The Old Soldier of Gateshead

One thing, though, was clear: It was Rav Ze’ev’s radiant face and rabbinic dignity that brought that salute again and again

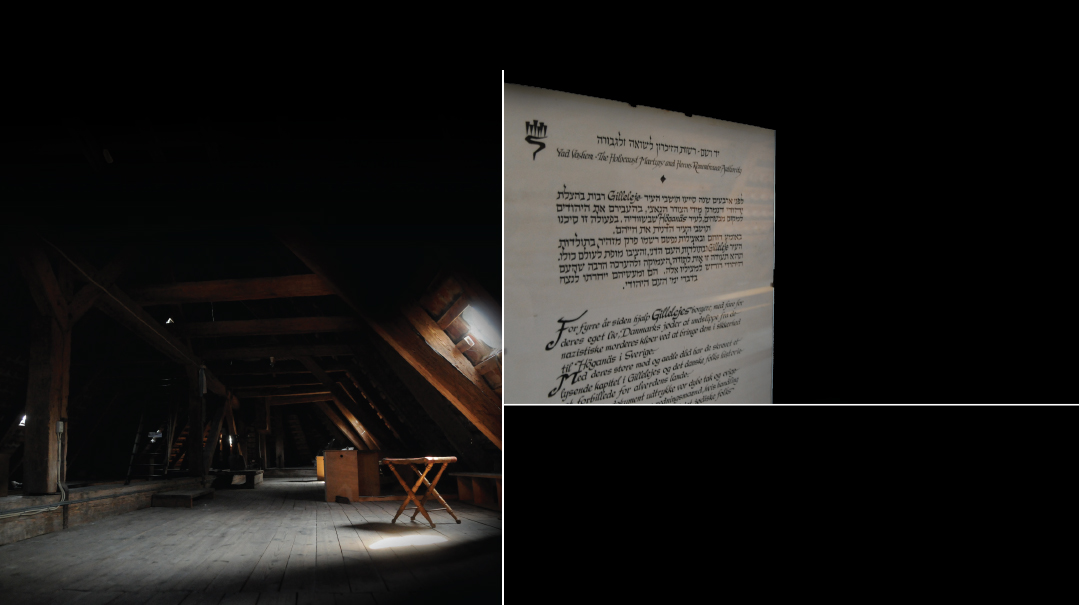

"Be outside my house two minutes after seven,” he would say carefully in his Israeli-inflected English. Grasping my hand warmly at his wooden shtender next to the aron hakodesh at the front of the Gateshead Yeshivah beis hamedrash, he would beam that radiant smile as he added in confirmation, “7:02,” and then I’d turn to go.

On his eleventh yahrtzeit, there are many better qualified than I to write a tribute to Hagaon Harav Ze’ev Cohen ztz”l, for half a century the menahel ruchani of Gateshead Yeshivah. Those tributes could focus on his famed mastery of Shas and Rambam; the mix of oratory, mussar, and stories he picked up in the Yeshivas Chevron of old; or the middos that led him to forgive those who wronged him in the course of a long public career.

But my perspective takes in none of the above. Rather, it’s that of an 18-year-old bochur who had the opportunity to observe a unique encounter. Imprinted in my memory is the image of a talmid chacham whose majesty was unmistakable to the non-Jewish residents of Gateshead.

Exactly when I began to go into “Reb Ze’ev,” as he was known, I don’t remember. The Menahel — a position that was essentially a rosh yeshivah — lived next door to the storied yeshivah on Windermere Street. There were bochurim who used to learn with him, and others who’d go into him during the afternoon seder, officially to discuss their learning, but generally to bask in the warmth of his rich personality.

This, after all, was a world-class figure who’d been shaped by many influences. Although Reb Ze’ev stood at the helm of a litvish yeshivah, his father, Rav Yechiel Fishel Cohen, was a chassidic talmid chacham from Lodz, Poland, and a leading follower of the saintly Ostrovtza Rebbe.

“He was so thin from constant fasting that he had to wear a fur coat in the summer,” Reb Ze’ev would say of the Rebbe.

And then there were his memories of Chevron. He was 15 when he joined in 1942, and the yeshivah had recovered from the massacre to flourish in its Geula location. Rav Chatzkel Sarna and Rav Aharon Cohen were roshei yeshivah, and figures like Rav Aharon Chodosh and the brothers Rav Yitzchak and Rav Boruch Mordechai Ezrachi were close friends.

“I remember once going for a walk on Erev Shabbos, without a jacket,” he said of that period, “and a car stopped. It was the Gerrer Rebbe, the Imrei Emes, and he wanted to talk to the Chevron bochurim. I was struck dumb so that I couldn’t talk.”

It was memories like these (and a break from afternoon seder) that attracted a small group of bochurim to visit, and so at some stage I found myself observing the small figure with his bright eyes and hadras panim from close up in his front room.

“I remember your elter zeide, Reb Gedalia Dovid,” he said, rolling his reish in his distinctive way. “Er iz gevein a fierdiker baal darshan,” he recalled of my namesake and great-grandfather’s oratory.

That’s how I got to observe a scene that I’ll never forget.

I discovered that Reb Ze’ev would go for a long, pre-Shacharis walk every day for health reasons. Bochurim being the night owls they are, there were very few takers for the honor of rising at 6:30. So when I asked to join the Menahel the next day, his response was one that repeated itself with metronomic regularity over the next year or two.

“A leetle — two minutes after seven,” he said.

The next day, at precisely the time he mentioned, the Menahel stepped out of the door of his house. His winter coat and Homburg were immaculate; his flowing white beard in perfect order; his scarf worn like a Victorian cravat. It was Slabodka splendor framed by a drab Gateshead street.

We walked up the steep road away from the yeshivah, crossing Coatsworth Road — with three or four shops, the commercial epicenter of Jewish Gateshead — and turned right onto Prince Consort Road. Walking awestruck by his side as he strode surprisingly quickly, and trying to keep my hat on in the Northeast’s chilly wind, I discovered that it wasn’t easy to talk to Reb Ze’ev.

The problem wasn’t making conversation; it was telling him anything new. As soon as you began repeating something from the previous day’s shiur, he would respond with a trademark flourish.

“Nu,” he’d say, as if he were still back in Chevron, “a well-known vort.”

But by the time we were halfway up the wide leafy street, past the Musgrave School, a private institution behind high gates, and Gateshead Community College, we were in full flow. Mussar, anecdotes, sharp plays on words — the Menahel’s conversation was as brisk as his pace.

Until he saw the Old Soldier.

That’s how the man remains classified in my mind. His face and dress are now hazy, but one thing remains clear. Standing outside his garden gate as we approached, was someone clearly non-Jewish — in his sixties. The arresting thing about this man was that he stood bolt upright, at attention.

As we approached, and the man remained drawn up in a salute, Reb Ze’ev gripped my hand and said in Yiddish, “I don’t know who he is, but he does that every day.”

It could have been the Changing of the Guards outside Buckingham Palace, and Reb Ze’ev reacted accordingly. As we passed the man, the Menahel of Gateshead Yeshivah quickened his pace, straightened his back and drew his hand up to his forehead, and — as if reviewing an honor guard — returned the salute.

To this day, I have no idea who the Old Soldier was. Every time we walked past over the months that I escorted Reb Ze’ev, he was there, ready to greet the dignitary. Despite the countless times the little parade was re-enacted, we never stopped to talk.

One thing, though, was clear: It was Rav Ze’ev’s radiant face and rabbinic dignity that brought that salute again and again.

It’s been years since I last walked up Prince Consort Road. Reb Ze’ev’s sayings sometimes pop into my mind, and the memory of his warmth to my 18-year-old self leaves a pleasant glow.

But more than any mussar idea that he shared is the ultimate mussar that I saw. That a man transformed by a lifetime of learning can radiate a splendor for all to see.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 877)

Oops! We could not locate your form.