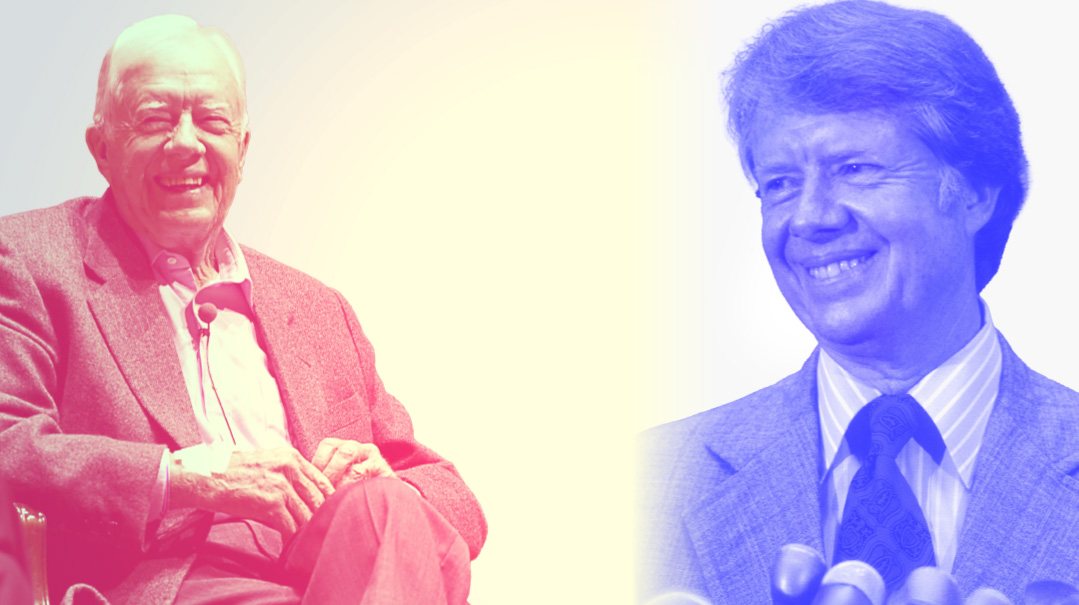

The Two Faces of Jimmy Carter

The toothy, friendly smile belied those steely blue eyes

MYonly encounter with Jimmy Carter occurred in June 1976, just two days before New Jersey’s Democratic primary. By then, Carter had established a commanding lead in the delegate count.

Carter spoke at my old yeshivah high school, JEC in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Our rosh yeshivah, Rav Pinchas Teitz ztz”l, introduced him onstage in the yeshivah’s gym, where three years earlier I would have been playing basketball.

When Carter finished, the crowd gathered around him to shake hands. Carter flashed his trademark toothy smile, appearing friendly. I remember looking into his eyes, which weren’t smiling, and whose steel-blue color revealed more about his personality than his facial expression. While I don’t recall the content of his speech, I must have been impressed. I was finally old enough to vote in 1976 when Carter ran against President Gerald Ford. I do remember pasting a Carter-Mondale bumper sticker on my car and voting for them.

Over the years, other commentators have pointed out the apparent contradiction in Carter’s countenance, which, in a sense, personified his presidency. His cold, calculating style enabled his most significant accomplishment — brokering the 1978 Camp David peace treaty between Israel and Egypt — while his inner struggle to project warmth and empathy led Americans to turn their backs on him.

Carter passed away on Sunday at age 100, after spending much of his last two years in hospice care. His wife of 77 years, Rosalyn, passed away last year at age 96.

The Miller Center, a project at the University of Virginia that provides an in-depth analysis of all US presidents, summarizes Carter’s presidency as follows: “Jimmy Carter’s one-term presidency is remembered for the events that overwhelmed it — inflation, the energy crisis, the war in Afghanistan, and hostages in Iran. After one term in office, voters strongly rejected Jimmy Carter’s honest but gloomy outlook in favor of Ronald Reagan’s telegenic optimism.

“In the past two decades, however, there has been a broader recognition that Carter, despite a lack of experience, confronted several significant problems with steadiness, courage, and idealism. Along with his predecessor, Gerald Ford, Carter deserves credit for restoring balance to the constitutional system after the excesses of the Johnson and Nixon ‘imperial presidency.’ ”

The analysis is fair and balanced. However, Carter’s idealism, especially his wholesale application of human rights as the litmus test for US foreign policy ultimately weakened America. When widespread protests in Iran erupted against the authoritarian and often brutal rule of the Shah of Iran, who nonetheless was an ally of both the US and Israel, Carter pulled his support, forcing the Shah to flee. Carter passively acquiesced as radical Muslims seized power in Iran. The mullahs paid Carter back by seizing 52 American hostages at the US embassy in Tehran, holding them captive for 444 days before releasing them the day Carter left office.

Accusations Against Israel

Carter’s idealism also benefited the Jews, with his support for freedom for Soviet Jewry being another check mark on his plus side.

In the spring 2019 edition of the Jewish Review of Books, Elliot Abrams, a foreign policy advisor to Presidents Reagan and George W. Bush, cited a memoir by Carter aide Stuart Eizenstat that detailed a meeting Carter held in 1977 with Soviet foreign minister Andrei Gromyko. The KGB had just arrested the Soviet Jewish “refusenik” Anatoly Sharansky and charged him with spying for America.

Carter raised Sharansky’s case with Gromyko, who dismissed it as a “microscopic dot” of no importance to anyone. However, the mention must have troubled Gromyko, because after he left the meeting, he turned to Anatoly Dobrynin, Soviet ambassador to the US, and asked: “Who really is Sharansky? Tell me more about him.”

Sharansky languished in prison for nine more years, but the New York Times noted that Soviet Jewish emigration picked up in the middle of Carter’s term. The Soviets granted 29,000 Jews exit visas in 1978 compared to 17,000 in 1977, rising to 51,000 in 1979. The numbers fell to 21,000 in 1980, after Carter imposed a grain embargo on the Soviets following their invasion of Afghanistan.

Carter’s background didn’t naturally lend itself to pro-Jewish tendencies. He attended the Maranatha Baptist Church in his hometown of Plains, Georgia, and taught bible studies in their Sunday school. The church has branches worldwide that recognize the “Hebraic” roots of the Christian church but considers “Jerusalem” as the stumbling block to Arab-Israeli peace, recommends engaging with Islam because of their oil and immigration, and prays for Jews to accept the Christian “messiah.”

The church teachings dripped into Carter’s 1996 book, entitled Palestine: Peace not Apartheid, distorting the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and accusing Israel of being an apartheid state. Rabbi Marvin Hier, founder and dean of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, was outraged. Rabbi Hier had met Carter at a White House ceremony when he presented Wiesenthal with the Congressional Gold Medal, and once the book came out, Rabbi Hier organized a campaign in which some 15,000 Wiesenthal Center members sent letters of protest to Carter’s Atlanta office.

Rabbi Hier said that Carter responded with a curt, handwritten note: “To Rabbi Marvin Hier. I don’t believe that Simon Wiesenthal would have resorted to falsehood and slander to raise funds. Sincerely, Jimmy Carter.”

Rabbi Hier fired back, saying while he doesn’t consider Israel infallible or incapable of errors in judgment, Israel practices self-defense and not apartheid.

A Player Out of Position

Unfortunately, Carter’s apartheid label sticks to Israel to this day, and Carter remained unrepentant.

Ten years ago, at age 90, Carter was interviewed by talk show host Jon Stewart shortly after Islamic terrorists murdered four Jews in a Paris kosher supermarket as part of a revenge attack against a French satirical magazine that ridiculed Islam.

When Stewart asked Carter who was to blame, Carter blamed the victims, not the perpetrators: “Well, one of the origins for it is the Palestinian problem. And this aggravates people who are affiliated in any way with the Arab people who live in the West Bank and Gaza, what they are doing now — what’s being done to them. So I think that’s part of it.”

I once asked Zalman Shoval, a former Israeli ambassador to the US and intimately involved in the Camp David negotiations, to compare the Jimmy Carter he saw, who brokered the Camp David agreements, with the Jimmy Carter who began to express positions blatantly hostile to Israel. What made Carter change?

“I don’t know if he changed,” Shoval said. “I think that Carter deep down had anti-Semitic tendencies, which he tried to put aside.”

It’s not only Jews who didn’t appreciate Carter’s manner of speech. Perhaps his biggest domestic blunder was his 1979 “national malaise” speech. Without using that term, Carter called out Americans for a universal erosion of confidence and self-doubt. Americans want inspiration from their presidents, not mussar, and Carter never reckoned that Americans expected him to show confidence in fighting the spiking oil prices, 15 percent inflation, and the 18 percent interest rates that plagued his term in office.

Ultimately, the Miller Center concluded that Carter was hard-working and conscientious but often seemed like a player out of position.

“There was always, it seemed, something unlucky about him: massive public disaffection with the government, the fires of crisis breaking out at home and abroad, the hostile post-Watergate press, and, by the end of his term, a challenge by a smooth, consummately telegenic challenger [Ronald Reagan] with an engaging new conservative message.”

An Awkward Legacy

By Uri Kaufman

MY grandmother often lamented in her native Yiddish that “the days were long, but the years were short.” The passing of President Jimmy Carter, and the praise heaped upon him for the Camp David Peace Accords, reminded me that people’s memories are often the shortest of all.

In the early days of the Middle East peace process after the 1967 war, the big word was “linkage.” Arab countries refused to even negotiate with Israel, insisting that their dispute with the Jewish state was “linked” to the conflict with the Palestinians; one could not be solved without the other. Since Palestinians refused even to recognize Israel, all diplomacy was a nonstarter.

Anwar Sadat repeated this position in his historic speech to the Knesset in November 1977, saying, “I did not come to you to conclude a separate agreement between Egypt and Israel… It would not be possible to achieve a just and durable peace… in the absence of a just solution to the Palestinian problem.”

Sadat dropped his bombshell four months later, on March 30, 1978, in a meeting with Israeli defense minister Ezer Weizmann. Sadat had no interest in a Palestinian state; he was willing to allow Israeli settlements on the West Bank to remain in place. Weizmann practically fell out of his chair. He later said he was happy Israeli attorney general Aharon Barak was present to hear it, or no one back in Jerusalem would have believed him.

The pathway to peace at last was opened. Except for one major problem: Perhaps Sadat could live without a Palestinian state, but Jimmy Carter could not. He ignored Sadat’s signals and acted like a car out of alignment, constantly swerving off the path into the oncoming traffic of the Palestinian issue.

American diplomat William B. Quandt later wrote that Carter placed himself “in the awkward position of appearing to be more pro-Arab than Sadat, a politically vulnerable position, to say the least.” Being more anti-Israel than an Arab leader is certainly “awkward” for any American president. But for an Arab leader to be less anti-Israel than an American president — well, that’s not just “awkward,” it’s suicidal. On the contrary, Arab leaders need American presidents to give them political cover.

Sadat would get no such cover in Camp David. The talks deadlocked for almost two weeks over the issue of the Palestinians. But Menachem Begin refused to knuckle to Carter’s pressure, and to the astonishment of all, Sadat gave in. His foreign minister angrily resigned. But for Carter, it should have been a moment to savor. He had made history. He had brokered the first Arab-Israeli peace treaty.

Shockingly, amazingly, Carter couldn’t take yes for an answer.

The Camp David Accords, signed on September 17, 1978, were merely a framework agreement. A final peace treaty still had to be hammered out. In the months that followed, Carter never stopped trying to tie everything to a resolution of the Palestinian issue, raising the prominence of the tail until it grew to wag the dog and even threaten to knock it dead.

A stunned New York Times columnist William Safire wrote, “Amazingly, it is not Mr. Sadat who has reintroduced the issue that was successfully finessed at Camp David. The heat to write in the [Palestinians] comes from Mr. Carter, with his born-again ‘comprehensive’ scheme.”

The story has a mostly happy ending. Begin defied Carter, the Palestinian issue was put on ice, and the two parties signed the first Arab-Israeli peace treaty on the White House lawn on March 26, 1979.

I say only mostly, because it was a flawed agreement in one key respect. That flaw was the Jewish settlement of Yamit. The Israelis had built it right where the Sinai Peninsula borders Gaza, in the hope of creating an Israeli-held barrier a few miles wide that would prevent smuggling between the impoverished strip and Sinai. Menachem Begin pleaded with American officials, “emphasizing,” as Jimmy Carter put it in his diary, “that the settlements were important as a buffer between Gaza and Egypt.”

But Carter refused to consider even a land swap, with Israel keeping the Yamit salient sealing off Gaza, while giving Egypt a similar amount of land somewhere else in southern Israel. That blunder casts a shadow over the region to this very day. After Israel withdrew from Gaza in 2005, the Palestinians dug dozens of tunnels into Sinai and smuggled a mountain of weapons inside. We all know what happened after that. Fewer know that after the October 7 attack, Carter condemned Israel and called on the world to recognize Hamas.

This is the legacy of James Earl Carter, 39th president of the United States and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. A commentator remarked on his passing that we are not likely to see another like him. One can only hope that he is correct.

Uri Kaufman is the author of the upcoming American Intifada: How the Left Learned to Hate Israel and Love Hamas (Regnery, 2025).

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1043)

Oops! We could not locate your form.