The Jew Who Banked on Japan

| December 3, 2024Japan’s historic victory was due in no small part to the financial backing of Jacob Schiff

Title: The Jew Who Banked on Japan

Location: Empire of Japan

Document: Japan Times

Time: March 1906

The decades from 1880 to 1920 were a pivotal time in Jewish history. In the United States, the post–Civil War economic boom gave rise to a Jewish upper class who had immigrated from Germany in the mid-19th century. The 1880s saw the start of a massive influx of Eastern European Jews, primarily from the Russian Empire, which continued without abate until the US government curtailed immigration in 1924.

The wave of immigration from Eastern Europe would transform the American Jewish community. Millions of immigrants, largely bewildered and impoverished, faced new challenges in acclimating into American society, finding gainful employment, and retaining their Jewish identity and practices. Modern anti-Semitism was on the rise, both in the United States and internationally, and the plight of Jews suffering under the brutal czarist regime emerged as a central concern. At the same time, the rise of Jewish nationalism, especially in the form of the nascent Zionist movement, generated a sense of political upheaval.

The great 19th-century European Jewish philanthropists — Sir Moses Montefiore, Baron Maurice de Hirsch, Baron Horace Günzburg, and the first generation of the Rothschild banking family — would be eclipsed by an American Jewish philanthropist named Jacob Schiff (1847–1920), whose leadership on the Jewish scene in America and the world in general would be remembered as the “Schiff era.” He became the address for every major and minor issue of his day, and duly dispensed his phenomenal wealth for a host of causes.

His most famous and ambitious project was his financing of the Empire of Japan during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05. The czarist Russian Empire had been looking to expand its sphere of influence in the Far East, and to that end was seeking a warm water port in the region, as the waters around Vladivostok froze during the winter. The Empire of Japan was a rising power and was looking to expand its sphere of influence in Korea and Manchuria.

War broke out between the two with Japan’s surprise attack on Russia’s Port Arthur in Manchuria in February 1904. Czar Nicholas’s antiquated imperial navy sustained a series of defeats, and his Far East fleet faced complete collapse by the time Japan declared victory in 1905. Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War had far-reaching consequences for the balance of power in the region and for world history in the coming decades. It was the first time a non-European power had defeated a major European power in direct military conflict, marking the rise of Japan as a major power. Russia’s crippled naval capabilities would have a decisive impact during World War I. The battle also led directly to the Naval Mutiny, which developed into the ill-fated 1905 Russian Revolution.

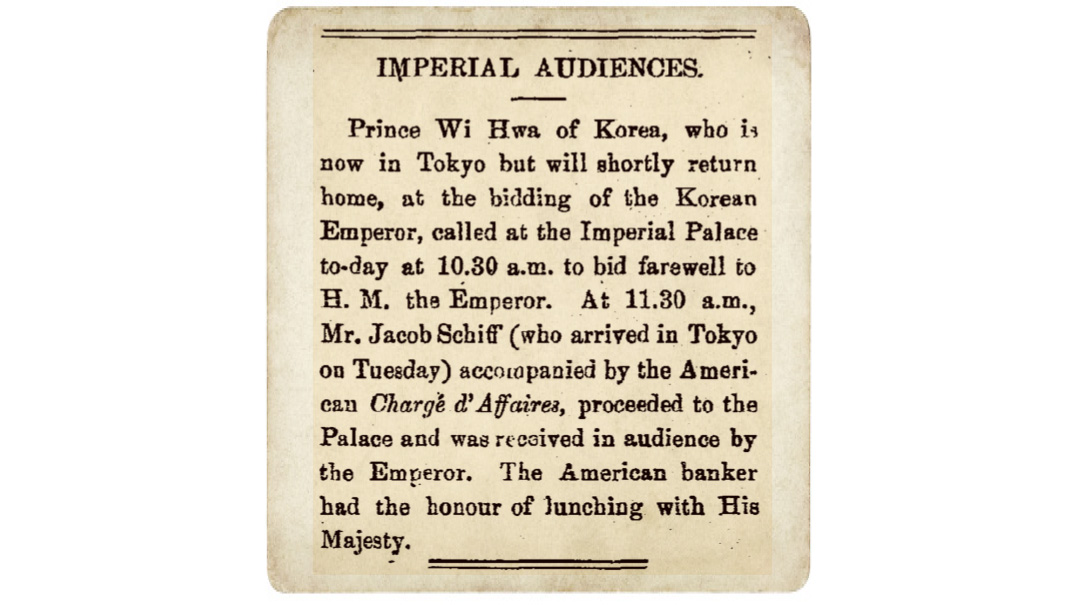

Japan’s historic victory was due in no small part to the financial backing of Jacob Schiff. In April 1904, Schiff approached Takahashi Korekiyo, vice president of the Bank of Japan, with an unexpected offer to arrange the substantial financing Japan needed to expand and modernize its navy. As the acting head of the Wall Street investment bank Kuhn, Loeb, and Company, Schiff extended a groundbreaking $200 million loan (equivalent to approximately $5.3 billion in 2024) to the Empire of Japan.

This was the first-ever Wall Street loan to Japan, and its unprecedented size — covering nearly half of Japan’s war expenses — drew international attention. While Schiff’s decision was partly rooted in financial calculations — he believed Japan’s limited gold reserves would not hinder a well-supported nationalistic war effort — he was also convinced that Japan, as the underdog, had a clear path to victory.

But the primary motivating factor in Schiff’s loan to Japan was not so much his superior business acumen but rather his sense of responsibility to the Jewish People. By the early 1900s, Jacob Schiff had been focused on the plight of Russian Jewry for more than two decades. Though he mainly assisted millions of Russian Jewish immigrants pouring onto American shores through a variety of means, he remained deeply involved with the Jews left behind under the czarist regime. He drew attention to the pogroms suffered by Jews in Russia in the 1880s, and increased his efforts after being greatly shaken by the 1903 Kishinev Pogrom. By assisting Japan against Russia, he hoped to weaken the brutal czarist regime, and perhaps even topple it through revolution, ultimately freeing the suffering Jews of Russia.

The immediate short-term beneficiaries of this wartime loan, obviously, were the Japanese, who emerged victorious in the war. Their powerful navy would dominate the Pacific high seas for decades.

In the longer term, however, the Jewish People benefited as well. They got a temporary reprieve with the failed 1905 revolution. By 1917, the Russian nation had had enough of repressive czarist rule. The February Revolution finally freed Russia and its Jews from the yoke of the anti-Semitic czar. Although the brutal Bolshevik Revolution followed in October, the collapse of the old order was mostly beneficial for Russian Jewry. In addition, nearly 40 years later there would be a fascinating butterfly effect for Polish Jewish refugees in Japan during World War II.

After the Russo-Japanese War, Emperor Meiji honored Schiff in Tokyo with the prestigious Order of the Rising Sun. Schiff’s celebration by Japan’s political, military, and business elite demonstrated the perceived power and influence of Jewish financiers in international politics. This lay the groundwork for Japan’s emerging complex attitudes toward Jews, which mixed a belief that Jewish financiers influenced global affairs with common stereotypes of Jews.

This perception led to an intriguing dichotomy in Japanese policy during the 1930s and 1940s. Some leaders developed ideas about leveraging supposed Jewish economic power to Japan’s advantage, leading to proposals like the “Fugu Plan” to attract Jewish refugees to Japanese-controlled territories in hopes of gaining access to presumed Jewish financial networks and American influence.

The memory of Schiff’s crucial support during the war with Russia would later help save thousands of Jewish lives, when Japanese diplomat Chiune Sugihara, stationed in Kaunas, Lithuania, issued over 2,000 transit visas to Jewish refugees. These refugees found temporary safety in Kobe, Japan, where the Japanese government, influenced by the positive associations with Jewish financial power dating back to Schiff’s assistance, extended what were initially ten-day transit visas into nearly yearlong stays. The refugees were treated with tolerance and respect, before ultimately being “transferred” to Shanghai in the months leading up to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Clinging to Tradition

Jacob Schiff was a descendant of the distinguished Schiff rabbinical family that traced its lineage in Frankfurt back to 1370, and he was born into that city’s Hirschian separatist community. There is a common misconception that Jacob Schiff completely abandoned Orthodoxy upon arrival in America in 1865 and joined the Reform movement, which dominated the German-Jewish “Uptown” community in New York.

However, Schiff’s dedication to the tradition of his youth was evident in numerous ways. His strict adherence to shemiras Shabbos impressed even his business associates. A notable example occurred in 1887 when he received an invitation from the president of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad for an inspection tour. Rather than simply declining, Schiff took the opportunity to explain his religious principles, writing that he would be happy to join if arrangements could be made to avoid traveling on Shabbos.

This was typical of his approach — never flaunting his observance, but never hesitating to make it known when necessary. He steadfastly refused to write letters, examine business mail, or even allow market quotations to be read to him on the Sabbath. He always walked to synagogue on Shabbos, regardless of weather or convenience.

His longtime friend and biographer, Dr. Cyrus Adler, wrote:

The depth of Schiff’s religious commitment extended well beyond Sabbath observance. Every morning, without fail, he would don his tallis and tefillin. He maintained strict kosher dietary practices and said grace after meals. His respect for synagogue sanctity was so profound that he opposed collecting funds in the synagogue even on the Day of Atonement, maintaining this position even in the face of pressing disasters that might have warranted an exception. When invited to attend an annual meeting of a Jewish philanthropic organization scheduled for a Saturday, he responded with a thoughtful critique of the practice, agreeing to attend only if he could receive assurance that no written records would be kept during the holy day.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1039)

Oops! We could not locate your form.