The Story That Never Grows Old

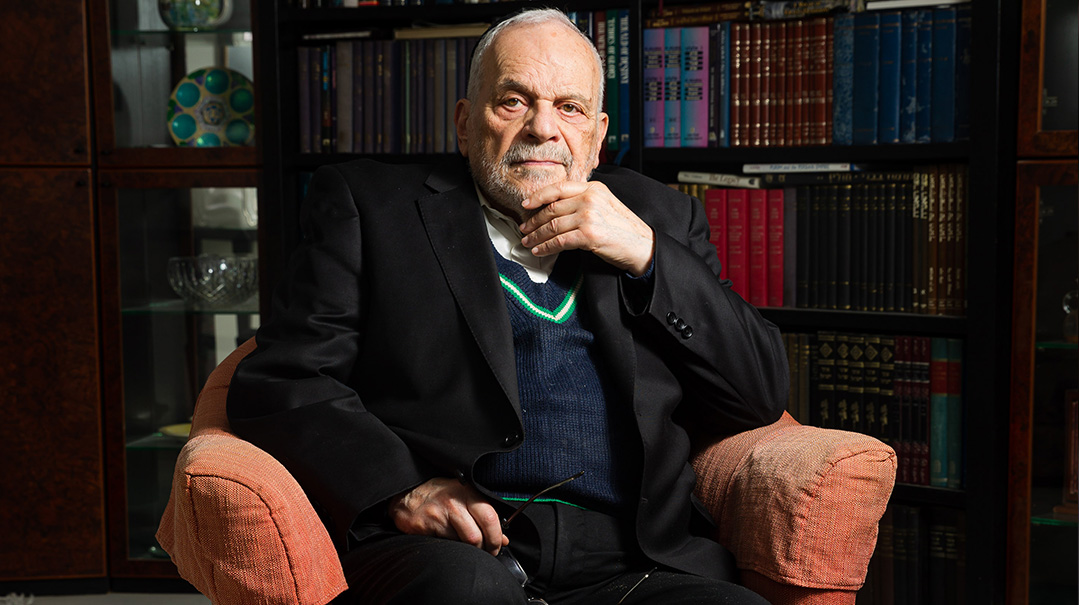

Rabbi Berel Wein has an unquenchable love for the greatest saga of all time: the survival of his people

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Family archives

I

have discovered the perfect cure for anyone who finds fast days difficult: Sit down with Rabbi Berel Wein for as many hours as you want, and let him take you on a panoramic tour ranging from Jewish history to the current scene. I can guarantee that you will soon forget about the fast entirely, and the hours will roll by. I know because that is how I spent several hours this past Taanis Esther seated with Rabbi Wein at his living room table.

Both Rabbi Wein and I would identify ourselves as Chicago natives, though there is a difference, as Rabbi Wein himself once pointed out. Over 15 years ago, I had the honor of introducing him at a pre-Rosh Hashanah program at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall, and I noted that though his “Chicago accent” is world famous, through over 1,200 recorded tapes, I don’t recognize it as the same as mine.

Rabbi Wein replied, “Jonathan isn’t from Chicago He’s from the suburbs.”

As we talked, inter alia, about what a wonderful place Chicago was to grow up in, I realized how much wisdom was contained in the remark. Rabbi Wein lingered over each of the old litvishe rabbanim under whom he studied, including his maternal grandfather Rabbi Chaim Zev HaLevi Rubenstein, who was one of the founders of Hebrew Theological College, the first yeshivah in the Midwest; Rav Mendel Kaplan; Rav Chaim Kreiswirth; Rav Mordechai Rogoff; and his father, Rav Zev Wein. He is still nostalgic for the old West Side, from which all the Jews fled over a period of four years, with only six (two of which became “traditional” — i.e., separate seating but no mechitzah) of the 42 shuls that had dotted the neighborhood successfully moving to new neighborhoods. In short, Rabbi Wein lives with a sense of place that no suburban kid carries with him.

Rabbi Wein even knows more about my maternal grandfather, Maxwell Abbell, the most prominent Chicago lay leader in his youth, than I do. (I was five when he passed away.)

“You would not find a lay leader like him today,” he tells me, “who, despite not being fully observant, was totally committed to both the physical and spiritual survival of the Jewish People, aware that an intense Jewish education is the key to that survival, and who served on the board of Hebrew Theological College [Beis Medrash L’Torah].”

The occasion of our conversation was the publication of Rabbi Wein’s new book Struggles, Challenges, and Tradition: How Jewish Communities Defended Orthodoxy 1820–1940 (ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications), which served as a jumping off point for numerous other topics as well.

Rabbi Wein with a grandson laying tefillin for the first time. “Historically, communities only flourish when there’s a strong core of Torah”

Still Going Strong

The first time I called to make this appointment, your secretary said that you were in the midst of a fundraising campaign for your Destiny Foundation. So I gather that you have multiple new projects on the horizon.

Rabbi Wein: Yes. We have a new film on Don Isaac Abarbanel that is 90 percent complete, and for which I was very involved with the screenplay. Most of what we know about Abarbanel is secondhand. But in the midst of his commentary on Shoftim, he veers off into a lengthy retrospective on his fascinating life, in which he served as the chief financial advisor to the royal family of Portugal and subsequently that of Spain. He wrote his commentary on Shoftim after he was already in Italy advising the king of Naples. There is a discernable bitterness to his retrospective look at his life, in particular that he had used his great talents in the service of two monarchies, which despite his service had expelled their Jewish populations.

I’m also working on a commentary on Malchuyos, Zichronos, and Shofros. And the Jewish Destiny Foundation is making a film on the tumultuous period in modern Jewish history between the Six-Day War in 1967 and the Yom Kippur War of 1973.

Oops! We could not locate your form.