The Humblest Mountain

How child prodigy, halachic master, and light of the yeshivah world Rav Nota Greenblatt put the souls of his people first

Photos: Family archives

A young yeshivah student entered the Greyhound bus station in Memphis, Tennessee.

It was 3:30 a.m., and the eerie silence was broken only by the occasional groans of several unfortunate individuals lining the halls. The boy looked around anxiously, not finding what he was looking for. Suddenly, a bus pulled up, and its doors opened.

Only a few passengers shuffled off the bus, bleary-eyed and exhausted. The boy waited till he spied the passenger he was looking for — a tall old man resplendent in a tan suit and straw hat, striding quickly and confidently as if it were broad daylight.

“Hey, Rav!” the yeshivah student called out. The old man looked up, smiled, and waved, and the two walked toward each other. “Rav,” the boy repeated, “how was the trip?”

The old man beamed. “The trip? It was wonderful! While in Little Rock, Arkansas, I visited the library of a local shul. There, I found a sefer I’d been hoping to find for a long time. I asked the rabbi if I could have it — and he said yes! I spent the entire trip learning from the sefer. Incredible!”

The rabbi and his student left the bus station, entered the waiting car, and drove home.

The stories come fast and furious, each with their own color, their own message. But they never end emphatically, these stories; the teller’s eyes inevitably look off toward the distance, and the voice trails, “Rav Nota, Rav Nota. He was just … just....” Just what?

It’s a question that hangs unanswered and that explains the sort of desperate tone these stories are shared with. Those who bore witness all share the sentiment that the stories only scratch the surface of greatness they felt, but aren’t able to communicate. In the month since his passing, a plethora of hespedim were delivered, notes, letters, and anecdotes were shared, and slowly, the pieces are coming together. After 96 years, we begin to get a glimpse into the mountainous neshamah, no longer staunchly concealed behind a tan suit and straw hat.

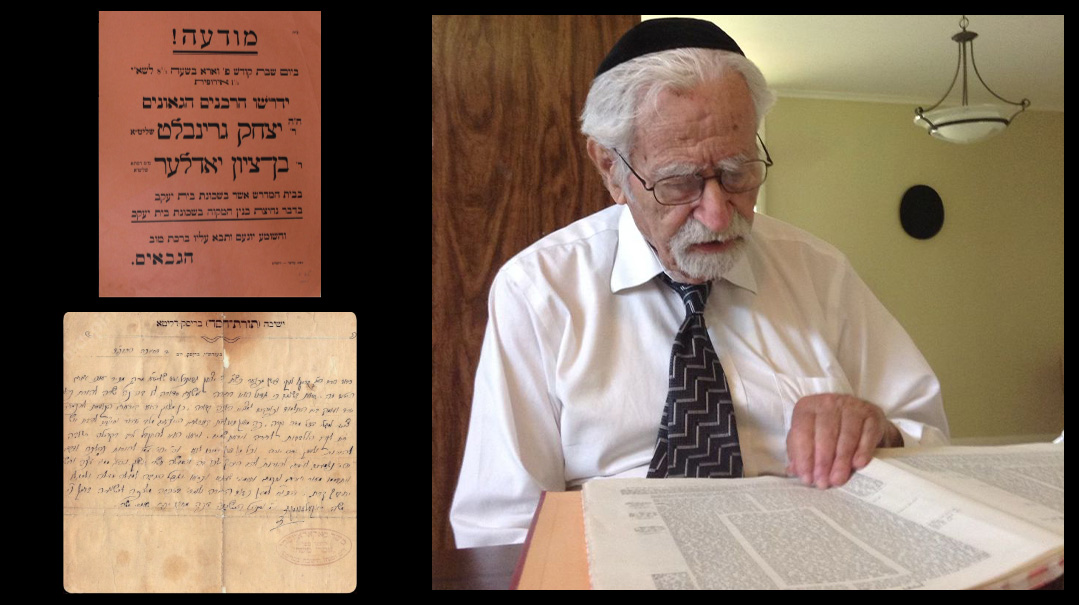

A letter of approbation from Rav Moshe Sokolovsky to Rav Yitzchak Greenblatt, and an announcement of his upcoming derashah, paved the way for Rav Nota’s father in the US. Rav Nota, blessed with arichus yamim by Rav Kook, had an example to follow

A Blessing Fulfilled

Rav Nota Greenblatt was born in Washington, D.C. on the second day of Elul, 5686 (1925), to Rav Yitzchak and Sarah Rivka Greenblatt. He was the youngest of five children. Rav Yitzchak, a native of Brisk, was extremely close with Rav Chaim Soloveitchik and was childhood friends with Rav Chaim’s son, later to become known as the Brisker Rav. Rav Yitzchak was an eloquent speaker and talented fundraiser.

In this capacity, Rav Yitzchak was sent to America to raise funds on behalf of Yeshivas Toras Chesed, Brisk’s preeminent yeshivah led by Rav Moshe Sokolovsky, better known as the Imrei Moshe. At some point during his trip, he determined that he wished to stay in America and sent for his wife and children. The Greenblatts settled in Washington, D.C., where Rav Yitzchak assumed the position of rav for the Volliner shul, a congregation primarily composed of Jews from chassidic backgrounds. It was there that Rav Nota was born, a ben zekunim, the only American-born child in his family.

Three years later, in 1928, Rav Yitzchak was offered a rabbinic position in Ellenville, New York, where he’d have the opportunity to serve as rav for the entire city, not just a shul. He accepted the offer, and the Greenblatts moved to Ellenville.

But the move was short-lived. Just three years later, Rav Yitzchak decided to respond to his heart’s calling and move to Eretz Yisrael where he could go back to learning full time. In 1931, the Greenblatts, with five-year-old Nota, headed due east.

For the rest of his life, Rav Nota would recount his experiences in Yerushalyim shel Maalah, always with much emotion. In all likelihood, it was this exposure to spiritual grandeur that shaped Rav Nota’s aspiration for greatness for decades to come.

Rav Nota would tell of his visit to the Kosel one Shabbos. At the time, the British mandatory rulers gave control of the site to the Muslim Waqf, who used part of it as a garbage dump. The stench from the garbage was so intense that young Nota passed out. He awoke to find himself in the home of a Yerushalmi family whose home was bare save for a table where they sat around singing zemiros. There was something ethereal about that singing, a majestic beauty that captured the heart of young Nota. Years later, he would say that the Yerushalmi family possessed the “osher v’chavod — wealth and honor,” we ask for in Bircas Hachodesh.

It’s an interesting contrast: The stories that characterize Rav Nota’s life are spectacular and dramatic, describing a man who logged thousands of air miles to perform outstanding feats for Klal Yisrael. But the stories that Rav Nota loved to tell were markedly plain; he reveled in the beauty of their simplicity and saw timeless lessons within them. One such story happened on Erev Yom Kippur, when he noticed a few younger men flanking a much older man on his way to the mikveh. Rav Nota was intrigued. “He’s 106 years old,” he was told. “He received a brachah for arichas yamim from Rav Akiva Eiger.” This story always excited Rav Nota. “I saw a Yid who saw Rav Akiva Eiger!” he loved to say.

At some point during his childhood, Rav Nota fell ill. His father took him to Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohein Kook ztz”l. Rav Kook was wearing his tallis and tefillin, as was his custom throughout the day, and he brought young Nota underneath his tallis and gave him a Bircas Kohein. He then davened that Nota have a refuah sheleimah and gave him a brachah to grow to be a talmid chacham and enjoy arichus yamim. Rav Nota attributed his long and generally healthy life — he never took an aspirin or visited a doctor until his final illness — to Rav Kook’s blessing. In his humility, he’d comment, “at least one brachah came true.”

Another encounter with Rav Kook took place on Leil Shavuos, when the Rav would deliver a shiur on the Rambam’s minyan hamitzvos. The shiur would begin at 11:00 p.m. and run until 4:00 a.m., with Rav Kook remaining in a standing position for five consecutive hours. Rav Nota was a young child, but he attended the shiur nonetheless, and at some point he interjected with a question. Rav Kook’s reaction was one of outright shock — he couldn’t believe that a young child could maintain such focused attentiveness and keen comprehension.

Even Rav Nota’s formal education was replete with lessons in greatness. He learned in the Chayei Olam cheder where his rebbi was Rav Chaikel Miletzky, and he also learned under the famed Russishe Melamed, father of Chevron Rosh Yeshivah Rav Aharon Cohen. Several of his classmates went on to become famed rabbinic figures, including Yerushalmi posek Rav Yisroel Yaakov Fischer and his brother, Rav Shlomo.

Where Are You Headed

If Rav Nota’s childhood years in Eretz Yisrael provided daily encounters with heightened spirituality, it was the next stage in life that allowed for hands-on interaction with it. When Rav Nota was 13, the Greenblatts returned to America. Rav Yitzchak took up the position of rav in Newark, where he founded a day school that continues to operate to this day.

Rav Yitzchak also needed to choose a yeshivah for Nota. During his fundraising years, he’d developed a relationship with Mr. Yaakov Yosef Herman, subject of the famed biography All For The Boss. Rav Yitzchak also got to know Mr. Herman’s son-in-law, a young man by the name of Chaim Pinchas Scheinberg. He’d been deeply impressed with this young talmid chacham, and, upon learning that he’d been hired as a maggid shiur in Yeshivas Chofetz Chaim, a fledgling new yeshivah founded by Slabodka protege Rav Dovid Leibowitz, he felt it would be a good fit for Nota.

While Nota was by far the youngest student in the yeshivah, Rav Dovid took an immediate liking to him. The esteem in which Rav Nota was held in Chofetz Chaim is evident from a journal that the talmidei yeshivah published, which features the shiurim and shmuessen of Rav Dovid. Rav Nota is listed as the compiler for much of the work. He was just 13, but the style of writing reflects the depth of someone many years older.

Rav Dovid Leibowitz was in poor health during Rav Nota’s time in the yeshivah, and Rav Nota spent many hours at the Rosh Yeshivah’s bedside. He had a lifelong thirst to learn whatever he could about gedolei Yisrael, and he seized this opportunity to pepper Rav Dovid with questions about his personal relationships with many of the leading European gedolim of that era.

The overarching theme that Rav Nota learned from Rav Dovid was that of gadlus ha’adam, the core philosophy upon which the Slabodka yeshivah was founded. Rav Dovid embodied this principle to its fullest, and Rav Nota watched and internalized as it played itself out in real time.

Rav Nota loved to tell of a fellow talmid in the yeshivah, a boy who wouldn’t learn at all. “He would come to the beis medrash with a comb and a mirror and spend his entire time there combing his hair.” In those days, not only did yeshivah students not pay tuition, they were actually given a stipend by the yeshivah. That meant that Rav Dovid had to spend money on a boy who learned nothing. But Rav Dovid never said a word to him and refused to throw him out.

Rav Nota would marvel at the story. “Rav Dovid didn’t have enough to feed himself, yet he fed this boy.” But, Rav Nota would conclude, “Dus iz Slabodka — that is Slabodka.” The boy may not learn, but his exposure to yeshivah would lend him insight into what Torah is. “Gadlus ha’adam,” Rav Nota would repeat, “gadlus ha’adam.”

Rav Nota would recount the story of the Agudas HaRabbanim convention that Rav Dovid attended in the 1920s. Fellow Slabodka alumnus Rav Yosef Konvitz addressed the crowd and made an ominous prediction. “American boys will never be bnei Torah. Der gantze maaseh is Dodgers udder Yankees! — all they care about is the Dodgers or the Yankees!”

Hearing this, Rav Dovid leaped up. “Yossel!” he cried, “Hust meshugeh gevuren — have you lost your mind? Der Americanishe bochur is mer mesugel tzu zein a ben Torah fun der Litvishe bochur — The American bochur is more fit to become a ben Torah than the Lithuanian bochur!”

“Everybody laughed at him,” Rav Nota would comment, “but he proved it. Rav Dovid proved it.”

There was a line that Rav Nota liked to repeat in the name of Rav Dovid, a message that bore uncanny significance as it pertains to Rav Nota’s life work. “If your intentions are pure,” Rav Dovid would say, “and you know where you’re headed, and you know how to talk to people — there’s nothing in the world you can’t accomplish.”

Rav Nota studied in Chofetz Chaim for a period of close to three years. There, he learned about gadlus ha’adam, to never stop believing in a fellow Jew, and, just as importantly, to never stop believing in yourself. “If your intentions are pure… and you know where you’re headed… and you know how to talk to people… there’s nothing in the world you can’t accomplish.”

Nothing could serve as better preparation for Rav Nota’s life moving forward.

Pivotal Meeting

It was sometime on or around Succos of 1941 when Rav Nota was introduced to a Mirrer talmid by the name of Michel Feinstein who had just arrived in America. Rav Nota had heard of Rav Michel — he was already well known in the yeshivah world as one of the Mirrer Yeshivah’s most outstanding students, in addition to being one of the first students of the Brisker Rav. Rav Nota was 16 years old at the time, and Rav Michel well into his thirties, but the two hit it off immediately. Rav Michel told Rav Nota that a cousin of his by the name of Rav Yoshe Ber Soloveitchik had opened a yeshivah in Boston called Heichal Rabbeinu Chaim Halevi.

Rav Michel intended to join the yeshivah after Succos where he would deliver shiurim during the week and asked Rav Nota if he’d be willing to join as well. Rav Nota accepted and soon joined Heichal Rabbeinu Chaim Halevi where he became a talmid of both Rav Yoshe Ber as well as Rav Michel. Although Rav Michel served as a maggid shiur, his relationship in learning with the 16-year-old Nota was such that, when Rav Michel set out to write and submit his first shticklach Torah in the popular HaPardes journal, he recruited 16-year-old Nota to help him.

The arrangement in the yeshivah was that Rav Michel gave shiurim during the week while Rav Yoshe Ber delivered shiurim on the weekends. Rav Nota would describe how Rav Yoshe Ber’s shiur could go on endlessly, straight through the night, and the talmidim would stop him, saying, “higia zeman Krias Shema.” The hasmadah that was experienced while in Boston was incredible. Rav Nota once recounted that there was no scheduled Shacharis there. “We learned until we collapsed. When we woke up, we davened and went back to learning.”

Rav Nota’s time in Boston was one of rapid intensity; he once commented that, in terms of learning, it was the greatest year of his life. But the yeshivah closed down, and after one year, both Rav Nota and Rav Michel headed back to New York where they joined Mesivta Tiferes Yerushalayim, under the leadership of Rav Moshe Feinstein.

You Can Answer

The time spent learning under Rav Yoshe Ber and Rav Michel had given Rav Nota a vivid insight into the withering accuracy demanded by the Brisker derech halimud. Rav Nota cherished this approach, and it ultimately defined his own method of learning. This, along with the personal relationship he would develop with the posek hador, would set the stage for what became Rav Nota’s legacy — an instant clarity in the most intricate areas of halachah.

Rav Nota was all of 17 years of age when he joined Rav Moshe’s yeshivah, but Rav Moshe took an instant liking to him. In yeshivah, he’d learn b’chavrusa with Rav Michel — whom he forever considered his primary rebbi in lomdus — but he also spent a lot of time in Rav Moshe’s home. The phone in the Feinstein home was constantly ringing, with sh’eilos pouring in at a rapidly increasing pace. Rav Moshe asked Rav Nota to manage the myriad calls but this responsibility wasn’t solely administrative. “You can answer the questions yourself,” Rav Moshe told his 17-year-old talmid. “If you don’t know the answer, then come to me.”

It was Rav Nota’s first foray into the world of psak, emboldened by the vote of confidence and clear directive of America’s greatest posek. But the chinuch that Rav Moshe imparted wasn’t merely academic. Rav Moshe was the quintessential oheiv Yisroel and placed central importance on tending to the needs of others, particularly the lonely. Rav Moshe instructed Rav Nota to visit an elderly European Rav, known as the Viski Illui, who would spend his days learning alone, in East Side’s Moshav Zekeinim Beis Medrash. As per Rav Moshe’s direction, Rav Nota asked him to learn b’chavrusa with him, and the two learned Menachos together.

On another occasion, Rav Moshe and Rav Nota took the train to visit the second wife of the Chofetz Chaim, who was in a hospital in New York. When they entered her room, they saw she was crying.

“Why are you crying?” Rav Moshe asked.

“Twenty years ago, I was unwell,” the woman explained. “I was worried but my husband, the Chofetz Chaim, told me, ‘zurg nisht, ihr veht lebehn nuch tzvuntzig yuhr — don’t worry, you’ll live for another 20 years.’It’s been 20 years since I received that brachah,” she concluded, “and that’s why I’m crying.” She passed away later that year.

During the years Rav Nota spent alongside Rav Moshe, reports of the destruction of European Jewry reached America, and Rav Nota would describe how when Rav Moshe would daven, he would “cry like a baby.”

Rav Nota wasn’t merely an observer of Rav Moshe’s sensitivity; he was a recipient as well. Rav Nota recounted how he went to visit Rav Moshe one summer in the Catskill mountains. He arrived in the evening, and Rav Moshe greeted him warmly. As they spoke, Rav Moshe noticed that Rav Nota had a cough. Rav Moshe insisted that he stay the night rather than travel back to New York.

“I didn’t sleep that night,” Rav Nota said. “You know why? Because Rav Moshe didn’t sleep. He came into my room every half an hour to make sure the blanket was covering me properly.”

Aside from the war years, Rav Nota said, he never saw Rav Moshe cry. Except once. A fellow living in Mississippi asked Rav Nota a sh’eilah. “We have a minyan on Shabbos,” the questioner explained. “I go to shul, and my son manages the store. But I’m wondering, would it be better if my son goes to shul, and I manage the store?”

Rav Nota paskened that indeed, that would be the better option. He then relayed the sh’eilah to Rav Moshe. Rav Moshe became visibly emotional and said “ich halt beim veinen — I’m about to cry.”

Rav Moshe’s example left an indelible impression on Rav Nota. The ability to know so much and to care so deeply was Rav Moshe Feinstein’s legacy and Rav Nota Greenblatt’s inspiration.

Rav Nota studied under Rav Moshe for four years before deciding it was time for him to return to Eretz Yisrael. Just a few months prior, Rav Michel had made the move, traveling to Eretz Yisrael by plane. Now, Rav Nota heard the calling as well. Rav Moshe gave him a farewell gift, a letter of approbation that expressed his appreciation for this 21-year-old yeshivah student, part of which reads in translation:

This is a letter about my beloved friend who learned by me for several years. He is a gadol b’Torah, in Gemara, Rashi, Tosafos, Rishonim, and Acharonim, and many, many areas of Torah, with a clear and proper understanding and he is destined for greatness …. And I am confident that in a short period of time, he will grow in Torah and yirah to become one of the gedolei Torah V’Yisrael and a pillar of halachic ruling in the world.

This letter remained hidden away in Rav Nota’s files, never revealed until his children discovered it a few weeks before his passing.

Armed with the lomdus of Brisk, the mussar of Slabodka, and the hands-on halachic training by Rav Moshe, Rav Nota headed off to Eretz Yisrael.

Going Home

It was 1946, the world was beginning to recover in the aftermath of World War II, and international transportation was slowly resuming. Rav Nota took the first ship — an American military ship — that traveled from America to Eretz Yisrael. At the time, an American-born yeshivah bochur traveling to Eretz Yisrael to learn was still very much an anomaly — so much so that people would point to him and say “that’s an American.”

Rav Nota arrived in Yerushalayim on Erev Pesach, and on Chol Hamoed, he went with Rav Michel to visit the Brisker Rav. The Rav was friends with Rav Nota’s father from their childhood in Brisk, and he welcomed him warmly. Rav Nota would often daven with the Brisker Rav, and, although at the time, the Rav gave shiurim infrequently due to health issues, whenever he did deliver a shiur, Rav Nota would make an effort to attend.

During his time in Eretz Yisrael, Rav Nota didn’t enroll in any formal yeshivah. Instead, in the morning he studied at the famed Machon Harry Fischel (founded in 1931 by philanthropist Harry Fischel) and in the afternoon he studied in the Otzar HaSeforim of the Chevron Yeshivah, where he became known as “the illui of the Otzar.” He learned b’chavrusa with the Chevron Rosh Yeshivah, Rav Aharon Cohen, and together, they learned the entire seder Nashim and seder Nezikin.

Rav Nota’s deep yearning to connect with gedolei Yisrael went into high gear during these years, and he developed close relationships with Reb Leib Shachor, with whom he learned b’chavrusa, the Chazon Ish, Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, and the Imrei Emes of Gur. Rav Nota even took walks with the Imrei Emes, whose beis medrash was near his apartment, and he would later describe the elder Rebbe as an extremely down-to-earth person with whom he enjoyed many pleasant conversations.

A short while after his arrival, another bochur came from America to Eretz Yisrael, a young man by the name of Yitzchok Scheiner. Being American born and bred, young Rav Yitzchok Scheiner’s first language was English, with neither Hebrew or Yiddish being a close second. Rav Nota, who spoke all three languages fluently, took him under his wing. Ultimately he suggested a shidduch idea for Rav Yitzchok: the daughter of Rav Moshe Bernstein, granddaughter of Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz. The two married, and Rav Yitzchok ultimately succeeded his father-in-law as the rosh yeshivah of the Kaminetz Yeshivah in Eretz Yisrael.

Rav Nota himself wouldn’t consider marrying into an Israeli family. He once explained this philosophy. “They didn’t need me in Eretz Yisrael,” he said. “In America, they needed me.”

Rav Nota indeed returned to America, though under unfortunate circumstances. In the year 1948, Rav Yitzchak Greenblatt left Newark to retire in Eretz Yisrael, even purchasing a home in Yerushalyim. But, shortly thereafter, he was diagnosed with cancer and was forced to return to America for medical care. Rav Nota joined him on his trip back.

A New Frontier

Now in America, Rav Nota set out to make the difference he envisioned. An ad in the newspaper caught his eye. Kehal Anshe Sefard of Memphis, Tennessee, was looking to fill the position of chazzan and teacher in its Talmud Torah. Rav Nota was interested, and his friend from Yeshivas Chofetz Chaim, Rav Binyomin Kamenetzky, drove him to the train station. Rav Nota Greenblatt was off to Memphis.

There were only a few shomer Shabbos families in Memphis at the time, and those who wished to give their children a Jewish education sent them to a Talmud Torah based out of the shul. But Rav Nota wanted more. Although he himself taught at the Talmud Torah, he was determined to establish a fully operational Hebrew day school.

Together with his lifelong friend, Reb Yehoshua Kutner, the two went from door to door, pleading with parents to send their children. They would search through the phonebook, looking for Jewish-sounding names, and pay unannounced visits at the addresses they found.

Rav Nota’s sincerity and endearing way of connecting with people paid off. After a whirlwind of herculean effort, the school opened in September of 1949 — within the year of Rav Nota’s arrival. There were 19 children in the kindergarten and another 19 in first grade. Rav Nota himself was one of the teachers, teaching alef-beis, about Shabbos and kosher, and all the other basics of Yiddishkeit to children whom for the most part never would have known this. He took no salary for his job at the day school and lived off whatever he received from the shul.

After two years of teaching at the school, Rav Nota moved to the background, taking on a more advisory role. Today, the day school’s alumni counts in the hundreds, many who entered completely secular and graduated to go on to the most prestigious yeshivos and seminaries. In many cases, the religious transformation of a student had an effect on his or her whole family. Rav Nota counted the Memphis Hebrew Academy, later to become the Margolin Hebrew Day School, as one of his greatest accomplishments; it remained near and dear to him until his final day. He once expressed that he stayed in Memphis for this reason, to be there for the school, to oversee its progress, and to ensure its continued success.

With lifelong friend Reb Yehoshua Kutner

Match Made in Heaven

Living in Memphis at the time was a young woman by the name of Miriam Kaplan. Her father was a simple laborer who got fired each week because he refused to work on Shabbos. Her grandfather owned a dry goods store in downtown Memphis and used to ask his granddaughter to check for the three stars after Shabbos before opening his store for the week, refusing to trust his own judgment as it might be tainted by financial incentive.

For Miriam as well, shemiras Shabbos came with its fair share of sacrifice. There were no Bnos gatherings in those days; keeping Shabbos meant staying home all day. And that, in turn, meant not going to the Friday night social events which, in Memphis of those days, were how shidduchim were made.

It was a sacrifice soon to be richly rewarded. When a young Orthodox bachelor by the name of Nota Greenblatt came to town, it seemed like the natural fit. The shidduch was redt, and the two were soon married. Together, they had five children, three boys and two girls. Their home had a tangible warmth to it, fun, loving, and upbeat. Rav Nota and Rebbetzin Miriam seldom disciplined; their chinuch was by way of living example. The children learned to value each moment, not because Rav Nota instructed them to do so, but simply because, whenever the conversation turned to something idle or unconstructive, Rav Nota would wordlessly get up, walk to his study, and resume learning.

Local Impact

Over time, Rav Nota would grow into an international destination for those in need of help, guidance, and direction. But all that happened later. Well before it was in vogue, Rav Nota ran a single-handed kiruv operation, it’s informal style classic of his personality. His interactions with community members resulted in numerous families becoming frum. During the shivah, there was a recurring refrain: “If not for Rav Nota, we would not be frum.” When a student of the day school expressed interest in learning more than the school offered, Rav Nota would offer his personal tutelage. When a student wished to move on to learn Eretz Yisrael, Rav Nota would be there, often succeeding in gaining the student admission into some of the most renowned yeshivos. An alumnus of Ner Israel Baltimore once recounted that had he not known better, he would have thought Memphis, Tennessee, was one of the major Jewish metropolises. “We had about 12 bochurim in the yeshivah from Memphis, each one a metzuyan,” he recalled.

But Rav Nota’s influence was wide as it was deep; it wasn’t only yeshivah bochurim he was concerned with. Rav Nota once learned of a Jewish boy engaged to be married to a non-Jewish girl the following week. Rav Nota spent the entire night with him, walking the streets of Memphis until the wee hours of the morning, when the boy finally agreed to break off the engagement.

Rav Nota would give occasional shiurim in Memphis, most notably, his Yom Tov shiur, and he’d relish in the opportunity to share from his vast treasure trove of Torah.

If in Shamayim the maps are drawn using spiritual metrics, Memphis, Tennessee, is a prominent country indeed, and Rav Nota Greenblatt is very much its Founding Father.

On the steps of the day school, going door to door and pleading with parents

Achieving the Impossible

A part of the mystique surrounding the story of Rav Nota Greenblatt is that he had little in terms of formal rabbinic positions. He served as a chazzan, a teacher, and an assistant rabbi for some time but, aside from a shul in his home that hosted a Shabbos minyan, he never held an official position as rav. Rather than pursuing honorary titles and handsome careers, he focused on gaining expertise in the areas of halachah that were both the most difficult as well as the most necessary, including subjects such as bris milah, shechitah, kashrus, gittin, chalitzah, eiruvin, and mikvaos. Rav Nota spent years, tucked away in his study in Memphis, mastering these intricate halachos. Over the years, he would build eiruvin and mikvaos in countless cities throughout the United States, and was involved in many areas of kashrus, assisting the OU and many other kashrus organizations in many of their projects. Perhaps most importantly, he sought to train other rabbanim in these fields as well so that they could rule on these issues independently. Many of today’s great rabbanim consider themselves students of Rav Nota Greenblatt. But, more important to note is that, much as Rav Nota was singularly independent, a trailblazer in so many ways, he always paid adherence to Klal Yisrael’s accepted minhagim. He was once asked about the minhag to read the haftarah of Shabbos Chazon to the tune of Eichah. “Isn’t the minhag incorrect as it is a public display of mourning on Shabbos?” the questioner asked. Rav Nota laughed. “It is better to end up in Gehinnom with the rest of Klal Yisrael than to be alone in Gan Eden,” was his answer.

Rav Nota was well known for his vast proficiency in hilchos gittin, the intricate laws of Jewish divorce. But for Rav Nota, knowledge and proficiency were a beginning, not an end. As he forayed into the world of halachic divorce, he began to take on a much larger role. Since halachah requires that a get be issued and accepted voluntarily by both parties to the marriage, dealing with the often nuanced and terribly painful scenarios became Rav Nota’s job as well.

No one man can tell all the stories of how Rav Nota managed to procure gittin against any possible odds. He went anywhere for that purpose, including behind Russia’s Iron Curtain. Over the years, it became common knowledge that all you need to do is ask, and Rav Nota Greenblatt would spend days on the road, taking car, train, bus, or plane, just to ensure a kosher divorce. He’d charge a modest fee for each get but never asked for reimbursement for his travel expenses. It was so in line with his character that no one ever thought to question it.

Rav Nota was not one to brag but he’d share a few stories with great emotion. He was once asked to intercede on behalf of a woman who had been trying to procure a get from her husband for 13 years. The woman, who had no children from the marriage, explained that she wanted to be able to marry again, as “she just wanted to give birth to a Jewish child.” Rav Nota called the husband, who explained that the logistics would be difficult seeing as he only left work at 8:00 p.m. Rav Nota recognized the tactic and responded in kind. “Not a problem,” he said calmly. They negotiated and agreed to meet at 11:30 p.m.

Rav Nota arranged for two witnesses to convene at the Anshe Sefard shul and they waited. And waited. At 1 a.m. Rav Nota instructed one of the witnesses, an elderly fellow, to go to bed. At 1:30 a.m. the man called, apologized, and explained that he had gone in the wrong direction. “Stay where you are,” Rav Nota replied, “I’ll come to you.” An hour later the fellow called, again apologizing. His car broke down and was now at the repair shop — a miracle of sorts since it was three in the morning. But Rav Nota was patient and the man finally arrived at 3:45 a.m. Rav Nota woke up the sleeping witness who arrived in his pajamas. The get was issued at a quarter to six.

Many years later, Rav Nota was visiting the East Coast and was approached by a young yeshivah student. “Are you Rabbi Greenblatt from Memphis?” he asked. Rav Nota replied in the affirmative. “I know that Rabbi Greenblatt helped my mother receive a get many years ago,” the boy said. “She remarried and had one child — me.” Rav Nota asked a few personal details and understood that this was the son of the woman from the pre-dawn get.

“And how is your mother doing?” Rav Nota asked.

“My mother? I just finished saying Kaddish for her,” the boy responded.

Rav Nota would cry when he’d tell this story, the fact that he helped bring yet another ben Torah to the world, an accomplishment that meant the world to him.

Once, a runaway husband had resettled in Europe, and Rav Nota managed to get him on the phone. Unwilling to go anywhere out of his way for the sake of freeing his wife, the fellow informed Rav Nota that he’d be traveling soon and would have some spare time in the Paris International Airport. Rav Nota immediately booked tickets to Germany. From there he’d take the train to Paris. He arranged for two witnesses to fly in from Eretz Yisrael and paid for their tickets. They met in the airport, the get was written, and Rav Nota proceeded to the woman’s hometown to deliver it. The woman’s rabbi asked Rav Nota how much money they owed him, but Rav Nota responded, “Azah mitzvah farkoift min nisht — such a mitzvah one doesn’t sell.”

On a different occasion, Rav Nota was involved in a local case where a husband left Memphis without halachically divorcing his wife. Rav Nota learned that this man’s mother passed away and that he’d be returning to town for the funeral that was set to take place on Erev Yom Kippur. Rav Nota headed over to the cemetery, arriving before the casket was lowered into the grave. Approaching the bereaved son, Rav Nota said, “We are not letting Mama into the ground until you write a get for your wife.”

The man consented, and Rav Nota allowed the burial to proceed. Immediately thereafter the get was written, and Rav Nota arrived back home with minutes to spare before the onset of Yom Kippur. His seudas hamafsekes consisted of an apple, but Rav Nota had no regrets. “Dos is gevehn mein zchus fahr Yom Kippur — this was my zechus for Yom Kippur.”

Rav Nota once remarked to his son nonchalantly that he received a check for $2,400 from the Israeli government as a reimbursement for his expenses in procuring a particular get.

“Dad, why?” his son asked.

Rav Nota explained that he was asked to help an Israeli woman whose husband had run away to Medellín, Colombia, a city notorious for drug gangs. Rav Nota first traveled to Bogotá where he got two witnesses, and from there, he traveled to Medellín, found the man, issued the get, and sent it to Israel. The Israeli government found out about this and called Rav Nota, trying to understand how on earth he’d pulled off such a feat. Rav Nota explained his simple formula, and the office of shocked Israeli bureaucrats informed him that they had a fund for people who assist in procuring gittin in difficult situations and sent him the $2,400 check.

Another time Rav Nota mentioned to his son that he’d traveled to Germany to issue a get, but not to worry, it hadn’t cost him anything.

“Didn’t cost anything? Dad, how so?”

“Because I used air miles,” Rav Nota responded.

The stories are endless, fascinating, inspiring, but also somewhat enigmatic. How did Rav Nota succeed when so many tried and resigned in frustration? The answer really goes to the core of Rav Nota’s essence. “My father’s only metric in any decision-making process was ‘What does the Ribbono shel Olam want?’ ” says his son, Reb Dovid. “There was no partiality, no likes or dislikes. Only the ratzon Hashem.” Rav Nota’s sincerity was so fiercely intense that it penetrated the impenetrable, granted him access to a place in people’s hearts long deemed inaccessible. Rav Nota succeeded because he cared so, so much. With every fiber of his being, he cared about the endurance and continuity of kedushas Yisrael. It was that burning passion that allowed him to move mountains, split seas, and ultimately succeed.

One of Rav Nota’s sons wanted to emulate his father in some small way, to move out to a community with little religious presence and make an impact. He asked his father which city he’d recommend.

“Ich volt gegangen in El Paso,” said Rav Nota, “I would go to El Paso.”

“El Paso? Daddy, what’s in El Paso?”

“Drei alte Yidden,” was Rav Nota’s response. “Three old Yidden.”

Rav Nota’s point was clear. Don’t look for numbers. Look for Yidden. Each Jewish soul is a universe, well worth your time and efforts.

But, aside from hashkafah, Rav Nota’s personality and public perception also played a crucial role. Because, towering as his scholarship was, Rav Nota never came across as rabbinic. He dressed like the commonfolk and, more importantly, spoke like the commonfolk. He was very much a living embodiment of his rebbi’s direction: “If your intentions are pure, and you know where you’re headed, and you know how to talk to people, there’s nothing in the world you can’t accomplish.”

Above Time and Space

The Aron Habris, we are taught, stood at the center of the Kodesh Hakodoshim, yet was eino min hammidah; somehow, its existence did not take up any physical space. The Aron, endowed with the holiness of Torah itself, shared its same quality of transcendency, the all-spiritual reality that might coexist in a finite world but will forever hover beyond it. Rav Nota’s lifelong hasmadah can only be explained as eino min hammidah. It existed everywhere, anywhere, and all he accomplished seemed to happen alongside his endless engagement with limud HaTorah.

Even as a young child, Rav Nota stood out for his outstanding diligence, leaving for the beis medrash early in the morning, only to return late at night. This characteristic never left him; everywhere and anywhere, Rav Nota Greenblatt learned.

Rav Nota was once in the airport with nothing other than a Chumash. His flight got delayed, and so he learned Chumash with Rashi — for ten straight hours.

A prominent mesader gittin once sent a letter to Rav Nota, describing a complicated question in hilchos gittin. He received a letter in response, intricate and brilliant, along with a small notation stating that, as he writes this, he is “baderech on an airplane.”

Rav Nota didn’t just learn — he loved to learn. A son once described that, growing up, it was hard to learn with their father because, at their young age, they were still struggling to find the joy in Torah while Rav Nota “just enjoyed it so much.”

The many letters of responsa that he wrote were never sent for publication; Rav Nota only published one sefer on Chumash called K’reiach Hasadeh. It’s not a particularly large sefer in terms of page numbers but it’s replete with the bursts of brilliance that were Rav Nota’s trademark. Rav Nota never sold the sefer. He would give it out personally, “on condition that you learn from it.” Although it’s formulated as a sefer on Chumash, it contains many ideas on various halachic topics, written with the condensed concision reminiscent of Brisk.

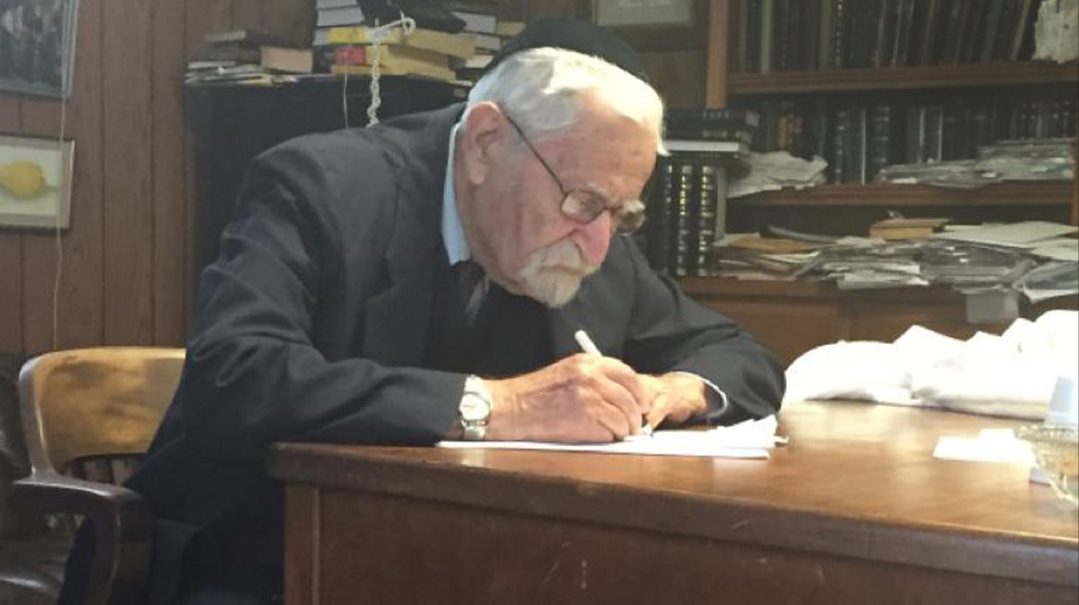

Whether with his beloved yeshivah or busy fielding sh’eilos, Rav Nota was always where he had to be

A Yeshivah of His Own

In 2014, when Rav Nota Greenblatt was 87 years old, he founded a yeshivah in Memphis, which may not have enjoyed the fame and longevity of Brisk and Mir, but was markedly successful in its own right. The yeshivah was named “Yeshivah Gedolah of Memphis,” the simplicity of the name just another testament to Rav Nota’s lack of interest in any sort of extravagance.

It happened almost by itself. A group of yeshivah bochurim spending a summer bein hazmanim in the Smoky Mountains of Tennessee went to daven Shacharis in the Chabad of Knoxville, Tennessee. The rabbi, Rabbi Yosef Wilhaum, asked if they’d be willing to volunteer to serve as witnesses to a get being given later that week. Having never seen the process before, the boys were intrigued by the opportunity. They arrived at the given time and were introduced to Rav Nota for the first time. Before starting the get process, Rav Nota launched into an hour-long shiur on hilchos gittin. Following the issuance of the get, the conversation continued, with questions being asked and incisive responses immediately delivered.

It was 10:30 p.m. when Rav Nota announced that he had to begin the six-hour drive back to Memphis. Not quite believing what they had just witnessed, the boys decided they must keep up with Rav Nota and, through that, the idea of establishing a yeshivah in Memphis was conceived. Several boys from Brisk, Mir, and Ner Yisroel of Baltimore committed and headed off to Memphis for what they later described as one of their most incredible years in yeshivah.

Rav Nota, scion of the greatest roshei yeshivah in modern history, who left yeshivah for 70 years to tend to Klal Yisrael, was back. Nothing could make him happier.

The yeshivah was based in Young Israel of Memphis, and there, Rav Nota delivered a shiur seven days a week, sometimes for up to three consecutive hours. Once, a talmid raised a question on the sugya, and Rav Nota was completely consumed by it. By evening, no answer was in the offing, and Rav Nota announced that he would not be giving shiur the next day unless he found the answer.

The next day Rav Nota entered the shul, face beaming. “I was up the whole night last night, and I have a mehalech in the sugya,” he told the talmidim. “Come, let’s say the shiur.”

Rav Nota once shared a particularly complex and brilliantly developed idea on the topic of Maaser Sheini. When he finished he began to cry. “It’s been 70 years since I thought of this shtickel, and now I’m able to share it with a new generation of talmidim.”

They Needed Him

Rav Michel Feinstein once commented that “volt Rav Nota geblibben in yeshivah volt ehr gevehn der greste Rosh Yeshivah — If Rav Nota had stayed in yeshivah, he would have become the greatest rosh yeshivah.” Rav Nota was acutely aware of this potential but he consciously chose otherwise. Klal Yisrael needed him. They needed his confidence, they needed his wisdom, and most of all, they needed his overwhelming love and concern.

But this year, on the 28th day of Nissan, as his magnificent neshamah ascended Heavenward, an empty seat was placed in the mizrach vant of the Mesivta D’Rakia, making space for Der Greste Rosh Yeshivah.

At Rav Michel Feinstein’s wedding. Rav Nota is in the far left corner, the tall man in the white hat

The Tenth Man

Rav Nota’s concern for the chinuch of Jewish children extended well beyond his hometown. Impressed by the success Rav Nota achieved in Memphis, in 1958 Dr. Joseph Kamenetzky of Torah Umesorah asked that Rav Nota work his magic for the community in Kansas City. Although it was home to a large number of Jewish immigrants, it had no Hebrew day school.

Rav Nota arrived in Kansas City at the beginning of the week, ready to give it his all. His first stop was the rabbi. Rav Nota approached him and asked his permission to recruit families for a potential Hebrew Day School. The rabbi looked at him and laughed. “The parents want nothing to do with the old country,” he said. “They want their sons to be American boys, with a proper education.” Rav Nota stood his ground, though, insisting that it was worth a try.

Finally, they came to an agreement. “Get ten families to sign up for the school by Friday, and the school is yours,” the rabbi said. “Anything less than that is not a school.” Rav Nota had one week to recruit ten families in a foreign city to commit to sending their children to a Hebrew day school that did not yet exist. He went from door to door, begging, pleading for the families to send their children. Many laughed at him. Undeterred, he continued, barely eating anything.

By midday Friday, he arrived at the rabbi’s home, famished and exhausted, but triumphant. Waving a sheet of paper at the rabbi’s face he proudly declared, “I have your ten applications!” The rabbi, who didn’t want the school to become reality, turned white. He began going through the list, name by name. Suddenly, he stopped.

“This family, Blumenthal, doesn’t count,” he said fiercely. “They live on the other side of the tracks, in the poor neighborhood; they don’t even have a floor in their home. He doesn’t belong with the other children.”

Rav Nota left broken. He asked his wife if he could be buried with these ten applications when he passed away, to show the Ribbono shel Olam something he did just for Him, with no possible personal gain.

Years later, when Bill Clinton was elected president of the United States, Rav Nota read that one of his cabinet members was a fellow by the name of Blumenthal. After doing some research he determined that this was, in fact, the Blumenthal child that would have attended the Kansas City school had it been allowed to open.

When relating the story, Rav Nota would begin to cry. “You know what potential this child had? From a home with no floor to Clinton’s cabinet? Who knows what a gaon he could have become? But he didn’t have the opportunity. Why?! Because of the rabbi. That rabbi! Even in Gehinnom there’s no place for him.”

Special thanks to Feivel Schneider who spent many hours gathering and providing much of the information contained in this article.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 912)

Oops! We could not locate your form.