The Road Less Traveled

| September 26, 2023A virtual tour of the Land of the Thunder Dragon with serial traveler Moshe Klein

Photos: Moshe Klein, AP images, Personal archives

I’d venture to say that few readers of this magazine have ever heard of Bhutan, a landlocked eastern Himalayan kingdom.

Also known as the Land of the Thunder Dragon because of the severe thunderstorms that can sweep the area, Bhutan deals in extremes. It has no traffic lights and no indoor heating, despite the fact that winter temperatures can dip below freezing. It had no television or Internet until 1999, and its main airport is reputed to be one of the world’s most dangerous. It is the only carbon-negative country in the world, and every single one of its citizens marks their birthday on the exact same day.

Given those realities, is it any surprise that serial traveler Moshe Klein found himself drawn to Bhutan?

And while some might be put off by Bhutan’s hefty daily tourist fee and the obligation to sign the kingdom’s pledge of friendship, these only added to the tiny country’s allure. Just weeks after Succos last year, the 29-year-old Satmar chassid from Williamsburg, New York, and his wife Esther boarded their Drukair flight from Nepal to Bhutan.

Inspired by his personal mission to document lesser-known Jewish communities, especially those that are on the verge of disappearing, Klein made his first foray into the world of serious travel seven years ago, with a pre-Abraham Accords trip to Qatar, United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia. By the beginning of last fall, he had already been to 89 countries, with visits to better-known locales offset by trips to Iraq, Ethiopia, and Djibouti. Typically, the Kleins had been averaging trips three times annually, but with an extensive bucket list of countries to cover, last year they decided to take some time off from their jobs, spending seven months on a 24-country trip.

As in previous jaunts, the itinerary blended locations that offer conveniences for the Jewish traveler, like Hong Kong and European countries, with others that are considerably more challenging, like Myanmar, Eritrea, and Turkmenistan. Klein, who often lectures about his travels, is the first to admit that staying in a place with zero Jewish infrastructure isn’t easy, especially on Shabbos, and that sometimes you just want to see another heimish face.

“If we’re coming from New York, we bring along tuna, crackers, and energy bars, and if not, we live on what we get — fruits, vegetables, and preparing whatever we can in a small pan,” he says. “Sometimes we catch fish, but I did lose 15 pounds in some of the more hard-core places we visited.”

Bhutan was the fourth stop on Klein’s post-Succos itinerary, which had him heading from the United Arab Emirates to Nepal, one of the few places with direct flights to Bhutan.

Obtaining permission to enter the kingdom is a multistep process in which prospective visitors need to affirm their commitment to respecting Bhutan’s holy sites, preserving the country’s peace, and leaving its wild spaces, flora, and fauna in pristine condition. Bhutan’s daily Sustainable Development Fee — priced at $200 at the time of Klein’s visit, but recently halved to $100 — is mandatory for every visiting adult, and has tourists subsidizing the free health care, education, and vocational training that is offered to all citizens. The collected monies also help support the kingdom’s infrastructure, environmental preservation, and conservation initiatives, as well as its tourism and hospitality industry.

Only a few pilots are qualified to fly through the cliffs and valleys into Bhutan’s Paro International Airport, where tourists fork over a hefty fee for a mandatory tour guide

Fasten Your Seatbelts

While the Kleins were able to obtain tickets from Nepal to Bhutan’s Paro International Airport, the 50-minute direct flight isn’t without its share of drama. Nestled as it is between 18,000-foot-high mountain peaks, Paro is known to be among the most dangerous airports in the world, with multiple video clips online demonstrating just how frightening takeoffs and landings can be. Pilots have to traverse a long winding valley, oftentimes flying at a 45-degree angle without any radar assistance, with Paro’s relatively short 7,431-foot runway only visible just prior to landing. Given those realities, just a handful of the 35 pilots in Bhutan are certified to land at Paro, and planes fly in and out only during daylight hours. Not surprisingly, bad weather conditions often translate to delayed and canceled flights for those flying in and out of the kingdom.

Paro is served by just two carriers — the state-owned Drukair, also known as Royal Bhutan Airlines, and the privately owned Bhutan Airlines — with a total of seven planes in their combined fleets. And forget about trying to find discounted airfare; tickets for flights out of Bangladesh, India, Singapore, and Thailand cost several hundred dollars.

Once he was already paying a premium price for his flight, Klein booked a business-class ticket to Bhutan, choosing a seat that would give him the best views of Mount Everest. He found himself sitting next to Japan’s State Minister for Foreign Affairs Takei Shunsuke, with both men spending their time in the air enjoying the breathtaking views. A high-ranking Bhutanese religious leader who was situated nearby took advantage of the flight to catch a quick nap.

“Usually, people like that would have private jets, but this was the only way in and out of the country at the time, since all of the land borders were still closed because of Covid,” Klein notes.

The Japanese minister was the first to set foot on Bhutanese soil, with the remaining passengers disembarking only after he was accorded an official kingdom welcome. The religious leader on Klein’s flight also received the VIP treatment and was greeted on the tarmac by followers who were overjoyed to receive his blessings and kiss his hand before he was whisked away in an official kingdom car.

Even as a seasoned traveler, Klein recalls his first moments in Bhutan as somewhat surreal.

“It felt like a different planet,” he says. “The views, the air, the color, the art, even the way the buildings looked. There was a calmness and an emptiness in the airport, it just didn’t feel real.”

While at this point visitors are permitted to venture out on their own in Paro and Bhutan’s capital city of Thimphu, that wasn’t the case during Klein’s visit, with tourists’ itineraries tightly controlled by the kingdom. He was met at the airport by a driver and a guide who would accompany him throughout the trip. Guides are still required in the vast majority of the kingdom, and for good reason. Bhutan’s official travel site cautions visitors never to go out alone in the wild because of predatory animals, such as Bengal tigers, snow leopards, Himalayan black bears, and the nearly extinct dhole, all of which can be found even relatively close to the kingdom’s cities.

Much like airfare to Bhutan, the cost of a tour guide isn’t exactly budget friendly. And while the $350 fee per day, per person, included a driver and tour guide and all accommodations, it was still one of the most expensive of the many trips Klein has taken. Clearly Bhutan isn’t looking to become the next Dubai or Panama, with the kingdom taking a less-is-more approach to tourism.

“Part of the reason they ask for a large amount of money from tourists is so that they can have high-impact, low-volume tourism,” explains Klein. “I saw fewer than ten tourists on our flight to Bhutan, and during the time we were there, we saw almost no tourists at the tourist sites.”

A World Apart

The Kleins spent their first night in the kingdom in a new hotel in Paro where, in true Bhutanese style, wooden décor and color motifs abounded, and the hospitality was excellent. Since he and his wife were the only guests on premises, Klein was able to get hot kosher meals by turning on the kitchen fires himself, and the hotel chefs were happy to prepare vegetables to his standards in a pan he had brought from home.

With temperatures typically dipping to just above 30 degrees Fahrenheit in November and no indoor heating, the Kleins were given extra blankets and an electric heater to help ward off the chill.

“It can get very cold because it’s so high up in the mountains,” he says. “During the day, the sun protects you and it can actually get hot, but when night falls, it becomes really cold, cold enough that I bought a coat while I was there.”

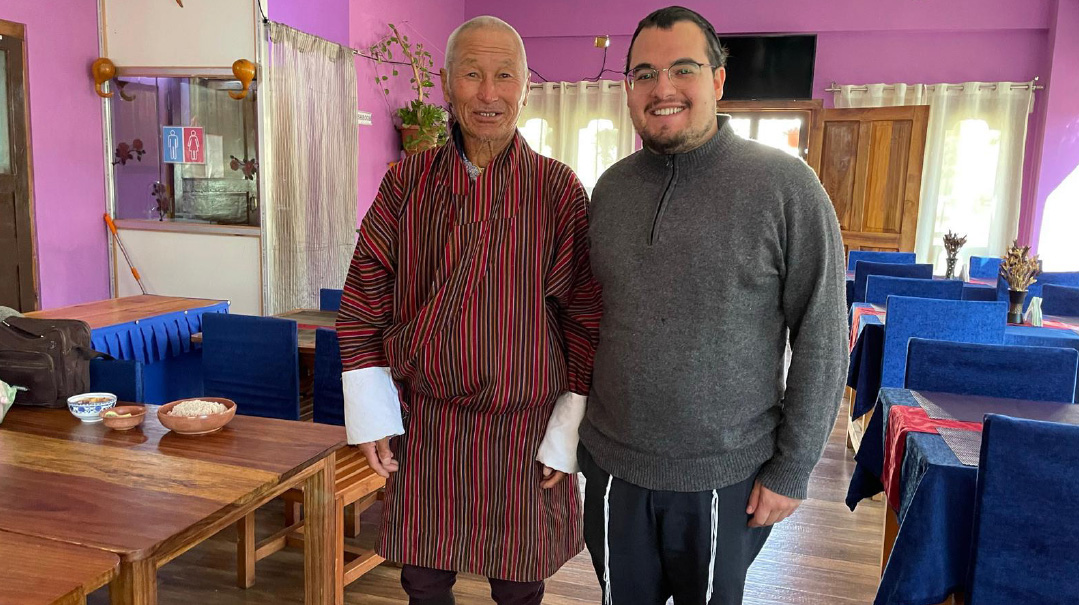

Bhutan’s national dress code is mandatory for citizens whenever they enter schools or government offices, and during festivals and other important occasions. Women wear long-sleeved blouses and an ankle-length kira, a folded strip of cloth that can be worn as a dress or a skirt. Klein found the striped or plaid belted gho worn by Bhutani men reminiscent of a beketshe, albeit a rather colorful one.

“The socks are pretty much what you might see on chassidish rebbes or how, lehavdil, priests dressed in the 1800s, black and all the way up to the knees with shoes like the ones chassidim wear,” reports Klein.

Color plays a significant role in Bhutani dress. Only the kingdom’s ministers wear orange kabneys, including prime minister Dr. Lotay Tsherin, a physician who spent three years in Israel before moving back to his homeland and throwing the towel into the political ring

Color plays a significant role in Bhutani dress, particularly when it comes to the kabney, a long, folded ceremonial silk sash that is draped diagonally over the gho from the left shoulder to the right hip. While the kabney of a simple person is white and fringed, the kingdom’s ministers wear orange kabneys, but most significant of all is the saffron-colored kabney, worn by only two people in the kingdom — Bhutan’s monarch, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, and its head abbot, Tulku Jigme Chhoeda. Klein tried on a gho, but he chose to wear his own attire on his visit, finding it more comfortable than the kingdom’s cultural dress.

On his travels in Bhutan, Klein met only a few people who even knew what a Jew was, with the exception of a large group of monks he spoke with when they made a quick stop in the hotel his first night there.

“Surprisingly, they knew a lot about Yiddishkeit, and they said whenever they want higher spirituality, they take it from the Torah,” says Klein. “One of the monks told me that when he meets Israelis who go on spiritual journeys after leaving the army, he tells them, ‘Go back to your own country and study there because you won’t get it here.’ ”

In another instance, someone who understood from Klein’s appearance that he was Jewish gave him a thumbs up and said, “Bibi Netanyahu is good.”

“He was sure I was Israeli, but I told him that I’ve got Joe Biden,” recalls Klein. “He just kept saying, ‘Shalom, shalom,’ which is something I get a lot because people can’t always distinguish between Israel and Jews.”

A Slice of Life

It didn’t take long for Klein’s tour guide to realize that it wasn’t just the yarmulke, beard, and peyos that set his passenger apart from the visitors he typically took around the kingdom. The local Buddhist religious sights favored by tourists weren’t on Klein’s six-day itinerary, which he crafted to provide a real flavor of kingdom life.

Venturing off the beaten path to Bhutan’s countryside, Klein spent a night in the small village of Punakha at a “home stay,” a private dwelling that is governmentally approved to lodge guests. The cottage was located approximately two and a half hours outside Thimphu on a property gifted to a former secret service agent by the king. It had no furniture at all, not even beds — instead, there were mattresses, pillows, and carpets on the floor. Pictures of the royals adorned the walls, something Klein saw frequently in Bhutan, where the king and his family play a significant part in everyday life and culture.

“Whenever you ask people how they are doing they all say the same thing — ‘Due to the graciousness of the king, we are doing very well,’ ” Klein remarks.

People with red or even missing teeth were a common sight on the local farms. The phenomenon is linked to an Asian treat: areca nuts wrapped in the betel palm’s lime-coated leaves. The nuts, which are addictive and known to have stimulant properties, are anything but tooth-friendly, though, leaving red stains and even causing tooth loss. According to CNN, studies have shown that they cause oral cancer as well.

“We saw a lot of people chewing those nuts, and at a random stop at one house, we saw a family working on their peanut field, pulling them out of the ground like you do with carrots,” notes Klein. “It looked like real avodas parech, the way they were working outside in the sun.”

Of course, Klein had no intention of leaving Punakha without crossing its famed 525-foot-long suspension bridge, reputed to be one of the oldest in the world. Adorned with colorful prayer flags, the bridge spans the Puna Tsang Chu River, and despite its tendency to swing in the wind, it’s reported to be surprisingly stable, thanks to cables that anchor it to enormous blocks of concrete on both shores. While under normal circumstances Klein might have been nervous about crossing an ancient bridge that soars high over a fast-moving river, none of those thoughts entered his mind in Punakha.

“It’s such a significant place to visit that I didn’t even think about the danger until I was off it,” he recalls.

Klein, who works as a teacher when he’s not on the road and considers himself a researcher of Jewish heritage, tries to work an education-oriented aspect into his travels. He had multiple opportunities in Bhutan to interact with schoolchildren, who typically walk long distances to get to school each way and love speaking to foreigners. A visit to a nonpublic school in Thimphu was a memorable experience, with students peppering Klein with questions about life in New York and sharing their own aspirations of attending Ivy League colleges and maybe one day becoming doctors and engineers.

“They were incredibly respectful,” says Klein. “They stood up for us when we entered and didn’t sit down until I told them they could. The whole time I spoke to them, I didn’t see anyone playing with a pencil or talking to a friend.”

Another fascinating aspect of life in Bhutan is the lack of traffic lights, even at the biggest intersections. Traffic is shepherded along the roads in the kingdom’s cities by police officers wearing white gloves, who resort to unusual vehicle control methods when the occasion warrants.

“Sometimes instead of telling cars to stop and go, they manage traffic with a dance,” says Klein. “People slow down to watch their performance.”

Punakha’s hospitality meant no furniture, but lots of mattresses, pillows and carpets. At the hotel in Paro, he was able to turn on the kitchen fire himself and have the chefs prepare vegetables in the pan he’d brought from home

Crowning Glory

The land of Bhutan was inhabited for hundreds of years before it was unified into a country in the early 1600s. Bhutan became an absolute monarchy in 1907, a change that heralded an era of development and modernization, with the crown passing from father to son in the House of Wangchuck.

Understanding the importance of transitioning the kingdom to democracy, Bhutan’s fourth ruler, King Jigme Singye Wangchuck, voluntarily abdicated the throne in 2006 in favor of his 19-year-old son, paving the way for the upcoming political shift. The kingdom held its first general election for its newly formed National Assembly in 2008. It is now a constitutional monarchy, with the king serving as head of state, Bhutan’s cabinet wielding executive power, and Parliament taking on the legislative component of government.

While King Jigme Khesar, Bhutan’s fifth and current king, may have seemed young when he ascended to the throne before he turned 20, his father was actually three years younger when he became the kingdom’s ruler. According to the Washington Post, the king played varsity basketball as a student at the Cushing Academy and Wheaton College, both in Massachusetts, earned a political science degree from the University of Oxford in England, and is an accomplished artist and photographer.

Polygamy is permitted in Bhutan, but the king has only one wife, who is ten years his junior. Their three-day wedding celebration is reported to have been Bhutan’s largest media event ever. The royal couple has three children: two boys, ages seven and three, and a newborn daughter.

Shalom, Bhutan!

Bhutan does not have diplomatic relations with any permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, including the United States, although the two share “warm, informal relations” according to the US State Department. Prior to opening itself up to tourism in 1974, the only countries Bhutan had official relations with were India and Bangladesh, but by November 2020, that list had grown to include another 51 countries. One month later, Israel and Bhutan officially established formal diplomatic relations, a move that was hailed in a joint press release as creating “new avenues for cooperation between the two countries in water management, technology, human resource development, agricultural sciences, and other areas of mutual benefit.”

A political buff, Klein was thrilled to score an interview with Bhutan’s prime minster, Lotay Tshering, a former urologist who threw his hat into the political ring in 2013 and was elected to his current position five years later. Tshering, who lived in Bat Yam for three years, is fluent in Hebrew, and they communicated in Hebrew as they discussed foreign policy and other topics.

Establishing formal ties with Israel was a smart move for Bhutan, according to Tshering, who expressed his admiration for Israel for its expertise in water, technology, and, most importantly, utilizing its citizens’ talents to further growth and development. Tshering noted that Bhutan is selective when it comes to establishing diplomatic relationships with other nations, describing Israel as one of Bhutan’s “chosen countries.”

Asked if Bhutan was considering opening an embassy in Israel, Tshering demurred, saying that there was no economic justification for that move at this time. As to where a potential embassy might be located, Tshering would not specify if Jerusalem was a potential candidate, remarking only that Bhutan would not bow to political pressure and would choose a location that suited both its needs and Israel’s.

“When we decide, we will decide it together,” said Tshering, adding, “and I love the State of Israel.”

Some might consider Tshering’s professional shift from medicine to politics to be a major move, but the prime minister took a different view of the matter, noting that he continues to do telephone consultations, and even surgeries. While his heart remains in the hospital, Tshering realized that politics offers opportunities to create systemic change in Bhutan.

“As a surgeon, I could operate on only one patient at a time, but now I can operate on an entire country at once,” Tshering told Klein. “Even as a politician, I am still a surgeon, only instead of a knife, today I mainly operate with my pen.”

Klein’s conversation with Tshering also touched on Bhutan’s efforts to create a society of responsible, literate citizens who can welcome visitors and provide them with an authentic, professional experience. Acknowledging that visiting Bhutan can be pricey, Tshering noted that he has seen that tourists hold the kingdom and its citizens in high esteem.

“I am glad that you came to Bhutan feeling that it’s costly, because it shows that it was important for you to visit here and that you made an effort to come,” said Tshering. “Our job is to make sure that you leave here with a unique experience that might have been a little more expensive, but was definitely worth the visit.”

Klein was thrilled to score an interview with Prime Minister Tshering, who says he “loves the State of Israel”

Did you know…

- With an area of approximately 14,824 square miles, Bhutan is about 75 percent larger in area than Israel. Despite its smaller size, Israel’s population of 9,364,000 dwarfs Bhutan’s total of approximately 770,000 citizens.

- Prosperity is measured in Bhutan not on a monetary scale, but rather by a measure known as Gross National Happiness. Instituted in 1972, the policy prioritizes citizens’ wellbeing by offering free health care and education, promoting cultural and economic resilience, and launching conservation efforts. The Gross National Happiness index also allows tourists into the kingdom (starting in 1974) as a means of generating revenue; previously it was closed to outsiders to limit foreign influences.

- At just over 24,800 feet, Gangkhar Puensum is Bhutan’s highest peak and the tallest unclimbed mountain in the world. All mountains in Bhutan that are higher than 19,685 feet are off limits to mountaineers by law.

- With more than 70 percent of the kingdom covered in trees, Bhutan absorbs more carbon dioxide than it produces. It is the only country on the globe to achieve the distinction of being “carbon negative.”

- Bhutan is the only country in the world that bans the sale of tobacco. Although it can be imported from other countries, albeit with significant taxes added on, smokers who light up outside designated smoking areas face jail time.

- Dry Tuesdays, a law that prohibited hotels, restaurants, and other licensed businesses from selling alcohol on Tuesdays, was repealed on June 30th of this year.

- Everyone in Bhutan turns one year older on New Year’s Day, although national holidays throughout the year celebrate the birth anniversaries of members of the kingdom’s royal family.

- Archery was declared to be the kingdom’s national sport in 1971, the same year Bhutan became a member of the United Nations.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 980)

Oops! We could not locate your form.