The Shovels

| November 16, 2021Somewhat rusted but totally functional, the shovels found their meaning in assisting in kevuras Yisrael

I run a tool gemach.

Ever since I was a little kid in the bungalow colony, we were always building something. Old carriage wheels, loose boards, and rusty nails were all we needed to construct a go-cart. Home Depot? Better than any museum. I could spend hours going up and down the aisles just gawking at the array of gizmos we could use to build and fix things. One of my mottos is, “Why hire someone else when you can do it yourself (and save money)?”

The idea to launch a formal tool gemach in my neighborhood was the brainstorm of my friend and fellow rebbi — Rabbi Yehudah Mayerfeld. He established the Monsey tool gemach a number of years ago as an extension of his inclination toward DIY (do it yourself). When we would meet in the teachers’ room for a short breakfast, we often found ourselves sharing our most recent home improvement projects.

It wasn’t long before he urged me to start a similar tool gemach in Far Rockaway. I initially balked, as I simply didn’t have the room for more than the stash of tools I already possessed. Besides, I was already becoming an unofficial tool gemach, as the neighbors learned that my existing tools were always available for them. My resistance broke down when Yehudah offered to pay for the initial additional items to stock a real tool gemach. So it became official. The most common tool request, aside from the regular screwdrivers, hammers, and pliers, would have to be the pole-extending tree pruner around Succos time. Although not quite a tool, our bicycle pump has made our house the official pumping station for bikes and basketballs on the block.

I have had some really interesting requests — jackhammer?! I was afraid to ask what it was needed for. (We don’t have one!) Pick-axe to bury the pet bird?! (Yes, we do have one).

The gemach affords me the opportunity to find likeminded DIYers in the neighborhood. Quite a few big talmidei chachamim are part of the club. One new caller once wanted to come over to see what he could take. I had to explain that the tool gemach is for lending, not for keeping. On occasion I’ve had to field calls from people wishing to donate their old tools, mostly from children disposing of their parents’ estates. Unfortunately I have no real use for rusty saws or ancient hand-pushed lawn mowers. (I have bad memories as a teenager of using this on the hill in my parents’ front yard.) Maybe I should have these potential donors get in touch with the one who wants to take my tools. Besides, the limited space that I have in my shed precludes the growth of a bigger gemach.

So I was annoyed one day to find a batch of shovels and spades leaning on the side of my house. My guess is that someone assumed I could use them for the gemach and just left them. But room in my shed was at a premium, so they just sat there outside. For a few years. Occasionally, I would look at them and think that I should just throw them out, but procrastination got the better of me, and there they remained.

When Covid struck, the borrowing slowed down a bit, but went somewhat unnoticed by us, as we were busy dealing with complications with my father-in-law’s health. My in-laws — Bubby (Elli) and Zeidy (Ed) Epstein, both nonagenarians, were still living in the Asbury Park area where my wife had grown up.

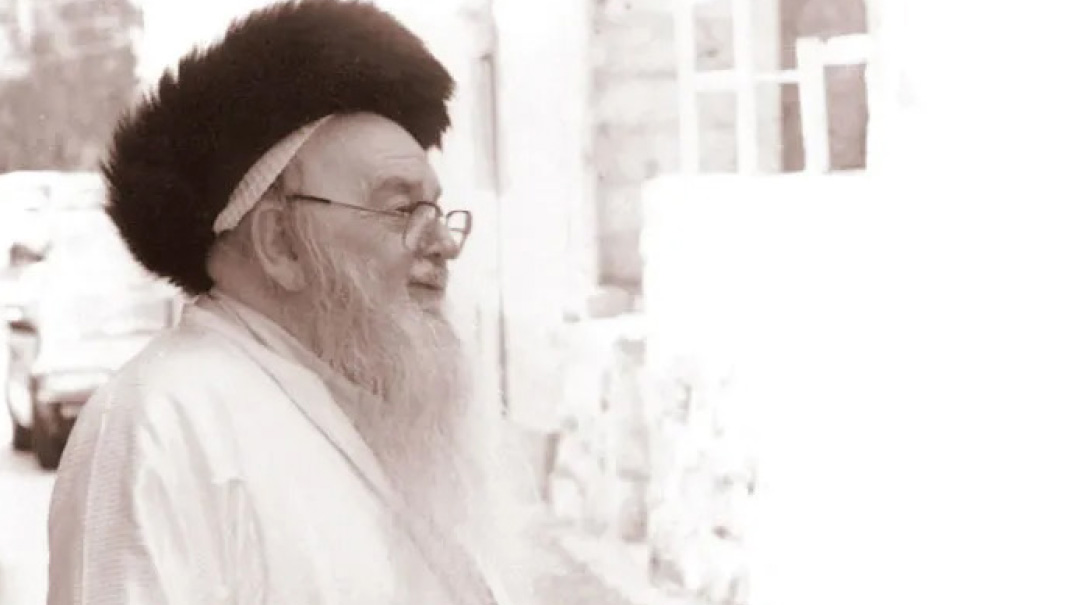

Zeidy was able to retire at an early age from a government job at nearby Fort Monmouth and spend his days increasing his Torah knowledge that was lacking from his childhood years. Barely ever missing a minyan, Zeidy became a regular at the after-davening shiurim from the nearby Deal-area shuls. At home it became the norm to see Zeidy washing the dishes while listening to Rav Avigdor Miller z”l, and poring through the Midrash to find questions to ask at the Shabbos table.

Bubby would also frequent many of the local shiurim for women. The constant in Bubby’s life was her weekly visit on Erev Shabbos to the Jersey Shore Medical Center, a hospital servicing the Shore and nearby Lakewood, to be mevaker cholim with the Jewish patients. Originally, a few women from the Asbury Park Shul, prompted by Rabbi Yosef Carlebach, would make the visit and bring flowers and good Shabbos wishes to the Jewish patients. In time, Bubby remained the sole volunteer and became known as “the flower lady,” to both patients and hospital staff. She was able to continue this chesed venture for three decades until Covid struck.

Zeidy’s overall health had been deteriorating for a number of years, and hospital stays at Jersey Shore were becoming the norm. On a number of occasions during the Covid pandemic, he had to be rushed to the hospital for treatment of various ailments. Despite Bubby’s celebrity status at the hospital, Zeidy, also suffering from hearing loss, was often left alone and disoriented during the pandemic days, as visitations to the hospital were curtailed and sometimes nonexistent during the pandemic.

When the call came on a late Thursday night shortly after Succos last year that Zeidy had returned his neshamah to Hashem, my brother-in-law Aaron sprang into action to try to arrange the kevurah for Erev Shabbos. Persistence and resolve were effective in moving the kevurah from the only available slot at 2 p.m. to a 1 p.m. graveside levayah on an early Erev Shabbos. At least grandchildren and great-grandchildren from out of town would be able to make it on time. Zeidy, a simple and humble person, seemed to have planned a scenario in which there would be no more than a few people and few words spoken at the graveside service. I had thought that at least it would be fitting for Zeidy’s family to handle the actual kevurah.

Friday morning we were informed by my brother-in-law that the cemetery administration had very clear Covid guidelines limiting the assistance of anyone other than cemetery workers in the burial. In fact, we were told that everyone would have to remain in their cars until the burial was finished by the workers. I was overcome with disbelief that Zeidy would have no one Jewish involved in the actual burial. Since my youth, I had been involved in numerous funerals where all aspects of the kevurah were handled only by Yidden.

It was my good fortune to have been raised in the Young Israel of Queens Valley under the guidance of Rav Peretz Steinberg shlita. Rav Steinberg had organized a chevra kaddisha for the shul through which the members took care of all the needs from shemirah, taharah, kevurah, and nichum aveilim. The youth were encouraged to participate as well. One of the shul members, Haskel Yadlovker, while not a formal educator, nevertheless took the role of instructing us youth at a kevurah in the various tasks and how to perform them. He had the foresight to understand that our generation would have to lead in this area one day. With this ingrained in my approach to any kevurah, I could not fathom Zeidy being denied this kavod.

A call to the cemetery confirmed that the rules were to be strictly adhered to. Not willing to give up, I persisted in my questioning.

“If the workers step aside more than six feet away, could we lower the aron into the ground?” I asked.

“Sorry, these are the rules.”

“Could we at least fill in the kever with dirt?”

“No — I’m sorry.”

I was still searching for some way to get a little concession, but I saw that they were resolute and not budging.

And then I had a flash of inspiration.

“What if we bring our own shovels?” I asked.

Slight pause, maybe a foot in the door.

“Hold on and I’ll find out.” After a few moments on hold, the answer was given affirmatively — “Yes, if you bring your own shovels, you can fill in the grave.”

And suddenly the shovels that had taken up permanent residence on the side of my house had a purpose. Somewhat rusted but totally functional, the shovels found their meaning in assisting in kevuras Yisrael. Three generations of descendants were able to give Zeidy the final kavod he deserved.

The Gemara, in Taanis 21b, relates an incident in which the city of Sura was besieged by a plague, yet the neighborhood of Rav was spared. Although Rav himself had great enough merit to save his neighborhood, we are told that the merit of salvation was due to an individual who lent out shovels and spades for burial. Rashi points out that this merit was based on the concept of middah k’neged middah.

While my shovels had not been designated specifically for burial, perhaps the all-around merit of gemilas chasadim evoked a middah k’neged middah to arrange for them to be used in this greatest chesed. —

Rabbi Aharon Friedler has been a rebbi at Hebrew Academy of Nassau County in Uniondale, New York, for three decades. He lives in Far Rockaway, New York.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 886)

Oops! We could not locate your form.