The Next Dimension

3D printing can be truly life changing. One Israeli OR director has already seen people’s lives changed in unimaginable ways

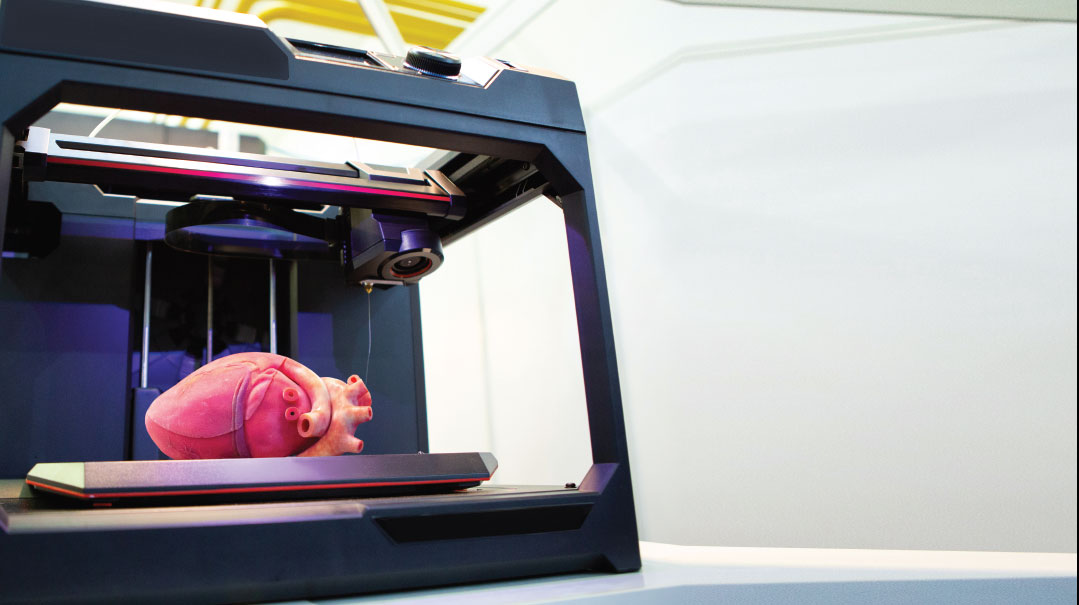

While 3D printing technology is being used in many industries, it has particular impact in the medical field. A 3D “printer” can create custom-made prosthetic limbs, specialized surgical tools, or organ facsimiles used to help doctors prepare for complex, invasive procedures. 3D printed anatomical models from patient scan data are becoming increasingly useful tools in today’s practice of personalized, precision medicine, as visual and tactile reference models can enhance understanding and communication within operating teams and with patients.

Healthcare professionals, hospitals, and research organizations across the globe are using 3D printed anatomical models as reference tools for preoperative planning, mid-operative visualization, and sizing or pre-fitting medical equipment for both routine and highly complex procedures. And Israeli hospitals, for their part, are making sure they’re in the game.

Dr. Dina Orkin, director of Sheba Medical Center’s operating rooms and of their 3D lab, says that not long after the lab was up and working, she had an opportunity to implement and experience the amazing potential of this technology first-hand. A five-year-old little fellow named Omer was stricken with Ewing sarcoma, a type of cancer that forms in bone and soft tissues. His oncologists, who had scheduled him for surgery to remove the diseased thigh bone, gave a hopeful prognosis for his survival, but it would necessitate amputation of his leg.

“This is one of the areas where 3D printing can be truly life changing,” Dr. Orkin says as she holds up a 3D-printed mold of the bone. The technology, which is also being implemented by Ichilov Hospital, Beilinson Hospital, Shaare Zedek Medical Center, and other medical centers in a country that prides itself on cutting-edge advancements, is particularly significant in the field of orthopedic oncology, whose greatest challenge is the high precision required to excise malignant bone tumor, which must be completely removed in order to prevent a relapse and metastases.

“It’s done by combining MRI, ultrasound, and CT imaging to produce a file that can be processed by a 3D printer,” she explains in layman’s terms. “In this case, we printed a mold (think cake pan) that corresponds exactly to the affected bone, filled it with surgical cement and voilà — a precise ‘custom-made’ femur, perfectly suited to the patient. After rehab, this child will be able to stand on his feet, walk, and even run. He’ll have the gift of a childhood.”

If the Shoe Fits

A little over a year ago, Sheba’s director, Professor Yitshak Kreiss, broached the idea of incorporating 3D printing into the medical landscape, convinced that it would change the face of conventional medicine, and commissioned Dr. Orkin to take charge of the project. Since then, with the cooperation of the hospital’s surgical departments and other external companies, Dr. Orkin has taken this experiment and run with it, helping to improve the surgical outcomes and quality of life of hundreds of patients.

The 3D team has “printed” various prosthetic implants, such as hip joints and knee replacements, with astounding results. Dr. Orkin believes that the future of orthopedic surgery lies with these personalized components, as opposed to those that are mass produced, and that by definition can never provide a perfect fit. “When you shop for a pair of shoes, even if you get the right size, how many pairs do you have to try on before you find the one that really fits well? And of course, we’re not talking about shoes here, but internal implants that must work in tandem with the rest of the body.

“In advance of surgery, we’re often asked to print a 3D replica of the patient’s kneecap, for example, so that the physician can get a good look inside and plan the procedure. This is especially helpful for a new surgeon who doesn’t have much experience, but in the case of more complicated procedures, even a top surgeon will prefer to get a preview and make a ‘dry run’ before the actual incision,” Dr. Orkin observes.

Forward Facing

The 3D printing lab also assists in oral and maxillofacial reconstruction, the surgical repair of defects in the face and jaw. A 50-year-old man who suffered from a severe toothache was found to have a tumor in his lower jaw, necessitating the removal of a part of the mandible. The maxillofacial surgeon used bone grafts from the patient’s leg, precisely cut with the aid of 3D-printed measuring guides that indicated the exact size and shape, as well as the angle, for the incision. Thanks to this meticulous process, Dr. Orkin says, “there’s no trial and error, no leftover bone. The pieces fit together like Lego.” And, according to Dr. Orkin, there’s no comparison in terms of outcome and recovery time. The patient experienced a relatively rapid recovery, without the impaired speech and difficulty chewing that ordinarily accompany similar procedures.

The beauty of 3D printing technology is how it dovetails with other high-tech innovations. In the case of Chana, a 16-year-old who suffered a trauma that left her face disfigured, the team was able to show her computer-generated simulations of how her face could be reconstructed, allowing her to choose exactly how she would appear at the end of the surgery. The team was then able to print the pieces exactly according to the young woman’s specifications.

Physician’s Passion

While Dr. Orkin directs Sheba’s 3D lab, her primary function is as director of all the hospital’s 39 operating rooms, with their 200 daily surgeries and procedures. That means she orchestrates all the myriad details that go into the smooth running of the operating room: managing the nursing staff, surgeons, supporting physicians, and anesthesiologists, as well as inventory and budget.

Dr. Orkin describes herself as “a doctor through and through, in my heart and in my soul.” She is married to a doctor and of her three children, one is in med school, and her high-school aged daughter spent the last summer with her mother in the OR. “I tell my children, ‘You don’t go into medicine for the money or the prestige, or to make your parents happy. You only go into medicine if you feel that this is your life’s calling.’ ”

Since early childhood, Dr. Orkin had no doubt that she would join the medical profession. “For as long as I can remember, I wanted more than anything to work in the operating room. In high school, I was able to get a job cleaning the operating rooms in a university hospital close to our home. I always felt my heart beat in anticipation whenever I passed the red line that separated between the waiting room and the doors to the OR — and I was only there to wash the floor.”

Dr. Orkin earned a specialty in anesthesiology in the ICU and for six years served as the director of pediatric anesthesiology at Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Jerusalem.

When she felt it was time to move on, Dr. Orkin switched to Sheba, where her creativity and out-of-the-box thinking were given free rein. “After close to 30 years working in different capacities in the operating room, I thought of a model that was nonexistent — to be the overall director. I had a vision for the OR that mirrors the human body, with all the organs and systems working together in harmony.”

The advantages, according to Dr. Orkin, are many. “In a multidisciplinary system as complex as the OR, there are often conflicting interests, arguments, and misunderstandings on a daily basis. Where does that leave the patient? By having one central managing hub, the needs of the patient can be front and center.”

It seems like a gargantuan task for one person, but Dr. Orkin dismisses those concerns. “Of course, I don’t do it all alone. I’m surrounded by people who believe in me and what I do, and who want to be part of this. At the end of the day, we all see our work not as a job, but as a mission, and we all work together. When I interview people to work in the OR, I tell them that it’s only for people who have a passion for this work. It has to come from them in order to succeed.”

Dr, Orkin’s project manager, Shuli Egozi, says that much of her success stems from her personal example. “The staff sees her self-sacrifice for the patients and it creates a certain atmosphere that the others emulate.”

Fit to Print

While the technology for successful 3D printing already exists, Dr. Orkin says it will still take time for it to be mainstreamed due, first of all, to the high cost of individualized printing, but no less important, the need for quality control. “My hope for the future is for a company like Johnson & Johnson [the manufacturers of titanium hip replacements] to start producing their own regulated, 3D-printed prosthetic implants.”

We’re not yet at the point where internal organs can be printed out of tissue cells (although that, too, is in the process of development), but Dr. Orkin does order sophisticated 3D-printed organ facsimiles from the Synergy 3D Med company. She has on display several anatomical, pull-apart models of hearts, printed in contrasting colors, to train and assist doctors when performing complicated procedures.

Like the yellowish rubbery model that seems larger than a standard heart. A 14-year-old girl with end-stage heart failure had been on the waiting list for a life-saving heart transplant, but her cardiologist first needed to perform an interim procedure that involved inserting cannulas to pump out the blood — tricky in the best case, but all the more difficult since the girl’s heart was so enlarged and fibrous.

Synergy 3D Med produced a replica of the girl’s heart from a flexible polymer that simulates the texture of the organ and that took a total of 60 hours to print. “Using the model, the surgical team was able to determine the correct location and precise angle for the insertion of the cannulas, thereby clearing the way for the challenging procedure — hooking up the patient to an artificial heart — so that eventually she could receive her transplant,” Dr. Orkin explains. “After spending two years in and out of the hospital, she is finally back home returning to a normal life.”

Not all 3D images need to be printed. Instead, physicians can view the image in a VR (virtual reality) program that enables them, wearing specialized goggles, to manipulate it on screen. In addition to VR there is also AR (augmented reality) —computerized images with varying degrees of “transparency” enabling the physician to “see” inside the various anatomical layers.

Of course, there will always be instances where only tangible, hands-on reality will do. “One of my dreams for this technology is to help surgeons prepare for surgery by printing replicas that simulate not only the structure of the bone but also its density,” she says, familiar with the areas of potential hazard and explaining the tremendous benefit of an orthopedist having the opportunity to practice inserting a screw in a printed bone facsimile that has the precise texture as the patient’s bone, and thus being able to determine the amount of pressure needed.

As 3D-printed bone and organ replicas are revolutionizing medical care, helping physicians better prepare for surgeries, leading to drastically reduced time in the OR while improving patient outcomes, and given the astounding potential of this technology, it’s no wonder Dr. Orkin has unbridled dreams for the future — she believes the best is yet to come.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 831)

Oops! We could not locate your form.