The Return of Trump: Security Detail

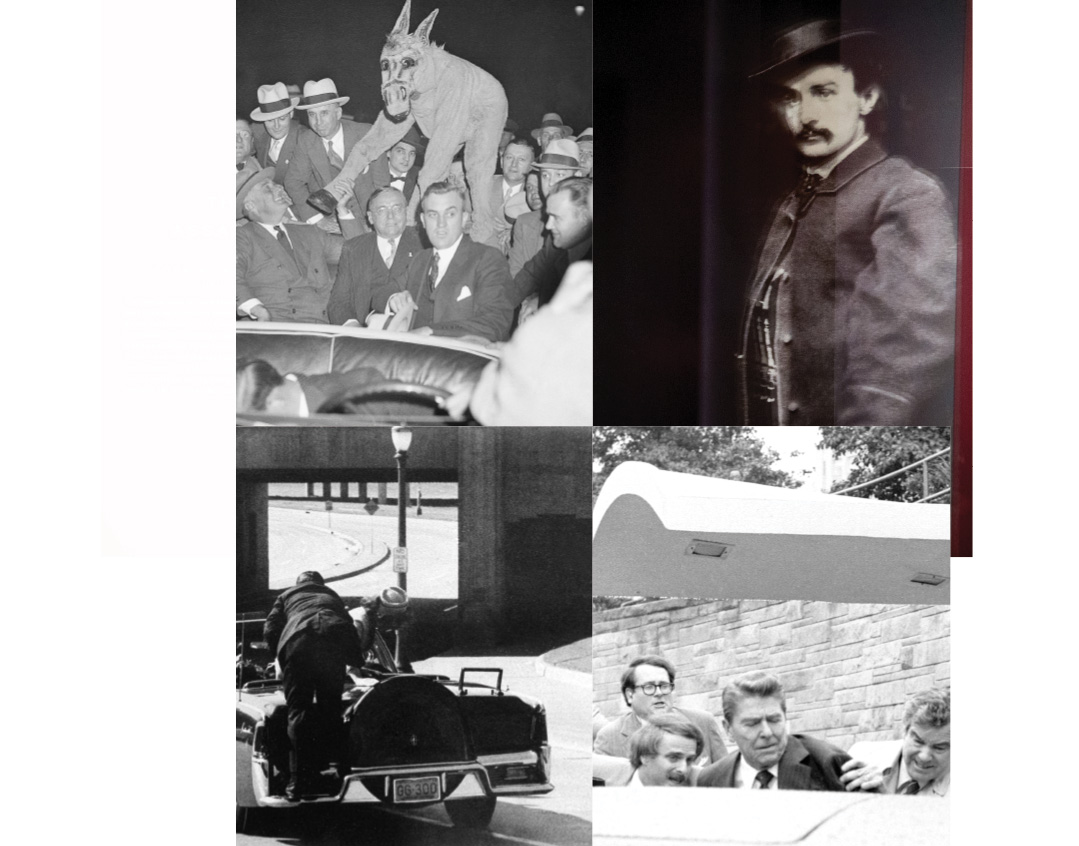

The Secret Service has a storied past of triumph and tragedy

Photos: AP Images

Separated from death by millimeters in an act of what he recognized as Divine Providence, the former president looks unstoppable — especially against Democratic paralysis. Shaken, defiant, and now professing unity, Donald Trump takes center stage again.

When a lone-wolf assassin pulled the trigger at Donald Trump’s televised rally in Pennsylvania this week, the shots were literally heard around the world. The failed hit might well have upended the 2024 race.

The attempted assassination of former president Donald Trump has cast a spotlight on the United States Secret Service, the federal agency tasked with the security of the sitting president as well as former presidents and candidates for the office.

Experts have expressed incredulity that someone like would-be assassin Thomas Matthew Crooks could get so close to the former president. Onlookers told the media they were shouting to law enforcement that Crooks was scaling a building to get into position to fire at Trump, but the response was too slow.

The current head of the Secret Service is Kimberly Cheatle, a woman who joined the agency as an agent in 1995 and now finds herself under intense public scrutiny. She was a member of the detail assigned to protect Vice President Joe Biden during the Obama administration. Biden appointed her to head the agency in 2022. One of Cheatle’s goals upon taking the helm was to prioritize diversity, equity, and inclusion in hiring, and to increase the number of female agents by 30 percent.

Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, under whose department the Secret Service operates, is facing charges from Republican lawmakers that he denied stronger protection for former president Trump on several occasions. Rep. Mike Waltz (R-FL), a member of the House Intelligence Committee, said this week that “very reliable sources” told him that repeated requests for beefed-up protection from the Trump campaign were rejected by Mayorkas. A spokesperson for the Secret Service denied the charge.

The Secret Service invariably draws scrutiny for its failures, and many of its successes must remain classified. While the agency in its current form will face a Congressional investigation, its storied past shows that its personnel have earned their pay on numerous occasions. Unfortunately, this agency’s evolution has also frequently been driven by glaring errors, many of which ended in tragedy.

How has the relationship between American politicians and their protectors evolved throughout the nation’s history?

Palace Guard

The origins of the Secret Service date back to 1865. President Abraham Lincoln at the time discussed the need to create a special protective force, though its original aim was to combat currency counterfeiters.

Lincoln was assassinated on April 14 of that year and did not live to see his vision realized. However, just a few weeks later, on July 5, the Secret Service was created as a division of the Department of the Treasury, with William Wood, a Treasury investigator, sworn in as the first head over a team of ten.

Back then, the idea of a special force dedicated to the president’s security was widely dismissed. Americans were unenthusiastic about creating a “palace guard” for their chief executive, like the monarchs of Europe had. Even after President James Garfield was assassinated in 1881, the need for special protection for presidents went unaddressed.

Everything changed in 1894. That year, Secret Service director William Hazen learned of plans to assassinate President Grover Cleveland. Hazen unilaterally decided to provide special security for the president, an unprecedented action. But because Hazen acted without Congressional approval, his decision, though prudent, would eventually cost him his job.

In 1897, when President William McKinley took office and learned of Hazen’s actions, he dismissed him. Ironically, in 1901, McKinley himself would become the third American president to be assassinated within 36 years. This tragedy finally spurred Congress to consider the necessity of a presidential security force. In 1906, Congress approved a measure that provided the president of the United States with round-the-clock protection from two Secret Service agents.

Theodore Roosevelt was the first president to officially receive Secret Service protection. Yet when he left office in 1909, he did not have that benefit, and he would suffer for it.

On October 14, 1912, a former saloonkeeper named John Schrank attempted to assassinate Roosevelt, who was then campaigning in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to return to the White House. Schrank’s bullet embedded itself in Roosevelt’s chest, but not before it passed through the steel case of his eyeglasses and a folded 50-page copy of his speech tucked in his jacket pocket. Schrank was quickly subdued; the crowd might have lynched him if not for Roosevelt. Calmly, Roosevelt assured onlookers he was all right and instructed the police to take Schrank into custody.

Roosevelt, an avid hunter, had enough anatomical knowledge to know that he did not need immediate medical treatment, and he proceeded to deliver his speech with remarkable composure: “I don’t know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot — but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose.”

The Secret Service chalked up a win in 1950. While the White House was undergoing renovations, President Harry S. Truman was staying at Blair House. On November 1, two separatist Puerto Ricans, Oscar Collazo and Griselio Torresola, sought to make a statement by assassinating the president. Secret Service agents Floyd Boring and Leslie Coffelt noticed the two lurking around. When the would-be assassins attempted to shoot, they were met with a barrage of gunfire from the agents. The shootout ended with the assailants dead, and Coffelt became the first and only agent to die defending a president of the United States.

A Fateful Day in Dallas

John Fitzgerald Kennedy came to power in 1961, and by 1962, full-time protection for the vice president had been approved. Under the Kennedy administration, presidential security was significantly ramped up, but experts say JFK was a “difficult person to protect” because he enjoyed mingling with the public.

Kennedy would often joke with the agents, saying, “You don’t want anything to happen to me, or you’ll have to work for [Vice President Lyndon] Johnson!”

These words would become a tragic premonition on November 22, 1963. Kennedy was in Dallas to mend relations with local Democratic figures, and the Secret Service had received threats about a possible assassination attempt. However, it was nearly impossible to check every building, and the threats were not taken very seriously. In addition, several agents were reportedly sleep-deprived and some were too inexperienced to handle such an operation.

According to the findings of the Warren Commission, Kennedy was shot while riding with his wife in a presidential motorcade by Lee Harvey Oswald.

Agent Win Lawson, responsible for planning the Dallas security detail and considered an exemplary serviceman, lamented publicly, “I’m the first agent in Secret Service history to lose a president.”

It is well known that Jackie Kennedy later complained to her personal assistant, believing that several agents were unprepared for such a threat.

After JFK’s assassination, President Johnson ordered an investigation into security protocols. The number of agents around the president was immediately doubled, from 28 to 50 agents for each trip. Agency head James Rowley secured approval to hire 200 additional agents to bolster the Secret Service and negotiated with IBM to create a system for evaluating potential threats.

Another tragedy in the Kennedy family would force the Secret Service to expand its duties further.

Protecting Candidates

In mid-1968, the Democrats were selecting their presidential nominee. Robert F. Kennedy, former attorney general under his brother and then senator from New York, was leading. A champion of progressive ideas and human rights, and very popular among African Americans, RFK seemed to be on a smooth path to the White House.

After winning the California and South Dakota primaries, on June 5, Bobby Kennedy addressed his supporters in a ballroom at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. After concluding his speech, Kennedy decided to exit through the kitchen, against his bodyguard’s advice. In a narrow hallway, Robert Kennedy was shot and killed by Sirhan Sirhan, a Palestinian who opposed RFK’s support for the State of Israel.

The assassination of RFK caused a revolution in US security protocols, and President Johnson immediately ordered the Secret Service to also protect prominent presidential candidates.

One beneficiary was Alabama governor George Wallace — although fate would intervene. Wallace made numerous attempts to become the Democratic presidential candidate, and in 1972, the Southern conservative seemed poised to succeed. It was a tight race against George McGovern and Hubert Humphrey, but Wallace’s camp believed he could win.

Wallace’s extreme pro-segregationist statements had generated significant opposition in more liberal areas like Maryland, where he was headed for a rally. Jimmy Taylor, leader of Wallace’s Secret Service detail, was uneasy. When a man began shouting for Wallace to shake his hand, Taylor spoke up.

“Don’t do it, Governor,” Taylor urged.

“No problem,” Wallace replied.

Suddenly, an object came between Wallace and Taylor. Arthur Bremer, a man with psychiatric issues, seized the moment, shooting Wallace four times, wounding him in the spine and leaving him paralyzed from the waist down. Shortly thereafter, Wallace withdrew from the race for the Democratic presidential nomination.

Fifty Feet Away

After the tumult of the Watergate scandal under the Nixon administration, dynamics with the Secret Service shifted with successor Gerald Ford. Agency director Stu Knight introduced innovations such as advanced technology and psychological support for agents. But despite these improvements, significant missteps occurred.

In 1975, there were two assassination attempts on President Ford within just three weeks. On September 5, the president was at a Sacramento hotel. It was a beautiful morning, and Ford decided to take a walk, flanked by his security detail. Outside, a crowd eagerly awaited the president. Unbeknownst to Ford, among the crowd was Lynette Fromme, a follower of the Manson Family. The hero of the day was agent Larry Buendorf, who risked his life to intercept Fromme and stop her assassination attempt.

Just 17 days later, in northern California, Sara Jane Moore approached another event where President Ford would be present. Moore aimed at the president’s limousine just as he was about to exit and missed his head by mere inches. A Vietnam veteran present at the scene immobilized her.

These incidents prompted changes in security protocols: the public was henceforth required to be at least 50 feet away from the president in public settings.

Just Say No

wo months after taking office, on March 30, 1981, President Ronald Reagan was preparing to address a labor union. Before the speech, he would rest at the Washington Hilton. The location was familiar to agents — presidents had stayed there monthly for years.

For this routine visit, Reagan had a security team of 67 people. While the new rule required a 50-foot distance between the president and the public, it was believed this applied only to official trips. In Washington, strict adherence wasn’t deemed necessary. This was a mistake.

After his speech, Reagan exited the hotel, escorted by four agents forming a diamond around him. He was just steps from the limousine when he heard someone shout, “Mr. President! President Reagan!” He stopped, and in that moment, John Hinckley Jr. saw his chance.

In a severe security lapse, Hinckley fired six shots, one of which hit Reagan, while others seriously injured several agents. Reagan underwent surgery and recovered, though the bullet had come within 25 millimeters of his heart.

This incident forced another reevaluation of presidential security. Hinckley had come too close — far too close. The attack on Reagan led to one of the most radical changes: The Secret Service gained the authority to override the president’s wishes regarding security protocols. The man responsible for enforcing this was agent Robert DeProspero, who earned the nickname “Dr. No” within the Secret Service corridors.

A Matter of State

Since the attempt on President Reagan’s life, other presidents have faced threats. For instance, in October 1994, Francisco Martin Duran fired at least 29 shots at the White House, believing President Bill Clinton was inside. In 2005, during a trip to Georgia, a man threw a grenade at President George W. Bush while he was giving a speech; miraculously, it did not explode. In November 2011, Oscar Ramiro Ortega-Hernández fired a semi-automatic rifle at the White House, intending to kill President Barack Obama.

Meanwhile, the Secret Service has grown exponentially. Today, it must provide security not only for the president and his family but also for the vice president and her family, former presidents, their spouses and children under 16, major presidential candidates and their spouses, and visiting foreign dignitaries.

The agency now employs at least 8,300 people with a budget exceeding $3.2 billion. Yet despite this growth, mistakes and lapses can still occur. History has shown that presidential security must be a matter of state and a guarantee for democracy.

However, at the end of the day, security ultimately depends on the One and Only.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1020)

Oops! We could not locate your form.