The Rabbi, the Nazi, and the CIA

Sixty years after the capture and trial of Nazi henchman Adolf Eichmann, a hidden story comes to light

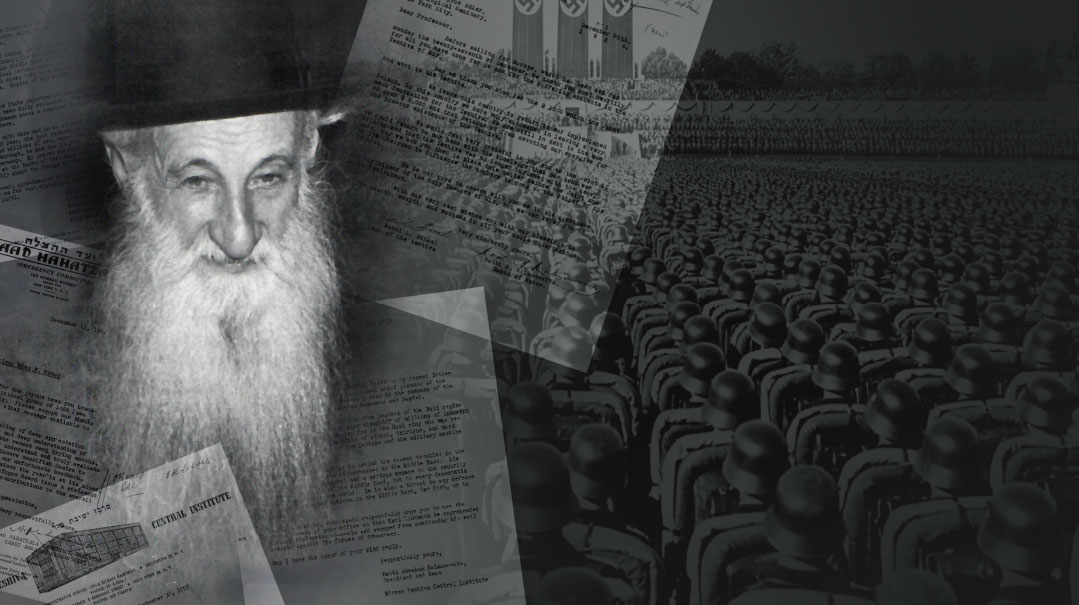

Photos: Archives of the Mirrer Yeshiva

The records of the Central Intelligence Agency are a powerful resource for any historian, and over time, the CIA’s declassified documents have helped resolve some of the great mysteries that have plagued this country as well as debunk some of its far-out conspiracies. While perusing the archive on a completely unrelated search, I stumbled upon something that stunned me. Among pages and pages of freshly declassified letters and records that had been released under the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act, were documents from the early 1950s of correspondence between Washington and the Mirrer Yeshivah on Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn. What business did a rosh yeshivah have with the US president?

On May 11, 1960, in a daring mission in Buenos Aires, Argentina, agents of the Israeli Mossad captured former SS officer Adolf Eichmann, one of the world’s most wanted Nazi criminals. Eichmann was one of the architects of the Final Solution, responsible for the mass murder of millions of Jews.

Among those who generally receive credit for bringing Eichmann to justice are Mossad Chief Isser Harel and his operatives, the (Jewish) West-German Prosecutor Fritz Bauer, Eichmann’s neighbor Lothar Hermann and his daughter Sylvia (for exposing Eichmann’s identity), and acclaimed Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal (whose role has been questioned by some). Was it possible that there was a mystery rabbinic figure who played a role in the story as well?

The first startling letter I uncovered was written in July 1953 by Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz to President Dwight D. Eisenhower. It marked the first time the US government had received a public request for information about a Nazi war criminal:

Dear Mr. President,

May I respectfully bring to your attention the following important request and I cordially urge your kind consideration of this vital matter.

An item appeared in the newspapers of July 5th that the infamous Nazi mass murderer, Karl (Adolf) Eichmann, was seen travelling on the Damascus train in the company of the notorious Mufti and the Nazi General Katzmann. Eichmann was sought far and wide after the last war by military and diplomatic agents who desired to bring him to trail for his vast crimes…

I, personally, being connected with many rescue endeavors during the war and coming in contact with living witnesses, have substantial proof about this man’s heinous acts of willful murder against untold thousands.

May I therefore appeal to you, Mr. President, in the name of democracy and human decency, to use your power of office to apprehend this mass murderer so that he may be stopped from further acts of tyranny and slaughter and cease to be a menace to freedom loving peoples everywhere….

You, who have fought the cause of freedom so valiantly, should use every effort to stop this man….

Respectfully Yours,

Rabbi Abraham Kalmanowitz,

President and Dean

Mirrer Yeshiva Central Institute

What was this? Was the great Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz ztz”l a Nazi hunter? Did the American government take his request seriously? Did he have some special in with the president? As I read through more of the file and did some additional research, a clearer story began to emerge.

Unstoppable

Back in 1926, Rav Kalmanowitz, then rav in Rakow, Poland, was approached by an old acquaintance from Slabodka, Rav Eliezer Yehuda Finkel, requesting his assistance with the dire financial straits of the Mir Yeshiva. The two paired together for a fundraising mission to the United States, resulting in Rav Kalmanowitz being appointed president of the yeshiva and tasked with the responsibility of carrying its large financial burden.

The interwar period also saw Rav Kalmanowitz’s increasing involvement with the Vilna-based Vaad Hayeshivos alongside Vaad head Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzinski; in addition, he served on the rabbinical board of Agudath Israel in Poland.

With the outbreak of World War Two in September 1939 and Eastern Poland falling under Soviet occupation, the threat of Soviet aggression against all religious institutions gave impetus to many yeshivos — including the Mir — to escape to independent Lithuania.

With the Mir Yeshiva fleeing as refugees to Vilna in October 1939, Rav Kalmanowitz was once again called to action. The desperate plight of the refugees compelled him to act in his capacity of shouldering the financial burden of the yeshivah. In January of 1940, having the rare luxury of a US passport, which he’d been able to obtain during his extended fundraising stays in the 1930s, Rav Kalmanowitz was dispatched to the United States in order to raise more desperately needed funds — a trip that would ultimately save his life and his family.

Although ostensibly on a mission to fundraise for the Mir, he threw all of his vast energies into rescue work. Joining the Vaad Hatzalah, he soon became a driving force in its lifesaving rescue operations, both throughout the war and in its immediate aftermath.

Almost single-handedly, he arranged for the transport and rescue of the entire Mir Yeshivah from Vilna, Lithuania to Kobe, Japan, and eventually Shanghai. When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the yeshivah found itself in an enemy country and was unable to receive a large portion of the funds earmarked for it by the JDC and other relief groups. Rav Kalmanowitz then began to utilize the Vatican and neutral countries like Switzerland and Sweden, creating his own transfer network that was able to sustain the yeshivah until the State Department was persuaded to permit such transfers.

In August 1942, the Polish underground sent news to leaders in Switzerland regarding the first mass deportations of Warsaw Jews to extermination camps. Among the recipients of the reports on the mass extermination of Polish Jewry was Dr. Julius Kuhl, a Jewish diplomat stationed in Bern, Switzerland. Once he read the report, he sent it on to Recha and Yitzchak Sternbuch, the Vaad representatives in Switzerland who forwarded it on to Rabbi Kalmanowitz. Upon receiving the cable, Rabbi Kalmanowitz stood up and exclaimed “Azoi?!” [“Really?!”] He said it repeatedly, louder and louder, until the terrible facts became too much for him and he fainted.

As news regarding the fate of European Jewry grew bleaker, the Vaad Hatzalah expanded the scope of its activities, undertaking even more audacious rescue attempts. A colleague of Rav Kalmanowitz wrote at the time that “nothing stood in his way during that period. When it was a matter of rescue, he repudiated all normal channels. There were no rulers, ministers or honorables, no wealthy men and no important ones. The law of the land did not exist. On more than one occasion, he committed genuinely criminal offenses in order to save a Jewish life . . . He could not understand all those whose minds were filled with endless reckonings.”

Government bureaucracy — and occasionally, even the law — didn’t hinder his rescue work. Recognizing that the clock toward total annihilation was clicking, he utilized obfuscation, flattery, and even bribery, stopping at nothing to reach his goals. He once caused himself to faint at the feet of Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau in an effort to convey the gravity of the situation. (He succeeded.)

In the spring of 1944, the Nazis commenced with the massive deportation of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz. The Working Group in Slovakia, the Relief & Rescue Committee in Budapest, the Sternbuchs (the Vaad Hatzalah representatives in Switzerland) and other rescue organizations attempted to negotiate with the Nazis to ransom Jews and perhaps even halt the deportations. Rav Kalmanowitz was willing to take any desperate measure of rescue and was heavily involved in the fundraising toward these rescue efforts. He was also a vocal proponent in demanding that the Allied Forces bomb the railway lines and the crematorium facilities at Auschwitz.

Never ceasing in his rescue efforts, he also continued to maintain the Mir Yeshivah in Shanghai until the war’s end. Following the war, he waged a tireless bureaucratic campaign to enable the Mir students and faculty to immigrate to the United States. He was ultimately successful, and by 1947, the last Mirrers had arrived.

Even after the war, Rav Kalmanowitz didn’t take a break. He founded and stood at the helm of the Mirrer Yeshiva Central Institute in Brooklyn until his passing in 1964, and remained involved in myriad projects to further Jewish education until the very end. He spent much of his post-war years galvanizing an effort to save the Jews of Egypt, Syria, and Morocco, who were being persecuted in their native lands. Together with Mr. Isaac Shalom, himself an immigrant from Syria, he founded the Otzar HaTorah organization to assist the endangered Sephardic communities around the world, both physically and spiritually. He is one of the figures credited with helping to build the thriving Syrian community in Brooklyn, which many years later returned its gratitude by helping to expand the Mirrer Yeshivah, situated in the heart of the Brooklyn neighborhood where many of them reside.

Sorry, No Help

By the 1950s, so many years of tireless activism meant Rav Kalmanowitz was no stranger to the corridors of power in Washington. And as the Eichmann whereabouts saga was unfolding, there was a flurry of correspondence between Rav Kalmanowitz and US government powerbrokers.

Rav Kalmanowitz’s urgent request regarding Eichmann made its way to the State Department where Parker T. Hart, director of Near Eastern Affairs, responded on behalf of the president on 24 August, 1953. “The United States has, of course, no power to arrest an individual in another country,” Hart noted. “In any event, it is by no means clear what country Eichmann is now in or what he may be doing. Under these circumstances, it is not possible for this government to make any representations to any other government concerning his activities, or to take any other action in the matter.”

Rejection was never a deterrent to Rav Kalmanowitz, so his next step was to utilize his contacts to appeal to the CIA, initiating his own contact with CIA director Allen Dulles. In his letter to Dulles, he referred to his involvement in the negotiations between Swiss politician Jean-Marie Musy and the Nazis, in coordination with the Sternbuchs, to rescue large numbers of Jews (Musy was involved in the release of 1,210 prisoners from the Theresienstadt concentration camp).

Around the same time the letters were being exchanged, articles began to appear in newspapers claiming Eichmann had been spotted in the Middle East. (It turns out that although those rumors were unfounded, they pushed Rav Kalmanowitz to work even harder to neutralize the Eichmann threat.)

Frustrated by the US government’s tepid response, Rav Kalmanowitz arrived in Washington on October 20, 1953, to personally meet with CIA officials. They, in turn, explained to him that as an intelligence organization, they couldn’t apprehend Eichmann for trial, and could do nothing more than note the information of his supposed whereabouts. Rav Kalmanowitz was advised to appeal to the West German government to take steps to bring Eichmann to justice.

Leads to Nowhere

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, Vienna-based Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal was experiencing his own share of frustration in his attempts to track down Eichmann. It was around the time Rav Kalmanowitz began his vigorous pursuit that Wiesenthal claims to have had his breakthrough.

In late 1953, Simon Wiesenthal met with an old Austrian count and fellow philatelist named Heinrich Mast outside Vienna, seemingly to view his stamp collection. At one point, the baron passed Wiesenthal a letter, admiring its stamps, before directing him to open the envelope. “Beautiful stamps, aren’t they?” the Baron remarked. “But read what’s inside.”

Wiesenthal’s eyes opened wide as he tried containing his excitement. The letter was written by a former Luftwaffe colonel who had never been sympathetic to Hitler and was now living in Argentina. The official was expressing his disappointment with the fact that some of the worst Nazi criminals were living their lives out in secret in South America. “Imagine who I had to talk to twice,” he wrote. “That awful swine Eichmann who commanded the Jews. He now lives near Buenos Aires and works for a water company.”

Wiesenthal now felt that he possessed the smoking gun, and he worked to assemble a full case file on Eichmann. He then shared the findings with Ari Eshel, the Israeli consul in Vienna, hoping that the Israeli government would help fill in the missing pieces and provide the resources and manpower to capture Eichmann and bring him to justice.

Several months later, Eshel informed Wiesenthal that the Israeli government was not ready to pursue the lead, citing the fact that most of the similar clues they’d received in the past had led them on wild goose chases that went nowhere. Disappointed, Wiesenthal moved on to the next best option: Nahum Goldmann, the powerful leader of the World Jewish Congress, and someone who clearly had the ear of Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion. But a distracted Goldmann was equally uninterested in Wiesenthal’s dossier, gladly passing it on to Rav Kalmanowitz, whom he knew was also pursuing Eichmann’s whereabouts.

Rav Kalmanowitz then began to correspond directly with Wiesenthal, asking if he had an address where Eichmann could be found in Buenos Aires. Not having all the specifics, Wiesenthal replied that it would be possible to send someone to Argentina to obtain all of the proofs necessary for $500. For the next few months, through autumn of 1954, they exchanged letters, but no real progress was made by either side. Ultimately, Wiesenthal would say that Rav Kalmanowitz was the only one who had ever attempted to substantiate his claims and sadly, it seemed to him that nobody else was even looking for Eichmann.

At the same time, Rav Kalmanowitz continued in his efforts to arouse the American officials from their slumber. In early May, he wrote to Assistant Secretary of State Henry A. Byroade (who would be named US Ambassador to Egypt the following year), broadcasting his warnings about the threats posed by the Arabs, and his suspicion that Eichmann and his cronies were behind them.

Though the CIA wasn’t being very helpful, the continuous correspondence from the “Brooklyn Rabbi” and his Middle East leads spurred the agency to conduct its own investigation. Most responses were negative, but there was at least one claim that Eichmann was in Syria in 1951. In early 1954, a CIA memo reiterated, “While we are interested in the whereabouts and activities of Eichmann, it is not within the CIA’s jurisdiction to take any action in connection with his status as a war criminal.”

As it turned out, all leads to Eichmann being in the Middle East were proved to be completely false.

Shock and Capture

Ultimately, with the Cold War presenting challenges and guiding US foreign policy at the time, the CIA and the State Department were less than motivated to dredge up the evils of the past. Coupled with this was the fact that West Germany — whose government was staffed by no small number of former Nazi criminals — was a US ally and a buffer against the Soviet Bloc. The prospect of an extradition and a high-profile trial of Eichmann was therefore not at the top of anyone’s agenda at this juncture.

By the mid-1950s, the CIA’s interest in Eichmann diminished, until the news of his abduction from Argentina by the Israelis in May 1960. In perhaps the most famous trial of a Nazi war criminal, an Israeli court convicted Eichmann of crimes against humanity and sentenced him to death by hanging, which was carried out in 1962.

World leaders expressed shock that leading Nazis had somehow escaped the postwar trials. In Washington, the CIA was taken by surprise by the Israeli action, and sent a cable to Berlin requesting an immediate check on Eichmann’s records.

This short-lived saga was a valiant attempt on Rav Kalmanowitz’s part to bring to justice those perpetrators of genocide during the dark years of the Holocaust. Did his efforts ultimately play a role in the actual capture of Eichmann and other Nazi fugitives? The honest answer? Probably not — but there is so much more to be learned from the effort.

The idea that the halls of power were impenetrable or that any mission was unattainable didn’t figure into the thinking of Rav Kalmanowitz and other great heroes of the time. For these men — Vaad Hatzalah giants such as Irving Bunim and Stephen Klein, and rabbinic greats like Rav Aharon Kotler and Rav Eliezer Silver — knowing that they were shluchei mitzvah and that the fate of their brothers was in their hands meant that they couldn’t let the seemingly most insurmountable obstacles stand in their way.

Based on sources including the records of the CIA, the DMS Archives of the Lithuanian Yeshivos, Richard Breitman’s Hitler’s Shadow: Nazi War Criminals, U. S. Intelligence, and the Cold War, Neal Bascomb’s Hunting Eichmann and The Nazi Hunters, David Kranzler’s Thy Brother’s Blood: The Orthodox Jewish Response During the Holocaust, and Tom Segev’s Simon Wiesenthal: The Life and Legends.

HER FATHER’S QUILL

The recent passing of Rebbetzin Reichel Berenbaum has sparked renewed interest in her involvement in the work of her illustrious father, Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz. Famously, she played a proactive role within the walls of the Mirrer Yeshiva in Brooklyn and was a dedicated partner to her husband, Rosh Yeshivah Rav Shmuel Berenbaum ztz”l.

Lesser known, however, is the role she played in her father’s endless klal activism. Inperusing the correspondence of Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz, one is struck by the question: How did this Eastern European rabbi maintain an active correspondence with the White House, the CIA, the Treasury, the Department of State and others, all in a language that he barely knew? It was his daughter Reichel, the future Rebbetzin Berenbaum, who would write his letters in English and translate the letters he received. She stood behind all of his endeavors, and it is doubtful that Rav Kalmanowitz would have been able to accomplish all that he did without her tireless efforts on his behalf.

Yehi zichrah baruch.

A KAPPARAH

One night in September 1947, Simon Wiesenthal was roused from his sleep by heavy fists pounding on his door. Two former Jewish partisans had arrived with shocking news. They believed that they’d discovered Eichmann’s hiding place. These men, like many others in the Austrian DP camp, were active traders on the black market. It was Aseres Yemei Teshuvah and the camp’s refugees needed chickens for kapparos. At the time there was still a general shortage of food in Austria and chickens were difficult to obtain. A farmer they occasionally did business with directed then to a large farm on a mountain slope near the picturesque Austrian town of Gaishorn am See, but warned them that the farm owner had been a top Nazi official and he hated Jews. The refugees thought it might be Eichmann.

It wasn’t, but Wiesenthal and the two young entrepreneurs discovered who it was: Franz Murer, known as “The Butcher of Vilna,” responsible for the murder of some 80,000 Jews. Wiesenthal submitted an official complaint to the police and Murer was arrested. In December 1948 he was deported to the Soviet Union, as Vilna had been under Soviet jurisdiction during the war. He was found guilty of having murdered Soviet citizens and sentenced to 25 years of hard labor — of which he only served seven before being released in 1955 as a result of the Austrian State Treaty.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 821)

Oops! We could not locate your form.