We are Yisrael!

Rebbetzin Esther Jungreis is an internationally known speaker and the author of four books, including her latest, Life Is a Test.

It’s All Right to Be Afraid

By Dr. Itzhak Brook

“I’m not going back.” The words, spoken in a tone of mingled desperation and fear, echoed in my ears. “I have a newborn son and a wife at home, and I’m afraid. I’m afraid that if I return to the battlefield, I won’t live to see my son again.”

I understood the man. Fear had been our constant companion since the beginning of the war. It dogged our steps on the battlefield, and it threatened to choke us as we struggled to mount a defense, fully cognizant that the enemy could strike us at any moment.

The soldier who had spoken was a member of my battalion. Each of us had been separated from the group during an enemy bombardment, and we had found our way separately to the same army base. I planned to stay there until the morning, when I would rejoin the others, having been given enough information to be confident that I would find them. The soldier, on the other hand, had other ideas.

Earlier in the war, I would have fought his decision. I would have insisted that he be strong, suppress his fear, and return to the battalion where he belonged. In fact, I would have threatened to have him arrested and charged with desertion if he carried through on his threat. As an officer, I could have done it. But my experiences in the war had told me that that approach was not always effective. In fact, it was fundamentally flawed.

“If you want to go home,” I told the man, “I won’t oppose you. I’ll leave the decision in your hands. In the morning, I am going back, and if you join me, I will take you along. If you do not, it’s your choice.” I paused, then voiced my own thoughts. “But if I were you, I would consider this. When your son grows up, will you be able to look him in the eye, knowing that you abandoned your fellow soldiers when you were needed?”

Whether he knew it or not, this soldier was not alone in carrying the crushing burden of fear. I, too, was terrified. Many of the soldiers were terrified. They would confide in me that they were gripped by fear, that they were deeply worried about their futures. And there were many good reasons for their feelings.

From the outset, the war was marred by the distrust we felt for our leaders and by the perilous, even helpless position in which we found ourselves. Many of us believed that if the country had been better prepared for the attack, there would not have been nearly as many casualties, and we ascribed the lack of preparedness to a governmental blunder. We also listened to our leaders as they spoke on the radio, reassuring the nation that we were winning the war, while we, on the front, knew — at the beginning, at least — that the opposite was true.

Alongside the loss of faith in our leaders, we had to deal with the ever-present and unavoidable threats to our lives. We knew that our enemies had weapons that could strike at us from 15 miles away, and we had no way of knowing when a missile was on its way. In my own battalion, the men had to drive trucks full of ammunition and gasoline to the battlefield, in full view of the enemy; many were shot at and incinerated while doing their jobs. We were vulnerable, unprotected, and helpless to defend ourselves or even to know when we were in immediate danger.

Under such horrific circumstances, who could fail to crack from the strain? An army driver gave me my first encounter with this profound, pervasive fear. He informed me with the utmost composure that he intended to drive off the battlefield, desert his unit, and return home. “I’ve had enough of this war; I can’t take it anymore,” he said matter-of-factly — and then floored the gas pedal and disappeared. Then there was the medic with whom I had worked for years, who simply collapsed on duty and lay trembling at the side of the road; I later came to understand that he was exhibiting the classic signs of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

And then there was the fuel tanker driver who came to ask me for valium pills to take on the battlefield. “I drive my truck around at the front lines, moving from one tank to the next and refueling each one while the others try to hold off the enemy. At any moment, I could be hit. I don’t think I can continue doing my job without something to keep me calm.” The man’s haggard and exhausted face confirmed what he was telling me.

“The sedative might impair your judgment or slow your reflexes,” I warned him. “In your situation, that could easily endanger your life.”

He understood the gravity of the situation. “I will take a pill only when I feel that I truly need it,” he promised me solemnly. I handed him a couple of pills, with instructions to come back if he needed more. I did not see him again.

Eventually, my own resistance to acknowledging fear began to wither. I came to realize that forcing soldiers to suppress their profound terror, to ignore their deep-seated fears, and exhibit a bravado they scarcely felt, was actually harmful to them and injurious to their performance. The turning point came when another soldier came to confess his fears to me and I decided to confide in him that he was not alone. “Of course you’re afraid,” I told the man. “How could you not be? Who wouldn’t be, under the circumstances? I am also afraid; everyone is.”

Relief immediately spread across the soldier’s face, and I knew that I had hit upon the key to dealing with the rampant, and eminently justified, fears of our troops: Acknowledge the fear. Validate it. Do not make the slightest effort to pretend it does not exist.

And what of the would-be deserter whom I told he was permitted to return home? The next morning, that soldier joined me in the truck that took me back to the battalion. To the best of my knowledge, he survived the war and was reunited with his wife and son.

Dr. Itzhak Brook is a professor of pediatrics at Georgetown University and the author of In the Sands of Sinai: A Physician’s Account of the Yom Kippur War.

False Confidence

Rabbi Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

I vividly remember Yom Kippur, 1973, although it is now 40 years ago. My family and I were living in Silver Spring, Maryland and I was an active member of a synagogue community known as the Summit Hill Congregation.

First, a few words about the community and about the role I played in it at that time. The community consisted of about 100 families, the majority of whom were young married couples with very young children. Most of us came to Silver Spring because it was near the settings within which we were beginning our professional careers. Some of us, like me, were in graduate school, others were doing their military service, still others were clerking for federal judges or beginning their careers in government civil service.

Most of the group had advanced Jewish educations, and a few of us had smichah and served as unofficial rabbis of the congregation. I already had smichah then, and gave sermons and shiurim. I also was one of the baalei tefillah, and was designated to lead one of the tefillos that Yom Kippur.

I must stress that, just six years earlier, everyone in our group had experienced the Six Day War, most of us from the safe shores of the United States. The victory achieved by that war left us all with a feeling that the Jewish people had triumphed over our enemies once and for all and were no longer vulnerable to the vicissitudes of the Galus.

We were full of hope and optimism.

That Yom Kippur morning, in shul, as the news of the attack filtered in from passersby, our first response was one of disbelief. We were convinced that Israel was beyond any possible threat.

Our belief soon dissipated as the reports began to become more and more detailed. Then we became conflicted between our need to hear those details and awareness that today was Yom Kippur and we should be preoccupied with the tefillos of the day.

But we all soon realized that the tefillos of Yom Kippur are almost without exception about beseeching G-d to forgive us. Slach lanu, mechal lanu, kaper lanu. Somehow, those tefillos felt, if not irrelevant to the emotions we were experiencing, then certainly inadequate to expressing our horrible fear and our need to plead with G-d for His protection.

I had been asked to deliver a drashah that day. I no longer recall whether it was before Yizkor or before Ne’ilah, but I clearly remember what I said. I urged the khal to focus on the prayers for forgiveness with greater kavanah then ever. I said that although we knew so few details, we do know that the Jews of Israel are in danger. We can pray for their survival, but our prayers will be more acceptable if we recognize our own shortcomings first, plead for G-d’s forgiveness, and then ask His protection.

I encouraged everyone to compose their own tefillos on this occasion, and to pray for the klal, for Israel as a whole, before praying for the individuals we knew who were in danger.

In the interest of candor, I must say that everyone in shul had great difficulty focusing on the davening that day. We were totally overwhelmed by the emotions of fear, the worry about loved ones in Israel, the shattering of our illusion that Israel would never again know war, and the furious anger we felt toward an enemy who would choose our holiest day to attack us. We were also distracted by the need to know the news of the war. All of this made it almost impossible to have anything even close to the proper kavanah for the prayers of the day.

This difficulty persisted into Succos, because rejoicing was so hard to do when we were by then fully aware of the extent of the danger and the volume of casualties and fatalities. Somehow we made it through Succos by concentrating on the news that was starting to come in that the tide had shifted, and that the defenders of Israel were stemming the advance of the enemy.

Very soon after Succos we arranged a community assembly which combined a briefing on the situation from a representative of the Israeli embassy in nearby Washington, D.C., with prayers of thanks, and with tefillos for a speedy and total resolution of the entire conflict.

Never again would we regain the degree of euphoria and false confidence that we had before Yom Kippur. It was a life changing and sobering day, that’s for sure.

Rabbi Tzvi Hersh Weinreb, Ph.D. is the executive vice president, emeritus of the Orthodox Union.

Winning the Battle, but Losing the War

By Binyamin Rose

Like any young man who reached the driving age of 17 in New Jersey, I was thrilled when I got my license in the spring of 1973.

Gas was cheap back then. I owned a Plymouth Fury 3 with a 318 cc engine, and I could hand the gas station attendant $5 after he filled my tank — there was no such thing as self-service — and I would even get some change back from the five-spot.

That all changed in the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War.

Toward the end of the war, the global oil cartel OPEC — an acronym for the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries — leveled an oil embargo on large parts of the Western world that had supported Israel during the war. America was one of the affected countries.

Almost overnight, gas prices shot up from 40 to 45 cents a gallon and within weeks, reached 55 to 60 cents. Now I needed to remember to bring a $10 bill with me when filling up – the equivalent, in percentage terms, of gas rising from $3.20 a gallon to above $4 between Yom Kippur and Chanukah.

Sticker shock was one issue; availability was the stickier one. The embargo caused gas shortages nationwide. Drivers had to line up at the few service stations that were open. Lines were long and tempers short, especially at rush hour.

Often, you might drive to your friendly corner service station, only to find they were flying a red flag, which meant they were out of fuel. A yellow flag meant limited availability, and you might just get enough gas for a couple of days and then have to play the whole game over again.

Lines were always longest at stations that flew a green flag showing that you could fill up, but sometimes, the color might change on you from green to yellow — or worse, to red — before your turn came up.

New Jersey instituted a system where drivers were only allowed to fill up on alternate days, based on whether your license plate number ended with an even or odd number. If your car was running low on gas and you plate number was the wrong one, you could be the odd man out, even if all you needed was a dollar’s worth to get to work.

It didn’t seem like America, the land of plenty. Not only that, but instead of blaming the Arab oil exporters who levied the embargo, some people started blaming the Jews, or Israel. There were even bumper stickers printed saying “burn Jews, not oil.” Others blamed the oil companies, claiming there were oil tankers idling offshore with plenty of fuel to end the shortages, but they were waiting for higher prices to sail to port.

I was a freshman in Boston University at the time, and often drove back and forth between college and my parents’ home in Passaic. During the course of the war and subsequent embargo, I found myself in spirited debate with a fellow on my dormitory floor of Lebanese ancestry, whose father owned a petroleum refining company. There was no doubt as to whose side he was on.

I suppose we could have become enemies, but our rivalry soon turned into a friendship. We discovered we were both big hockey fans. He rooted for the Boston Bruins while I was a New York Rangers fan. In those days, that particular rivalry was almost as fierce as the Middle East conflict, and in this case, the Bruins were the better team, so he got some satisfaction at my expense.

In the great scheme of things, I was quite content to see him win the hockey battle and lose the Middle East war.

Binyamin Rose is Mishpacha’s news editor.

A Harbinger of Things to Come?

By Yehuda Avner

As Arab mayhem, carnage, and volatility abound on every side — the abattoir that is today’s Syria, the Hezbollah savagery that is Lebanon, the uneasy crown that lies on the king’s head that is Jordan, the Hamas oppression that is Gaza, the al-Qaeda bloodbath that is Sinai, the regime of military government that is Egypt — Israeli forces on all fronts are on high alert. They are on high alert because in our merciless and unforgiving neighbourhood all IDF chiefs of staff choose to err on the side of caution ever since Israel was taken by surprise in the Yom Kippur War of 1973. Then, people in shuls heard with inexpressible astonishment as rabbanim interrupted the davening to announce that congregants in the reserves were to report to their units immediately.

A post-war Blue Ribbon commission of inquiry would conclude that had Israel's leaders put their ears to the ground they would have heard the rumble of the approaching chariots of war long before the juggernaut came. Yet even those who were listening were so duped by their own preconceived conceptions that they misread what they were hearing. The very idea of an Arab onslaught was an affront to Israel’s enshrined military doctrine which expressed certainty that neither Egypt nor Syria was capable of waging all-out warfare at that time. And much as actors at dress rehearsals reassure their anxious producers, “Don’t worry, it’ll be all right on the night,” so did Israel’s military reassure Prime Minister Golda Meir that everything was in hand.

But the IDF was caught napping. The thinly-held lines in the north and in the south were sent bleeding and reeling under the hammer blows of the combined Egyptian-Syrian attack, splintering and crushing the army’s defenses. A combination of highly effective preparations and deceptions, astutely planned to appear to be training maneuvers, allowed the enemy vast opening-day victories.

In the end, the adversary was roundly defeated, but the cost was horrific; close to 3,000 bereaved families buried their dead and recited Kaddish over their individual plots of grief.

Their 40th yahrtzeit falls on this Yom Kippur, and the IDF is on high alert.

Ambassador Yehuda Avner, writer, who served as an adviser to four prime ministers, is the author of “The Prime Ministers,” (the Toby Press), which is now a major documentary (Moriah Films).

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 476)

Oops! We could not locate your form.