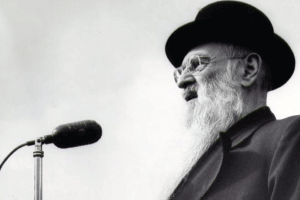

The triumph of Rav Mottel Katz

| December 3, 2014

While destruction rained down on Europe, Rav Mottel Katz and his brother-in-law Rav Elya Meir Bloch were driven to rebuild their yeshivah on American soil — even as their families were decimated in the inferno. Rav Mottel, whose 50th yahrtzeit is this week, didn’t speak a word of English, yet managed to replant black-on-white yeshivah life in a red, white, and blue world

Four long years they lived with the agony of silence. Were their families dead or alive? Ignorance leaves room for hope, but even that glimmer was shattered forever in the winter of 1945 — when in one horrific moment the two roshei yeshivah found out that all had been destroyed. Rav Chaim Mordechai Katz’s wife and ten children, Rav Eliyahu Meir Bloch’s wife and three of his four children — murdered by the Nazis ym”sh beginning on the 20th of Tamuz 5701 (1941). Lesser people might have been paralyzed, permanently shattered. In fact, the co-roshei yeshivah and brothers-in-law did not speak of the tragedy publicly for a year and a half. Their silence was understood by all as an eloquent expression of vayidom Aharon (Vayikra 10:3). They were building Torah in America and hespedim at that time would have been too emotionally disabling. So they waited until the summer of 1946 to speak of their personal cataclysm.

This was the leitmotif of Rosh Yeshivah Rav Mottel Katz, as he was lovingly called by all. And 50 years after his passing on 12 Kislev 5724 (1964), that sense of achrayus — that total devotion to Klal Yisrael regardless of unspeakable personal suffering — still reverberates among the Telshe talmidim whose lives he touched during the years of struggle and growth.

The Early Years

Reb Mottel was only a child when he got his first badge-of-honor nickname — Mottel Populaner — after his father, noted talmid chacham, Reb Yaakov, and his mother, Rochel (nee Hovshas), moved to the village of Populana. When he became a bit older, his parents sent him to the nearby city of Shaduvah, to learn in the yeshivah of the local rav. This would prove to be one of the turning points in Reb Mottel’s life, since that rav was Rav Yosef Leib Bloch, later becoming famous as the Maharil Bloch — who eventually became the rav and rosh yeshivah of Telshe. Even when Reb Mottel’s parents moved to South Africa, he stayed back, electing to remain with his lifelong rebbi, the Maharil Bloch.

When the Maharil’s father-in-law Rav Eliezer Gordon — the rosh yeshivah of Telshe — passed away in 1910, the Maharil moved to Telshe to take his place. Reb Mottel, then a 16-year-old bochur, followed his rebbi, and a few years down the line the Maharil chose him as a son-in-law for his accomplished daughter Perel Leah.

Soon Reb Mottel — a young but highly acclaimed talmid chacham — was giving shiurim to the younger talmidim in Telshe, who all clamored to learn from his wide-ranging knowledge and original thoughts. This endeavor was so successful that the Maharil instituted a four-year mechinah which Reb Mottel headed and taught the highest fourth shiur. In 1921, the Maharil founded a girl’s high school called Yavneh, which was headed at the outset by Reb Mottel himself. The yeshivah then founded a kollel, also under Reb Mottel’s leadership, which produced some of Lithuania’s greatest rabbanim. This early multitasking foreshadowed Reb Mottel’s later incredibly varied responsibilities in both Telshe and the wider Torah world.

At this point, the tragic side of Reb Mottel’s life began. On the seventh of Cheshvan 5630 (1930), Reb Mottel suffered the loss of his rebbi and beloved father-in-law, the Maharil. Soon thereafter, his own father, his beloved Rebbetzin Perel Leah, and their six-year-old son Shmuel also passed away. But instead of crumbling under the pain of crushing bereavement, Reb Mottel redoubled his efforts for Torah. In 5632 (1932), he helped to found the Tzeirei Agudas Yisrael of Lithuania and became deeply involved in the work of the Knessiah Gedolah. He soon married Chaya, the daughter of Rabbi Moshe Kravetz — the rav of Piura and a brother-in-law of the Maharil. Together they were blessed with seven children, in addition to the three remaining children of his first marriage.

Now that much of the yoke of both the spiritual and material wellbeing of the yeshivah was largely resting upon his shoulders, he would travel to America and other locations, including South Africa, to raise funds. Through these efforts, Reb Mottel helped to build up the yeshivah into a fortress of Torah with 380 students.

Unfortunately, those better days were short-lived. In 1940, the Soviet government began confiscating the yeshivah’s buildings for their own use, but Reb Mottel and his brothers-in-law, Reb Avrohom Yitzchak, Reb Elya Meir, and Reb Zalman (the Maharil’s sons) refused to allow the sounds of Torah to cease and heroically kept the yeshivah going.

When the Russians entered Lithuania, the roshei yeshivah and hanahlah decided that emergency efforts must be instituted to save the yeshivah and move it to America. Reb Mottel and Reb Elya Meir Bloch were appointed to this Herculean task. They travelled through an arduous, miraculous route through Siberia and frozen arctic wasteland through Japan, arriving in the United States in the fall of 1941.

Meanwhile, earlier that summer at the end of Sivan, the Nazis overran Telshe, herding all the Jews into horse stables in the forest, where they tormented them horribly for several weeks. Finally they murdered the men in cold blood, including Rav Avraham Yitzchak, his brother Rav Zalman, and virtually all the members of the kollel and yeshivah. The women were spared for another two months; they were taken to the village of Girol, many of them to be brutally murdered on 7 Elul 1941. The remaining few hundred were murdered on 2 Teves 1942.

Starting from Scratch

Little did the two brother-in laws know that all was already lost by the time they arrived on American shores, so they worked mightily to save what they thought was still left in Europe. They contacted Rav Eliezer Silver of Cincinnati, who headed the Vaad Hatzalah and labored valiantly to save every life they could.

Their arrival in America itself began with a miraculous moment, which heralded the incredible siyata d’Shmaya they would later encounter in rebuilding Telshe. Their ship arrived in the port close to Shabbos but they didn’t know a soul and had no idea how or where they would spend Shabbos. Suddenly a man who clearly looked like a religious Jew approached them, inquiring if they needed a place to stay. When they responded that they most certainly did, he accompanied them to a hotel, ushering the two famished, exhausted rabbanim into a room — to a table set with everything they would need for Shabbos. He then promptly disappeared, never to be seen again.

The two roshei yeshivah were physically spent but spiritually invigorated to begin their holy work of rebuilding, and at a kabbalas panim at Penn Station with former Telshe students, they declared courageously that they intended to reconstruct the new Telshe in the glorious image of its best days. Reb Elya Meir and Reb Mottel had many offers to head existing yeshivos, but their burning mission was the revival of their beloved Telshe. There were many offers to begin the nascent yeshivah in New York, where there was already an infrastructure which could support such an institution. But the roshei yeshivah were resolute in their decision to build a mosad where they could also help transform an American city into a makom Torah. Thus Cleveland was chosen for the replanting of Telshe.

This decision raised many eyebrows. First of all, Cleveland was known as a bastion of the Reform movement. Why, many of the locals couldn’t understand, would a backward, primitive school be built amidst what they considered progressive and modern educational institutions? Many of Cleveland’s Orthodox rabbis of the time opposed the idea as well, claiming a bad experience with another yeshivah that had brought machlokes to the city.

Reb Mottel was not deterred, and in one of the first tests of his wisdom and sagacity on new turf, he approached one of the more yeshivishe rabbis in the city, Rabbi Osher HaKohein Katzman. A talmid chacham who had studied in the classic European yeshivos of Slonim, Baranovich, Kletzk, and Mir, Reb Mottel saw in him some hope for courageous leadership.

“Since you are a ben Torah,” Reb Mottel told him, “it’s up to you to break the ice and make an appeal for the new yeshivah. If the balabatim do not agree, then threaten to quit.” Astonished at the audacity yet simplicity of Reb Mottel’s charge, Rabbi Katzman countered that he had only been in Cleveland a short time, was about to get married and that the shul could easily call his bluff and fire him. But the Rosh Yeshivah calmed him down. “I’ve heard you are very popular. Don’t worry, they will not fire you. Meet with them and you will prevail. Besides, for Torah one must have mesirus nefesh.”

After those remarks, Rabbi Katzman was inspired to accept the challenge — and drew in other rabbanim as well. And so the yeshivah opened its doors, beginning with six married men and bochurim who had escaped from the inferno of Europe, plus another six American bochurim from Baltimore.

“Every one of those early moments was amazing,” one prominent Cleveland mechanech who helped pioneer that special group told me. The roshei yeshivah, who couldn’t speak a word of English, somehow understood the needs and issues of American boys. They won them over with their complete dedication 24/7, living with them in the dorm and learning with them all day in the beis medrash. The initial group began learning in the spacious home of Reb Yitzchak Feigenbaum, while Mrs. Feigenbaum z”l personally cooked for the boys and took care of them as she did her own children. After six weeks, the Feigenbaums moved to a smaller house, selling their home to the yeshivah.

In those days, Reb Elya Meir and Reb Mottel did whatever was necessary to keep the yeshivah financially afloat. They would stand outside the supermarkets, spot a Jewish woman, and ask for her change. The roshei yeshivah themselves subsisted on ten dollars a week salary, a paltry sum even in those days.

Six months after the yeshivah’s founding, having outgrown the Feigenbaum home, Rav Mottel and Rav Elya Meir decided to purchase their own building. Rav Eliezer Silver came from Cincinnati to celebrate with them and the roshei yeshivah spoke eloquently, their words a mix of joy and fear of the as yet unknown fate of their families and talmidim left behind.

Within three years, the yeshivah had over 100 talmidim, and the crush of new students forced the purchase of a bigger building. The celebration took place on the 18th of Kislev, 1945, just a few weeks before they heard the horrific news of the complete destruction of Telshe and the grisly fate of their families. Ironically at this joyous occasion, many speakers committed themselves to do all that they could to save what they thought were the remnants of the yeshiva and community. Little did they know that the carnage had been total.

The deep founts of spiritual strength Reb Mottel drew upon allowed his greatness to shine forth through the bleakest darkness experienced by our people. Reb Mottel showed himself to be the multifaceted giant which the new circumstances required. He took personal responsibility for his extended family, helping his nieces, nephews, and the other new arrivals from Europe find appropriate shidduchim, jobs, and ways to rebuild their shattered lives — while nurturing every talmid so that each one knew that Reb Mottel cared completely for his well-being.

Following the shattering news that his wife and ten children had been murdered, on Lag B’omer of 1946 the Rosh Yeshivah, with great gevurah, set forth to rebuild his family, marrying Esther Mindel Mandel (who passed away this past Chol Hamoed Succos). They were blessed with two boys and a girl.

Rav Elya Meir Bloch (whose one surviving daughter Chasya married Rav Eliezer Sorotzkin) also remarried, and in the few years before he passed away, his wife Nechama bore him another son and daughter.

Forging Ahead in Cleveland

As the yeshivah grew, the ever-resilient roshei yeshivah felt it imperative to create a secluded and protected environment for the bochurim to grow in Torah without the distractions of city life. They therefore purchased a 60-acre campus in the Cleveland suburb of Wickliffe, which eventually boasted batei medrash, offices, dormitories, lunchrooms, a pool, large gym, and whatever else was needed for a yeshivah of American bochurim to function. These amenities were unheard of at the time and reflected the far-seeing eyes of the prescient roshei yeshivah.

Yet one of the roshei yeshivah didn’t live to see the fruits of this new frontier. On 28 Kislev, 1954, Klal Yisrael, Telshe and particularly Reb Mottel himself suffered the great loss of the beloved Rosh Yeshivah Reb Eliyahu Meir Bloch ztz”l. He was 60 years old. For Reb Mottel, this wasn’t just the loss of his best friend, brother-in-law, and partner, but also left him alone to shoulder the burden of the yeshivah.

In his moving letter of condolence, my own rebbi, Rav Yitzchok Hutner ztz”l, invoked the departure of Eliyahu Hanavi from this world. “Chazal promised,” he wrote, “that the righteous are greater in death even than they were in life. Therefore… the mantle of greatness which fell from the shoulders of the fallen Rosh Yeshivah will surely through your leadership cause a double portion of spiritual success to descend onto the yeshivah.” Indeed, as always, Reb Mottel rose to the challenge, somehow finding new strength and the youthful energy to accomplish ever more each and every day.

Reb Mottel ran the yeshivah, gave shiurim, and somehow managed to know every bochur and his particular needs. He was the lifeblood of the mechinah, kollel, and chairman of the Vaad Hachinuch of the Hebrew Academy and Yavneh Seminary. Although the Rosh Yeshivah had been gone for many years when I was a member of the Vaad Hachinuch in my years as a rav in Cleveland, I felt his presence in all that we decided. Everything was implicitly done with the thought of “What would the Rosh Yeshivah have said?” One prominent leader of the Hebrew Academy remembers Reb Elya Meir and Reb Mottel’s response to a controversy about enrollment. Should a child from a nonreligious home be accepted? The two brothers-in-law responded almost simultaneously “mun darf rateven Yiddishe kinder — we must save Jewish children.”

But the Rosh Yeshivah was not satisfied with having replanted Telshe in Cleveland. He sought to widen his net by spreading Torah in Minneapolis and, together with Reb Elya Meir and Reb Aharon Kotler, in Boston. Perhaps his most lasting creation, outside of the Cleveland yeshivah, was the founding of Telshe Chicago. In Elul of 1960, the Rosh Yeshivah traveled to Chicago with two of his trusted close talmidim, Rav Avrohom Chaim Levine shlita and Rav Chaim Schmelczer ztz”l (Rav Chaim Dov Keller joined a bit later) to spread Torah the Telsher way.

One of the further tragedies which the Rosh Yeshivah endured was the catastrophic fire in one of the dormitories on the 5th of Teves 5723, January 1, 1963. Two boys in the room most engulfed in flames jumped to their rescue with minor injuries, but another two perished in the conflagration. Despite the profound aveilus which overwhelmed the yeshivah, Reb Mottel refused to bow to the pressure to temporarily close the yeshivah and send the bochurim home. He somehow found room for 300 boys to sleep, energized the yeshivah’s sedorim, and to the shock of many, announced a million-dollar campaign to rebuild. In the process, the Rosh Yeshivah managed to build room for over 400, adding a mikveh primarily for the chassidic bochurim who began streaming to the yeshivah.

Chinuch for a New World

The Rosh Yeshivah’s personality and hashkafos were imprinted on every decision made in the yeshivah and its extended branches. He was a man of absolute punctuality and valued the importance and uniqueness of every second — he had no tolerance for laziness or waste. When one major American rosh yeshivah passed away, many felt that Telshe should shut down and travel to New York for the funeral. Reb Mottel, however, decreed pithily, “one bus is kavod haTorah, two is bittul Torah.”

Yet on the other hand, he had a keen understanding of the American bochur and the need to keep him interested and involved. (Rav Aharon Kotler referred to him as “the rosh yeshivah of the American generation.”)

The Rosh Yeshivah instituted bechinos (oral exams) four times a year, periodically testing a class on his own when he felt it was necessary. When he gave one of these bechinos, he never embarrassed a boy who was struggling. On the contrary, he helped the bochur to formulate an original answer which the boy would later proudly call his own. If a boy did not even seem to understand the question, Reb Mottel would congenially discuss the entire sugya with him, to the point that he now was easily able to answer all the questions. Although Reb Mottel usually remained for the discussions resulting in the assigning of a grade, when it came to his own son, he would leave the room so that the other Ramim could discuss his progress objectively.

The Rosh Yeshivah also stopped in periodically to test the boys in the Hebrew Academy. These visits left an indelible impact upon the young talmidim, but one time, even the best boy in the class could not seem to give any answers. He just stared at the Rosh Yeshivah and kept silent. Finally, the rebbi whispered to him, “Is everything okay? Usually you can answer all these questions easily.” The youngster looked at his rebbi in surprise. “Rebbi, if you met Eliyahu Hanavi, would you be able to just talk to him?” The rebbi tried to reassure his student — “He is indeed a gadol, but he’s not Eliyahu Hanavi. Don’t worry so much.” The astute student had the final word. “Rebbi, to you he may not be Eliyahu Hanavi, but to me he is!”

Reb Mottel’s integrity wasn’t just a lesson to the bochurim — he applied it to himself as well. One day, the maggid shiur for a Mishnah Berurah class didn’t arrive, and the Rosh Yeshivah arose to substitute. Realizing that he was not fully ready to give the shiur to his own satisfaction, he promptly sat down. The Rosh Yeshivah announced in a lesson his listeners would always remember, “One should never give a shiur to the tzibbur without being fully prepared.”

Every decision he made was nuanced and thoroughly calculated. In the early 1940s, when a request was submitted to daven Maariv early for just one day because a major sports game was being played that day and some bochurim wished to listen on the radio, he acquiesced. In later years, such a request would have been laughed off by the yeshivah administration, if it would even have been submitted at all. But in those early years of building Torah on the arid soil of the New World, a true leader had to distinguish between a hora’as sha’ah — a temporary determination — and what would later become fixed policy.

Another example of the Rosh Yeshivah’s profound understanding of the new American landscape related to Mother’s Day. Although in Torah circles, this day is not quite recognized or celebrated, Reb Mottel urged a number of boys to call their mothers to express their best wishes. He was concerned that American mothers, who were accustomed to commemorating such a day, would view the lack of a call or card as an implicit statement that the Torah does not value or appreciate mothers.

Once the Rosh Yeshivah called in a recent arrival from Morocco to speak to him in learning. Strangely, the Rosh Yeshivah began the conversation by asking to see the young man’s wallet. Noting that it contained only a dollar or two, Reb Mottel put in $20 (a significant sum in those days), declaring “now we can talk in learning with some peace of mind.”

It sometimes gets cold and slippery in the Cleveland winters. The Rosh Yeshivah asked a talmid with whom he was walking if he could hold on. However, the talmid soon realized that while the Rosh Yeshivah was walking just fine, it was he, the New Yorker, who was saved from falling on the ice by the much older Rosh Yeshivah. Reb Mottel, though, would never hint that the young man required assistance.

And although Reb Mottel was ever-sensitive to the nefesh of an American bochur, he drew the line at the expense of personal dignity. The Rosh Yeshivah urged that all the talmidim reflect this ideal, and insisted that they wear hats and jackets whenever they ventured off the campus. Even when they brought their clothing to the laundry, he exhorted them to carry everything in a suitcase, as befitting a ben Torah, instead of over their shoulders in a sack. The Rosh Yeshivah’s profound sense of dignity imprinted itself upon the talmidim, creating a Telsher brand which bespoke kavod habrios at all times.

Although the Rosh Yeshivah rarely spoke of his lost children and family, he did so when it would help someone else. When one of his close talmidim lost a child, Reb Mottel arrived to be menachem aveil and whispered “lamir beide veinen — let us both cry, I know your heart is bitter,” and then poured out his own tears with those of the bereaved young father. This prominent Torah personality told me that the Rosh Yeshivah’s comforting was what restored his ability to function thereafter.

Final Words

On the last Shabbos of his life, the Rosh Yeshivah spoke to the heart of a bochur, delivering a message which was eternal. Reb Mottel was giving a vaad (Mussar discourse) on Chovos Halevavos, pointing out that one could learn a great deal from studying plants. Despite the fact that from moment to moment one does not notice growth, over an extended period one can recognize the change. When he was finished, he called over a boy who was deep in thought and lovingly explained. “This is true of spiritual growth as well. It is sometimes hard to notice the growth from day to day but in the long run, one has grown tremendously.” The following Tuesday the Rosh Yeshivah was gone, but the talmid realized that Reb Mottel was speaking directly to him. He had been despairing of achieving significant growth, let alone greatness, but the Rosh Yeshivah understood and gave him a profound insight which has stayed with him for life.

Even after a devastating heart attack, Reb Mottel managed to function with minimal heart muscle, heroically continuing his avodas hakodesh each day he had left. On the 11th of Kislev 5725 (1964), the day before his passing, he wrote an important communal letter to Rav Itche Meir Levine, head of Agudas Israel and even went to the beis medrash. He later suffered two heart attacks and passed away suddenly, to the shock of the Torah world at large. Yet in the half century since, his legacy has only grown and the Torah empire he left behind continues to shine. His son, Rav Yankel Velvel, has virtually turned the city of Beachwood, Ohio into a makom Torah and his other children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren continue in his derech, in the spirit of Telshe.

With thanks to Rav Shaul Dollinger (Rosh Yeshivah Pri Etz Chaim, Ashdod); Rav Moshe Mendel Glustein (Rosh Yeshivah Yeshivah Gedolah D’Montreal); Rav Aharon Dovid Goldberg (Rosh Yeshivah Telshe Cleveland); Rav Binyomin Grunwald (maggid shiur, Cleveland); Rav Yaakov Zev Katz (Rosh Kollel Yad Chaim Mordechai, Beachwood, Ohio, son of Reb Mottel); Rav Moshe Kravetz (mechanech, Lakewood); Rav Avrohom Chaim Levine (Rosh Yeshivah Telshe Chicago); Rav Shlomo Mandel (Rosh Yeshivah Yeshivah of Brooklyn); Rav Yitzchok Scheinerman (mechanech, Cleveland); and Mr. Ivan Soclof (former president, Hebrew Academy of Cleveland).

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 537)

Oops! We could not locate your form.