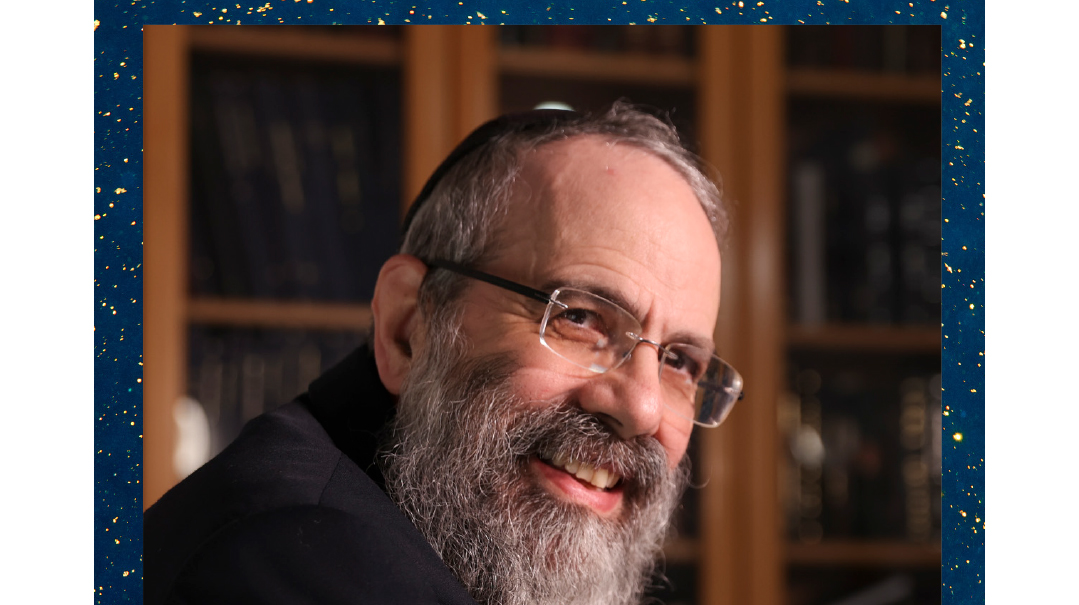

The Highest Notes

| July 8, 2025In tribute to Avi Piamenta a”h

F

or the last decade, from the time guitarist Yosi Piamenta a”h passed away in 2015, Avi Piamenta — one of the most beloved Jewish musicians of the generation — did his best to keep his brother Yosi’s legacy alive. Yet with Avi’s sudden passing last week at age 69, the curtain finally came down on the famed Piamenta Brothers — but the music they created and the inspiration they instilled over a span of 40 years will surely live on.

For Avi, who lived in Kfar Chabad since the early ’90s, the initial fame and ensuing spiritual odyssey was intimately tied to his brother, who created the band’s signature style — rock-influenced chassidic and Israeli music with a warm, friendly, and happy message.

“Our uncle Albert Piamenta was an Israeli saxophonist who became famous for mixing Judeo-Arabic music with jazz,” Avi told Mishpacha in an interview last year. Their father, Yehuda, was a Shin Bet agent, and although no one knew exactly what he did, after he passed away in 2011 at age 84, Prime Minister Bibi Netanyahu called his sons and told them that although their father always worked in closeted secrecy, his accomplishments for the country’s security were significant.

While the Piamentas had 17 generations behind them in the Holy Land, the boys knew little of their heritage. Avi grew up playing piano but eventually, he said, “I discovered the magical sound of the flute and that became my instrument of choice.” Music was the dominating force in his life, and when he was 17, he started performing with his brother Yosi, four years his senior, who’d already made a name for himself in the competitive and often cutthroat circle of professional guitarists.

The two of them formed the Piamenta Band and soon became crowd favorites on the secular entertainment scene, both in Israel and abroad.

“But even then,” Avi said, “before we became close to the path of Torah, we also played songs with Jewish traditional phrases that we were familiar with. It just seemed natural to include them in our playlist. Perhaps it was in the zechut of our grandfather Avraham, who worked hard to imbue us with some tradition, even though we were pretty far from Yiddishkeit growing up.”

In 1976, the brothers got their big break when famed American saxophonist Stan Getz came to Israel as part of a European tour. He was so excited when he discovered the Piamenta brothers that he canceled all his upcoming European events and stayed in Israel to record an album with them.

Meanwhile, Yosi and Avi became connected with music producer Shaul Grossberg, an industry legend involved with the biggest names in Israeli rock of the ’70s and ’80s. Grossberg had a nightclub where he featured the top tier of secular music, and Yosi and Avi were booked as regulars, playing with some of the most radical artists at the time, although Avi noted happily that “many of them became chozrim b’teshuvah later on.”

In 1978, for the 30th anniversary celebrations of the State of Israel, the Israeli government sent the brothers to perform at sponsored events throughout the US and Canada. Around that time, both Yosi and Avi had become Torah-observant, and were soon exposed to the teachings of Chabad chassidus. They decided to stay in New York to learn Torah, and even formed an informal yeshivah with other musicians. Eventually both of them moved to Crown Heights.

“This was the beginning of the great change in our music,” Avi related. “We rebranded ourselves, learned the language of the chassidic niggun, and began including chassidic songs in our repertoire, developing our own unique style. At that point we wrote to the Lubavitcher Rebbe asking if we were on the right track, bringing estranged Jews back to Judaism through music, and the Rebbe encouraged us, giving us specific instructions for how to inspire and yet make sure to maintain moral fences in an industry that has no restrictions at all.

“Veteran arranger Yisroel Lamm once told me that he first met Yosi at a concert in San Diego with MBD, where Yosi on guitar and Avi on flute were the opening act,” longtime producer Dovid Nachman Golding (a.k.a. Ding) relates. “MBD and Yisroel were backstage when they first heard Yosi playing, and right then, they both knew that Yosi was in an entirely different league than all other guitar players. After the concert, they approached Yosi together and told him that if he moved to New York, he would be in demand for weddings and concerts every night. I’ll never forget the Piamenta brothers’ surprise entrance at the second HASC concert, when they came on stage to perform their famed "Asher Bara" song. The audience went wild. Sheya Mendlowitz a”h, who later made several albums with them, matched the tune with holy words — he just knew from day one that it would be gigantic.”

W

hile Avi was admittedly far from Yiddishkeit growing up, he says tradition always had a pull. “One thing I always did was put on the tefillin my grandfather had bought for me,” he said. “But then I’d ask myself, ‘Who are you kidding? You don’t observe any other mitzvot.’ One day, I found a sefer someone gave me for my bar mitzvah, the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch. I opened it for the first time, and I was shocked. Suddenly I read about all sorts of things that I was obligated to do, and realized how far away I was. I closed it and told myself it’s better for me not to know, than to know and not keep anything.

“At the time,” Avi related, “I was studying at a music academy in Tel Aviv, and I had a teacher who was chozer b’teshuvah. One day I decided to confide in him. I told him that I put on tefillin but I feel deceptive about it, and that I’m scared to learn anything because I don’t want to be obligated to keep it. Then he shared something that calmed me down: ‘If one day you think you might keep mitzvot, then you’re allowed to learn about them, even if you’re not observing what you learn.’ ”

For a long time, even as Avi moved closer to tradition, it was one foot in both worlds. “For example,” he said, “I would travel to musical events on Shabbat, but I made sure not to switch the light on in the stairwell. Later, when I stopped driving, I would walk to events, but I played as usual. At the time, I had lots of questions, so for example, when I played in a restaurant that wasn’t strictly kosher, I remember wondering if I had to make a brachah on the food or not.

“The truth is,” Avi Piamenta added thoughtfully, “in retrospect, I think HaKadosh Baruch Hu takes pleasure in these dilemmas. After all, every Jew wants to come back to Him, and sometimes the path is long and winding. When you draw closer to holiness, there will always be things that try to deter you. For me it happened when my brother and I had a string of gigs with one of the biggest producers in the country. We were supposed to play all over and we had already signed a contract. But at that time, we were starting to become more observant, and I decided I wasn’t working on Shabbat anymore. It was very uncomfortable to inform the producer, and I knew I was messing up all the members of the band, because I played the keyboard and the flute, and there was no way they could perform without me. In the end, they had no choice — we only booked for weekdays. The amazing thing was that a few months later, we found out that all the members of the band had stopped working on Shabbat.”

Avi always said it was no coincidence that so many musicians find their way back to Yiddishkeit. “It’s because musicians are very spiritual people,” he explained. “Although they have a reputation for being leftists, they’re people with great inspiration and highly developed emotions. And I believe that any artist will tell you that when they compose songs, they feel that it really is not from them — it’s something they bring down from Above, however they interpret that. I think every talented musician has this feeling at some level, that he was granted the privilege of bringing his music into the world.”

Avi, the privilege was ours.

— Mishpacha Staff

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1069)

Oops! We could not locate your form.