The Impostor in the Mirror

| March 19, 2024Feeling like a faker despite your success? How to escape impostor syndrome

With a perfect 4.0 from Brooklyn College and a terrific LSAT score, Chana knew she had a decent chance of getting into a good law school. Still, she was shocked and ecstatic when she got into a top Ivy League school. But on her first day, as she passed the daunting stone columns and stepped across the marble floor, her self-confidence gave way to self-doubt. Looking around the classroom at her peers, many of whom had graduated from Yale and Harvard, she suddenly felt like a fraud. Everyone else is so much smarter than I am, she thought. I don’t deserve to be here.

Sometimes, when people look at themselves in the mirror, instead of seeing what the rest of the world sees — an accomplished, successful person — they see an impostor, a fraud, a pretender. Despite having advanced degrees, career success, or being looked up to as a role model, they’re afraid that others will discover they’re not as talented, creative, or knowledgeable as everyone believes them to be. And they worry they won’t be able to continue to perform at their current level, since they just got there by luck or chance.

This is called impostor syndrome (IS), and don’t be surprised if it sounds familiar. It’s a phenomenon an estimated 70 percent of people will experience in their lifetime. It isn’t a mental illness, rather it’s a part of the human experience, and, like sadness or anxiety, it’s something most people are likely to feel at least once. Anyone who’s ever started a new job and thought, “Can I really do this?” has had a glimpse of impostor syndrome.

Not Good Enough

The term “impostor syndrome” was first coined by psychologists Suzanne Imes and Pauline Rose Clance in the 1970s. They surveyed 100 women, all who had been formally recognized for excellence in their fields, but who attributed their success to luck or believed that people overestimated their abilities.

Psychologists initially believed that impostor syndrome only affected professional women, but now they know that it can affect anyone, no matter their age, gender, or stage of life. Some studies suggest that women do experience impostor syndrome more frequently than men, which makes them less likely to apply for jobs they want or ask for promotions they deserve.

“We generally find that the more successful and talented people are the ones who get impostor syndrome,” says therapist Sara Eisemann, LMSW. “The people who should be the least afraid of it are the ones who get it. People who have impostor syndrome are generally measuring themselves against an impossible standard.”

Throughout law school, Chana struggled with feelings of inadequacy. As one of the few Orthodox women in her program, she felt completely out of her element. “My classmates spoke differently, thought differently, and carried themselves differently than I did. Some of them were the children of famous politicians and CEOs, and I felt like I was just little Chana from Brooklyn.”

Chana landed a prestigious job at one of the world’s top law firms after she graduated, but it only exacerbated her impostor syndrome. “I felt like I was walking a tightrope,” she recalls. “You’re with the best of the best in an incredibly intense environment, you’re terrified of making a mistake and losing your career, and then there’s this huge financial pressure to pay off your six-figure law school loans.” Her mental health suffered as a result.

When Chana would leave early on Fridays or take off for Yom Tov, she’d think, I’m a drain on resources. I’m schlepping the team down. As a result, she tried to work harder than her colleagues. She’d be the first one to offer to work late or to volunteer to work over Thanksgiving. Chana got married as a fifth-year associate, and after she started having kids, the pressure became unbearable. She couldn’t keep living this way.

For Shoshana, a computer programmer and mother of three, her impostor syndrome is primarily financial. Growing up as the second oldest in a family of nine, her parents were always worried about money. Shoshana only wore hand-me-downs and knew that extras like school trips or restaurants were out of the question. Now she earns a good income and, together with her husband, a physician, they make more than enough to comfortably support their family of five. But the habits she learned in childhood are hard to shake.

“My children ask me for money for school trips, and I say no automatically. My husband wants to eat out, and I say, ‘We’re not paying that when I can make the same thing at home for a quarter of the price.’

“I never feel like I have enough, no matter how much is in the bank,” Shoshana continues. “When my husband and I bought our beautiful house, I should’ve been thrilled. But instead, I was filled with dread. What have we done? What if we both lose our jobs and can’t pay the mortgage? I berated myself: You were too greedy. You should’ve been satisfied with renting. Whenever anything good happens to me in the world of gashmiyus, I’m always waiting for the other shoe to drop.”

Religious Impostor Syndrome

Keshet Starr is the CEO of ORA — the Organization for the Resolution of Agunot — and she says that as a baalas teshuvah she was especially prone to impostor syndrome, “In the beginning of my journey, it always felt like there was a memo that never quite made it to me.” After becoming frum, she got married and had a baby. Suddenly she was expected to pull off three-course Shabbos meals. “Everyone else made it look so easy to make Shabbos or yuntiff. Everyone else grew up knowing how to do it. I would think to myself, Why don’t I have it figured out yet? Why am I finding it so hard when no one else is?”

Trying to daven in Hebrew, surrounded by fluent Hebrew speakers, also left Keshet feeling self-conscious and out of place. And as a parent, Keshet felt like she was the only frum mom who ever found parenting challenging.

Religious impostor syndrome isn’t limited to baalei teshuvah. “I went to a shiur, and the speaker threw out a question I should’ve been able to answer from my years in a Bais Yaakov,” Shaindy remembers. “Several of my former classmates, all learned women, gave the answer immediately, and, inside, I shriveled up because I haven’t opened a sefer since my kids were born. I felt like such a phony Jew. How can I call myself frum when I haven’t learned anything for the past five years?”

Even when we have legitimate successes, we doubt ourselves and our own chashivus. “Okay, fine, I daven every day. But you have no idea how much I space out,” Shaindy continues. “And then there’s my tzniyus level — I happen to love long skirts, I prefer non-lace sheitels, and I don’t like the feel of clingy clothing. People are always telling me what a good role model I am. But they don’t know how much I struggle with technology. I’m sometimes up until 1 a.m. watching silly things on my phone. I beg Hashem for ruchniyus for my kids, so why am I not pursuing ruchniyus for myself with that same passion? And if I have such strong convictions, why do I get sidelined by stupid things?”

On the outside, Penina looks like your typical Orthodox woman. “I walk the walk, talk the talk, dress the dress,” she shares. “This is how I grew up. I don’t know anything else. But inside, I feel like my Yiddishkeit can be mechanical. I sometimes wonder if I can even call myself frum.” This, coming from a woman who is renowned in her community for her work with bikur cholim and the elderly.

One night, Penina was up late with her daughter talking about Olam Haba. “We had this amazing conversation, but I when I left the room, I felt like crying. Because who am I kidding? On any given day, I spend way more time thinking about my wrinkles and weight gain than my Olam Haba. I felt like such a fraud.”

Your Own Journey

Meira Renzoni LCSW is a therapist in Monsey, New York, who treats people with impostor syndrome. One of her clients was Leora, a brilliant tech executive who was married with three young children. Leora reached out to Renzoni because she felt like a fraud in her company and was afraid that everyone would realize she didn’t belong there. She was suffering from low self-esteem and didn’t feel that she was smart enough for her job.

“When we delved deeper, I discovered that growing up, her father had extreme anger issues,” Renzoni recalls. “He was verbally and emotionally abusive and would throw things and break dishes. Growing up, Leora learned that it wasn’t safe to be seen or heard, so she shrank herself into nonexistence.” As an adult, Leora had a hard time seeing herself as someone worthy of love and respect.

Renzoni used a modality of therapy called Internal Family Systems created by Richard Schwartz, to help Leora. Schwartz’s theory is that we all have many parts to ourselves, many of which are created when we’re children. Accepting and acknowledging those parts help us heal from childhood trauma. Renzoni helped Leora to see how the child inside of her was still afraid to be seen or heard, and in therapy, she created a safe place for Leora to express herself and work through those traumas.

A number of factors can make it more likely that someone will experience impostor syndrome. If you had parents who put an extreme emphasis on success and perfection, those messages can stay with you your whole life. Sometimes, not just parents but an entire culture can place a huge value on academic excellence, career prestige, or the image we project.

Another factor is perfectionism — you don’t feel like you’re worthy unless you’re meeting everyone’s expectations (or your own very high expectations). This mentality can seep into how we perform academically, how thin we are, how “with it” we dress, how much money we make, or how big of a tzadeikes we are.

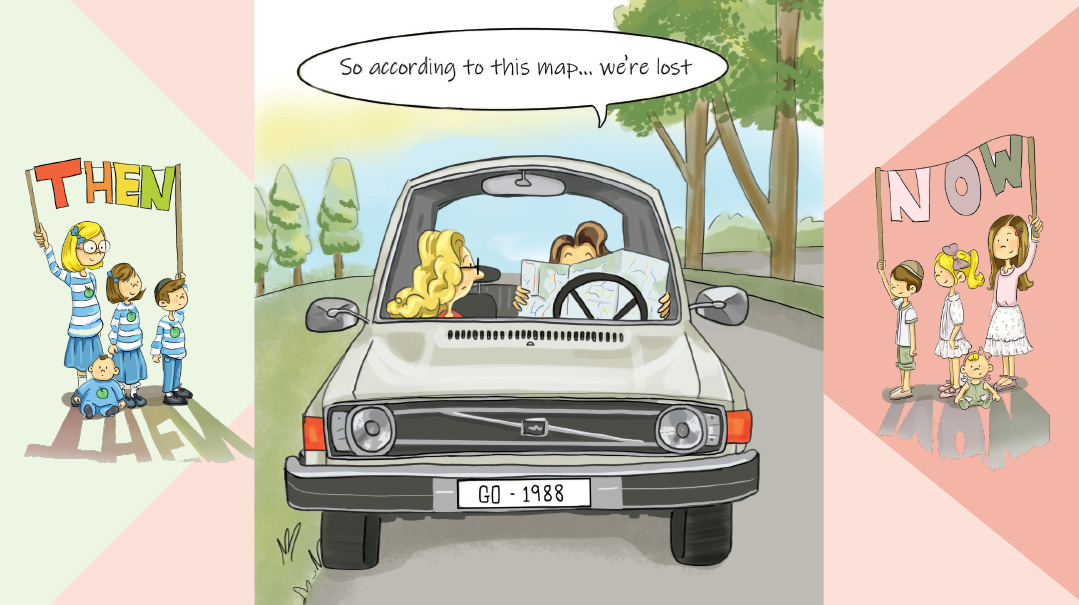

People naturally look around at their peers when they’re trying to measure themselves, and this is especially true in the frum world where we place a lot of emphasis on gedolim stories and biographies of incredible and holy Jews. The problem is, whenever we start comparing ourselves to others, we’re bound to feel less-than. If you feel good about making kugel for a new mother, but then you read about how Henny Machlis fed 100 people every Shabbos, you might feel as if your kugel is worthless.

It’s easy to fall into this mental trap, as Esti relates: “Once I saw a woman at the supermarket who was so beautifully tzniyus that I felt a twinge of envy — why couldn’t I dress that regally and look that refined? As I got closer to her, I overheard her on the phone and was appalled by the lashon hara rattling off her lips. I thought: Why do I keep making the mistake of trying to measure myself by others when everyone’s journey is so different, and we’re all tested by different things?”

So how can we overcome impostor syndrome? “It helps to do deep inner work on self-acceptance,” says Eisemann. “In a world of western values where success is measured by accomplishment, we have to bring back the value of personal worthiness in terms of tzelem Elokim. Everyone is intrinsically valuable no matter what they’ve accomplished personally or professionally.

“Remind yourself that you’re exactly where you need to be,” Eisemann adds. “When you say Modeh Ani every morning, reflect on the fact that Hashem decided the world needed you today. If you’re alive, Hashem is sending you the message that no one can do the job you can do.”

As a rabbi and Judaic Studies principal, Rabbi Simon Basalely encounters many young people struggling with impostor syndrome. “I see this especially in post-high school yeshivah students,” Rabbi Basalely notes. “They measure their success in Torah based on how well other people are learning and not based on their own potential.

“I like to tell them a devar Torah of Rav Moshe Feinstein’s: In parshas Vayeira, the order of the names Moshe and Aharon is interchangeable. Sometimes Moshe is written first, sometimes Aharon. Rashi asks the question: Why are they switched? Why isn’t the order consistent, based on age or leadership? He answers that the reversal of their names teaches us that they were equals. Later commentators are bothered by this. We know that Moshe was on a different madreigah from anyone who came before or after him. As it says, ‘G-d spoke to Moshe face to face,’ not through a dream or an angel like every other prophet did. But Rav Moshe Feinstein has a wonderful chiddush on this. He says they’re shekulim because they both maximized the potential of who they could be. In that sense, they were equal.

“There’s a chassidic story about the students of Reb Zusha, who found their master crying on his deathbed. They tried to make him feel better by telling him that he was almost as wise as Moshe and as kind as Avraham, so he was sure to be judged well in Heaven. He replied, ‘When I pass from This World and appear before the Heavenly Tribunal, they won’t ask me, ‘Zusha, why weren’t you as wise as Moshe or as kind as Avraham,’ rather, they’ll ask me, ‘Zusha, why weren’t you Zusha?’ Why didn’t I fulfill my potential, why didn’t I follow the path that could have been mine?’ I always tell my students that we serve Hashem best by focusing on our own spiritual journey and not anyone else’s.”

Rabbi Basalely believes there can be a silver lining to impostor syndrome when it sparks genuine growth in Yiddishkeit: “Just the fact that someone feels that their Judaism is a bit superficial and lacking in depth is already an amazing accomplishment. The fact that they think there could be something more is something positive.”

When students come to Rabbi Basalely complaining that their avodas Hashem is feeling rote and mechanical, he recommends they study Mesillas Yesharim, which he says is indispensable to developing a deep, introspective relationship with Hashem.

“Having a mentor is also extremely important,” Rabbi Basalely asserts. “It says in Pirkei Avos, ‘Acquire a rabbi for yourself.’ A mentor can give you a frame of reference. They can let you know the areas where you need to grow, but also make sure that you’re setting realistic goals and not comparing yourself to the bochur sitting next to you.”

For Keshet, actively nurturing positive spiritual moments helped her overcome her religious impostor syndrome. “I started giving shiurim, learning, and singing Kabbalas Shabbos. After a few years, frum life started to feel more natural, and I felt less self-conscious and out of place.”

As for Chana, after years of working as an associate, she switched gears and moved into a managerial, mentorship role at her law firm. Her new position allowed for more work-life balance and Chana no longer felt like she had to be a superwoman. Helping young associates, Chana realized that everyone she came across worried they didn’t belong there or was secretly afraid that they weren’t good enough. Everyone felt like an impostor, which meant that no one really was one.

For the first time in her career, Chana felt her impostor syndrome subside. “I became the madrichah of the law firm,” Chana says with a laugh. “First-year associates would come to me in tears because they made a mistake, and I’d say, ‘Good, you’ve made your first mistake — now that you’ve gotten that out of the way, you can move on.’ I could help the associates because I had been in their shoes.”

The Not-So-Picture-Perfect Rebbetzin

I sit in the front row of shul every Shabbos, listening to my husband’s devar Torah with a white, leather-bound siddur in my lap, my daughters sitting beside me in matching Shabbos dresses, their hair tied back with bows.

When shul is over, the ladies come up to me, and say, “Kol hakavod” with a smile and a pat on my shoulder. These ladies look up to me, they respect me. They ask me questions on hashkafah and halachah. They ask me to relay a sh’eilah to my husband for them. They don’t know that for a long time, sitting up here in the front row, I felt like the world’s biggest fraud.

After kiddush, I go home with the kids and start getting lunch on the table for my husband and the guests he’s bringing home. I sit by my husband’s side at the table as he cuts the challah. “Thank you, Rebbetzin,” our guests say as I pass the serving dish around — such a respectful, important title! For a very long time, I didn’t feel worthy of it.

In high school, I was my parents’ and teachers’ biggest nightmare. I asked too many questions, broke the dress code, went to parties, spoke back to my parents, and rolled my eyes at the teachers when they weren’t looking.

After high school, I went to a seminary for baalos teshuvah. It was one of the only places that would take me. Honestly, I wasn’t going to learn Torah. I just wanted independence and to have the Israel experience like everyone else. But it changed my life in a way I never expected. All my life I had been learning what I was supposed to do, but in seminary I learned the why. In Israel, I felt Hashem’s love wrapping around me like a blanket. I saw how He had been there for me, watching over me, through all my periods of doubt and questioning.

I stayed in Israel for two years, and when I got back, I was more observant than the rest of my family. In fact, I think that part of the reason I had acted out was the dissonance between what I was taught in school and what we were doing at home.

I was introduced to my husband when I was a sophomore in college. He was a baal teshuvah who had been studying in yeshivah for three years and planned to learn for at least a few more. He didn’t blink when I told him about my high school turmoil. “Your past isn’t important to me,” he told me. “What’s important is where you’re going.”

We got married and had a baby soon after. My husband continued to learn, with both sets of parents supporting us. Then my husband got offered a position as a rabbi in a more modern, out-of-town community. It was a good opportunity, and my husband felt ready to take it.

And that’s how I became The Rebbetzin.

In my long skirts and my sheitel, people look up to me and think I’m the picture-perfect Rebbetzin, but I still feel like me — the same crazy kid who dyed my hair blue in high school. Like everyone else, I am a work in progress, no better or worse than anyone else. I still have to work on concentrating on my davening, on controlling my temper, on guarding my tongue. For years, I felt like flinching whenever anyone called me Rebbetzin. People would come to me with hashkafic questions, and I would think to myself, “Why are you asking me? Isn’t there someone holier you can ask?”

When I spoke to my husband, he didn’t get it. “In high school I was eating treif. What are you complaining about?”

But it wasn’t the same. My husband is a baal teshuvah. Growing up, his family thought it was okay to go to McDonalds as long as you left the cheese off the burger. I had gotten a yeshivah education. I should have known better. The guilt gnawed away at me. The high esteem my community held for me left me feeling like a total fraud.

One day, I spoke to a mentor of mine from seminary about this, and her answer changed everything. She said, “You’re a better rebbetzin for having had to overcome challenges. You can be more empathetic, less judgmental, and relate to your congregants’ struggles better since you’ve made mistakes yourself. If you had been the perfect Bais Yaakov girl in high school, you might look down on the less-observant congregants. Having gone through your own struggles makes you a better rebbetzin, and maybe it’s for that reason that Hashem gave you that challenge in high school.”

Her words changed my whole outlook. I’d always thought I had failed my test as a teenager, but now I realized that I had gone through it for a reason. More years as a rebbetzin also helped me to feel more comfortable in my role.

Now, as I sit in the front row surrounded by my family, instead of feeling like a fraud, I feel proud of how far I’ve come.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 886)

Oops! We could not locate your form.