THE SACRED WORLD OF THE SKOLYA REBBE

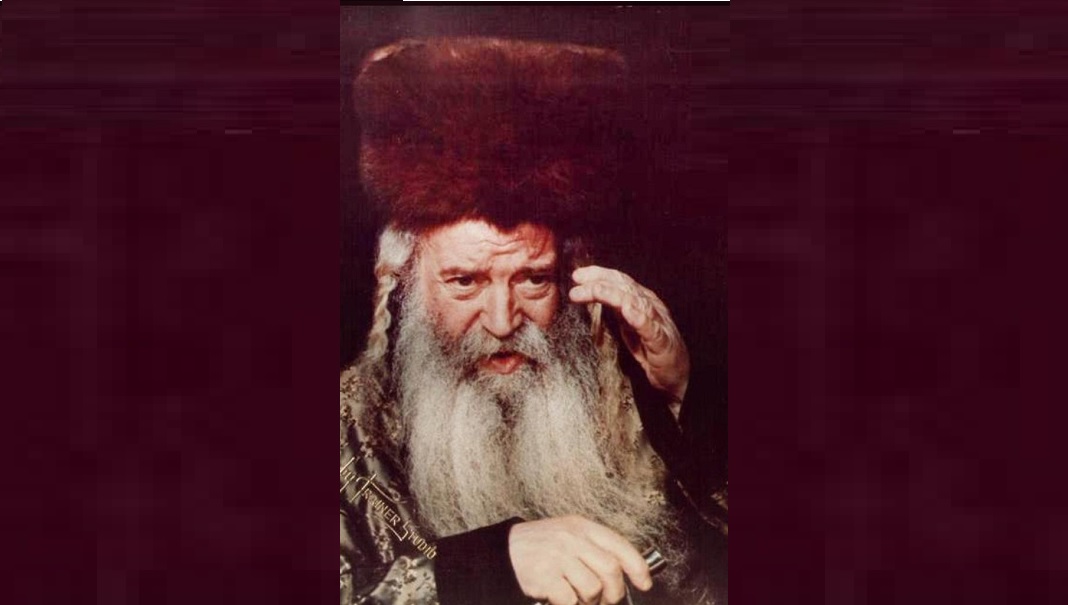

An appreciation of Rav Dovid Yitzchok Eizek of Skolya, Ztz”l, on his thirtieth yahrtzeit

The story of his life seems more fitting for a tzaddik who lived centuries ago, so removed was he from the mundane events of the American scene. Yet Rav Dovid Yitzchok Eizek of Skolya reached those lofty heights from a small room in twentieth-century Williamsburg. He rarely ventured out of his home but still won many admirers – even among litvishe scholars. As his grandsons mark thirty years since his passing, they share their memories with Yisroel Besser, painting a picture of a man entirely occupied with otherworldly spheres

When we were young, a favorite pastime was collecting and exchanging pictures of gedolim. The value of any given picture was defined primarily by beard color or length, or perhaps a colorful prop; we knew very little about the actual spiritual heights of the giants whose images we worked so hard to accumulate.

One picture came with a story too thrilling to be real; it was retold in reverential whispers. As I said, we were unable to see the Torah knowledge or fear of Heaven in these luminous faces, but the “shin” was something we could all see. Right there on the Rebbe’s forehead, clear as day, three vertical creases formed the letter “shin,” representing something surreal, sacred — some sort of Divine stamp.

That was my childish introduction to the saintly Rav Dovid Yitzchok Eizek, Rebbe of Skolya.

From Earlier Generations

As we grew older, we began to hear the most fantastic tales about this angelic soul, stories more suited to Mezibuzh of 250 years ago than to the Brooklyn of this century. The Skolya Rebbe never really came to America at all, though he resided here for decades. He never founded mosdos or built a Chassidus; he worked in a hidden realm. In addition to being brilliant, he also a master of Kabbalah, inhabiting a secret, candlelit world of tikkun neshamos, giluyim, and Sheimos.

Students close to Rav Moshe Feinstein recall how he even this great masmid envied Rav Dovid Yitzchok Eizek’s extraordinary diligence. Reb Moshe grew acquainted with the Rebbe in New Hampshire, where they had both vacationed one summer. After meeting him, Reb Moshe began sending some of his teshuvos to Rav Dovid Yitzchok Eizek for review, so impressed was he by the Rebbe’s knowledge and acuity.

That’s the way it was with the Rebbe; whoever met him became his chassid immediately. Talmidei chachamim were taken by his command of the revealed Torah, and mekubalim were astonished at his proficiency in the hidden Torah.

Yet Rav Dovid Yitzchok Eizek preferred to remain at home, above his beis medrash, cloistered in his own four amos. He rarely stepped out, reluctant as he was to walk the American streets. In fact, during his Williamsburg years, his family and chassidim wouldn’t build a mikveh in his building, for his daily walk to the mikveh across the street was the only time he enjoyed fresh air.

During summers in the solitude of the country, Rav Dovid Yitzchok Eizek would walk outdoors, but even then it was with a disclaimer: “It’s a mitzvah to listen to the chachamim,” he would say, “and the Kopycznitzer Rebbe told me I must walk more.”

Rav Dovid Yitzchok Eizek shied away from accepting an active role in the wider Jewish community and wouldn’t look at newspapers — even Jewish ones — refusing so much as to touch them with his hand. During the early 1940s, when every piece of news from Europe was crucial, the Stoliner Rebbe, Reb Yaakov Chaim (known as “the Detroiter”), would update him each day. Behind closed doors, the two Rebbes pondered the latest events, using a language only they understood.

A hidden soul, content to serve Hashem in his own secret realm.

Those who knew about it knew. Those who didn’t were all the poorer.

A Lofty Plane

Rav Dovid Yitzchok Eizek always seemed to be learning.

Each evening, his son Reb Boruch would visit him, and the reception was always the same. The Rebbe would look up from his Gemara and indicate where he was holding. He wouldn’t stop in the middle of a sugya, but had too much derech eretz to ignore his visitor. So he would point to the next “two dots” as if to ask his son’s permission to finish the section. Only after completing it would he welcome Reb Boruch warmly.

A certain taxi driver worked the night shift, cruising the desolate New York City streets in search of passengers. He knew it was time for him to go to sleep when the Skolya Rebbe’s window finally grew dark, which was never earlier than three a.m. and usually closer to four.

When did the new day start? Those who learned together early in the morning in the Skolya beis medrash would greet the Rebbe as he made his way to the mikveh at five a.m.

One morning, the Rebbe stepped into the beis medrash at five with an anxious look on his face. He surveyed the assembled and inquired after Reb Yosef Tennenbaum, who taught in the beis medrash and was a regular in the early-morning study group.

The others replied that he hadn’t come that day.

The Rebbe turned ashen. “He asked me a kushyah in my dream, and he looked as if he were already in the next world,” he said. Only later that day did the chassidim learn the tragic news that Reb Yosef was no longer among the living.

Another incident occurred after the Rebbe’s famous Havdalah. Long after drinking the wine, the Rebbe would stare into the becher , meditating on what he saw there. Then he would dip his finger in the wine and write holy Sheimos on the table.

One week, as he studied the inside of the cup, he moaned aloud, a heartrending cry. Only later that night did it become known that the Gerrer Rebbe, the Beis Yisrael, had taken ill that Shabbos. He passed away the next morning.

The Skolya Rebbe saw what others couldn’t. He lived on a lofty plane inhabited by few.

The Eineklach’s Memories

Rav Dovid Yitzchok Eizek’s three grandsons spent many hours in his home — Shabbosos and Yomim Tovim as well as daily visits — but their recollections of their zeideh are not the typical, grandfatherly sort. As both Reb Yisroel Mordechai Rabinowitz and his brother Reb Dov Berish say, each in his own words, “He may have been our grandfather, but to us, he was first and foremost the Rebbe.”

They felt a strange mixture of awe and love in his presence. “He would bless us on Friday nights, just as he would all the chassidim who came in with kvittlach. He would place his holy hand on our heads and say the words of Birkas Kohanim, and my heart would pound with a fearful wonder.”

What about regular conversations? There were none. There was nothing mundane in the Rebbe’s life, and though the children knew he loved them, he simply wasn’t capable of small talk.

Reb Yisroel Mordechai shares a memory. The Rebbe would use a Rav Yaakov Emden siddur for certain tefillos, and in time it grew tattered. His grandson –— the present Rebbe — suggested taking it to a bookbinder, and the Rebbe agreed. The binder took one look at the old siddur and told the young men who’d brought that it made more sense to purchase a new one.

The bochurim were scared to tell the Rebbe, lest he think this had been their plan all along, to get his old siddur.

Reb Yisroel Mordechai finally volunteered to speak with the Rebbe. Filled with trepidation, he entered his grandfather’s room and broke the news.

The Rebbe chuckled. “This is what you wanted all along,” he said good-naturedly.

“I knew he was trying to be ‘grandfatherly,’ and I appreciated it,” Reb Yisroel Mordechai recalls. “Then I felt such love mixed with the ever-present fear!”

Another childhood memory: The Rebbe didn’t much care for professional chazzanus or singing, though he himself was a master baal tefillah and composer of niggunim. Nonetheless, his young grandson was chosen to participate in the choir backing a famous chassidic singer; he was even offered many solos on an upcoming recording. The boy practiced for months and months, until the great day arrived. He traveled to the studio, but as soon as he entered, he felt sick, cold, and weak, wanting only to lie down. Within minutes, he was resting on a bench outside the studio, even as his solos were being given to others.

From there, he went straight to the hospital, where the doctor insisted on running a battery of tests. Finally discharged a week later, he went straight to his grandfather, whom he hadn’t seen all week.

The Rebbe embraced him warmly and then looked at him. “People say that the word chazzan stands for ‘chazzanim zennen na’aranim’ [cantors are fools]. I advise you to stop this public singing.”

Of course, that was the end of this child’s performing career.

It should be noted that the Rebbe saw the power of music as a fundamental element of serving Hashem. Once, when teaching a melody he had composed, he commented to his grandson, the present Rebbe, “Your grandfather got ‘fardvei’ket,’ entering an intense state of dveikus, and then this niggun sang itself.”

Another rare conversation to which the Rebbe’s eineklach were privy centered on the aforementioned shin, clearly visible over his left eye. When someone once had the nerve to inquire about it, the Rebbe mentioned that Reb Dovid’l Tolner also had such a shin on his forehead. Then the Rebbe laughed, as if to minimize its significance, and remarked, “In Lita, a picture is a ‘tzurah’ [a problem].” (This is a play on the Lithuanian pronunciation of the word for “picture,” which chassidim pronounce “tzirah.”) He never discussed it again.

There’s an astounding Torah in the Rebbe’s Tzemach Dovid, which he wrote during the bitter year of 1944. At that time, no one knew where his next piece of bread was coming from, but the young Skolya Rebbe was immersed in publishing his work; the world needed the zchus, he said. In this passage, he refers to the words “es mispar yamecha amalei” (Shemos 23:26), where Hashem promises the Yidden long life. The Baal HaTurim notes that amalei is the numerical equivalent of seventy-two, as in the seventy years allotted to man plus the years of his birth and death. The Rebbe adds that yamecha equals eighty, which Tehillim says is the lifespan of a strong person.

His grandson, the present Rebbe, noticed that when the Rebbe said the “Yehi ratzon” before reciting Tehillim, he would change the words, asking to live eighty years instead of seventy. He asked his grandfather about this. The Rebbe smiled. “A tzaddik should have eighty years of life,” he said.

The Rebbe passed away at age eighty, just as he had hinted in Tzemach Dovid almost forty years earlier.

A Heart Filled With Love

The Rebbe was immaculate. His gabbaim related how, after going to the mikveh each day, he would change into a fresh set of clothing, but the clothes he’s worn were “so clean we could have put them back in his drawer.”

Before eating, he would scrutinize the cutlery, holding each piece up to the light to ensure it was spotless. Yet when it came to his fellow Jews, the Rebbe was a different person. The people who frequented his home and table were often smelly and unkempt, but the Rebbe cherished their company.

In his early years, in Williamsburg, his home was filled with war refugees, whom the Rebbetzin fed with maternal devotion. In fact, one room in their small apartment was constantly locked, and a family member wondered about its secret contents. One day the door was left ajar, and this relative was surprised to find it filled with racks of clothing. “I didn’t realize you had a store!” she commented to the Rebbetzin.

The Rebbetzin explained that it wasn’t a store. “It’s just that bochurim often eat here, and they’re dressed in tatters, so after the meal, we invite them in to choose a new clothes.”

Almost daily, the Rebbe’s son Reb Boruch sat with his father and wrote out tzedaka checks. More than once, Reb Boruch worried that there simply wasn’t enough in the Rebbe’s bank account to cover the large sums he was giving. “Don’t worry,” the Rebbe assured him. “By the time the checks clear, more people will come in with kvittlach.”

Though the Rebbe donated more than eighty percent of his income to tzedakah, he filled out a T-40 each year, declaring every last cent that came in from kvittlach. When his son protested that tzedakah was tax-free, the Rebbe replied that America was a medinah shel chessed, so one had to show hakaras hatov.

Other have suggested that the Rebbe had another intention as well: He refused to allow the US government to be a partner in his holy work!

In the Upper Realms

Who was the Skolya Rebbe? A scion of the Rebbes of Yampoli, a line that began with Reb Boruch’l of Mezibuzh, grandson of the Baal Shem Tov himself and the Zlotchever Maggid. His grandfather, Reb Eliezer Chaim of Yampoli, was held in great esteem by the Sanzer Rav and the Sfas Emes. In the early twentieth century, as he started encouraging his chassidim to immigrate to America, he himself decided to visit. It was meant to be a temporary stay, but Providence decreed otherwise: He passed away in New York and was laid to rest in Queens. So when his grandson, the Rebbe, arrived in this country, he had a place to unburden his troubled soul, a place that had been Divinely prepared for him.

The Rebbe’s father, Reb Boruch Pinchas, was himself awe-inspiring. When the famed Reb Shlomo of Sassov had difficulty with a kvittel, he would refer the petitioner to Reb Boruch Pinchas, who led a thriving chassidic community in the Galician town of Skolya.

After the First World War, the Skolya chassidic court was re-established (as were many others) in Vienna. There Reb Boruch Pinchas passed away, and at the tender age of twenty-one, his son Reb Dovid Yitzchok Eizek assumed the title of Skolya Rebbe.

Not long afterward, the Rebbe attended the legendary Kenessiah Gedolah of Agudath Israel and met the gedolim of the day. Pictures of the event show the youthful Rebbe sitting at the dais among the elder tzaddikim of the generation. It is said that when the Imrei Emes, the Gerrer Rebbe, met the Rebbe, he remarked, “It’s been a long while since I’ve seen such a lustrous face!”

The Rebbe gained a reputation for both his gaonus in learning and the miraculous happenings in his court. In later years, he once referred to an incident from that era:

A chassid had phoned, asking for a brachah for his wife, who was experiencing a difficult labor. The Rebbe started to tell a story in order to effect a yeshuah for the woman, as is the way of tzaddikim, but the tale he told was not about the Baal Shem Tov or the Berdichever; it was about himself:

In Vienna, the Rebbe had received a similar request. In response, he had handed the petitioner his snuffbox and instructed him to have his wife smell its contents. The chassid protested that it was impossible, that the doctors would never allow him to get that close to her, but the Rebbe repeated the instructions. As soon as the woman smelled the snuff, she delivered a healthy baby.

Just as the Rebbe concluded this story, the phone rang. It was the grateful chassid, informing the Rebbe that his wife had given birth to a healthy baby!

After the war, the Rebbe had arrived in America, settling first on the East Side, then in Williamsburg, and ultimately in Boro Park. Though, as mentioned, he rarely ventured out of his confines, he had some very illustrious admirers, among them Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky. Rav Yaakov, his neighbor in Williamsburg, had a yahrtzeit one Motzaei Shabbos and happened into the Skolya shtiebel for Maariv. When he came in, the Rebbe was in the middle of Shalosh Seudos, an amazing spectacle.

At the Rebbe’s tisch, someone would customarily read out a random pasuk from the parshah, while someone else mentioned an unrelated pasuk or maamar Chazal. The Rebbe would then weave both together in a magnificent fashion, drawing on both the revealed Torah and the hidden one.

Rav Yaakov stood mesmerized at and the Rebbe’s fluency in the length and breadth of Torah. The next Shabbos, Rav Yaakov came to Shalosh Seudos to hear the Rebbe once again. The Rebbe honored him with selecting one of the pesukim he was to expound.

Many years later, when the Rebbe was niftar, Rav Yaakov was in Florida. When he heard about the Rebbe’s passing, he remarked to his grandson, “If I had the strength, I would travel to the levayah and be maspid him; he truly had ruach hakodesh!”

The great men of New York, including the Tzehlemer Rav, the Mattersdorfer Rav, and the Rebbe of Skulen, would visit him and give him kvittlach. Rav Aharon Kotler spoke in learning with the Rebbe at a chasunah and is known to have quipped, “On you, Skolya Rebbe, I have taanos: You know how to learn, so why don’t you open a yeshivah?”

But perhaps the Skolya Rebbe’s greatest impact was on the mekubalim of Eretz Yisrael, who were so taken with him that they beseeched him to remain with them as their leader. He visited Eretz Yisrael just once, in 1959, spending his first Shabbos in Yerushalayim. His tisch in the Batei Varsha was like nothing the people of the Holy City had ever seen.

The famed gaon and mekubal Reb Yisroel Yitzchok Reisman was given the honor of selecting a pasuk, and the Rebbe proceeded to elaborate on it in thirty-six different ways. Over the course of that Shabbos, the Rebbe shared another thirty-six explanations on the pasuk, arriving at a total of seventy-two explanations!

For the rest of the Rebbe’s trip, which took him to Tel Aviv and Tiveria, a retinue of new followers accompanied him. It was Reb Moshe Yair Weinstock, a leader of the Yerushalmi mekubalim, who formally invited the Rebbe to remain and serve as their teacher.

The Rebbe replied simply that he had to return to America.

The Rebbe wouldn’t visit Eretz Yisrael again. He had his own private avodah to carry out in his small room in Brooklyn. Only after his holy neshamah ascended heavenward did he come back to Eretz Yisrael. At the time, someone suggested that the much-coveted spot next to the tzaddik Reb Shloim’ke Zvhiller, on Har HaZeisim, be given to the Skolya Rebbe.

Permission was requested of Reb Shloim’ke’s grandson, the Zvhiller Rebbe, Reb Mordeche’le. Reb Mordeche’le agreed, remarking that the Skolya Rebbe would be “a gutte shochein [a good neighbor].”

The cryptic words were understood only two weeks later, when Reb Mordeche’le was niftar and laid to rest near his holy grandfather and the Skolya Rebbe.

Who was the Skolya Rebbe? It is doubtful if we will ever know, ever really understand very much about this mysterious soul taken from another era and placed in our generation.

But we try … we tell the stories and remember the miraculous that became ordinary in his proximity.

But beyond recounting stories, the surest way to remain connected is the way he would have wanted: through learning his Torah, plumbing the depths of his chiddushim in all sections of the Torah…

For that was his true life’s work.

The Skolya Rebbe, Reb Dovid Yitzchok Eisek Rabinowitz, was born in the summer of 1898 in the small town of Brid, on the Hungarian/Czech border. His father, Reb Boruch Pinchas, was the son of Reb Eliezer Chaim of Yampoli, whose grandfather; Reb Yitzchok of Yampoli, was a grandson of the great Zlotchover Maggid, Reb Mechele, and a son-in-law of Reb Boruch’l of Mezibuzh, the son of the tzaddeikes Udel, daughter of the Baal Shem Tov.

At the age of fourteen, the Rebbe received semichah from many of great rabbanim, including the famed Rav Meir Arik, and soon after became engaged to the daughter of Reb Chaim Eisen of Svirzh, a granddaughter of Reb Yehudah Tzvi of Stretin. Tragically, just a few months after their chasunah, the town of Svirzh was raided by soldiers, who pillaged Jewish homes. Fearing for her life, the young Rebbetzin jumped out of a window and fell to her death.

The broken widower returned to his father’s home. For the next five years, throughout the First World War, he was at his holy father’s side, surviving bitter imprisonment and privation. After years of wandering, the Skolya Chassidus was once again re-established in Vienna, where Reb Boruch Pinchas emerged as a leading figure for the burgeoning refugee community. A magnificent Skolya beis medrash was erected, and the Chassidus thrived.

During this period, the Rebbe remarried. The tzaddeikes Yocheved Esther Devorah, a daughter of the Burshtiner Rav, Reb Moshe Dovid Landau, became his life’s partner in all his holy undertakings.

In Adar of 1920, Reb Boruch Pinchas was niftar, and his young son, only twenty-one, was crowned as Rebbe. Reb Chaim Yitzchak Yeruchom of Altsdadt entered his room with the very first kvittel. The reputation of the young Skolya Rebbe as a great scholar and miracle worker spread, and he was invited to spend Shabbos in kehillos across Poland, Galicia, Romania, and Hungary, though he based himself in Vienna. The Chassidus flourished until World War II. As the danger grew, the Rebbe sent his wife and children, who were Austrian citizens, ahead to America, while he, accompanied only by his beloved son, Reb Yoseph Boruch Pinchas, hid in the home of his brother-in-law, Reb Sholom Frankel (later of Monsey).

Throughout the war years, the Rebbe was surrounded by open miracles, and eventually he and his son reached Switzerland, where they were reunited with the rest of the family. At the end of the summer of 1939, they arrived in America, and the Rebbe settled on Henry Street, on the Lower East Side.

In 1941, the Rebbe established one of the first chassidishe shtieblach in Williamsburg, and the Skolya beis medrash would remain a magnet for people seeking Torah and chassidus for the next thirty years.

In 1974, New York City exercised its right of eminent domain and took over the Rebbe’s Williamsburg beis medrash, whereupon the Rebbe acquiesced to the requests of his children and chassidim and moved to Boro Park. During the last five years of his life, his beis medrash on 48th Street was filled with all sorts of Yidden: prominent talmidei chachamim, ba’alei avodah who had found a spiritual guide, and simple, brokenhearted souls seeking a yeshuah.

During the last year of his life, the Rebbe dropped several hints that his end was near, and during the winter of 1979, he took ill. His family brought him to London for treatment, and there, on 6 Shvat, leil Shabbos parshas Bo, he returned his holy neshamah to his Creator.

He was laid to rest on Har HaZeisim, next to Reb Shloim’ke Zvhiller who, like him, was a “ben achar ben” of the Zlotchover Maggid.

At the levayah, the Rebbe’s brother crowned a new Rebbe in the name of the family and chassidim, expressing the Rebbe’s will that the oldest son of Reb Yoseph Boruch Pinchas, Reb Avraham Moshe, assume the exalted title of Skolya Rebbe.

To this day, the Chassidus flourishes under the Rebbe’s inspired leadership, much in the manner that the Rebbe, ztz”l, set forth; the Skolya Rebbe rarely leaves his own beis medrash and is known as an accomplished talmid chacham and mekubal. He is a prolific author, having written over twenty-five sefarim on a wide range of topics.

The Skolya Kollel Avreichim is perhaps the only chassidishe Kollel where the Rebbe himself maintains the sedarim and learns along with the yungeleit. The Rebbe upholds his grandfather’s traditions, leading the spirited Friday night davening himself using the unique nusach of the old Rebbe, which dates back several hundred years. Many are drawn to the beis medrash on 48th Street for the tisch, where the Rebbe delivers profound divrei Torah.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 244)

Oops! We could not locate your form.