The Lost Legacy of the Leshem

| July 1, 2025The Chofetz Chaim: “While we sit below and try to be mesaken olamos Above, the Leshem sits Above and does the tikkunim there”

Title: The Lost Legacy of the Leshem

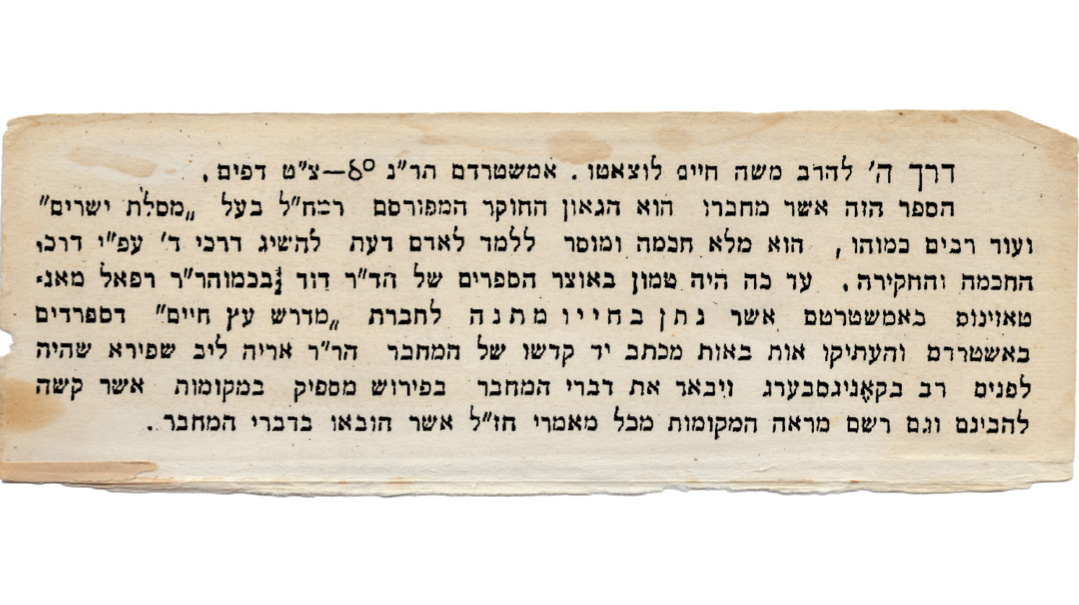

Location: Amsterdam

Document: Advertisement in HaMelitz

Time: 1896

This column is dedicated in honor of the bar mitzvah of Ari Moskowitz.

“Erev Shabbos Kodesh parshas Emor 1922, Homel,

In honor of the great rabbi and gaon, glory of the generation, my dear friend, Moreinu Harav Avraham Yitzchak Hakohein Kook, the chief rabbi shlita, his light should shine forever. I received your beloved message… that if it is my wish to travel to Yerushalayim, then you are prepared to send me an entry certificate… I wish to express my deepest thanks and blessings for arranging this. I wish to add, however, that with me in Homel is my son-in-law Harav Hagaon Rav Avraham shlita… It is very difficult for me to part from him. Therefore, I am requesting to please send an entry certificate for him as well. He is 50 years old…. My daughter Chaya Musha is 48, and they have an only child whose name is Yosef Shalom. I am requesting your assistance in arranging their immigration certificates as well. But I am not chas v’shalom asking for any financial assistance whatsoever, only entry certificates... I am currently suffering from a terrible eye ailment, may Hashem have mercy on me. That is the reason this letter is written with such brevity... Your dear friend who blesses you that you should be blessed from the Source of all blessing, with heart and soul,

Shlomo ben Rav Chaim Chaikel Elyashiv”

Having lived his long and fruitful life quietly and modestly in the Zhamut region of Lithuania, Rav Shlomo Elyashiv (1841–1926) yearned to spend his last years in the Holy City of Yerushalayim. In his youth, he had studied in Minsk under Rav Gershon Tanchum. As a young married scholar, he resided in Telz, where he became a close student of Rav Yosef Raizen, who opened his eyes to the world of Kabbalah. The young Rav Shlomo Elyashiv quickly emerged as the leading kabbalist in the Lithuanian world, and one of the most renowned kabbalists in recent centuries. As an expert in the kabbalistic approach of the Vilna Gaon, Rav Shlomo delved into the secrets of Jewish mysticism, taught a generation of kabbalists, and authored some of the most important works in this realm in the form of his magnum opus Leshem Shvo Ve’achlamah.

Upon the publication of this monumental work, the Chofetz Chaim commented, “While we sit below and try to be mesaken olamos [mend the worlds] Above, the Leshem sits Above and does the tikkunim there.” The Leshem resided in the city of Shavel for most of his adult life. According to a few different sources, Rav Yisrael Salanter either arranged to meet with his much younger counterpart the Leshem, or perhaps they had a chance encounter. Rav Yisrael Salanter, founder of the mussar movement, was completely focused on the more earthly and practical elements of human behavioral improvement. As such, he looked askance at Rav Shlomo’s preoccupation with kabbalistic studies. Despite these differences, they had great mutual respect for one another, each appreciating the holiness and contributions of their counterpart.

For years, it was believed that the funding for the publication of Leshem Shvo Ve’achlamah came from the great patron of Torah and mussar from Berlin, Ovadiah (Emil) Lachman. Supporting many Torah ventures, including the yeshivos in Slabodka, Kelm, and Telz, as well as the renowned Kovno Kollel, at some point the Berlin philanthropist was introduced to Rav Shlomo Elyashiv. Rav Nosson Kamenetsky writes:

“The introduction to the volume Sefer Hadei’ah of the weighty Kabbalah set Leshem Shvo Ve’achlamah… states, ‘A remembrance of thanks… to the gvir… who has also extended his blessing to me by being among those who support me in the great expense of publishing this sefer… His desire and wish is not to set his name in print explicitly….’ This author believes that the interpretation of the saintly Rav Elyashiv’s words explaining why he named his opus Leshem Shvo Ve’achlamah, to wit, ‘ki shmi bekirbo’… is that in the words Leshem Shvo one finds the consonants of the author’s name, Rav Shlomo Elyashiv, and in the word ‘achlamah’ one finds most of the letters of the sponsor’s name, Ovadiah (Emil) Lachman.”

However, newer research clarifies this point. While Lachman was indeed a key patron of the Leshem — providing 450 rubles for the wedding of each of his children — the benefactor for the actual printing of the Leshem Shvo Ve’achlamah itself was the philanthropist Bentzion Nurick of Shavel. The Leshem cryptically alludes to this support in his introduction, and Rav Aryeh Levin later confirmed that Nurick (then living in Riga) not only funded the printing, but also had previously helped rescue the Leshem’s manuscripts. He had sent a team of professionals to Shavel after World War I to help locate the kesavim, which the Leshem had buried underground before fleeing the invading German army.

While Lachman and the Leshem may not have partnered on the publication of Leshem Shvo Ve’achlamah, Rabbi Abba Zvi Naiman’s research has shown that they did, in fact, collaborate on another seminal project — one that may have been lost to us if not for their partnership: the first printing of the Ramchal’s foundational masterwork of Jewish thought, Derech Hashem. In a remarkable letter dated Rosh Chodesh Adar 5658 (1898), Rav Shlomo Elyashiv explicitly wrote that “almost all the works of the Ramchal until that time were brought to print through my efforts and because of me.” Chief among those was the 1896 Amsterdam edition of Derech Hashem, which until then had existed only in manuscript form.

This remarkable act of preservation becomes even more significant when one considers who the Ramchal was — and why many of his writings remained unpublished for so long. Rav Moshe Chaim Luzzatto (1707–1746) was one of the most brilliant and controversial figures in early modern Jewish history. A precocious mystic, poet, and thinker, the Ramchal began receiving what he described as maggidic revelations at the age of twenty in Padua. These claims — along with his messianic allusions and secretive circle of disciples — set off alarm bells among rabbinic authorities, who were still reeling from the trauma of Shabsai Tzvi and his false messianism just decades earlier.

Fearing another outbreak of mystical upheaval, a coalition of rabbis demanded that the Ramchal cease all kabbalistic writings and study, threatening him with excommunication. Under pressure, he agreed — at least formally — and many of his early works were hidden or destroyed. Though he later relocated to Amsterdam and produced classics such as Mesillas Yesharim and Daas Tevunos, some of his more esoteric writings remained in manuscript, including Derech Hashem. This masterful work circulated quietly among a few disciples, but was never published during his lifetime. It would take nearly a century and a half for Derech Hashem to finally reach the broader Torah world.

The catalyst for this was the Leshem, who, along with the other gedolei hador, felt an urgent need to disseminate the foundational works of the Gra and the Ramchal to fortify the generation against the winds of Haskalah. The mission required a team: a visionary, a publisher, and a financier. The visionary was the Leshem. The publisher was the Warsaw-based Rav Shmuel Luria, nephew of Rav Dovid Luria — known as the Radal. And the financier was Ovadiah Lachman, the mysterious Berlin industrialist who, after being drawn close to Torah by Rav Yisrael Salanter, became the financial backbone of the mussar movement. One can speculate that it was likely Rav Yisrael Salanter himself, anxious to see the Gra’s works in print, who connected the Leshem with Lachman, thereby forging the alliance that would change the landscape of the Jewish library.

This partnership swung into action. Rav Shmuel Luria began publishing a series of the Ramchal’s works in Warsaw, and in the introduction to Adir BaMarom (1886), he offers a “double and triple blessing” to the Baal HaLeshem, stating that it was through him that the printing was made possible. The funding, he notes, came from an anonymous donor in memory of his parents, “Zvi ben Avraham” and “Freida bas Reb Binyamin” — the Hebrew names of Ovadiah Lachman’s parents. The connection was clear.

The final piece of the puzzle fell into place in Amsterdam. A Russian talmid chacham named Rav Aryeh Leib Shapira — who had once replaced the Malbim as the Rav in Koenigsburg — discovered the pristine, 150-year-old manuscript of Derech Hashem in the Etz Haim library, which had been enriched by the collection of David Montezinos. But as he wrote in his introduction, a familiar obstacle stood in his way: “I did not have the money to print the sefer.” It was ultimately Lachman’s generosity, almost certainly catalyzed by the Leshem’s encouragement, that enabled the first edition to come to light. And while the cryptic word achlamah in the title of the Leshem’s own sefer may not have encoded Lachman’s name, the true testimony to their partnership lies in the enduring impact of Derech Hashem. Without their collaboration, this cornerstone of Jewish thought might have remained hidden in manuscript — a voice of clarity, purpose, and Divine wisdom lost to the ages.

As for the plea in that humble, handwritten letter to Rav Kook — it was answered, and in 1924, the Leshem’s final ascent was complete. His arrival in Yerushalayim was a cause for great celebration among the sages of the Old Yishuv, who eagerly welcomed the generation’s preeminent master of the hidden Torah. But a poignant new chapter had begun, one foreshadowed by the letter’s closing lines about his “terrible eye ailment.” With his eyesight failing, the Leshem, who had spent a lifetime deciphering ancient texts and composing his own monumental works, now relied on his young grandson, Yosef Shalom, to be his eyes and his hands. The very same Yosef Shalom mentioned in the letter as an “only child” — now a brilliant teenager — became his grandfather’s scribe. He would read to him, write his Torah annotations, and pen his correspondence with other Torah leaders. It was a remarkable closing of a circle: The holy sage who had orchestrated the printing of manuscripts hidden for centuries now had his own final thoughts and legacy transmitted through the hands of the boy who would become the posek hador. The Leshem passed away just two years later and is buried on Har Hazeisim, leaving his holy writings — and his holy grandson — as an eternal inheritance for Klal Yisrael.

A Family Legacy

Subsequent publication of the Leshem’s many kabbalistic works was taken care of by his son-in-law Rav Avraham Elyashiv, his grandson Rav Yosef Shalom Elyashiv, and Rav Aryeh Levin, the renowned Tzaddik of Yerushalayim, who was a mechutan, as he was Rav Yosef Shalom’s father-in-law. Rav Aryeh Levin noted in the introduction to the Leshem that when the first volume of Leshem Shvo Ve’achlamah was published in 1908, it was received in faraway Baghdad by Rav Yosef Chaim, the Ben Ish Chai. In honor of the occasion, the Ben Ish Chai recited a shehecheyanu, and instructed his children to do the same!

Carrying His Light

During the Leshem’s final years, Rav Aryeh Levin, the Tzaddik of Yerushalayim, would make a nightly pilgrimage to his side, undeterred by wind or rain. His young son, Rav Chaim Yaakov, once waited for hours in the corridor while his father was inside. On their way home, the boy’s curiosity got the better of him. “Tatte,” he asked, “what did you learn?”

Rav Aryeh’s reply was a lesson in humility for the ages. “The holy gaon,” he answered, “learned and delved into his holy seforim, and I stood next to him. I held the lamp in my hand, I handed him the seforim that he needed… and I do not know why I have the privilege of serving this holy man.”

In that profound statement lay the essence of shimush talmidei chachamim. Rav Aryeh did not see himself as a student coming to receive, but as a servant privileged to facilitate a holy fire. His role was not to learn, but to serve — to hold the lamp, to pass the seforim, to be a silent partner in the Leshem’s ascent into the highest realms of Torah.

A Sefer for All Seasons

The Leshem’s great-grandson, Rav Moshe Elyashiv shlita, related that although the Chazon Ish was known primarily as a halachic posek, he evidently was proficient in the realm of Kabbalah as well. The Chazon Ish’s custom was to only clean seforim for Pesach which he would need to use over the course of the holiday. On more than one occasion, one of the seforim that the Chazon Ish cleaned for Pesach was the Leshem Shvo Ve’achlamah. Apparently, the Chazon Ish couldn’t manage even one week without this precious sefer.

For more, see Rabbi Abba Tzvi Naiman’s groundbreaking article “The First Printing of Sefer Derech Hashem” (Lemaan Tesapeir, Pesach 2023).

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1068)

Oops! We could not locate your form.