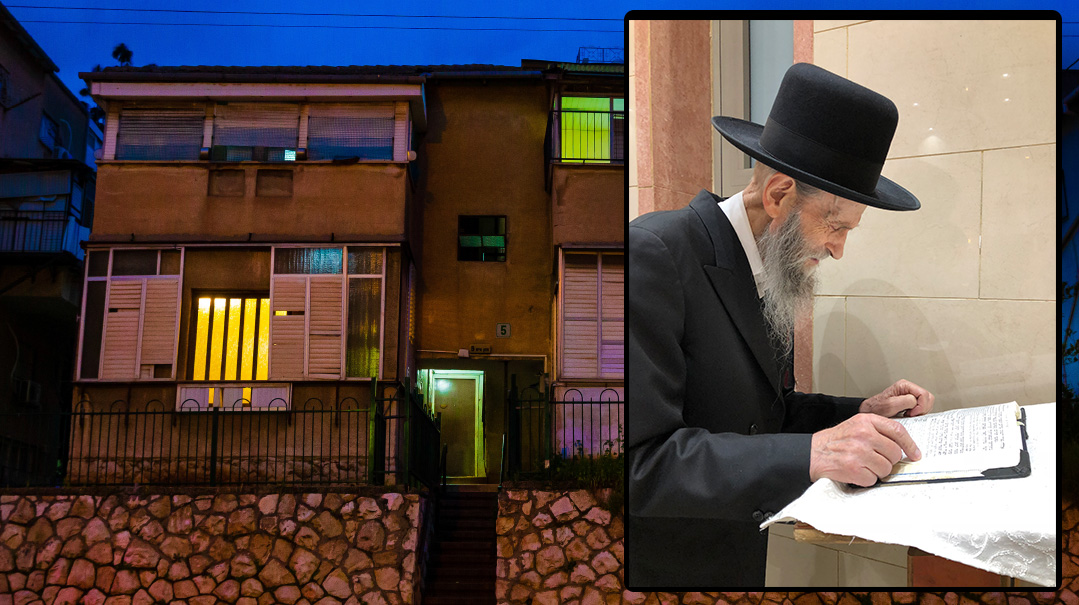

The Hidden Tzaddik of Chazon Ish 5

The thousands who came to Rav Steinman's home were unaware that upstairs, Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski’s modest demeanor hid the splendor of the last prince of Slabodka

When a bankrupt contractor walked away mid-job from a small building project in Bnei Brak in the 1950s, the four young couples who had bought apartments on paper didn’t have much choice. Cash was scarce, and the families banded together to move into the unfinished shell. Slowly the apartments were completed by laborers after their day shift on the building site of a nearby yeshivah.

Having left the buyers to fend for themselves, the contractor didn’t dream that he’d just built an icon: a modest building, that 70 years on, feels like a museum of Torah greatness.

Those unpainted pebble-dash corridors and bare concrete walls watched as hundreds of thousands of Jews passed by to speak to one of the occupants. In the last decades of his 104 years, Rav Aharon Leib Steinman’s spartan apartment at Rechov Chazon Ish 5 became famous as the address for Jewish problems.

The thousands who climbed the steep stairway to the building may not have realized, but the other apartments had illustrious residents, too. Next door to the Steinmans lived the Levensteins; Rav Yitzchok Levenstein was Rav Steinman’s longtime gabbai.

One floor up, a sign on the door carries the name “Yisraelson.” Rebbetzin Yisraelson answers the door. She’s the almanah of Rav Yosef Yisrael Yisraelson, who passed away 12 years ago. The well-worn seforim and extreme simplicity of the apartment speak of a life dedicated to learning. On the wall, an early photo montage of the Ponevezh yeshivah shows her husband along with a host of now-famous names, all still in the flush of youth as bochurim.

But Rebbetzin Yisraelson is also the daughter of Rav Elyashiv. She points to the picture of her great-grandfather, known as the Leshem, and tells the story of his promise to his own childless daughter that she’d have one son who would light up the world.

“We always thought that we’d be orphaned young, because my father had a weak heart,” she continues, “yet he lived until 103. The thing we heard most often as children was, ‘Shhhh… der Tatte lehrnt.’ "

When asked about her neighbor, Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski, who lived in the apartment next door until his sudden passing a year and a half ago, she says simply, “Rav Grodzinski was a tzaddik — what else is there to say?”

One floor up from the epicenter of the Torah world lived someone extraordinary in his own right. Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski, known to the world as a humble, smiling rosh kollel, was in fact the last prince of Slabodka.

Rav Yitzchak’s father, Rav Avraham, who succeeded the Alter as head of the legendary Slabodka yeshivah alongside Rav Eizik Sher, was given the ultimate accolade. “There are many who succeed in breaking their middos, but one hears the crack,” said the Alter. “With Rav Avraham there’s no sound.”

Raised in the rarefied atmosphere of Slabodka and by his father’s side until the latter was killed in the Kovno ghetto during the Holocaust, “Itzeleh Grodzinski” possessed a certain purity that was reflected in his fine features.

As a frail teen, he risked his life smuggling sacks of potatoes into the ghetto, and his faith-saturated niggunim were remembered half a century later by his peers. He was there when Rav Elchonon Wasserman was taken to his death, and he survived Dachau to bring the songs of Slabodka to the postwar Torah world.

His hours-long tefillos were legendary, and the lengths he went to fulfill mitzvos were extraordinary, as was his care for others. In an uncanny way, he was Yitzchak to his father’s Avraham; his whole life spent carrying the torch that his father lit.

But simultaneously, as his wife of 6o years says, he was hidden. He hid his learning, he disguised his fasts, and he closed the door on his past. And his authentic chassidus was a startling contrast to his Slabodka background.

To understand Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski, one needs to open the sefer that he lived and breathed — the half-forgotten work of his father, called Toras Avraham. It’s a demanding work of gadlus ha’adam, the greatness of human potential, in the Slabodka tradition. These were the ideas that shaped him in his childhood; they accompanied him as he faced the Nazi hell and defined who he was to the end of his days.

My own encounter with Rav Avraham Grodzinski’s mussar gem led to a tentative appointment to meet the author’s son — a meeting that never materialized due to Rav Yitzchak’s sudden passing.

Instead, the following is a journey into his life through the fragments he told his family, the hints that emerge from his father’s work, and the silent message of that small apartment on Rechov Chazon Ish.

Building Harmony

When that long-forgotten contractor jumped ship, a unique bond developed between the young Grodzinski family and the other residents of Chazon Ish 5. Just outside the developing town, the area was surrounded by orchards, and infested by jackals — probably the reason the building was designed with a steep stairway. So the men of the building took turns guarding the exposed, still-incomplete structure — and Rav Steinman took shifts as well.

From their small size to the tiny kitchen drawers and olive-green woodwork, the apartments still bear the stamp of their austere 1950s origins. But simplicity went along with neighborliness. “In all the years we lived together, we never argued,” says Rebbetzin Yisraelson — no small feat in the annals of Israeli apartment dwelling.

The harmony was also complemented by music. During one of Rav Elyashiv’s rare trips to Bnei Brak, he stayed with the Yisraelsons, and the musically inclined gadol was struck by the notes coming through the thin walls. Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski’s clear voice, repeating over and over again, “Ana avda d’Kudsha Brich Hu,” was entrancing.

The Grodzinskis raised a family of eight in two-and-a-half rooms; the children’s room, containing Rebbetzin Miriam Grodzinski’s own small desk, reflects her lineage. As befitting a daughter of Rav Mordechai Zelivansky, whose father-in-law Rav Aryeh Shapira was part of the Volozhin dynasty, one wall is covered with the portraits of litvishe matrons in 19th-century bonnets — her forebears. The other wall contains a small desk and her own store of seforim. “It was a house of learning, and my mother was my father’s chavrusa,” their daughter Rebbetzin Kook relates with a smile.

Her mother refuses to divulge what they learned — “We learned many seforim!” she says. But there’s one thing she emphasizes, eager to dispel the impression that the Holocaust, which overshadowed Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski’s early years, dominated her home. “Despite his experiences, my husband was full of simchah,” says the rebbetzin. “He was always warm and smiling.”

Behind Closed Doors

Some time after the war ended, a teenaged Itzeleh Grodzinski stood by the seforim shelves in Jerusalem’s Chevron yeshivah and began to cry. The rosh yeshivah, Rav Eisik Sher, who was the Alter of Slabodka’s son-in-law, went over to him and asked what was wrong.

“When I look into the Gemara, all I see is blood,” was his chilling reply. Fresh off the boat from the Holocaust, the rivers of blood washing before his eyes were his father, siblings, and the world of Lita that he’d known.

Then came the words that changed Yitzchak Grodzinski’s life. “Farmachen und effenen,” said Rav Sher. “You have to close off that world and open a new one.”

Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski spoke little of the past — he’d walled it off. Asked in later years whether he would go back to his birthplace, his response reflected that suppressed longing. “How much I want to go back to see it and how much I don’t want to,” he said.

The Slabodka that Itzeleh Grodzinski was born into in 1928 was a place of wooden shacks and 6,000 Jewish souls. But on the Torah map of the world, this poor suburb of Kovno was a giant metropolis, because of its yeshivah.

Slabodka’s alumni list is a glittering who’s who of greatness. Rav Aharon Kotler, Rav Tzvi Pesach Frank, Rav Yitzchak Hutner, Rav Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg — the names are testament both to the institution’s elite status and to the Alter of Slabodka’s educational approach that allowed diversity to flourish.

By 1928, when Itzeleh was born, his father, Rav Avraham Grodzinski, was at the helm of the yeshivah. Born in Warsaw in 1884, his own father Reb Itzeleh — after whom Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski was named — was a tzaddik who became close to the Chofetz Chaim when the latter came to sell his seforim in the city.

Rav Avraham was an extraordinary person; he had a combination of towering Torah knowledge and deep understanding of human nature. He entered Slabodka at 17, and the Alter, Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel, soon considered him a leading talmid. He was sent to bring the mussar approach to Rav Eliezer Gordon’s Telshe yeshivah, and when he returned, he was appointed a mashgiach under the Alter.

Rav Avraham Grodzinski’s meteoric rise in the Slabodka firmament was sealed in 1911 when he married Chasya, the daughter of the yeshivah’s other mashgiach, Rav Dov Tzvi Heller, a talmid of both the Alter of Slabodka and the Alter of Kelm.

Noteworthy in Rav Avraham’s work is its extensive focus on suffering and its place in personal growth. Yissurim struck the young Grodzinski family hard. When Itzeleh was just a year old, Rebbetzin Chasya fell seriously ill. Taken to Koenigsberg, Germany (now Kaliningrad, Russia) for medical treatment, the young mother — herself a scion of mussar royalty — had an unusual vision. “I can see Rav Yisrael Salanter,” she said.

The treatment didn’t help and she died in the city, where she was indeed buried near the founder of the mussar movement. Rav Avraham waited two days to say the brachah of Dayan HaEmes after his wife’s passing, to prepare himself properly for the moment.

He was left to raise their eight children alone. The orphaned Itzeleh, barely a toddler, was sent to his mother’s sister in the small town of Tzitavyan for a year. His aunt, Rav Dov Tzvi Heller’s other daughter, had married Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky. When the Kamenetskys left for North America, Itzeleh was sent back to his father in Slabodka.

But it was the start of a lifelong relationship with the Kamenetsky family. “Rav Yaakov visited us in Bnei Brak, and saw me taking care of five pitzkelach and washing all of the children’s laundry by hand,” says Rebbetzin Miriam. “He said, ‘You need a washing machine,’ and he bought us one. He felt a responsibility for my husband.”

Rav Avraham Grodzinski, Papa to his children, never remarried, and raised a young family alone while heading a major yeshivah. It demanded major strength of character, but his success is evident in the caliber of the men who married his daughters. Rav Chaim Kreiswirth, later the rav of Antwerp, Rav Shlomo Wolbe, and Slabodka rosh yeshivah Rav Boruch Rosenberg all became his sons-in-law.

In Slabodka circles, the choice of Rav Kreiswirth was considered particularly noteworthy. “Rav Chaim was a Galicianer, and people expected Rav Avraham to take a son-in-law from Slabodka,” says Shlomo Kook, Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski’s grandson. “But Rav Avraham wasn’t interested in sectors of Klal Yisrael. He chose Rav Chaim Kreiswirth because he was an incredible lamdan.”

Another hint of Rav Avraham Grodzinski’s chinuch approach comes from Itzeleh’s childhood friend and fellow survivor of the Kovno ghetto, Rabbi Yitzchak Gibraltar. He recalled his friend Itzeleh’s bar mitzvah drashah: in place of a deep pshetl, he “listed the entire 613 mitzvos that he’d learned by heart.”

And like everything that Rav Yitzchak Grodinski learned from his father, he passed it on to the next generation. “Whenever we came to help him,” recalls another grandson, Motty Kook, “he would go through all the mitzvos that we were doing. Vehadarta pnei zakein, gemilus chasadim — that was his constant refrain.”

A World in Ruins

In the early summer of 2002, I found myself, between high school and yeshivah, staring out over the Neman river that divides Kovno from Slabodka. A elderly Jewish guide, Kovno-born and bred himself, told the local story in his deep Lithuanian accent.

We visited the Seventh Fort, a Tsarist era-stronghold, one of many that ring Kovno, and the site of Rav Elchanan Wasserman’s murder. The vast field with its tens of thousands of Jewish victims buried in one mass grave under the green sward is silent testimony to the Nazi atrocities.

Now, fragments of that guide’s speech surface when I listen to Rav Yitzchak’s story as told by his family. “Aleksot,” a few miles away from the town, is where a teenage Itzeleh was forced to build a German airfield. “Bunker” must have referred to the tiny hideouts into which the Grodzinski family squeezed themselves as the SS and their Lithuanian collaborators marauded in their aktionen.

And then there’s Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski’s childhood home, the one he couldn’t bring himself to visit. “This is where Rav Elchanan Wasserman was when he was taken by the Germans,” said the guide, pointing to a wooden house.

In 2016, on the 75th anniversary of Rav Elchanan’s death, Rav Grodzinski agreed to break his silence and addressed Yeshivas Ohr Elchanan in Jerusalem.

“Rav Elchanan was in Slabodka because he’d come to visit his son Reb Naftali, who had broken his leg and was recovering in the hospital. In his last hours, I saw Rav Elchanan deeply involved in his learning, despite the horrendous screams outside as the Germans went from house to house. That first day, for some reason, the Nazis left our house alone.”

But it was only a short reprieve, because the next day, the Germans found the house of Slabodka’s most prominent Jewish leader. “The murderers suddenly entered our house,” he continued. “There was a debate between two of them whether to take my father or Rav Elchanan, and in the end they told Rav Elchanan to stand in the courtyard, which he did without resisting.”

The Nazis’ strategy was always to seize local Jewish leadership to leave communities rudderless, and Rav Avraham Grodzinski was the most prominent ghetto rabbi. So why did he survive that aktion and three further years of ghetto life? Rav Yitzchak himself saw it as an act of Divine hashgachah.

“He needed to live to the end of the ghetto,” Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski told the bochurim, “to strengthen the bnei Torah there, because he was a beacon of faith. He showed everyone that the Germans don’t decide who lives and who will get swept up in an aktzion, rather it’s all a Divine decree.”

When Hitler’s forces invaded the USSR in June 1941, the Lithuanian Holocaust began. Two months later, 30,000 Jews from Kovno and Slabodka were herded into the ghetto in Slabodka, forced to wear yellow stars, and sealed off from the world by barbed wire and armed sentries.

Slabodka’s descent into suffering elicited the greatness of its rosh yeshivah’s son. Death stalked the ghetto as men were shot for not getting off the sidewalk when Germans passed, or for buying food in the marketplace. And that’s when Itzeleh Grodzinski’s courage and faith emerged.

“Many times I shook with fear when I saw the self-sacrifice of my dear friend, the tzaddik Rav Yitzchak, for his father,” writes Rabbi Yitzchak Gibraltar in his book Yasor Yisrani.

“I was a messenger boy for the ghetto council, so I could move around, and I saw him enter the non-Jewish cemetery, take off his yellow star — itself a dangerous act — and evade the German sentry. He would slip out of the ghetto to bring some food for his father and sisters. He would walk calmly down the road outside the ghetto, because if he looked sideways or hurried, he would have been suspected. But he walked straight and trusted in Hashem.”

In the darkest of times, Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski uplifted others. “On those evenings,” writes Rabbi Gibraltar, “he transported everyone to another world. He had a beautiful voice that he used as chazzan for Yamim Noraim in Kollel Chazon Ish for decades. But I heard him in the ghetto, using his sweet voice to teach us new tunes. One was his famous “Al Tirah,” which he heard from a Polish refugee, which we sang for hours.”

That particular song, slow and heartfelt, became Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski’s anthem. “Al tirah mipachad pisom,” he would sing at family occasions, urging everyone to strengthen their trust in Hashem — a faith that had taken him through the darkness.

The belief that the tragedies he’d seen were directly from Hashem was something Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski believed on the deepest level.

“At a family simchah, his mechutan pointed to their shared grandchildren, and said, ‘This is your revenge against the Nazis,’ ” says Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski’s son-in-law Rav Benzion Kook, a well-known posek in Israel. “But he recoiled in shock: “Revenge?! I don’t know the Nazis! Everything came from Hashem.”

Land of Holiness

When Yitzchak Grodzinski’s boat docked in Eretz Yisrael not long after the war ended, it was a homecoming of sorts.

Two decades earlier, Rav Avraham Grodzinski himself had headed to the olive-green hills of ancient Chevron, on the Alter’s instructions, to establish a branch of the yeshivah in the holy city (though it met its tragic end after the 1929 massacre, when it relocated to Yerushalayim). He himself returned to Lithuania before those dark days, but his love for the Holy Land found expression in a letter that he drafted as the ghetto gates swung shut. After pondering why disaster had befallen European Jewry, Rav Avraham focused on 12 areas where mitzvah observance had fallen short. The 12th was “Eretz Yisrael.”

Rav Avraham Grodzinski’s list became his son’s roadmap. Already on the way to Israel, his extraordinary dedication to mitzvos came to light when he refused to change out of his concentration camp uniform because of his fear that the clothes that were offered to him contained shatnez.

“Someone told him, ‘You can’t travel like this!’ ” says his wife. “But he refused to listen, until the man sent him to the Klausenberger Rebbe, and he accepted his opinion that the suit was shatnez-free. That’s how he was throughout his life — he had emunas chachmim, and at the same time, would check every single item of clothing, even socks, and even synthetic materials.”

Kashrus came third on his father’s list, and Rav Yitzchak’s caution in that area was astonishing. Even in his later years, when he would be on the road for up to six months a year fundraising on behalf of Kollel Toras Avraham, which he founded in memory of his father, he never ate anything but his wife’s cooking. “I used to prepare 60 schnitzels for him, and they would be frozen and refrozen as he traveled,” she remembers. “The doctors said that that’s what damaged his digestive system, but even when he could no longer eat that because of illness, he’d take along his own pot and oil to boil vegetables.”

According to Rebbetzin Grodzinski, her husband shared little about his past. But one thing the family did learn: “He said that he’d never eaten treif during the war even in Dachau, although he’d eaten bishul akum. Perhaps he felt that he needed to rectify that.”

If Slabodka taught the idea of human potential, Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski embodied a rare tradition within the Lithuanian yeshivos — a holy tzaddik, who wore his greatness lightly.

Perhaps nowhere was that holiness more apparent than his tefillos. “Years ago, before they had their own shuls, all the gedolim, from Rav Chaim Greineman to Rav Nissim Karelitz, davened in Kollel Chazon Ish,” says the Rebbetzin. “My husband was the chazzan there, and the Steipler said about him that his tefillos were answered.”

The intensity of his Yom Kippur davening accompanied him throughout the year. Shacharis would begin at sunrise, and continue for hours. When he arrived to listen to Krias HaTorah midmorning in Lederman’s, the bustling shtibel around the corner from his home, those who didn’t know him assumed that he was late. A weekday Maariv had the aura of Yom Kippur. Bircas Hamazon could take half an hour, as he cupped his thin hand over his eyes and repeated over and over again, “Hu heitiv… hu meitiv… hu yeitiv lanu!”

A segment from Toras Avraham, his father’s work, sheds some light on his lifelong attitude to tefillah. As Rav Avraham taught his students in Slabodka, tefillah isn’t just a mechanism to fulfill one’s needs. It’s a global act of kindness.

Three times a day, taught the Anshei Knesses Hagedolah, a Jew needs to ask for mercy from the Creator on behalf of the entire world. Not just for individual needs, but for the whole world, for kibbutz galuyos, Mashiach, and the Shechinah. Because Man is great, and in accordance with his loftiness is his capacity to do kindness. The global kindness of prayer is an echo of that of Hashem’s kindness.

And on a lifelong mission to follow his father’s teachings, Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski’s tefillah became the ultimate expression of human greatness.

Life Lessons

It’s a brisk ten-minute walk from Chazon Ish 5 to another Bnei Brak landmark connected to the Chazon Ish.

Tiferes Zion, a large building on Rechov Yerushalayim, was the first litvishe yeshivah ketanah in the country, founded in 1935 under the direction of the Chazon Ish. His own nephews, from Rav Chaim Kanievsky to Rav Nissim Karelitz learned there, and the walls of this storied institution still echo with the Torah of young voices.

“When we were married a few years,” Rebbetzin Grodzinski relates, “my husband went to teach in Tiferes Zion. He treated every talmid like a son. He would bring the talmidim home to eat with us, and he regularly fasted for the success of his students.”

There was a talmid from a very rough neighborhood of Tel Aviv known as Hatikvah who was thrown out of the yeshivah. After Rav Yitzchak’s passing, the man —who became a stonemason who makes matzeivos — told the Grodzinski family the story of what happened next.

“Rav Yitzchak came all the way to Shechunat Hatikvah, and told me that he would get me back into the yeshivah, and took me back with him,” he said. “Hatikvah was a crime-filled neighborhood, a haunt of the Israeli mafia, and the fact that I’m religious today is because he took me out of there.”

Shortly before Rav Grodzinski’s passing he was reunited with another talmid who’d gone on to become a leading rav in Israel. Rav Shlomo Amar, the former Sephardi chief rabbi and now rav of Yerushalayim, was a student in Tiferes Zion in the 1960s, and recalled his teacher’s unique education methods half a century later.

“Rav Grodzinski never raised his voice, and never even told us off,” he said. “As teens somehow we were aware that he was a holy man, and so we behaved for him. He was a hidden tzaddik,” concludes Rav Amar. “Even those close to him didn’t recognize his full greatness.”

It was the Steipler who told Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski to open his own institution. “You’re an only son, so you need to open a kollel in your father’s merit,” the Steipler told him.

In the 1970s, Kollel Toras Avraham opened its doors and a new chapter began in Rav Grozinski’s life. Today numbering a hundred avreichim, the kollel focuses on the halachah-oriented approach advocated by Rav Avraham Grodzinski. It quickly became a home to many mature talmidei chachamim, and is considered a leading Bnei Brak institution. “He treated each avreich like an only son,” says his wife. “He would knock on the door of an avreich’s home, and tell the wife, ‘I know you’re short of money — take some.’ ”

And that money, hard-earned though it was as he trekked through North America and Europe for six months a year, was directly from on High, as he saw it.

“He had a unique attitude toward collecting,” says his son-in-law Rav Bentzion Kook. “When he met someone who was struggling to collect, say in London, he would take them to ‘his’ gevirim — the people he needed to support his own kollel — and introduce them. He didn’t worry about his own fundraising, because he was there to support Torah — it didn’t matter whose institution.”

Torah learning, chesed, faith in Hashem — it was as if Rav Avraham Grodzinski’s list of mitzvos, compiled in the blood and fire of the Slabodka ghetto, had converged to become his son’s lifelong endeavor.

Final Days

Two weeks after I’d put off my appointment to see the tzaddik of Chazon Ish 5, my wife and I were sitting in an ambulance as she was transferred, mid-labor, from one Jerusalem hospital to another. Doctors were concerned about something detected in a scan, and wanted better facilities for the birth.

My father-in-law in London, who was close to Rav Yitzchak, called to ask for his brachah that all should be well. Later that night, Rav Yitzchak called back to offer to call a doctor he knew in the hospital, to make sure we were getting the best care.

Shortly after, a healthy baby was born, and the next day, the phone from London to Bnei Brak rang again, but Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski wasn’t there.

“He’s been taken to the hospital,” his daughter said.

There in the ICU, the thin frame that had survived the concentration camps shook with cold. His eyes were closed, he was sinking fast, but when extra blankets were brought, he opened his eyes. “Who says they’re not shatnez?” he asked.

And with the unassuming holiness whose roots lay in his youth in Slabodka at his great father’s side, Rav Yitzchak Grodzinski left this world.

Shortly before Rav Aharon Leib Steinman had passed away, Rav Yitzchak had gone downstairs to him. With the gadol’s strength ebbing, the upstairs neighbor wasn’t sure of being recognized. “It’s Yitzchak Grodzinski,” he said by way of introduction.

“Of course I know who you are,” came the answer. “We’ve been neighbors for 50 years.”

“Will we be neighbors in the Olam HaEmes as well?” asked the last prince of Slabodka, and Rav Steinman’s reply confirmed his view of this hidden tzaddik. In the heavy Yiddish that they’d both taken from Lita, Rav Aharon Leib said: “M’stama, shecheinim down here, shecheinim up there.”

Inside the Toras Avraham

Like many mussar works, Toras Avraham is off the beaten path for today’s yeshivah world, partly due to the fact that the sefer has been out of print for a while.

The Grodzinski family are working on a reprint, and there’s more to come. A folder in Chazon Ish 5 contains the faded, typewritten draft of unpublished sichos from Rav Avraham Grodzinski. Yisrael Grodzinski, an older brother of Rav Yitzchak, prepared them before his death in a Nazi slave labor camp, and Rav Wolbe corrected many of the proofs.

The other reason that the work isn’t more widely known is the sefer’s difficulty. But in a generation that is thirsty for elevation, Slabodka’s themes of each person’s potential are more relevant than ever. Here are two excerpts:

Mind and Mitzvos

“Adam nolad v’sefer Torah imo — Man was born complete with a sefer Torah.” With that memorable phrase, Rav Avraham Grodzinski defines Slabodka’s approach to the human intellect. With all of our frailty, he says, a person is capable of discovering truth to the extent that a conclusion reached based on objective assessment of what mankind’s purpose is, has the same binding force as a mitzvah. That’s why punishments before the giving of the Torah — such as the Mabul — were so much more severe than for sins committed afterward. Because contravening basic human morality, which a person’s own intellect can fathom, is a violation of that sefer Torah, the human mind.

Making Work Holy

Why were Rabi Yochanan Hasandlar and Rabi Yizchak Nafcha, two sages of the Gemara, known by their profession? Was their work such a core part of their identity?

The answer, writes the Toras Avraham, is that the Amoraim’s work was a key to their spiritual journey. They became holy because they constantly asked Hashem for help in completing their professional tasks.

That, says Rav Grodzinski, is how being active in the world beyond the beis medrash can be turned into true spiritual growth.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 854)

Oops! We could not locate your form.