The Rest Is History

Poland's Jewish glory remains buried firmly in the past

Photos: Eli Itkin; CER

Eight decades after the Nazis obliterated the Warsaw Ghetto to crush the despairing Jewish uprising, Poland is torn over its own part in the Holocaust. Even as many local Jews rediscover their own history, the country remains primarily the graveyard of a lost world

Step behind the high brick walls of Warsaw’s Okopowa Street cemetery, and you’ll find a vanished world. In a space the size of 80 football fields, a quarter-million graves lie side by side. A fable-like quality hangs over the vast necropolis: it’s not so much a cemetery as a jumble of graves overrun by lichen and climbing ivy, swallowed up by the giant forest that has sprung up since World War II.

Entering this still, green kingdom is like walking into a history book. Forgotten geonim and gvirim are buried alongside household names like Warsaw’s first rav, the Chemdas Shlomo, the Netziv of Volozhin, and Rav Chaim Soloveitchik. Here there’s a cluster of markers for the Kotzk dynasty, there is Amshinov, and further along the white ohel of a chassidic dynasty whose memory has faded.

Polish-language inscriptions mark the graves of prewar secular Jews. There’s I.L. Peretz, the Yiddish playwright; Ludwig Zamenhof, creator of Esperanto; a sister of Andre Citroen, founder of the French automotive company.

Resting under the verdant canopy are Agudists, Bundists, Zionists — bitter opponents in their lifetimes, now sharing the same patch of earth.

Eight decades after the Warsaw Ghetto uprising was savagely put down — filling this hallowed ground with the remains of Jewish victims and underground fighters — Okopowa is a reminder that in this country, the Nazis butchered an entire Jewish civilization. Poland is the vast graveyard of that lost world.

While the government is supportive of the Jewish community, and has moved on from efforts to ban shechitah, the country remains conflicted about its recent Jewish history. A controversy over what Israel sees as Poland’s revisionism about its Holocaust record seems to be subsiding, with a new agreement clearing the way for the resumption of high school trips to the country’s death camps.

“We’ll do everything so that Jews can live in Poland according to their faith and in security for another thousand years,” Tomasz Grodzki, marshal of Poland’s Senate told a visiting delegation of the Conference of European Rabbis (CER) last week, referencing both the country’s history and recent tensions.

But unlike many former Soviet countries that have experienced significant revivals in Jewish life, Poland’s glories are firmly in the past, in Okopowa cemetery.

Warsaw once teemed with Jews, but today’s small community hardly makes an impression in the city that was rebuilt by the Communists on the wartime rubble.

MAMMA LOSHEN (top) The giant mural outside the Nozyk shul is a reminder that Yiddish was once everywhere in Warsaw’s streets

Sole Survivor

It’s 7:15 a.m., and in the shade of office and residential buildings in the center of Warsaw, a handful of men are gathered, clutching tallis bags. They converse quietly, or take out a siddur to get a head start. One man, with a flowing beard and a bike helmet, strides up and down in front of a giant mural of an elephant and giraffe riding a preposterously small train captioned in Yiddish “Der Locomotive.”

The crew of middle aged to elderly men are the Shacharis regulars at the Nozyk shul, a beautiful building that is the sole survivor of the hundreds of shuls, shtiblach, and kloizen that once dotted Warsaw.

Chief Rabbi Michael Schudrich says good morning to the security guard at the building’s entrance, and welcomes the mispallelim. Raised in New York, his Polish is fluent, the product of more than three decades in the country.

Once Shacharis is over, we sit down in a side room, and he shares the history of the place, with occasional pauses to interact with requests from the shulgoers.

“We’re now in the southernmost tip of the Small Ghetto, which was south of the main wartime Ghetto,” he explains. “The shul — built in 1898 by a wealthy businessman called Zalman Nozyk — survived the Ghetto’s destruction because by the time of the Uprising, the deportations had already emptied this area, and so it was used by the Nazis as a stable, and there was no reason to destroy it.”

The jumble of Stalinist and Modernist architecture outside the Nozyk shul’s doors is evidence of the utter destruction that somehow spared this building. Ninety-nine percent of the Ghetto was destroyed as SS commander Jurgen Stroop methodically razed it in 1943.

Over the next year, most of the rest of the city followed as the Nazis viciously quelled the uprising of the Polish Home Army, loyal to the London government-in-exile, while the Soviets waited outside the city, ready to move in once the Germans had done their work.

Postwar, a mere remnant of Poland’s glorious Jewish community emerged from the smoking ruins.

“There had been over three million Polish Jews before the Holocaust,” says Rabbi Schudrich. “But after the German defeat, only about 60,000 remained. When the Communists took over, it triggered a further wave of Jewish emigration, and those Jews who remained basically shed their Jewish identity.”

As broken Jews began to pick up the pieces of their lives in the shattered city after the war, Nozyk became a focal point for the community — as it remains today.

On the front wall of the shul is a new sign — just two weeks old — marking the visit of Israeli president Isaac Herzog, who came to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising.

He, in turn, was following in the footsteps of his grandfather Chief Rabbi Yitzchak Eizik Herzog, who visited the shul in 1946 on his famous, heartrending tour of Poland in which he attempted to rescue the Jewish children left by their parents in monasteries.

Grief-stricken at the destruction he witnessed and the thought of those children whom the Church wouldn’t surrender, Rav Herzog composed a kinnah whose English translation is etched on the shul walls:

Though the sea dry out, my eye shall shed a tear;

My affliction is beyond limit and without compare.

Your wrath surges forth in terror and fear;

O Sacred One, before Thee I kneel!

NEW BEGINNINGS Saved from destruction by housing the Nazis’s horses, the Nozyk shul is the only remnant of prewar Warsaw’s Jewish glory

Skinhead’s Story

It was only after Communism ended in 1989 that Jews started to come out of the woodwork, many learning of their Jewish identity for the first time from parents and grandparents. Today’s Jewish community is thought to number something like 30,000 members, but the true figure is likely to be far higher.

“We can’t say with any certainty how many Jews there are in Poland today,” says the chief rabbi. “There are many whose parents concealed their identity from them, and they’re slowly finding their way back to us.”

One such story of return is that of Warsaw-born Pinchas Bramson, the mashgiach at the CER conference, whose beard and yarmulke make him a rare sight among locals. Pinchas — formerly Pawel — was not only once unaware of his Jewish roots; he actively detested Jews.

“I was a skinhead, and used to go to football games and shout anti-Semitic slogans, and beat up local kids and homeless people,” he says.

What Rabbi Schudrich calls Pinchas’s “skinhead to covered-head” metamorphosis was the subject of a 2010 CNN documentary that made waves internationally, in which Pinchas spoke of his background in the neo-Nazi scene where he met his wife.

“I was a nationalist 100 percent,” said Pawel. “Back then, when we were skinheads, it was all about white power, and I believed Poland was only for Poles. That Jews were the biggest plague and the worst evil of this world. At least in Poland it was thought this way, as at the time anything that was bad was the fault of the Jews.”

He only discovered his Jewish roots through his wife, who was also raised as a Catholic, and at some stage began suspecting that she had Jewish roots.

The suspicion turned to certainty after a visit to Warsaw’s Jewish Historical Institute; but she returned home with a surprise for Pinchas as well. “I’ve looked up your family, and you’re Jewish as well.”

The news made unpleasant hearing for the former skinhead, who rushed to confront his parents. It turned out that his maternal grandmother had survived the war while hidden as a child in a monastery. His paternal grandfather had also been Jewish — facts that Pawel’s parents had concealed as part of the wider attempt of Jewish survivors to assimilate.

The unwelcome discovery set off a period of intense soul-searching for Pinchas, which led to a bris milah and a full embrace of Judaism — despite the hostility of his former anti-Semitic comrades.

Working today for the Jewish community in kashrus, Pinchas is an example of just how little Poland’s returnees know of their roots.

“I know that we’ve been in Warsaw for four generations,” he says, “but who my great-grandparents were and where they came from, I have no idea.”

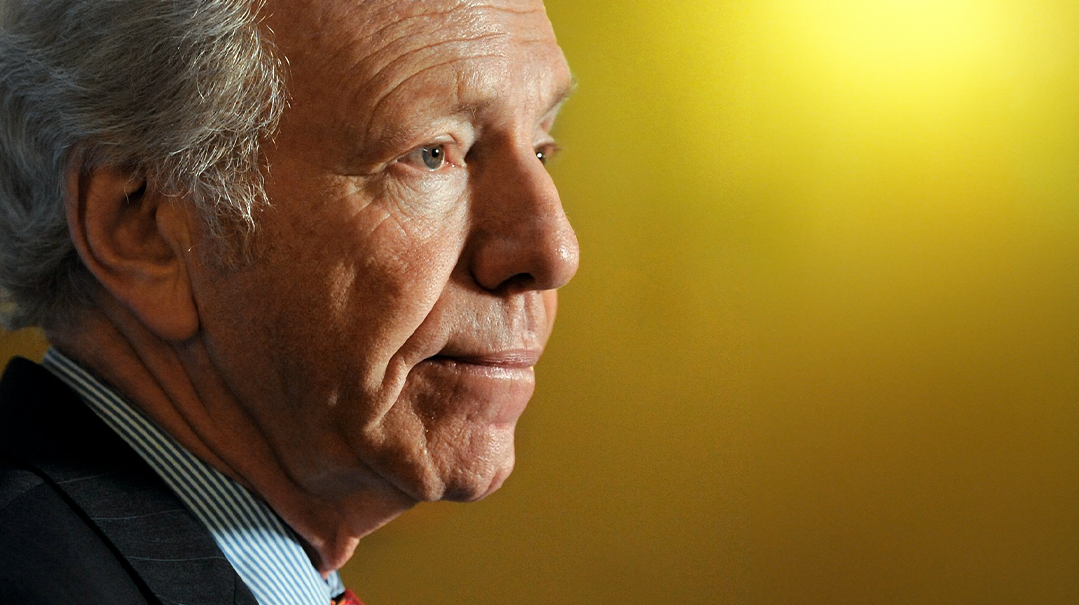

“The death camp law was foolish, but stemmed from a real grievance.” Poland’s Chief Rabbi Michael Schudrich (pointing, second left) guides a CER tour of the Warsaw ghetto

Writing History

Historical amnesia is a pathology that afflicts Poland in general: the country’s sense of itself groans under layers of memory. That’s the background to the controversy over the Holocaust, which has become a major irritant in the Israeli-Polish relationship over the last few years.

It all began back in 2018, when the Polish government passed a law penalizing any attempt to blame the Polish people for war crimes committed by the Germans. Although the law didn’t say so by name, it became known as the “death camp law” because its aim was to end references to “Polish death camps” — a shorthand that infuriated Poles who felt that the phrase implied Polish culpability for what had been Nazi killing centers that happened to be located in Poland.

Passage of the law acted like a stick of dynamite under Israel-Polish relations. Ties between the two countries had warmed as Bibi Netanyahu increasingly saw Poland as an important diplomatic ally in Eastern Europe, whose membership of the European Union and pro-Israel slant kept the EU policy from following the anti-Israel line of some of the Western European countries.

That progress came to a halt in 2018, with the passage of the death camps law. Israeli officials from the president and prime minister down accused Poland of attempting to minimize the country’s role in the Holocaust, and both sides withdrew their ambassadors.

In 2019, the issue flared again, when Netanyahu said during a summit in Warsaw that “Poles cooperated with the Nazis” during the Holocaust. In response, the Polish prime minister pulled out of a planned trip to Israel.

Things took another turn for the worse in 2021, when Poland’s legislature passed a law effectively cutting off any future restitution to the heirs of property seized by the Nazis during the Holocaust. In response to the legislation, Israel’s then foreign minister Yair Lapid called it “anti-Semitic and immoral.”

The freeze in relations coalesced into an unprecedented Polish ban on Israeli high school trips to the country’s concentration camps, saying that the program didn’t do enough to shed light on Poland’s own victim status in the war.

A recent agreement between the two sides creates an extensive list of wartime sites — both Jewish and Polish — in a non-binding list from which high school groups have to select to visit. The agreement has for the meanwhile papered over the divisions between the two sides.

As Poland’s chief rabbi with the ear of the country’s senior politician, Rabbi Schudrich has walked a fine line, effectively blaming both sides for the crisis.

“The law that was passed in 2018 was a foolish and bad law,” he argues, “but it stemmed from a real grievance shared by both left and right that Poland was being unfairly blamed for crimes it didn’t commit in the war.

“There was certainly anti-Semitism here, and that shouldn’t be hidden, but neither should the fact that unlike in France, Holland, and other countries, Poland was the only place where there was no official, high-level collaboration or creation of a quisling regime. Besides the so-called ‘Blue Police’ units who did terrible things at a local level, the Germans simply didn’t trust the Poles enough to give them power.”

Ultimately, says Rabbi Schudrich, politicians in both Israel and Poland were responsible for the tension. “To focus exclusively on the role of the Righteous Gentiles as if there were no anti-Semitism, or on Polish complicity as if there were no Righteous Gentiles — both are wrong. Politicians everywhere need to get elected, and it was in the interests of figures on both sides to make this into a big issue for their own reasons.”

Mila 18, site of the Jewish underground’s HQ bunker

Pride And Shame

The “both sides” argument ignores the fact that an undercurrent of nationalism — and a move away from liberalism — was the context of the death camps law. The governing Law and Justice party (PiS) that took power in 2015 is conservative and has moved to restrict abortion and to trammel the power of the courts — leading to tension with the European Union, whose largesse has powered a Polish economic revival.

Law and Justice policy has focused on promoting a “pedagogy of pride” about Polish history, as opposed to a “pedagogy of shame” that highlights Polish complicity in events such as the 1941 Jedwabne Pogrom, when Poles massacred hundreds of Jews.

It’s for that reason that Conference of European Rabbis president and former Moscow Chief Rabbi Pinchas Goldschmidt is less inclined to go in for the “both-sides” argument.

“What’s fascinating is to what extent Holocaust memory is central to Polish politics,” he says. “Why is it important enough as a national issue for revisionism to be part of the governing party’s platform? It’s because the search for exoneration is important for Poland’s citizenry.”

But unlike in much of Europe, where liberalism eventually led to an airing of Holocaust-era dirty laundry, the process hasn’t happened in Poland.

“I come from Switzerland,” he says, “and back in the ’90s, there was the controversy over the Swiss banks’ role in keeping the money of the Holocaust victims. The older generation wanted to keep the lid on the issue, but there was pressure from a younger generation to come clean, and eventually the banks did so.

“That process hasn’t happened in Poland. Driven by national pride, young people are not ready to say that their grandparents were wrong. In a sense, the direction of travel is the other way, as liberalism takes a back seat to nationalism. That’s because part of the ideology of the far-right is not to open up the books on the past.”

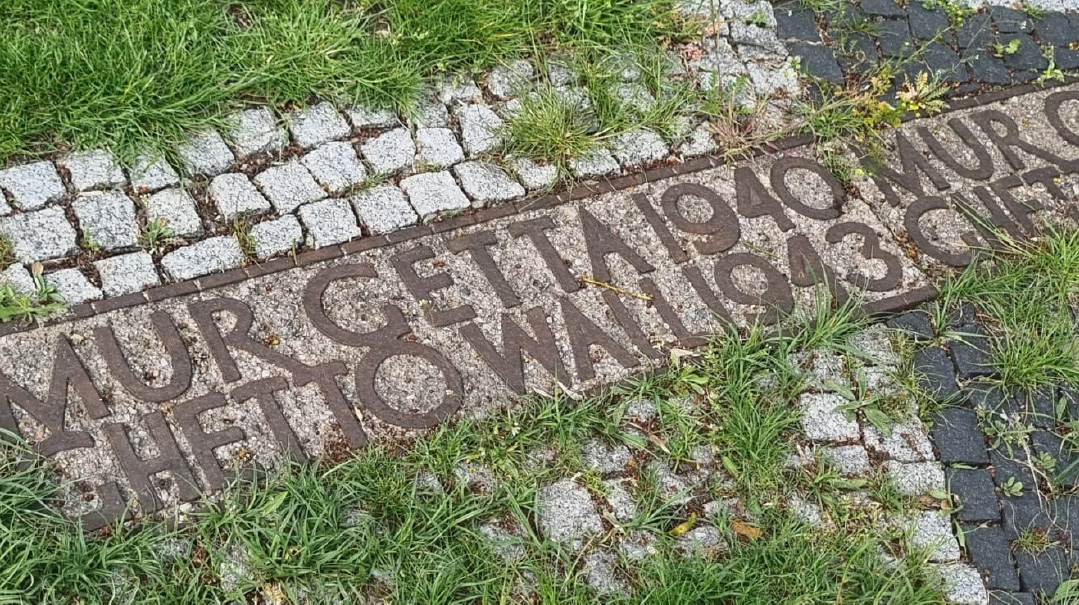

SCATTERED REMAINS The outline of the ghetto wall visible on Okopowa Street

Buried Past

Walking the streets of Warsaw, the city’s intensely Jewish past is both everywhere and nowhere. A main avenue that bisects the city center is Aleje Jerozolimskie, or Jerusalem Street. Named after the village built on the spot for Jewish settlers in 1774, it’s testament to the city’s rich Jewish past.

But in the streets of what was once the Ghetto, there’s nothing so much as a sense of what isn’t. Although there are memorials at points scattered throughout the area, there is no real sense of the enormity of what happened there.

The residents live in what was essentially a concentration camp, yet that hasn’t prevented parts of the area becoming a leafy, comfortable district. Much of the large area that housed half a million Jews in inhuman conditions is yuppified.

Modern condos that wouldn’t be out of place in Miami are surrounded by gardens, interspersed with the small grocery stores, hair salons, and other signs of normal civilization.

Much of that has to do with the fact that Warsaw was so totally destroyed. But there are remnants. On Stawki Street — a wide boulevard with a tram running through it — sits the building used by the SS to supervise the adjacent Umschlagplatz, the assembly point from which a quarter-million Jews were sent to Treblinka.

Across the road, as a sign on the building notes, is the former Jewish school and hospital where Jews were held before being shipped off to death.

In the pavement along Okopowa Street — which was the northwest Ghetto boundary — there’s a small section of sidewalk comprised of stones from the ghetto wall.

And once again, there are signs of dueling historic narratives. The iconic Warsaw Ghetto monument is one such focal point: Its portrayal of the fighters as muscled warriors is of a piece with the postwar Israeli narrative that lionized the courage of those who’d stood and fought, placing “gevurah” alongside “Shoah” in the official memory of the Holocaust events, and entirely omitting any mention of the spiritual heroism of those who endangered their lives to keep the Jewish flame burning in the Ghetto.

Alongside that famous monument is a smaller carving that is part of the Polish memory of the events. It’s dedicated to the “Zegota” — the underground Polish resistance organization that worked to save Jews and alert the world to the killings.

Further along, next to the massive new POLIN museum dedicated to Polish Jewish history is another inscription that seeks to place the Ghetto uprising in the context of Polish resistance — that, despite the fact that due to anti-Semitic animus, armed Poles didn’t rush to help the outgunned Jewish fighters.

In a theme that has present-day echoes with the creeping universalization of Holocaust memory, the plaque unveiled in 1946 is notable for its attempt to lend this most Jewish of struggles an all-inclusive aspect, reading:

“For those who fell in an unprecedented and heroic struggle for the dignity and freedom of the Jewish people, for a free Poland, and for the liberation of mankind.”

The SS headquarters on Stawki Street are some of the only surviving remnants of the ghetto’s existence

Left with Memories

In the eight decades since the Nazis razed the Warsaw Ghetto, a new city has risen atop the ashes of the old — in many places, literally so.

Mila 18, the bunker and command post of the ZOB, the Jewish combat organization that fought the Nazis in the uprising, is a famous landmark, commemorated with a red-and-white wreath sent to mark the anniversary by the Polish government.

Standing atop the gentle knoll that holds the memorial, a view of the adjacent plot shows a large white tent over an excavation site. While laying the foundations for a new apartment block on Mila Street, authorities found remnants of what is thought to be another bunker, this one still containing human remains.

It’s symbolic of the fact that — perhaps inevitably — so much of this country’s Jewish presence is really about the past.

“Ronald Lauder once told me the story of how when his organization first came to Poland 40 years ago, they made a gathering for a few hundred people who were suspected to have Jewish roots,” says the CER’s Rabbi Pinchas Goldschmidt.

“The organizers tried to awaken some early Jewish memories of these old people, and so they sang Yiddish lullabies, like ‘Rozhinkes mit Mandlen’ and ‘A Yiddishe Mama.’ It took a while, but after a few minutes, those childhood memories emerged and many began to sing along.”

That painstaking work of trying to coax lost Jewish souls out into the open is ongoing at the Nozyk shul and across Poland, but it’s against a background that is overwhelmingly about the past, not the future.

“What’s so sad about Poland,” finishes Rabbi Goldschmidt, “is that unlike other post-Holocaust countries with large Jewish populations and schools, the discourse is a mix of past and future. Here it’s about death, about the past — in Poland, we haven’t overcome the Holocaust.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 960)

Oops! We could not locate your form.