The Tutsi Link to Sinai

| January 20, 2010As the mythical homeland of the Tutsi people, the Land of Israel still exerts a magical pull for those Tutsis who resisted conversion to Christianity and retained their customs — customs strikingly reminiscent of Judaism

Though he’s comfortably settled in a law practice in Belgium, Matthias Niyonzima’s internal compass still points to two other countries: the African country of Burundi, and the Land of Israel. As his birthplace and the home of his mother and siblings, Burundi still tugs at his heartstrings. As the mythical homeland of the Tutsi people, the Land of Israel still exerts a magical pull for those Tutsis who resisted conversion to Christianity and retained their customs — customs strikingly reminiscent of Judaism. In a riveting interview, Matthias — now known as Matityahu — shares his story with Mishpacha

On a Belgian holiday called Armistice Day, we drive to Brussels to meet Mr. Matthias Niyonzima, or Matityahu Chaim, his more recent name. He lives on a street located in the once very populous area of the “Marolles,” which used to be the poorest and most colorful section of Brussels. Today, the run-down buildings of the past share space with beautiful new buildings. Junky bazaars have made way for shiny and elegant antique stores. Their windows don’t display things that your average Belgian can afford — or would want to have for that matter — but apparently, they have their clientele. Authentic voodoo statues, complete with nails, share space with weird designer furniture. Secondhand vintage stores display eclectic and expensive clothing. A pair of worn-out Chanel shoes is on sale for over a hundred dollars.

We finally reach our destination, Mr. Niyonzima’s law office. His private apartment is located on another floor in the same modern building. Judging by the number of computers, his practice seems to be thriving. For all intents and purposes, it seems a most typical setting for a typical lawyer. But a closer look reveals that not everything is quite so conventional here; the office is decorated with diverse African artifacts — and our gracious host is an observant Jew who traces his roots to the Tutsi tribe of Burundi, Africa.

“Everything Became Clear”

For centuries, the Tutsi tribe was widely regarded as the aristocracy of the African countries of Rwanda and Burundi. The remainder of the population — the Hutu tribe — was seen as lower class. When the Germans and Belgians colonized the area, they singled out the taller and longer-nosed Tutsis as more “European” and therefore naturally fit to serve as the ruling class. Though the tribes got along well before the colonization era, Matityahu remembers growing up with the sense that he was different, and special.

“As Tutsis, we were always different from the surrounding tribes,” he recounts. “Although we didn’t exactly know why it was that way, we knew it was of utmost importance. We had our special customs to which we strictly adhered. In our wildest dreams, we wouldn’t have dreamed that those customs had anything to do with Judaism.”

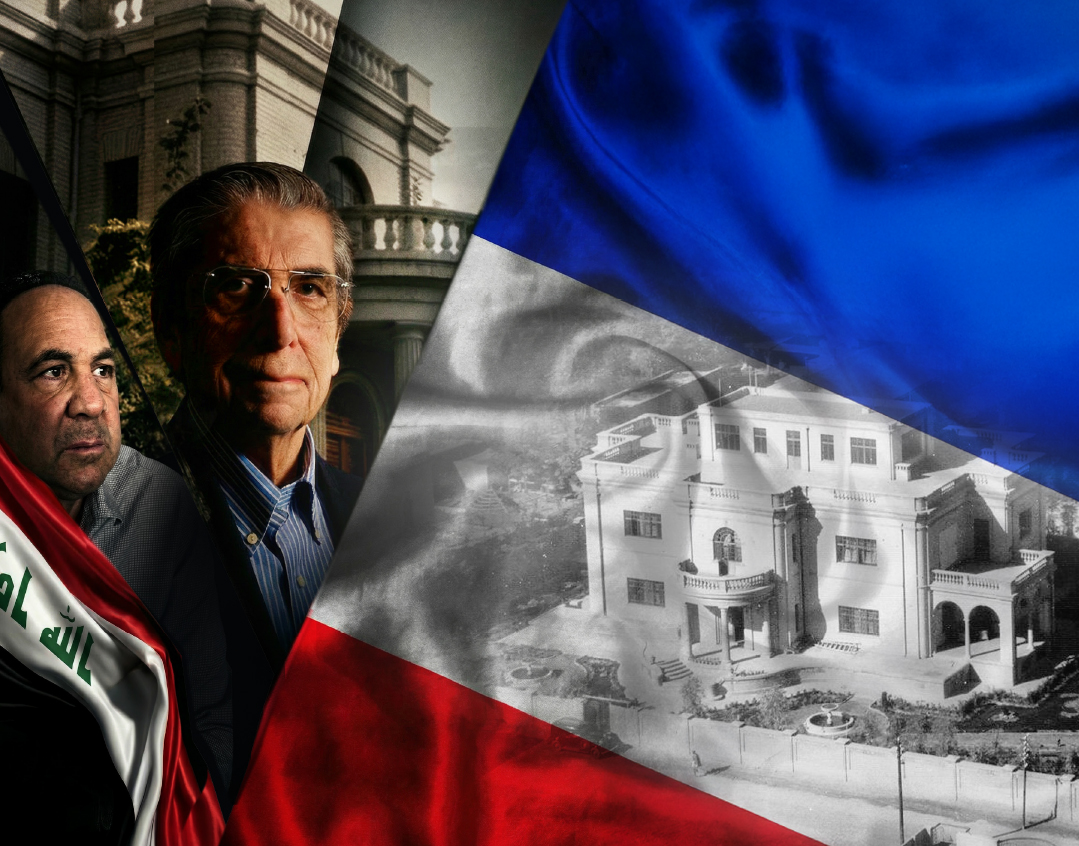

Matityahu never heard of the Jews or their state until 1978, when as a young man he served as organizer of a youth conference in Bujumbura (Burundi’s capital) for youngsters from all over Africa. Among the attendees were some North African Arabs. “When they saw us displaying our Burundi flag, they started to protest and insisted that we remove it, claiming that it was a Zionist flag, because it is adorned with three little Stars of David. That was my first exposure to Israel, and it wasn’t a positive one. Still, it somehow awakened me.”

The bright young man went on to study law in Bujumbura and earned a scholarship to obtain his doctorate in comparative law in the K.U. Leuven, a prestigious Belgian university. During those two years he spent in Belgium, just a stone’s throw from organized Jewish life, he didn’t have the faintest idea of what a Jew was or looked like. Then, in 1985, he ended up in Lausanne, Switzerland.

“It was certainly Hashem’s Hashgachah pratis that placed me with an Italian roommate who was a practicing Jew. He started telling me what it means to be a contemporary Jew and I got the shock of my life.”

All the things that he had always been taught were disgusting, like eating pork or vermin or crustaceans, were forbidden to Jews, as well. Whenever somebody had asked him why he refrained from those foods, he had never been able to respond. All at once, everything had become clear. It was Jewish kashruth.

“When I told my father what I had found out concerning Jewish kashruth, it made him happy beyond belief,” Matityahu remembers. “People had tried to convince my father that in modern times one couldn’t adhere to those ancient customs and that our tribe had to get used to eating everything. But he had stood firm, insisting, ‘If this is what it takes to be civilized, then I don’t want to be civilized.’ He always kept very strictly to the rules.

“In Tutsi tradition, the basics of kashruth were the same as in Judaism, but much stricter. Shechitah meant that the meat had to be slaughtered by somebody from our family or a very close friend. Otherwise, we were not permitted to eat from it.”

When the Tutsis went hunting, it was for protection, not to feed themselves. The meat that was allowed was very limited: for the most part beef, very rarely lamb, no poultry, and no fish.

“There were no major natural water sources around, so we weren’t accustomed to eating fish. When fish later became available, we didn’t know what was permitted. In the back of our minds, we must have felt that certain kinds of fish were prohibited, but we didn’t know which ones. So we refrained from eating all fish.”

After slaughtering the meat, the tribe used to salt it and then pierce it with a large fork, allowing the blood to run down freely. They would then roast it over a big fire and cut it into smaller portions. Although other local tribes ate raw meat, Matityahu’s tribe never did so.

“After eating a slice of meat, you had to wait overnight before you could eat something dairy, and vice versa,” he remembers. “That was really hard, but very strictly adhered to. Dairy products consisted only of cow’s milk and butter, not even goat’s milk. The principle of ‘monitored’ milk was enforced very strictly.

“My father never accepted foreign milk. Once my brother was hospitalized far away, and the nurse wanted to serve him some milk. My father categorically refused. He would not have him drink it. Later, when I told him about the Jews’ adherence to chalav Yisrael, my father was flabbergasted when he heard that people in modern countries were sticking to the same rules that he observed. He would never have believed that a contemporary American would bother to check if his milk had been ‘monitored’ or not.”

The Jewish Connection

The more Matityahu learned about Judaism, the more he was stunned to discover countless similarities between his own traditions and the Torah.

“Umuganuro, the Festival of the Return, was a holiday that the Tutsis observed until 1927, when Christian missionaries brutally abolished it, claiming that it was a pagan inheritance,” he recounts. “It was held in the period of September–October. For the eight days that the festival lasted, we lived in huts outside our regular houses. We never knew why it was called that name or what was its origin, but we knew it was sacred. The missionaries were very well aware that this feast was related to the Jewish Succoth and that’s why they eradicated it.

“When it came to our clothing, as well, we were noticeably different from the surrounding tribes. We always covered our heads, both men and women. I never saw my father with an uncovered head. Boys started to cover their heads when they reached maturity, at age twelve or thirteen. Women only covered their hair after they were married.

“I have a picture of my great-grandfather dressed in some kind of huge ‘tallis.’ The people next to him are servants. On his shoulders he wore ‘tzitzis’ that were knotted in a peculiar way, known only to certain members of the family. They had learned how to knot them, but nothing about their meaning. For us, they represented symbols of Divine connections that had been lost.

“When it comes to circumcision, it was harder to find a link to Judaism,” Matityahu admits. “Though ancient Tutsis probably practiced the custom, that ceased in the early twentieth century. My feeling is that many thought the custom to be drawn from Islam, and so they intentionally stopped it, just to mark the difference. We always have felt that staying different, not melting in with the surrounding tribes, would keep us intellectually alive. Circumcision knew a major revival after 1942, in the colonial times, when the king of Burundi let himself be circumcised. It was after a visit to Ethiopia — perhaps it was under Jewish influence [the Ethiopian monarchy is known to have a strong Jewish identity].

“In general, the king of Burundi had a major affinity for ancient Jewish customs,” Matityahu muses. “When Independence Day was instated, he chose a date that would correspond to Succoth. When the time came to design a new flag, he chose three Stars of David to decorate it.

“One of the most interesting customs of the Tutsi tribe was the special privileged status accorded to the ‘auburn ox’ — reminiscent of the holy status that Jews accord to the parah adumah. Though we never understood why it was considered so outstanding, it was treated with utmost respect and ultimately used for manufacturing objects that served in the courts of kings and princes.

“Another aspect of Tutsi life with a distinctly Jewish feel is the traditional Tutsi courts of justice. The Tutsi courts were known for making peace between conflicting parties. Being a direct descendant of the Burundi kings, my great-grandfather led a court that exercised authority over all the local courts. I remember people approaching my father and asking him to mediate their conflicts. His authority was accepted far and wide.”

For Matityahu, the most dominating feature of all the Tutsi customs was the determination to stay apart. “In my family, as in my wife’s family, we were always talking about a foreign country,” he remembers. “My father told us that our origins were situated in a distant land. Because of that tradition, we were not meant to assimilate with the local population. We had always been strangers in our country, both in our neighbors’ eyes and in our own. We had this very strong feeling that we were somehow unable to integrate into the surrounding society; we felt that we had to keep a distance.”

An Insidious Mission

Matityahu’s memories of his youth contrast starkly with more recent news out of Burundi. The lifestyle sounds almost like a fairy tale. “Our family members were huge highlanders. Most of them were well over two meters (six feet) tall. Years ago we used to live in cabins, which you could describe as large villas, bigger than twenty by thirty meters.” The exteriors of the cabins were braided artistically out of branches; it was incredibly beautiful housing.

At the time, there were still a lot of wild animals surrounding the habitations. “Our main protection was the huge herds of cattle surrounding our estates. These cows were slender specimens with spectacular horns, who could run very fast and were not afraid of the lions. When the lions approached, the cows faced them head-on, and we often witnessed terrible fights.

“This very protection that the herds were offering us also induced members of other tribes to come to work for the Tutsis. Not only was food always readily available; there was also protection from wild animals. And we didn’t enslave anybody! So to escape those regions where they were treated as slaves, they came to us,” Matityahu says, but quickly points out, “still, they were free to leave whenever they chose.”

While Matityahu sees his customs as a source of pride, that attitude has grown increasingly rare among the tribe members. The reason: during the twentieth century, Christian missionaries from Germany and Belgium made it their mission to “educate” the Tutsi tribes. “The missionaries had been brainwashing us for decades that our ancient customs were all of pagan origin,” Matityahu says. He feels that the missionaries were probably aware of the close connection between the Tutsi customs and the Jewish religion, and consciously made an effort to erase that bond.

“The missionaries didn’t even let us keep our names,” he explains his theory. “My real family name is not Niyonzima — which means ‘He who creates life’ — and has been forced upon me by the authorities. My father’s family name, and what should have been mine too, is ‘Ben-Engwe’ [which translates as] ‘Son of the Leopard’ or ‘Mr. Leopard.’ My wife Rachel’s family name is ‘Ben-Mbibe’ or ‘Son of the Frontiers’ (they probably reigned in an area near the border).

“Their idea, of course, was to cut us away from our roots. They knew that the word ‘Ben’ would ultimately lead us back to our Jewish ancestry. My father was thrilled when he realized that I was going back to our roots through Judaism. To him, it was a most gratifying outcome to all those years of Christian threats.”

While the Tutsis made a valiant effort to resist the missionaries’ overtures, the Hutus, for the most part, were willing converts. This was only one element in a toxic brew of conflict that sporadically reached a murderous boil at various junctures throughout the twentieth century. In 1994, the conflict between the Tutsi and Hutu tribes came to a horrific head in a mass murder campaign engineered by Hutu members of the Rwandan government. The rampage resulted in the slaughter of hundreds of thousands (some estimates put the number at one million) of Tutsis at the hands of their Hutu neighbors, in both Rwanda and neighboring Burundi. While most media accounts attributed the tensions to ethnic strife, Matityahu feels that the genocide of the Tutsi people is entirely related to their Jewish origins.

“People wonder why it happened,” he reflects. “There is no logical explanation. It started during the colonial period. Some theorized that Hutu resentment began to fester because the Tutsis held all the power. But even though the German colonizers had originally endorsed Tutsi domination, the Belgians later handed control of the government to the Hutus.

“In 1994, one million Tutsis were massacred in Rwanda in just one month, and 300,000 in Burundi in a week. Their express aim was to annihilate this uncooperative, insubordinate people.

“Many of my uncles, aunts, and cousins were killed. Among my immediate family, most survived. We were living in a central location that was surrounded by a part of the army in which many Tutsis were serving. But my wife’s brother was brutally murdered while both of them were on holiday in another area. When attacked, they ran in opposite directions and he was the one to be killed.”

Does Matityahu seek justice against the killers? He sighs as he contemplates the question. “Practically speaking, there’s really no way to reach justice. If they were to resort to modern courts, we’d need more than 500 years to try every case. There are too many people involved. One million people were killed with simple machetes in such a short time. That means that virtually every person above fourteen was wielding a machete. In World War II, the Germans had specialized forces who were assigned to perpetrate the genocide. Here the whole nation had participated.”

When asked why the Tutsis don’t fear a repeat episode, he shrugs. “Is there a risk that those people will start again? Of course there is. That’s why there has to be economic change, to try and drive the masses away from the genocidal ideology. But that takes years. There are still militias around that are ready to start all over. What you have to understand is that the Tutsis are a warrior tribe. They’re not afraid to fight. They will not run away. It’s not their style.”

Children of Royalty

Matityahu returns to his own personal narrative. “When I met my future wife, I was already well on my way to Judaism. I had seen her in Bujumbura, where she was living with another one of her brothers. Though our families both descend from Tutsi royalty, my wife is of higher descent than me. We all descend from kings and queens, and are considered princes, but she is from recent royalty.

“In keeping with our ancient tradition, I asked my father to approach her father and find out if he was agreeable to the match. My father was overjoyed that I had chosen an acquaintance of the family as my wife. He arrived there with an entire delegation, about thirty people. It was a very special ceremony; I still have the photos. After that episode, my father became ill, so that was his last mission.

“After our wedding, we started to study Judaism together. My wife has also been brought up according to the ancient Tutsi traditions and she was very interested to join me on my journey back to our roots. She had it much easier than me when the time came for us to accept strict Shabbat and kashruth laws. She hadn’t been corrupted by the Western lifestyle like me.

“In the beginning, keeping Shabbat seemed hard to combine with a professional career. I was soon to discover that ultimately, where there’s a will, there’s a way. Hashem’s ways are strange. I was brought to study abroad, far from my family, to discover my roots. At a certain point, I was running a law office together with nonreligious Jewish colleagues. I couldn’t understand why they didn’t keep their traditions. They nicknamed me ‘the bogeyman’ — for always reprimanding them.

“For me, and also for my wife, those ancient traditions from our upbringing in Burundi couldn’t have been anything but Jewish. And following our tribulations, among the various approaches of Judaism, we came to this one conclusion: there was only one thing we could do if we wanted to progress in our Judaic approach — study very seriously and never stop doing so. We also realized that the only proper way to practice Judaism was the Orthodox way. We wanted the real thing — no half measures.”

Though he is comfortably settled in Brussels, and is actually in good company there with a sizable community of Tutsi immigrants, Matityahu still retains strong ties with his relatives back in Burundi.

“My father passed away five years ago, and my mother, currently eighty-four years old, is still living in Burundi, surrounded by my brothers and sisters. All of them derive unparalleled pleasure from my religious quest,” he says, his satisfaction evident. “I regret not having enough time to go back and teach them what I have learned. But they are relieved to have finally understood that their ancestors were worthy people and that they can be proud of their religion and cultural heritage.”

They can now have a good laugh at the endless reproaches they endured at the hands of the missionaries, the taunts about their “pagan” and “barbarian” ancestors. All the efforts to cut them away from their last ties with tradition have failed.

“We all feel victorious to finally be on our way back,” Matityahu concludes with a happy smile.

Jewish Tutsis: A Unique History

The Tutsi history is a fascinating one. Until the European colonization of Africa at the end of the nineteenth century, the roughly twenty-five million Tutsis (or Watutsi, as they were commonly known then) lived in a huge area belonging to greater Ethiopia. When the colonizing nations met in 1885 in Berlin to parcel out the colonial pie, the Tutsi people were stationed in Rwanda, Burundi, East Congo, West Tanzania and South Uganda. After the partition, Emperor Menelik still ruled over Ethiopia, but it consisted of only a fraction of the original area.

Ethiopia has its own unique Jewish history. Until the year 325, the royal Ethiopian family was officially Jewish. The Ethiopians are regarded as the authentic descendants of the union between King Solomon and Queen Sheba, who converted to Judaism, proudly proclaiming “I have left the worship of the sun for the worship of the Creator of the sun.” Later, Coptic Egyptians arrived in Ethiopia and converted them to Christianity by force, and indeed in the year 325 the first Christian emperor took hold of the throne and relocated the capital city (which was situated in today’s Central Sudan) to a city by the Red Sea. Since then, Christians have ruled over Ethiopia. However, the imperial house of Ethiopia has retained its Jewish identity and still honors its Jewish roots. Although the new royal house was officially Christian, they retained many Jewish habits and traditions, and even today the emperor of Ethiopia still calls himself “Prince of Judea.”

All the African people that have Jewish roots originate in Ethiopia. Consequently, the Tutsis claim that even though they emigrated from historic Ethiopia to the region of the Big Lakes, their roots still belong in Ethiopia, a claim substantiated in their oral tradition.

It is generally believed that African names prefixed with “Ben” indicate Jewish origin.

It is important to note that according to some experts, the Falashas, or true Ethiopian Jews, are of the same origin as the Tutsis. The Hebraïzed Tutsis descend from royalty, and throughout their history they remained the upper class. Those who stayed in Ethiopia were relegated to the status of djhymmi, or second-class citizens (which interestingly was also common for Jews and Christians in most Arab countries). However, those who left for other African regions created empires, established courthouses and tribunals, and introduced pure monotheism. During the thirteenth century, many forced conversions to Christianity took place as missionaries tried to annihilate the Jewish identity. This prompted an exodus to Rwanda and Burundi and to Congo and Uganda.

Years later, the Tutsis became a minority when they were joined by thousands of other Africans who came to their lands to escape the enslavement conquests. The Tutsis’ huge herds and large estates offered many employment opportunities to the newcomers as well as the assurance of a steady supply of food, since meat and milk were always available. It must be emphasized, however, that they were never treated as slaves and were free to leave at any time. The areas inhabited by the Tutsis were never colonized, but if they wanted to enter the big cities and centers, the condition was that they be baptized first. The gentiles considered their Jewish customs, such as kashruth, as entirely backward and not suitable for modernized people.

Even today, those Tutsis who seek out their Jewish roots are considered fanatic extremists by local anti-Semites.

FAQ: Looking Toward the Future

Mishpacha asks Matityahu Niyonzima about the options open to those Tutsis still in Burundi.

Q: How do you envision the future of the Tutsis?

A: The ideal solution would be to organize courses in the basics of Judaism for the Tutsis who have remained in Burundi. Kulanu is a Jewish organization that has already begun these classes. It’s not a viable solution to bring all the Tutsis to Israel, as our situation is not identical to that of the Ethiopians. They were not so numerous and faced constant danger, so there was no other choice. The Tutsis don’t really want to leave their country. But it would be necessary for the Jewish world to grant them intellectual and material help on their journey back to their roots. In fact, when we declared in 1999 that we wanted to return to our Jewish sources, some Americans came to our aid very quickly.

Q: Is it really viable for Tutsis to adopt Jewish tradition in Africa? They are going to be even more noticeably different, and that can be dangerous.

A: Yes, it is dangerous — but that is not a reason not to do it. The Jewish People have always had to face all kinds of dangers because of their opinions and different customs. That’s part of the Jewish People’s destiny. On the whole of African territory, Tutsis are a population of about three million. For the moment, moving away is unthinkable. What they need is moral and physical support. They have realized the situation and have already made significant progress. True, they have been persecuted because of their religion under Idi Amin and others. But that is the fate of the Jew: we get persecuted.

Q: In general, does the will exist to return to the dictates of the Torah?

A: There are those who want to go back to the sources, and others who’d rather retain their Christian tradition. The vast majority is in favor of going back, because they seriously seem interested by the discovery of their Jewish background.

It is a fact that the Tutsis’ awareness has been aroused after the genocide. There is a degree of parallelism with the Holocaust. There is this realization that assimilation is not the solution. In the years 1950-1960, many Tutsis allowed mixed marriages, baptism, etc., with the idea that this would mark the end of the persecutions and hostilities.

In 1959, during the Belgian colonization, terrible massacres took place. The Belgians said: It is not our problem. It must be said that the Belgian armed forces were present and that they did nothing to prevent the slaughter.

The traditionalist Tutsis fled in 1959. The assimilated Tutsis stayed, believing that they had nothing to be scared of. And it’s mainly those who were murdered during the last genocide.

In 1994, the assimilated Tutsis were still very recognizable and most of them were mass-murdered. The Belgians had declared that only the extremists who didn’t adapt would have problems; yet it’s precisely the assimilated ones who were killed.

They were told to gather in the churches so as to be spared and were massacred right there. It was a very striking parallel to the Holocaust. In Europe, the assimilated Jews and even those who had converted were murdered just like the others.

The problem with the very few assimilated Jews who remain is that their realization has brought them to complete distress. They understand that their baptism has gained them nothing, but, as they lost all track of their roots, they don’t know where to turn. They are totally lost. They have been baptized for three or four generations.

Then you have those who fled instead of assimilating; they are more traditional. They keep kashruth but don’t necessarily connect their customs to Judaism. They look back, but don’t see Jews behind them.

In our family we are lucky that our parents never cut off our roots, never accepted the idea that our ancestors were pagans or barbarians.

Q: What kind of role does Israel play for the Tutsis?

A: Until 1932, we also had prayers; we’d praise the Almighty with holy verses. All this was banned with such vehemence that it died out. That’s why Israel has become a common denominator, a beacon to hold onto. Those who can retrace their roots focus on Israel, which links them to their past. I traversed the length and breadth of Israel, and every step brought me nearer to the feeling that it was where I belonged. My roots lay there and nowhere else.

For the Tutsis, the presence of the Ethiopians in Israel is a fundamental element. But the situation of the Ethiopian Jews is very different from that of the Tutsis, because during every period of history, they have regularly had Jewish visitors from Israel and elsewhere.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 291)

Oops! We could not locate your form.