The Giant from Grodno

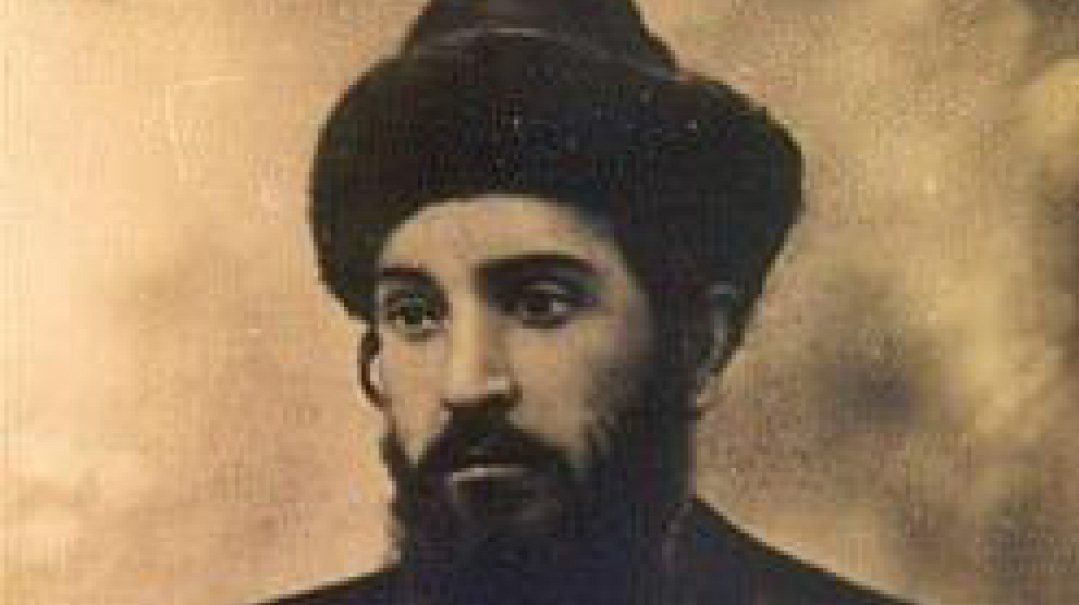

| August 30, 2022The rabbinical career of Rav Margolios (1847–1935) spanned more than six decades and traversed the fault lines of Jewish communal life on both sides of the Atlantic

Title: The Giant from Grodno

Location: New York, NY

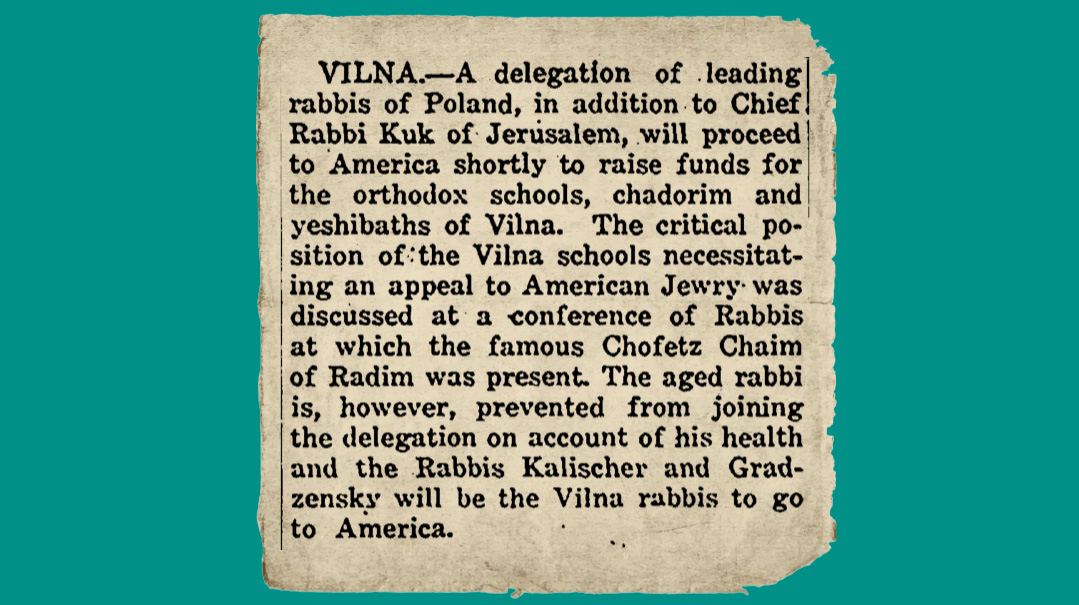

Document: The Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle

Time: February 8, 1907

American Orthodoxy’s rich history includes various rabbinic groups. The most well known were the Agudath Harabonim, Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America (OU), and the Rabbinical Council of America (RCA). A much-less-heralded group called the Knesseth Harabonim, co-founded by Rav Gavriel Zev Margolios, staked out American Orthodoxy’s right flank, and would fight to uphold kashrus standards amid early-20th-century shechitah scandals and later controversies during Prohibition.

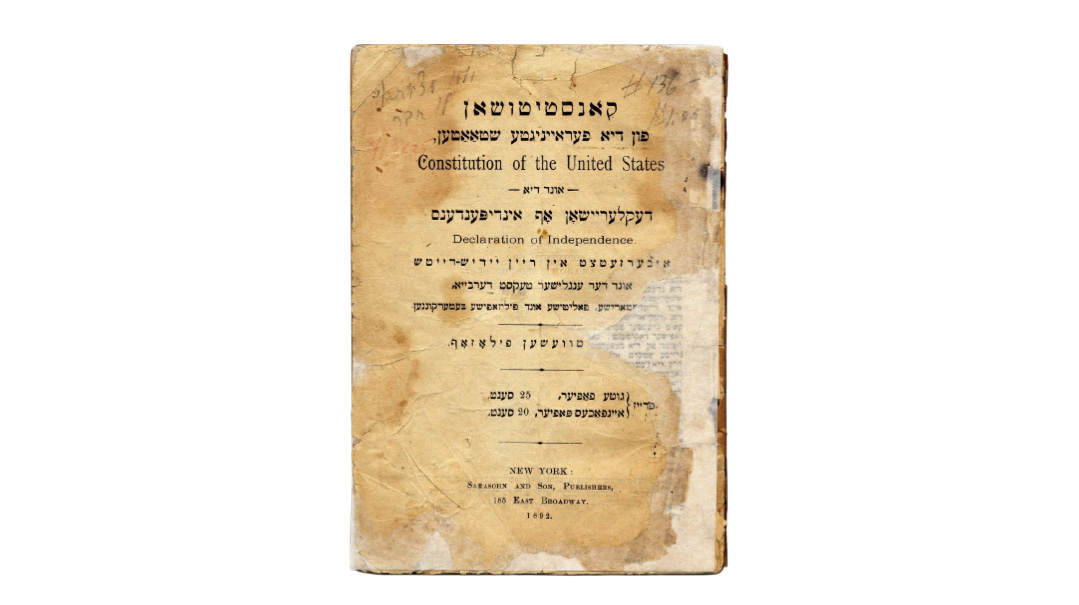

The rabbinical career of Rav Margolios (1847–1935) spanned more than six decades and traversed the fault lines of Jewish communal life on both sides of the Atlantic. Born into a prominent Vilna family, he studied under Rav Yaakov Barit of Vilna and the Netziv in Volozhin, receiving semichah from both. He then worked with Rav Eizele Charif to publish a commentary on the Jerusalem Talmud, titled Noam Yerushalmi. Following his marriage to Rivka Kaplan, daughter of the saintly Rav Nochumke of Horodna (Grodno), he served in a succession of rabbinical positions before being appointed to the Grodno rabbinate, where he’d remain for 27 years.

“Rav Velvele,” as he was known, was deeply concerned over European Jewry’s downward spiritual trajectory, and got involved in a variety of efforts aimed at righting the ship. Initially a supporter of both Chovevei Zion and later the Zionist movement, he attended the second Zionist Congress in Basel. He soon reconsidered his earlier support and emerged as one of the most vociferous opponents of the nationalist movement. Disillusioned with the direction Jewish life had taken in the czar’s Pale of Settlement, he sought to emigrate to the United States, where he envisioned establishing a traditional communal infrastructure along the lines of Russia’s before the mid 19th century.

In 1907 Rav Margolios accepted an invitation to serve as rabbi of an association of Orthodox synagogues in Boston, and he embarked on implementing his vision of American Orthodoxy. He prioritized reforming the chaotic kashrus supervision, encouraging Shabbos observance, and improving Jewish education. He quickly realized that the traditional kehillah structure was not going to work in Boston.

Seeking a larger challenge, Rav Margolios moved to New York City in 1911 to take the helm of the Lower East Side’s Adath Israel. His leadership of the Adath Israel synagogue presaged his influence on the Jewish national scene. In 1924, an observer noted, “By a provision in the constitution of the synagogue, all members pay the same fee for the support of the synagogue and no member is permitted to pay one cent more. The result is that the absolute dominion of Rav Velvele is unquestioned, as no member however wealthy or however influential has a whit more say in the management of the congregation than the humblest person.”

Rav Margolios’s attempts at imposing order and kashrus supervision on the poultry and meat markets led him into direct confrontation with the shochtim, the unions, and the establishment rabbis of the Agudath Harabonim. Following years of controversy, in 1920, he joined with Kansas City’s Rabbi Shimon Glazer and founded the Knesseth Harabonim (he felt that the term Agudah, meaning “union,” had a business connotation).

While several public relations wars broke out between the rival groups in the 1920s, they managed occasionally to put their differences aside to cooperate on social issues of the day that affected Jews, the improvement of rabbinical life, and assistance to persecuted Jews across the world. Eventually the Knesseth Harabonim fizzled out in the 1940s.

Hail to All the Chiefs

An apocryphal tale circulated about the plethora of “chief rabbis” who established themselves in New York City during the early 20th century. One figure — who posted a large sign outside his home declaring him as such — was asked who had appointed him to the distinguished position. Not batting an eyelash, the rabbi replied, “The sign painter!”

A Prolific Pen

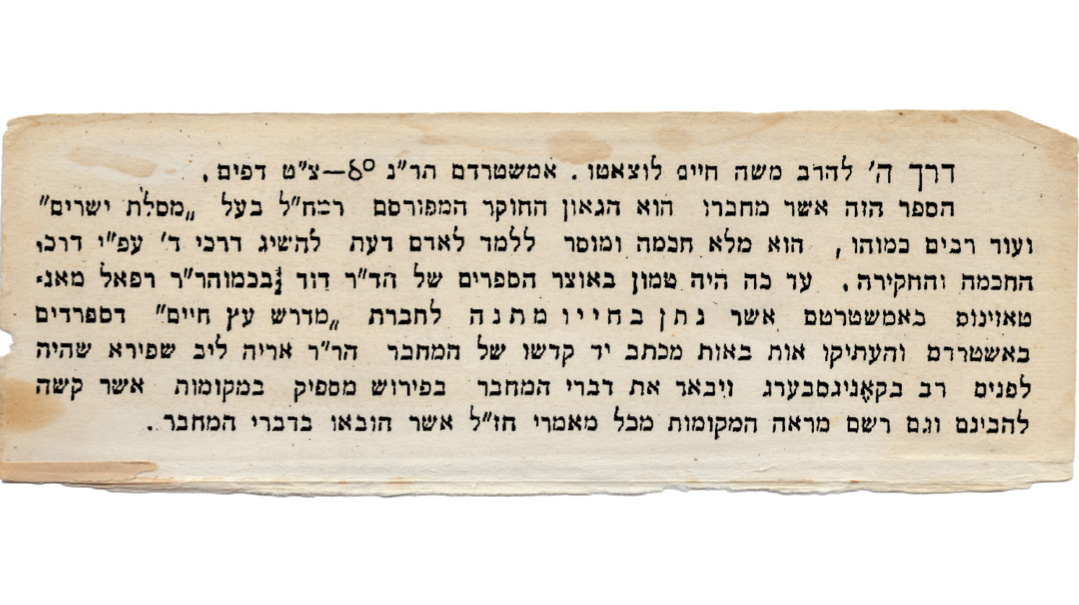

Rav Velvele authored a number of works, including Sheim Olam; Toras Gavriel (five volumes); Agudas Ezov (1924); Ginzei Margolios Shir Hashirim v’Rus (1921); and Ginzei Margolios Koheles v’Eichah (1925). When Adath Israel was refurbished in the early 1950s, a shed in the back that housed Rav Velvele’s writings was cleared out, and its contents, most of which were water-logged, were buried or discarded. What survived constitutes a valuable contribution to Torah commentary and responsa, and gives insight into both his worldview and his attempts to implement it, as seen in the decade’s worth of polemics he engaged in with many adversaries.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 926)

Oops! We could not locate your form.