The Rebbe’s Secret Weapon

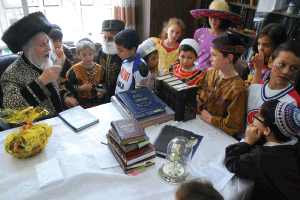

(photos: Rabbi Tal Zwecker, Rabbi Meir Kranzer)

I

t seems an improbable name for a chassidus. And to add to the riddle, it’s based in Raanana — an upscale city in the heart of Israel’s Sharon Plain — an enclave of professionals and high-tech executives. Most of its inhabitants aren’t religious, and the minority who are don’t appear to be typical candidates to join in the weekly tish.

Yet it’s there in Raanana that the Clevelander Rebbe reigns.

To one familiar with the sacred path chosen by Rav Mordechai of Nadvorna (Reb Mordche’le) and his many descendants, it’s no riddle at all. It wasn’t just back in the heim that the tzaddikim of this dynasty fanned out, across Hungary, Romania, and Galicia; it was also in America.

They left Williamsburg and the Lower East Side behind, choosing places like Newark, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia.

The Clevelander Rebbe, Rav Yitzchak Eizik Rosenbaum, is a son of Rav Yissachar Ber of Strozhnitz. His rebbetzin is the daughter of Rav Meir Isaacson of Philadelphia, a brilliant talmid chacham and author of Teshuvos Mevaser Tov. Both are grandchildren of Rav Issamar of Nadvorna and descendants of Reb Mordche’le.

This elderly couple is chassidic aristocracy, yet they’ve made it a point, from the very beginning, to transmit their holy mesorah quietly and humbly, reaching Jews one at a time.

When the Rebbe was a young immigrant from Romania, he became close to the Klausenberger Rebbe, who had settled in Williamsburg after the war and built a yeshivah there; he then went on to learn in Torah Vodaath and received semichah from Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky and Rav Yonason Steiff.

After their marriage in 1961, the new Rav and Rebbetzin settled in Long Beach, but a fire soon consumed the small beis medrash the Rebbe had established on Long Island. A delegation of Cleveland Jews heard that the illustrious young man was contemplating a move and hastened to invite him to their city, but the young Rebbe wasn’t sure he was ready to venture forth. He wanted to be in an established frum neighborhood with mosdos and shuls for a bit longer. His father, Rav Yissachar Ber, assured him that Cleveland was a “heimeshe city.”

So they went.

For 13 years, the Rebbe and his rebbetzin manned an outpost of Nadvorna chassidus in the cold Midwest. Through that decade, a most frenzied and tumultuous era for young secular Jews, the Rebbe provided answers, warmth, and direction to students and secular Jews, his rebbetzin providing nourishing meals and comfortable accommodations.

They created a flourishing kehillah, and it seemed that Cleveland had its rebbe, and the Rebbe had Cleveland.

But then in 1970, Rav Issamar of Nadvorna, shared zeide of both the Rebbe and Rebbetzin, left America and settled in Eretz Yisrael in the Yad Eliyahu neighborhood of Tel Aviv. Before his petirah in 1973, Rav Issamar encouraged his grandson to move to Eretz Yisrael as well.

They were honored to follow the Zeide’s directive to move, difficult as it was to part from their chassidim in Cleveland.

Until recently, the Rebbe would visit the kehillah in Cleveland each year, but he no longer has the energy to travel; still, his chassidim are in constant touch with him via phone and through personal visits. When the sons and daughters — and more recently, the grandchildren — of those families come learn in yeshivah or seminary in Eretz Yisrael, they adopt the Rebbe and Rebbetzin as surrogate grandparents.

He’ll Help You Build

Before starting to build his mosdos, the Rebbe needed approval from his rebbe — his own father. Rav Yissachar Ber visited Eretz Yisrael for the cornerstone laying and walked around the empty plot of land where his son hoped to establish a court. “Tatte, where will I get the money to carry out this grand plan?” the young Rebbe wondered.

“Hashem will send you someone who will help you build,” Rav Yissachar Ber replied.

Three days later, a man named Avraham Yitzchak Sondak came to speak with the Rebbe. The Rebbe felt that this was the “someone” his father had referred to, and he asked his visitor to fund the beis medrash.

Two days later, Avraham Yitzchak returned to the Rebbe with an offer to donate the shul.

And now over four decades later, as the Rebbe welcomes me to his living room — the air rich with the smell of old books and heavy with the energy of ahavas Yisrael — I open the conversation by asking: Why Raanana?

“A Jew must live with a sense of being invested in his brother’s fate,” the elderly Rebbe states emphatically. “Without true ahavas Yisrael, it is impossible to succeed. Where can a person be mekarev Jews who are far removed from Yiddishkeit today? In Bnei Brak? In Meah Shearim? Hashem sent me here over 40 years ago, as soon as I came to the Holy Land. Since then, every time I thought about moving, I received signs from Heaven that I should remain here. So if Hashem wants it to be this way, then this is the way it will be.”

Don’t Lock the Door

Our conversation takes place against the backdrop of several terror attacks in this upscale Tel Aviv suburb in the past months, including the well-publicized incident where a terrorist who knifed two people on Ahuza Street was subdued in part by a civilian with an umbrella; and the Shabbos afternoon attack, when a terrorist stabbed two people, tried running into a shul and then a private home, and was finally captured.

That Shabbos afternoon, sirens pierced the air on Rechov Har Sinai where the Rebbe lives. Shabbos was coming to a close as the Rebbe was seated at the end of a long table in his home together with a group of men attending his Seudah Shlishis. Some of them wore shtreimels and others sported knit yarmulkes, the sort of gathering typically found in the Rebbe’s company. Although the Rebbe usually holds his Seudah Shlishis in his beis medrash, that week the shul, situated below street level, had become flooded on Friday night. The chassidim removed the aron kodesh and the sifrei Torah were transferred to the second floor of the Rebbe’s home.

As the stirring melody of “Bnei Heichala” enveloped the room, a 20-year-old terrorist from Jenin had just stabbed a couple in their 40s in Ha’aliyah Park on Rechov Anilevich, which is adjacent to Rechov Har Sinai.

A frightened passerby burst into the Rebbe’s home. Where else would a person flee at such a time? “There’s been a stabbing on Anilevich!” he shouted.

“Lock the door! Keep the terrorist out!” one of the guests exclaimed.

The Rebbe turned his compassionate gaze to the man who had spoken. “Do not lock any doors,” he ordered. “When Jews sit together at this holy time and their souls attach themselves to the Upper Worlds, no destructive force is capable of harming them.”

Seudah Shlishis continued. The Rebbe sang songs of yearning, explained the mystical meaning of Yaakov Avinu’s descent to the exile in Egypt, and, together with listeners, tightly grasped the final moments of Shabbos. He was spreading a protective blanket over his city.

Later that evening, the news reported that the terrorist had attempted to enter a shul and then tried to massacre a family on a street nearby after entering their home through a ground-floor window. He was thwarted by the quick-thinking woman of the house, who shoved him out and locked the window and door behind him. He was caught minutes later in the yard by police.

One Body, Many Limbs

The Cleveland chassidus in Raanana is not the place to go if one is looking for chassidim pressed together on rows of bleachers, straining for a glimpse of their revered leader. This chassidus has no elegant external trappings — its beis medrash is identified by a simple sign in old-fashioned script hanging on a wall of bare cement on Rechov Har Sinai: it gives a visitor the impression that time is standing still.

And in a way, it is.

For over four decades, the Rebbe and the Rebbetzin have lived on a holy cloud. Yet aware that theirs is not a chassidishe locale, the Rebbe advises his own chassidim to move elsewhere if they hope to raise chassidishe children who will remain on the path of their forebears.

“Before I settled in Eretz Yisrael,” the Rebbe relates, “I wanted to by a building for a beis medrash in Yerushalayim. I paid for it with a check, but the check was sent back to me several months later. In the interim, another buyer had come and had offered a higher price. The seller thought that I would raise my own bid, but I didn’t. I saw it as a stroke of Hashgachah.”

About 20 years ago the Rebbe established a large beis medrash in Beitar Illit, which is led by his son Rav Uri Rosenbaum, but meanwhile the Rebbe has continued to carry out his mission in Raanana.

“When we first came here, there was only one kollel in the city. I told the person who had invited me here, Reb Michel Wahrman, head of the religious council, that I planned to open a kollel.

“He raised an eyebrow. ‘There is already a kollel here. Can Raanana sustain two kollelim?’

“I replied, ‘The day will yet come, Reb Michel, when Raanana will have 12 kollelim for avreichim.’ Today, with thanks to Hashem, there are more than a dozen kollelim in Raanana — some chassidish, some litvish, and some Sephardic. Baruch Hashem, Jews are living here and learning Torah. Can there be anything greater than that?”

I comment to the Rebbe about the difficult security situation and ask how we can strengthen ourselves in light of the current wave of violence. “In my opinion, everything that is happening now is a result of the fact that we are not making sufficient efforts to inspire other Jews to do teshuvah,” the Rebbe responds. “Baruch Hashem, we have many ways today to be mekarev other Jews. Sometimes we wonder why Hashem hasn’t sent Mashiach yet. Yet every Jew has an obligation to connect himself to others. After all, every person has 248 organs. Is a person conscious of his little finger? No. But if that finger is hurt, then will he be aware of it? Absolutely. He will cry out in pain, and he will do everything possible to heal his wound. And the same is true here: The Jewish People are like a single body. It doesn’t matter if a person is chassidish or litvish, Sephardic or Ashkenazic, chareidi or chiloni. We are all part of one body, and our obligation is to unite all the parts of that body.”

Still, many people among us maintain that due to all the negative influences around us, now is the time for strengthening the barriers that protect us from the outside world, rather than working to spread the light of Yiddishkeit to others. The Rebbe says it’s not a contradiction. “I myself have sent people away from Raanana when they grew and became true chassidishe avreichim. My talmidim have moved on to Ger, Vizhnitz, Belz, and other prominent chassidic communities. Is it possible for an avreich who wants to raise chassidish children to live in Raanana? In all likelihood, it is not — but in no way does that contradict the obligation to be mekarev every Jew. There is a rule in the laws of melichah that something that is tofeiach al menas l’hatpiach — moist enough to make something else wet — does not absorb blood. The same is true here: When a person approaches another Jew with the goal of drawing him close to the Torah, and he is equipped with the requisite inner strength, there is no concern that he will be affected by foreign influences.”

Rabbi Tal Zwecker, a prolific writer and popular disseminator of chassidic teachings, is a close chassid of the Rebbe. He recalls once driving the Rebbe from Yerushalayim to Raanana and stopping for gas. At the station, the Rebbe turned to the car parked at the next pump and saw the bare-headed driver about to bite into a large sandwich.

The Rebbe held up his hand. “Wait,” he called out to the alarmed driver. “Are you Jewish?”

The driver warily conceded that he was.

The Rebbe removed his own wide-brimmed felt hat and handed it to the driver. “Here, a Jew doesn’t want to eat without first making a brachah. Take my hat and let’s recite the blessing.”

A Rebbe who can offer a rebbishe hat to a secular Jew is one who can plant spiritual life in Raanana.

Under Siege

The Clevelander Rebbe was born 85 years ago in the town of Strozhnitz, Romania. His father, Rav Yissachar Ber ztz”l, the Rebbe of Strozhnitz, was the son of Rav Issamar of Nadvorna, who was the grandson of Rav Mordche’le, founder of the Nadvorna dynasty. The Rebbe spent his childhood in the company of his father and grandfather, immersed in diligent Torah study and the purity of his chassidic upbringing. The idyllic period ended, though, when black clouds of turmoil covered the Romanian skies.

When the German army swept through Europe, Romania was ripe for conquest. The smaller anti-Semitic parties in the country supported the Nazis’ agenda enthusiastically, and hundreds of thousands of Romanians joined the cause, as the newspapers were filled with anti-Semitic articles inciting the masses to violence. King Carol II was forced to abdicate and to leave the country, making way for his son, King Michael I, to seize the throne, along with his divorced mother, Queen Helena. Ion Antonescu assembled a new government in collaboration with the members of the Iron Guard, zealous followers of the Nazis. Thus, the Holocaust began to rage through Romania. Half of the country’s Jews were murdered while most of the others were shipped off to the death camps.

“Our city was the district capital and came under Russian control,” the Rebbe relates. “As soon as they arrived, the Russians ordered all the batei medrash and mikvaos closed. Those were the days of the Yevsektzia, who sought to destroy us spiritually. At that time, my father demonstrated incredible mesirus nefesh, building and maintaining a mikveh in the cellar of our home. He arranged minyanim and ensured that we remained steadfast in learning. This continued until the second day of Tammuz 1941, when the Germans and the Romanians began driving the Russians out of the country.

“That Tammuz,” the Rebbe continues, “the Romanian-Nazi conquest began. I remember the Nazis descending on our town like a plague of wild beasts, mercilessly slaughtering parents and children together.

“On the 8th of Tammuz, my father realized that the Russians were about to withdraw, and he became concerned that the town might be burned down. He decided to send my older brother Yosef, my older sister Shifra, and me to the home of one of his friends who lived outside the town. Indeed, that entire night the Germans fought fiercely against the Russians, who tried desperately to defend themselves. The town was rocked by explosions, and the residents feared their homes were about to collapse at any moment. By morning the explosions subsided and my father sent for us, but our host insisted that we remain a bit longer.

“On the way home, we were accosted by a young sheigetz, a Romanian youth, who began pulling my brother’s peyos. My older sister slapped the goy in the face in an effort to protect our brother. The Romanian boy began screaming that the Jewish children had attacked him, and the Romanian soldiers came after us with their guns. When we realized that the soldiers were firing on us rather than defending us, we ran away as quickly as we could. B’chasdei Hashem, we managed to get back home. But on the way, we saw a Jewish man lying in the gutter and moaning in pain. We looked at him, and we recognized him as Reb Yerachmiel Hy”d, one of the members of our father’s shul. We called out to him, and he picked up his head and saw us. ‘Children, save me!’ he called out, and then his head fell to the ground again. We ran home and were greeted by our overjoyed father, whose happiness faded as soon as we told him about Reb Yerachmiel. He ordered us to run to the Jewish hospital so they could send someone to save him, but as we ran, my brother Asher Mordechai was captured. Still, my father calmed everyone down and focused on the rescue efforts. Many miracles happened to us.

“The Nazis later erected the ghetto of Stroznovich, where we were forced to stay for several months. We moved from there to Chernowitz, which had been home to a large Jewish community. We managed to stay hidden for several weeks in a clandestine apartment, where our lives were saved several times through open miracles. During that time, my father was staying in the local hospital, but he came to join us on Chanukah in order to light the candles with us. It was a bizarre experience: Outside, Jews were being killed, but inside, a chassidish Jew was lighting the Chanukah menorah. I’ll never forget the sublime sight of my father bentshing licht in our hiding place. I remember the tears streaming down his cheeks as his trembling voice filled the room.

“We spent seven weeks in that hiding place, until we had no choice and joined the other Jews in the ghetto. During that time, my father made many sacrifices to keep the mitzvos and persisted in walking in the streets with his beard and peyos, urging us to do the same. Baruch Hashem, our entire family was saved — both parents and children.”

Living Legacy

At the end of the war, the Rosenbaum family traveled through Europe, spending a few weeks in Radoshitz and then moving to Bucharest in 1946. “Our father rented a two-room apartment there,” the Rebbe recalls, “and opened a beis medrash in the apartment. We spent two and a half years in Bucharest, until we moved to America in 1948. We all traveled together — our entire family, including our grandfather, Rav Issamar of Nadvorna — on the ship to New York. At first, we lived in the Bronx, and then we moved to Boro Park.”

Why was it the practice in the Nadvorna dynasty for the sons of the rebbes to serve as admorim while their own fathers were still alive?

“The Zeide, Rav Mordche’le, instructed his children to assume positions of leadership during his lifetime, commenting, ‘The world will see that Mordechai knew best.’ All of his six children, including my grandfather, became admorim during his life. Both my father and his brother, Rav Chaim Mordechai of Nadvorna, followed suit and served as the leaders of chassidic communities during their father’s lifetime.”

In a city like Raanana, the importance of making a kiddush Hashem is especially pronounced.

“Certainly,” the Rebbe confirms. “A chareidi Jew, especially in a city like this one, must act in such a way that people will not speak ill of him. He must be kind and pleasant, and he must fulfill Chazal’s admonition to cause the Name of Hashem to become beloved through his actions. Throughout the years, people have tried to convince me to move to Bnei Brak or to Beit Shemesh, but Hashem has made it very clear that this is my place to sanctify His Name.”

And when the Rebbe sees a Jew being mechallel Shabbos?

“I don’t walk down the street and shout at drivers, but if I have an opportunity to talk to a Jew when I see him driving on Shabbos, lo aleinu, I say to him gently, ‘You know, it’s Shabbos today, and it is forbidden to drive on Shabbos.’ Shouting accomplishes nothing, but the soul of every Yid wants to hear the truth gently and politely.”

Lone Troops

The Rebbe has learned to fuse the different roles of the shul — chassidishe shtiebel, kiruv center, minyan hub — into one.

In Elul, Sephardic Selichos are recited in the beis medrash at night, while a separate minyan meets in the morning to recite the Ashkenazic version. The Rebbe is also faithful to his forebears’ traditions, and so davening on Shabbos is three hours long. During Sefiras Ha’omer, chassidim from various locales come to watch the Nadvorna-style avodah of counting the Omer, which takes about a quarter of an hour. During the month of Elul, the Rebbe has the custom of reciting the perek of “L’Dovid Hashem ori” when the aron is opened for the Torah reading; the Rebbe reads each pasuk aloud, and the congregation repeats it after him. It’s a bit of a lengthy procedure, but it’s suffused with a chassidic intensity that is not unwanted even in the “modern” city.

“Sure, there are some people who are deterred from coming here on Shabbos by the length of the tefillos,” the Rebbe relates, “but the minhagim of my forefathers take precedence. I would daven with only ten men in order to maintain those customs, but in the end, people feel the emes.”

In the chassidic yeshivah world, a Shabbos with the Clevelander Rebbe is considered a sublime experience. Thousands of bochurim have visited here over the years, drawing profound inspiration from their encounters with the Rebbe. The Rebbe’s Kiddush — which takes close to 20 minutes — is one highlight. “It feels like the world is reaching its climax, like Creation is being completed as the Rebbe says the words,” says a chassid who comes to the Rebbe for Shabbos at least once a month.

An no one wants to miss Shabbos Parshas Va’eira with the Rebbe, the annual Shabbos Hisachdus for Clevelander chassidim from all across the country. It’s the Shabbos the Rebbe has yahrtzeit for his father, and the local residents already know that on that Shabbos, hundreds of chassidim will converge on the neighborhood. They don’t live in Raanana, this younger generation of Clevelanders, for their Rebbe has sent them forth; but on that Shabbos two months back, they came out in force and lit up its streets, bringing a sense of calm and normalcy to a city that’s been feeling itself under a terror siege since the newest wave of Arab violence.

To the Rebbe, the events of these past weeks — the terrorism just outside his window and other recent stabbings on the streets of his city — haven’t changed anything.

“A person has to live with an awareness of HaKadosh Baruch Hu, to feel Hashgachah pratis. Nothing happens by itself. No bullet can be fired unless it was decreed in Heaven. We must beseech Hashem to save us from the birthpangs of Mashiach, but at the same time, we must not forget the primary way to accomplish that: by awakening our lost brothers to engage in complete, genuine teshuvah.”

The Rebbe looks out the window at the Raanana street scene, at his brothers of all colors and stripes. “That is what we can do during times like this — love all Yidden and seek to draw them close.”

And he smiles, this Rebbe who sends his chassidim elsewhere yet remains heroically in place with only his rebbetzin at his side — the generals fighting a battle without troops.

“We live in Raanana. We do our mission here.”

—Yisroel Besser contributed to this report

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 604)

Oops! We could not locate your form.