The Highest Truth

| March 18, 2025Rav Shimon Schwab cherished his German minhagim, and everything else rooted in Torah

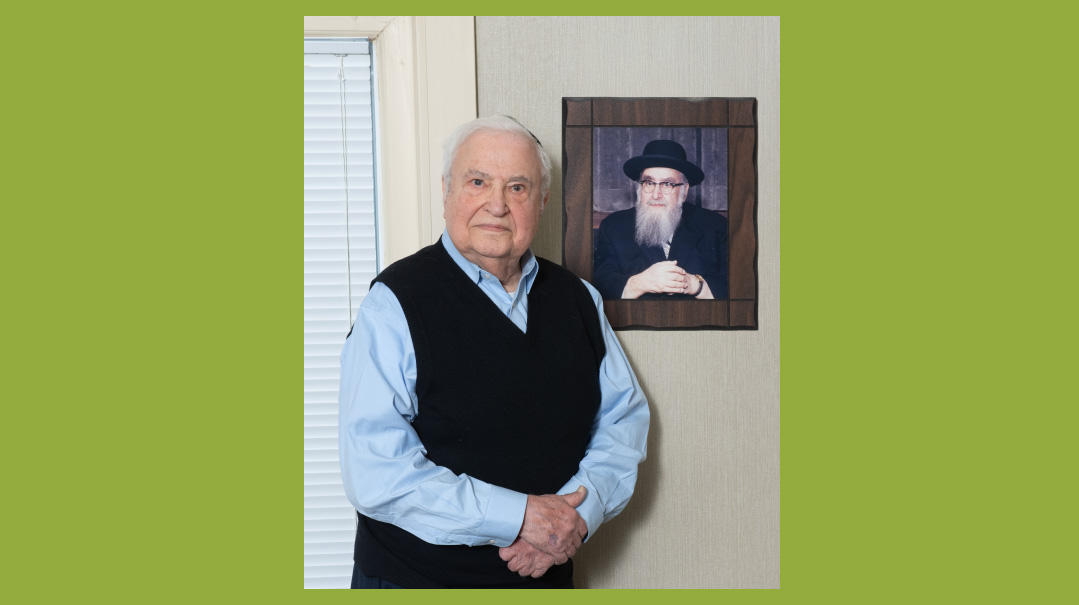

Photos: Jeff Zorabedian and Family archives

HEwas a leader of kehillos in his native Germany long before heading his flagship Khal Adath Jeshurun in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan. A man of impeccable in-tegrity, he was raised with the rich Hirschean mesorah yet learned in the great Lithuanian yeshivos, and while he cherished his German minhagim, he valued everything that was rooted in Torah. In tribute to Rav Shimon Schwab on his 30th yahrtzeit.

This Purim marked the 30th yahrtzeit of Rav Shimon Schwab, one of the great gedolim of the last generation. A leader of kehillos in his native Germany and then later in Baltimore, he led Khal Adath Jeshurun in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan, New York, with clarity, commitment, and compassion for the last 37 years of his long and productive life.

Rav Schwab was a foremost expositor of authentic Torah hashkafah in his time, expressing complex and nuanced ideas in elegant English, despite having only learned the language later in life. He was raised with the rich mesorah and Weltanschauung of Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch, the great “Rabbiner” of Ashkenaz Jewry and proponent of Torah im derech eretz, yet at the same time he was fully committed to intense limud haTorah in the mehalech of the great Lithuanian yeshivos.

“My father cherished the German minhagim, especially those that were emphasized by Rav Hirsch,” says Rabbi Moshe Schwab, Rav Shimon Schwab’s eldest son, in a conversation with Mishpacha about his revered father’s life. “But he also said there were other traditions we can learn from, and we should be open to everything that has its basis in Torah and mitzvos and mussar. He himself was a synthesis of the traditions of Rav Hirsch together with the mussar of Rav Yerucham and the Torah of the litvishe yeshivos. He cherished everything that made sense as long as it was deeply rooted in Torah and halachah.”

A man of unimpeachable integrity and truth, in both his personal and his public life, Rav Shimon Schwab supported Agudath Israel of America and delivered brilliant shiurim on Tanach, tefillah, and timely hashkafic topics. His leadership and his many published works left indelible impacts on his beloved kehillah in particular and on American Torah Jewry in general. On Purim Katan of 1995, at age 86, Rav Schwab succumbed to a severe heart attack he had suffered the day before.

R

abbi Moshe Schwab presides over Schwab Company LLC, the insurance agency he founded over five decades ago, and we meet in his office high above Boro Park’s 13th Avenue and 48th Street. Save for intermittent horns honking, the dignified atmosphere in the office belies the frenetic mercantile artery below. The furnishings and trappings, like its occupant and the community from which he hails, are quality, simple, and discreet — including a small, glass-covered hazelnut table adjacent to his desk.

As our conversation gets underway, the focused, active nonagenarian Reb Moshe looks longingly at the table.

“That was the very table that my parents had when they got married in Frankfurt in 1931,” he says. “And they took it with them to Darmstadt, then to Ichenhausen, then to Baltimore, and finally to Washington Heights in New York, before it ended up here. This is where we ate as kids, and it was at this table that gedolim, including Rav Elchonon Wasserman and the Ponevezher Rav, sat.”

He indicates the very spot where the venerated Baranovich Rosh Yeshivah sat. “If only that table could talk,” he says, his voice strong and steady. “It would tell a history of almanos and yesomim and gedolim, of all kinds of people who came penniless from Germany and came to my parents, who were an open house for all these refugees, helping them get them housing and employment and shidduchim. And because during the week my father was always busy with giving shiurim and going to meetings, it was on Shabbos and Yom Tov, around this table, that we received our main chinuch. My father would sit with us for two or three hours, during which we discussed Torah and told stories, sang, and conversed about the politics and the issues of the day.”

The inanimate table can’t share the stories it witnessed, the middos, the wisdom, the Torah, and the integrity absorbed into the wooden planks that withstood one of the most tumultuous centuries of Jewish history and traversed two continents. Thankfully, though, Rabbi Moshe Schwab can. The author of Rav Schwab on Prayer, Rav Schwab on Iyov, Rav Schwab on Ezra and Nechemiah, Rav Schwab on Yeshayahu, and the introduction and a portion of the Lashon Hakodesh Iyun Tefillah — all transcriptions of his father’s shiurim — Reb Moshe was not only a witness to much of his father’s fascinating life journey, but he is an accomplished talmid chacham in his own right, possessing a deep grasp of his father and his principles.

Oops! We could not locate your form.