The Light Still Shines

Rav Shneur Kotler’s pioneering vision still guides Chicago roshei kollel Rabbi Moshe Francis and Rabbi Dovid Zucker

Photos: Avi Berkman, Alex Polissky, Mishpacha archives

IF one has two grandfathers named “Meir,” he can name his son “Shneur” in memory of both, writes the Beis Shmuel in Hilchos Gittin. The name “Meir” (the root of which is “ohr”) means “bearer of light,” or “one who is bright or shines.” The name “Shneur” is “Shnei Ohr — Two Lights.”

For 19 years, Rav Shneur Kotler ztz”l served as rosh yeshivah of Lakewood’s Beis Medrash Govoha. There he learned, taught, guided, and encouraged, and succeeded in ushering in an era in which years of kollel learning became a prevalent norm. During his relatively short lifetime, Rav Shneur Kotler spread so much light.

But the spiritual glow he cast over the city of Lakewood, was just one of the lights that Rav Shneur Kotler ignited. Under his leadership, together with Rav Nosson Wachtfogel, he oversaw a movement to spread Torah across America and beyond, marshaling his troops for a mission to take the mesorah and energy of Lakewood, the steadfast commitment to limud haTorah, and share it with Yidden on the outside. Thus began the concept of community kollelim, the second “ohr” of Rav Shneur’s “two lights.”

Last week, on the third day of Tammuz, was Rav Shneur’s 40th yahrtzeit. It was on Shabbos, which Klal Yisrael welcomes with lighting at least two candles — bringing that much more ohr to the world. Rav Shneur was just 64 when he passed away, having run Lakewood’s BMG for the exact number of days as his father, Rav Aharon Kotler ztz”l, who passed away in 1962 — 19 years, seven months and one day. The Gemara in Avodah Zarah tells us that it takes 40 years to grasp the lessons of a rebbi. Rav Shneur’s lessons were many, his timeless impact spanning so many areas. One of them is the phenomenon of community kollelim now spread across the US and further afield, which has transformed the landscape of Jewish America.

It’s always a curious thing to examine the pattern of which cities succeeded in carving out an oasis within American culture, where Torah is its singular heartbeat. Today there are many, and each has its own story to tell. Although Chicago has had a vibrant Torah community for a century, it was one of the first to initiate this trend over four decades ago (Toronto was the first), and its number of mekomos haTorah is constantly growing. Of course, many people and numerous factors can be credited for this accomplishment, and the Chicago Community Kollel’s 40 years of uninterrupted limud HaTorah — a harbor in the ever-Windy City — is surely somewhere at the top of the list.

But the kollel’s hatzlachah was not born in a vacuum. Its founding roshei kollel, Rabbi Moshe Francis and Rabbi Dovid Zucker, are both talmidim of Rav Shneur, and it was under the Rosh Yeshivah’s directive, that they built one of America’s oldest and most successful community kollelim. The roshei kollel, role models themselves in Torah, avodas Hashem, and baalei achrayus of the highest order, admit that the credit is not theirs for the taking. Because behind the success they’ve been blessed with, is a figure who didn’t live in Chicago and in fact, had little to do with the city at all.

Rav Shneur Kotler didn’t really have to concern himself with a city in far-flung Illinois, or with the growth of Torah in Toronto, Detroit, Los Angeles, or any other city for that matter. His hometown was Lakewood, New Jersey, where he led a yeshivah rapidly earning the title of America’s largest — this alone was ample enough responsibility. But Rav Shneur not only cared, he acted.

“He was a great baal achrayus,” Rabbi Francis reflects. “He juggled so many responsibilities. And through it all, he was forever learning, writing, and developing chiddushim. It was truly awe- inspiring to watch.”

Rabbi Zucker recalls how Rav Shneur so frequently had to spend time away from the yeshivah, raising the necessary funds to sustain it and support its swelling number of talmidim, which jumped from 180 to 1,000 (500 bochurim and 500 yungeleit) during Rav Shneur’s tenure as rosh yeshivah. “He gave up both ruchniyus and gashmiyus for the yeshivah,” says Rabbi Zucker. “In those days, there was no sophisticated board of directors, and so much of the work fell on Rav Shneur’s shoulders.”

That sense of achrayus extended well beyond the parameters of the yeshivah. Rav Shneur was involved in myriad different projects on behalf of the klal, as well as serving on the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah. Given this context, it’s easy to see how Rav Shneur would throw his weight behind an initiative that would mean saying goodbye to talmidim of his own yeshivah for the sake of building Torah in other communities.

At a 40th-year event

Time to Leave

When the Chicago community began researching the possibility of opening a kollel, the names Dovid Zucker and Moshe Francis were suggested as the right pair to take on the job. The two had a proven record of working well together, which became apparent during their time in BMG. They had been learning in the same chaburah, when one day, Rabbi Zucker approached Rabbi Francis with an idea: Chol Hamoed, he observed, is a confusing concept. Is it chol or is it moed? With so many intricate halachos defining the parameters of this halachic twilight zone, wouldn’t it be a great service to write a book in English that explains, clarifies, and provides a clear directive regarding the laws of Chol Hamoed? Rabbi Francis agreed; it was a great idea. The two worked together diligently, ultimately publishing the sefer Zichron Shlomo: Chol Hamoed. The sefer quickly became popular, and to this day it remains a leading authority on the halachos of Chol Hamoed.

The project’s objective was to teach the world that even the days outside of Shabbos and Yom Tov can be elevated and holy. Such was the foundation of their union, a dynamic that waxed prophetic. Seeing how well they worked together, Rav Shneur strongly encouraged them to take their talents west, and open a community kollel in Chicago, Illinois. There, they would permeate America’s third largest city with kedushas haTorah, demonstrating on the ground that even chol can be kodesh.

Today, that vision is readily apparent. The Chicago Community Kollel has the fortunate problem of being unable to offer a parking spot as early as six a.m. It is full to capacity at that hour, with avreichim of the kollel, community balabatim, and a special chaburah of mechanchim all learning vigorously. The chaburos, shiurim, and one-on-one learning sessions continue throughout the day and well into the night. And, much as the kollel aims to inspire the broader community, that objective doesn’t interfere with the hasmadah of the kollel’s avreichim during seder hours. Over time, the fruits of the kollel’s labor have born fruits of its own and, today, there’s hardly a mosad in Chicago that doesn’t boast at least one, if not several, kollel alumni on its staff.

When Rabbi Dovid Zucker and Rabbi Moshe Francis formally set out to leave for Chicago, it was together with a chaburah of ten avreichim. The yeshivah developed a custom that when a chaburah left to form a kollel, the yeshivah would host a seudas preidah, a farewell party, in its honor. Rav Shneur would attend and deliver a derashah, extending his brachah for the chaburah’s success.

At the seudas preidah for the Chicago-bound chaburah, Rabbi Zucker was unable to attend as he was sitting shivah for his father. But Rabbi Francis spoke on behalf of both of them and shared the following thought: “The Gemara in Pesachim tells us ‘Kol mah sheyomar l’cha baal habayis asei, chutz mitzei — a guest must heed to whatever the host says besides for Go!’ If a guest need not obey when told to leave the home.” Asked Rabbi Francis, “why are we required to leave the yeshivah upon the encouragement of the hanhalah? Per the Gemara’s directive, shouldn’t we be allowed to defy the order?” Rabbi Francis then offered an answer. “The hanhalah isn’t saying ‘tzei — leave,’ rather, they’re saying ‘Neitzei — Let’s leave together!’ The yeshivah will be there to support us every step of the way!”

Rav Shneur smiled widely at the comment — because he knew it was true. Rav Shneur, and the mesorah he represented, would accompany those who left the beloved yeshivah to spread its light and legacy.

Before they left, Rav Shneur gave them a piece of advice: “Work on making friends for the kollel,” he said. “Don’t focus on money, focus on friends.” And then he added something else. “Your greatest adversaries will become your greatest friends. Because those adversaries are passionate people — you just have to redirect their passion. It’s the pareve people you have to worry about.”

Rav Shneur’s legacy is brighter than ever; a full parking lot at 6 a.m. is a pretty good measure of a kollel’s success

Personal Time

Rav Shneur’s vision to make the priority of Torah an international enterprise, was a reflection of his own greatness, one that his talmidim were privileged to witness firsthand. Both Rabbi Zucker and Rabbi Francis learned under Rav Shneur. Rabbi Zucker for 14 years, Rabbi Francis for 10. Rav Shneur would deliver shmuessen and shiurim regularly. “He delivered shiur on the yeshivah’s masechta weekly,” says Rabbi Zucker, “but he had a special love for the limud of Kodshim and, in addition to the weekly shiur, would say shiurim to a chaburah learning Kodshim.”

Rav Shneur’s exceptionally busy schedule made it difficult for talmidim to develop a relationship with him, but one way to get to spend time with him was by serving as his personal driver.

“At the time,” Rabbi Francis says, “the yeshivah had a rule that every bochur had to drive Rav Shneur once a year.” Rabbi Francis took advantage of this privilege; he drove Rav Shneur on several occasions and, from this close-up vantage point, was able to see greatness in the simplest, quietest acts.

“I once drove Rav Shneur to Brooklyn for a parlor meeting and waited until it was over to drive him back,” Rabbi Francis remembers. “At some point, it came to Rav Shneur’s attention that his son-in-law (and current rosh yeshivah) Rav Dovid Schustal was also in Brooklyn, returning to Lakewood in a different car. Now, at the time, Rav Shneur would prepare shiur together with Rav Dovid. He was scheduled to say a shiur the following day and so it made perfect sense for him to return in the same car as Rav Dovid, where they could review the shiur together. But Rav Shneur wouldn’t hear of it. I had driven him to Brooklyn and waited for him there. He therefore insisted that he return with me.”

But it was late, and Rav Shneur really did need to prepare for the next day’s shiur, and so they arranged to stop at a gas station en route where Rav Shneur would switch cars and continue the rest of the way with Rav Dovid.

It’s a little story emblematic of something so much bigger. An individual waited for him, and that had to be acknowledged, but the public waited for a shiur and that also had to be acknowledged. And so, he did both, switching cars and, in the dead of night, after an exhausting day, worked through the sugya with Rav Dovid Schustal. Because, in the end, it was all about Torah.

Rabbi Francis remembers another incident where Rav Shneur demonstrated this same deep level of concern. “Rav Shneur would attend the annual Agudah Convention where, as a member of the Moetzes, he was one of the first tier speakers. Now, I had been in Lakewood for a few years already, and was still a bochur. Shortly before the convention, Rav Shneur approached me. ‘Why don’t you come with me to the convention?’ he said. ‘There, I can introduce you to many people, and that might help you find a shidduch.’”

Rav Shneur’s sense of responsibility was so intense that his very body was programmed to conform to it. Rabbi Zucker and Rabbi Francis were once in his office together, and it was clear that Rav Shneur was very tired. “If you don’t mind,” he said, “I’d like to take a ten-minute nap.” Of course, they consented, and, thinking it would be disrespectful to remain in the office as the Rosh Yeshivah slept, they offered to leave. But Rav Shneur assured them otherwise, and lay down on his couch. His eyes closed and, precisely ten minutes later, opened. He was awake, ready to continue the conversation.

Rabbi Francis tells of a time when he was invited for a Shabbos seudah. For some reason, he misunderstood the invitation, thinking it was meant for the following week. “On Shabbos afternoon, I was approached by a fellow talmid, who told me that Rav Shneur was concerned about me since I hadn’t shown up as expected. He then said that Rav Shneur would like me to come over on Motzaei Shabbos for Melaveh Malkah in place of the Shabbos meal. And that’s what I did.”

Great people care about small things. From Rav Shneur’s towering perspective, a talmid missing a Shabbos seudah was something that had to be accounted for.

But greatness, of course, was not a foreign concept to Rav Shneur Kotler. He was one of two children, and the only son, of one of the greatest gedolim in America’s history.

It’s hard not to be overshadowed by a father like Rav Aharon Kotler. Few could match his brilliance, his soaring accomplishments shaped history, and he was, in every sense of the term, a larger-than-life personality.

But Rav Shneur managed to carry the unique feature of being both the son of Rav Aharon Kotler, as well as a gadol in his own right. His father was Beis Medrash Govoha’s initial rosh yeshivah, but it was under Rav Shneur’s leadership that the yeshivah saw its first growth spurt, the beginning of a rapid pace of development that continues to this day. But even as Rav Shneur dedicated himself to perpetuating his father’s legacy, his personality and method of leadership formed a legacy of its own.

“Rav Shneur learned with his maternal grandfather, Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, for ten years,” says Rabbi Zucker. “In many ways, he was more similar to his grandfather than he was to his father.”

Where Rav Aharon was a burning pillar of fire, his father-in-law, Rav Isser Zalman, was known for his neimus, his very soft-spoken mannerisms. Rav Shneur shared that same quality.

And, like his father and his grandfather, Rav Shneur had an exceptionally brilliant mind. “Rav Shneur has such beautiful Torah on so many subjects,” says Rabbi Francis. “I have a son-in-law, Rabbi Asher Weiss, who lives here in Chicago. He has a special seder to learn Rav Shneur’s seforim on Kodshim, called Siach Arev. There are many seforim written on Kodshim, but he says he finds that Rav Shneur’s seforim provide a unique and brilliant approach to the complex sugyos.”

Behind the Scenes

The story of Rav Shneur simply cannot be told without acknowledging his lifelong partner in all his endeavors. Rebbetzin Rischel Kotler a”h, who passed away in 2015, was active and involved in the yeshivah’s operations, all from behind the scenes.

“The Rebbetzin was a regal person,” Rabbi Francis relates, “and she treated Rav Shneur like the gadol that he was.” Rebbetzin Krupenia, who is Rav Shneur and Rebbetzin Rischel’s daughter, was recently featured on a video shown at a Chicago Kollel event for women. She shared that her mother would always stand up for Rav Shneur when he entered the room, and she would always wait up for him, no matter how late Rav Shneur returned home — and that was often very, very late.

In 1984, two years after Rav Shneur’s petirah, Rabbi Morris Esformes rededicated the kollel’s name as Zichron Shneur, in memory of the great rosh yeshivah to whom so much of the kollel’s success was attributed. The kollel celebrated the event, and the celebration was published in its newsletter, along with many pictures, which was sent to Rebbetzin Rischel as a testimony to her husband’s continuing legacy and to her own years of selfless dedication. But she called to register a complaint. The newsletter featured several pictures, including one of Rav Shneur — but all the pictures were of the same size, with none more prominent than the other.

“Rav Shneur was an adam gadol,” said the Rebbetzin. “He should not be featured on an equal plane with anyone else.” Even the graphic design of a newsletter, she felt, should reflect premier importance of Torah and those who carry its banner high.

One for the Road

Chicago was the first to name its kollel after Rav Shneur, but was far from the last. Today, the name Zichron Shneur can be found emblazoned across shuls and kollelim worldwide. And for good reason. Rav Shneur may have been soft-spoken by nature, but the fire of Rav Aharon was there, burning beneath the surface, fueling a passion that served as the impetus for the explosive growth of his own yeshivah, and for the proliferation of Lakewood style kollelim in dozens of communities.

In the decades following Rav Shneur’s petirah, the concept of community kollelim continued to spread, and the effect it had on American Jewry is incalculable. And at home, Lakewood’s Beis Medrash Govoha, with its thousands of students, exploded with a level of success that can only be explained as miraculous. “Gedolim tzaddikim b’misassan yoser mib’chayeihem — Tzaddikim are greater in their death than in their lives,” says Rabbi Zucker. “We never know these things for sure, but it’s possible that Lakewood’s extreme success is in the zechus of Rav Shneur’s mesirus nefesh.

* * *

A rebbi in Lakewood Cheder once pointed to a pasuk that had three consecutive words, one conjugated in the past tense, one in the present tense, and one in future tense. The rebbi gave the boys an assignment: “I want you to go home and try to find another pasuk that has the same structure.” That evening, one of the boys was in Beis Medrash Govoha where he spotted Rav Shneur. “The Rosh Yeshivah must know the answer,” he thought, and posed the question to Rav Shneur. Rav Shneur thought for a moment and then responded. “Shamati omrim neilcha,” he said, quoting the pasuk in parshas Vayeishev regarding Yosef asking the man if he’d seen his brothers, and what the man heard the brothers saying.

Shamati omrim neilcha. I heard them saying, let’s go.

Rav Shneur sent many away, far away from the glowing warmth of the kol Torah that swelled from Lakewood’s beis medrash. But those who followed this direction, never felt that they left the yeshivah’s presence. Shamati omrim neilcha — we’re in this together. That was Rav Shneur’s message. Because Shneur means two lights — one for home, one for the road.

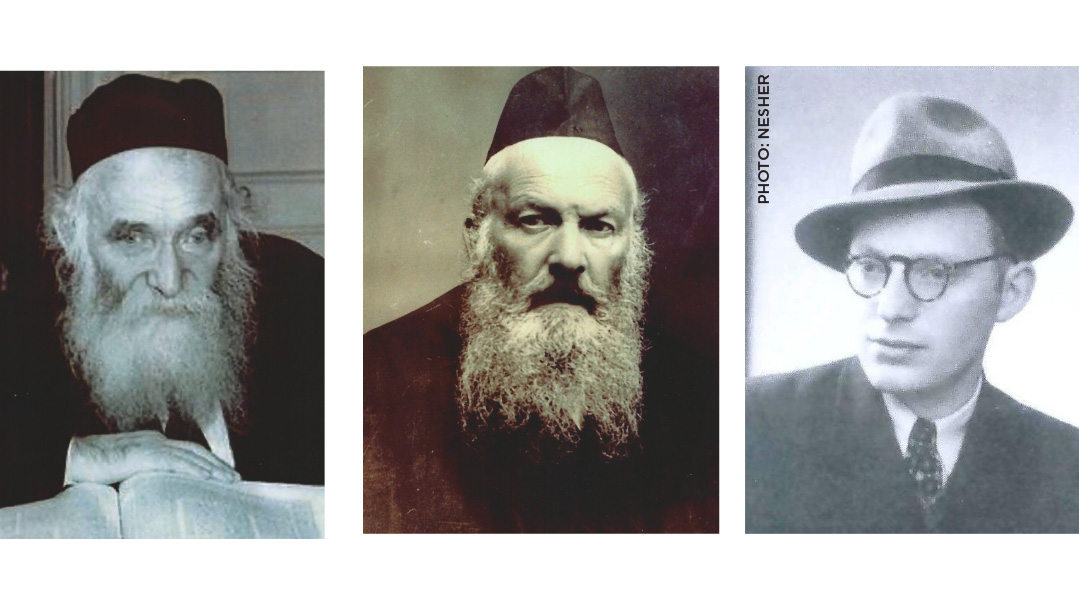

Rav Aharon (L), the shadchan Rav Elchonon Wasserman Hy”d, and the chassan, Rav Shneur. The experts told Rischel that her days were numbered, yet in the end she outlived them all

LASTING LEGACY

Rav Shneur Kotler was born in 1918 in the city of Slutzk, Russia to Rav Aharon and Rebbetzin Chana Perel Kotler, a daughter of Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer. (He was originally named Chaim Shneur, but at some point in his younger years, he fell ill and the name Yosef was added. He thus became Yosef Chaim Shneur.) As a bochur, Rav Shneur studied in Baranovich as a talmid of Rav Elchanan Wasserman, and in Kamenitz under Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz.

In 1940, shortly following the outbreak of World War II, Rav Shneur, together with his family, fled to the perceived safety of Kovno, Lithuania, along with thousands of others, among them the Friedman family of Memel, a town once part of Germany that was taken over by Lithuania. Memel had a large German-speaking populace, and this gave Hitler a pretext to annex the city, which was no longer safe for Jews.

Rav Leib (Aryeh Malkiel) Freidman, a great talmid chacham and successful businessman, who was known for his generous hospitality, realized they had to leave their native city, and in the dead of night, the family escaped to Kovno. Reb Leib was wrapped in sheets of leather and hidden in a horse-drawn wagon, while his daughter, a 17-year-old girl named Rischel, sat on the bundles of leather to help hide him. The Friedmans took up residence in the second floor of the home of Slabodka Mashgiach Rav Avrohom Grodzinski Hy”d. During these months, refugees from European cities already under German rule, flooded the streets of Kovno. The Friedman family’s trademark hospitality went into high gear, and dozens sought shelter in their home. Among them was Rav Elchonon Wasserman Hy”d, who was a close family friend of the Friedmans and stayed with them for several months — and it was he who suggested Rischel, the daughter of Reb Leib, as a suitable wife for his prized talmid, Shneur Kotler.

The two became engaged on Chanukah of 1941, an engagement that would stretch over several years. It was evident at this point that Kovno, and all of Europe, was no longer a safe haven and, the morning following their engagement, each escaped their separate ways.

Rav Shneur’s maternal grandfather, Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, was already living in Eretz Yisrael at the time and was able to secure a visa for his grandson to emigrate to Mandatory Palestine. Rischel, through a series of terrifying encounters and miraculous salvations, managed to escape to the relative safety of Shanghai, although the rest of her family was murdered in Kovno. Meanwhile, Rav Aharon Kotler and his rebbetzin managed to arrive in America, where he left no stone unturned in trying to save as many European Jews as possible, and worked tirelessly to raise funds for the refugees in Shanghai. In addition to whatever was raised, Rav Aharon would send money from his own pocket with the instruction that it be given to his future daughter-in-law.

While Rischel was in the relative safety of the Jewish community in Shanghai, she contracted a near fatal case of tuberculosis, which left her health seriously compromised. In 1946, she arrived in America and stayed with Rav Aharon and his wife, while her chassan would only arrive the following year. Still, Rischel’s health was precarious, and her medical prognosis grim. She was told she would never have children and would only live a few more years at most. Nevertheless, Rav Shneur decided to go through with the shidduch as promised, and the wedding took place in the Lakewood yeshivah building in January 1949. As it turned out, she bore nine children and outlived her husband by 33 years.

Rav Shneur and Rebbetzin Rischel settled in Lakewood. In 1962, after the passing of Rav Aharon, Rav Shneur assumed the mantle of leadership, seeing the yeshivah grow from less than 200 to a thousand. Rav Shneur led with marked kindness and humility, and the Rebbetzin, too, made a point of treating everyone with dignity and respect. There was little daylight between the yeshivah and the Kotler home, whose doors were open wide with a constant flow of talmidim and other visitors.

Rav Shneur and Rebbetzin Rischel were blessed with nine children, including five sons: Rav Meir a”h, Rav Aryeh Malkiel, Rav Isser Zalman, Rav Yitzchok Shraga, and Rav Aharon; and four daughters: Rebbetzins Sarah Yehudis Schustal, Batsheva Krupenia, Esther Reich, and Baila Hinda Ribner.

Ha’Torah machzeres al ha’achsanya shelo — Torah returns to those who graciously host it. Through their children, Rav Shneur and Rebbetzin Rischel’s legendary Torah and chesed continue, ensuring their life’s work remain a lasting legacy.

Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky joined forces with Rabbi Zucker and Rabbi Francis. “This is going to be like the Kovno Kollel”

ON A SLANT

In addition to Rav Shneur Kotler’s vision, another key figure in the founding of the Chicago Kollel, was Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky ztz”l, who was Rabbi Zucker’s rosh yeshivah in Torah Vodaath. (Rabbi Francis was also a Torah Vodaath talmid, but by the time he was there, Rav Gedalia Schorr was rosh yeshivah.) But that wasn’t Rav Yaakov’s only connection with the Chicago Kollel. When the idea of forming a kollel in Chicago was still in its nascency, a delegation of the kollel’s initial funders flew in to New York to invite Rav Yaakov to join them in Chicago for the founding meeting.

Rav Yaakov’s wife was not home at the time, and Rav Yaakov, in his classic humility, said he couldn’t commit to traveling abroad without first consulting with his wife. The group waited for the Rebbetzin to return home and, once she gave her blessing, Rav Yaakov agreed to travel. Throngs of community members, led by the community’s most prominent rabbanim, came to the airport to greet him. A microphone was brought out and, while still at the terminal, Rav Yaakov addressed the crowd. Rav Yaakov spent his first evening in Chicago, meeting with the founding donors, and the following evening, an event open for the entire community was held in a large auditorium and Rav Yaakov shared divrei brachah.

“I see the potential of the Chicago Kollel as being one that would resemble the Kovno Kollel,” said Rav Yaakov, although many in the audience raised a skeptical eyebrow. The Kovno Kollel boasted some of Europe’s finest pre-war talmidei chachamim. The Chicago Kollel would be a wonderful kollel no doubt, but could it compare to the Torah grandeur of yesteryear?

“Chacham adif m’navi,” says Rabbi Francis. “Our kollel, both past and present, has seen such incredible talmidei chachamim walk through its doors, well beyond what we envisioned.” But how did Rav Yaakov know? Perhaps it’s related to his famous interpretation of the word “hashpa’ah — influence.” Rav Yaakov would explain that it shares the same root as the word “shipuah,” which means “slant.” Like water trickling from a slanted roof, the ability to be mashpiah, is the ability to be great yourself and allow your greatness to trickle downward. Perhaps Rav Yaakov knew that the Chicago Kollel would see greatness, because he knew that that’s the only way to truly have a hashpa’ah. And, as Rav Yaakov himself once commented, “nothing can impact a city like a community kollel.”

As far as finances were concerned, Rav Yaakov had one piece of advice for the roshei kollel: “Zeit mekadesh shem Shamayim, un der gelt vent kummen mimeila— Work on being mekadesh shem Shamayim and the money will come by itself.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 919)

Oops! We could not locate your form.