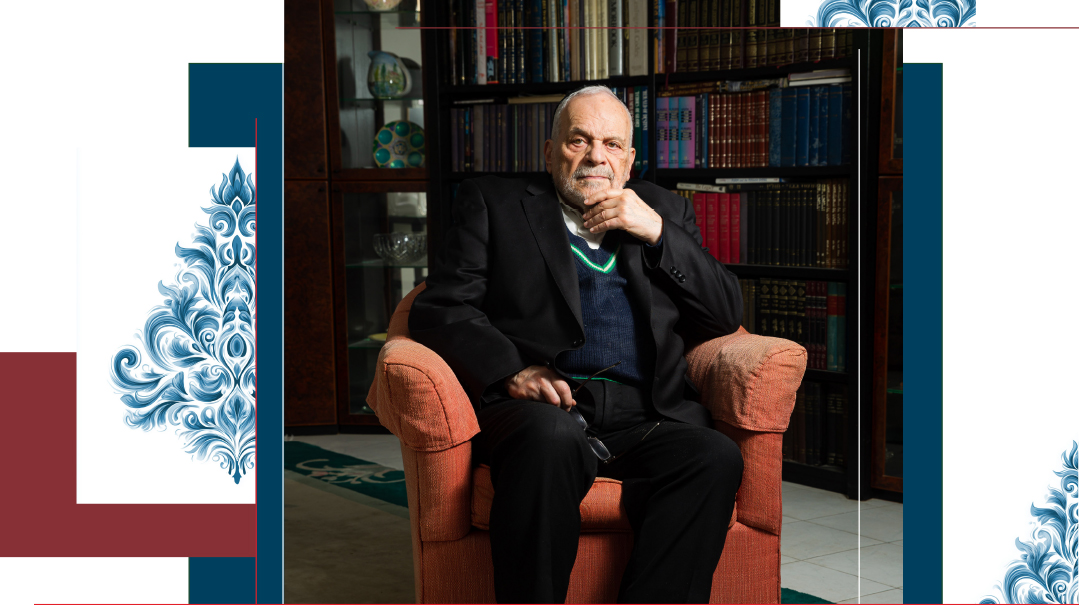

The Grand Sweep of the Past

That desire to “do for the Jewish People,” was nurtured in the Wein home

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Mishpacha and family archives

N

o rav in our time had the same influence across the entire swath of Orthodox Jewry and beyond as Rabbi Berel Wein. His hundreds of history tapes were standard listening fare for commuters, his history books were guaranteed bestsellers, the tours he led around the globe were invariably over-subscribed, some of the documentaries and animated cartoons produced by his Destiny Foundation were viewed a million times, and many hung on his weekly divrei Torah.

He was not affiliated with any organization (though he headed the OU’s Kashrus Division for years), and thus he always remained his own man, free to call balls and strikes as he saw them. That freedom allowed him, on occasion, to perform the invaluable role of communal gadfly.

He was not afraid to say, “I have no idea,” as when asked on a Headlines show for his opinion on hostage negotiations. But when he did express an opinion, it was with the confidence of being thoroughly grounded in the world of the litvishe gedolim in whose daled amos he was raised, including Rav Chaim Kreiswirth; Rav Mendel Kaplan; his maternal grandfather and boyhood hero Rav Chaim Zev Rubenstein, a product of the Volozhin yeshivah and one of the founders of Hebrew Theological College (Skokie yeshivah); and his father Rav Zev Wein, whom Rav Avraham Yitzchok HaKohein Kook once referred to as “my bookshelf” for his prodigious memory; in his own vast and near photographic command of Torah (which served him well when his eyesight failed); and his vision of the grand sweep of Jewish history.

He spoke without rhetorical flourish, in the gruff, instantly recognizable Chicago accent of his youth, just as if he were speaking to you across his dining room table. That was part of his ability to connect to so many listeners, even in large forums. And no matter what the Torah subject, much of the impact lay in his observations, asides, stories, and mussar — again, just as one would spice the conversation with a breakfast guest. One young man wrote to the Destiny Foundation upon Rabbi Wein’s passing, identifying a series of comments that had proven life-changing for him.

He enjoyed enlightening his audiences that not everything that is de rigueur today was ever thus. When he was sitting shivah for his beloved rebbetzin, he mentioned offhandedly how he had sat next to the Novominsker Rebbetzin in the only religious elementary school in Chicago in those days.

On a more serious note, he once told me that the Torah world has undergone many changes in order to preserve its core values. Both chassidus and mussar, for instance, can be seen as mutations, in his words, in response to deep-seated communal needs. And as such, both had done much to preserve the vibrancy of Torah life.

NO ONE MAN could have done so much, achieved so much, unless driven by a strong sense of mission. That mission was that with which the Chofetz Chaim charged Rabbi Wein’s father-in-law, Rav Eliezer Levin of Detroit, as the latter prepared to leave Europe for America: Speak to Jews. For Rabbi Wein, that meant make them proud of being part of the Jewish People; provide them with a framework for viewing the present in the context not only of the past, but of the future; show them the Divine Providence that has always guided our people, even when it was obscure; and above all, make them feel that they, too, have a unique role to play in making that history and are not just bystanders.

He had an almost insatiable desire to teach. On an average Shabbos in Monsey, he would give six or seven shiurim and drashos. In every community in which he served as a rav, he also taught — in Rabbi Sender Gross’s Hebrew Academy in Miami; as rosh yeshivah of Shaarei Torah in Monsey; at Ohr Somayach in Yerushalayim. And those shiurim covered the full expanse of Torah.

At least twice, I heard from Rabbi Wein the story of the 1946 visit by Rav Yitzchak Isaac HaLevi Herzog, the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Israel, to Chicago. It was clear from the way he told the story that it was not just an interesting memory but served as ner l’raglo for the rest of his life. He related the excitement of being taken early in the morning by his father to greet Rav Herzog on the tarmac, and of the latter’s regality as he descended from the plane, silver-tipped rabbinic cane in one hand and a Tanach in the other.

Later, Rav Herzog delivered a shiur on ein shaliach l’davar aveirah to a packed beis medrash at HTC. And then, he spoke of his reason for coming to Chicago. He had just come from a meeting with the pope, at which he had presented the pope with the names of 10,000 Jewish children whose parents had handed them over to the Church to hide during the Holocaust. Rav Herzog requested their return to the Jewish People. The pope refused. The children had been baptized and were now Catholics, he said.

When he told the story, Rav Herzog put down his head and sobbed, as the twelve-year-old Berel Wein had never heard anyone sob before or since. “It was,” he remembered, “as if 2,000 years of suffering in galus was pouring out of him.”

After regaining control of himself, Rav Herzog addressed each person present: “I can’t do any more for those children. But what are you going to do to rebuild the Jewish People?”

When the yeshivah students passed in a line to shake Rav Herzog’s hand, he asked the young Berel Wein, “Did you hear what I said?”

Nearly 80 years later, he still did.

That desire to “do for the Jewish People,” was nurtured in the Wein home. Another story that Rabbi Wein did not tire of telling involved the family Shabbos table. An immigrant rabbi arrived in Chicago after the war, without a piece of furniture. Rabbi Wein’s mother pointed out that their own family was only three people, and they could give away their large table and eat their Shabbos meals on the kitchen table, which they did for years.

That readiness to give away the family’s most expensive piece of furniture to a family in need captured for Rabbi Wein the lack of materialism of the litvishe Jews among whom he grew up and how they never lost themselves in the pursuit of money. But more than that, it was a lesson in how far one must go to help a fellow Jew.

As a 15-year-old, in the shiur of Rav Mendel Kaplan, newly arrived in Chicago from Shanghai, Rabbi Wein understood quickly that nothing that Rav Mendel said could be taken “only at face value.” Rav Mendel was always working on multiple levels.

But one thing he did understand clearly was the need to love every Jew and to always see the good in them. “I don’t remember him ever saying anything negative about any Jew. He used to say, ‘You can’t truly estimate what a Jew is, no matter what kind of Jew,” Rabbi Wein wrote in his introduction to the biography of Rav Mendel Kaplan.

As a consequence, he wrote, “all of his students make very poor haters. It was very hard to be a hater if you were around him for any period of time.”

When David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister, came to Chicago to raise money for Israel Bonds, Rav Mendel went to the gathering in his honor and stood at the back of the ornate room of the Palmer House observing Jews lining up to purchase the bonds. Later, Rav Mendel told his shiur, “That’s the Jewish People. That’s the children of Avraham — they have such a love of doing kindness that they’ll stand in line to give away their money.”

That same attitude of always looking for the good in every Jew remained with Rabbi Wein his entire life, which explains why he was perhaps the only black-hatted rabbi to be regularly invited to address Federation groups.

HIS PASSING also represents a personal loss for me. I recently embarked on a project with a heavy focus on Chicago Jewish history. One of the attractions in my mind was that it would afford an opportunity to spend many hours with Rabbi Wein, the greatest repository of that history. But my loss only makes me one of the tens of thousands left bereft by the passing of an irreplaceable figure, whose like we will not see again.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1075)

Oops! We could not locate your form.