The Final Aria

| June 13, 2023Legendary chazzan Yossele Rosenblatt had always dreamed that his last pulpit would be in the Holy Land

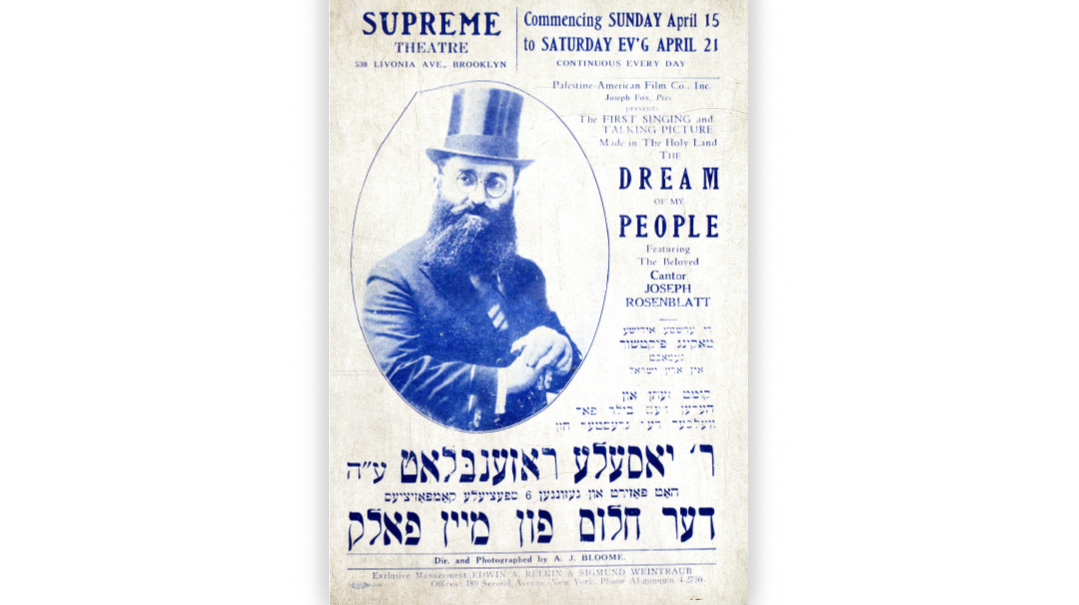

Yossele sings at the Kosel in a scene from The Dream of My People

Title: The Final Aria

Location: Yerushalayim

Document: “The Dream of My People”

Time: 1933

He had no sooner landed on its shore than it seemed to him as though an oppressive weight had been lifted from him. He felt rejuvenated, restored, filled with new hope and zest for living. The first piano he saw was immediately put into action by him, and, after having played on it for a while in an accompaniment of a tune he was singing, he pranced around the room like a child, so that my mother felt embarrassed.

“Yossele, what are you doing?” she tried to interrupt his frolicking. “You are behaving like an infant.”

“That’s exactly how I feel — like a newborn babe,” was my father’s quick retort.

—Biography of Yossele Rosenblatt by his son Rabbi Samuel Rosenblatt

Legendary chazzan Yossele Rosenblatt had always dreamed that his last pulpit would be in the Holy Land. He thought about possible settlement there at the beginning of 1933, when his financial situation had reached a critical stage.

“I am tired of the hustle and bustle of America and of American Jewry,” he confided to a friend. “I have no complaints against America, mind you, or against American Jews. They have lavished upon me riches and honor. Nevertheless, America robbed me of something inside that I will never be able to find again.”

He was referring to that peace of mind of he had been denied the preceding ten years. He was very envious of his colleague Zavel Kwartin for having left the United States and settled in the Land of Israel.

“He is a smart man, this fellow Kwartin,” he used to say. “And I am a fool. But no matter, I’ll go to the Land of Israel also. You will see.”

An opportunity to realize his lifelong ambition presented itself when Joseph Fox, general manager of the Kol-Or Palestine American production company, invited him to take the leading role in a film to be shot in the Holy Land. His role was to chant some of his own famous compositions at various holy sites across the land.

As with many of the ventures Yossele Rosenblatt undertook, the film’s financial risks were obvious and the chances of success were doubtful at best. While he was blessed with a wide vocal range and abundant musical talent, his lack of business acumen and extreme generosity had already brought him to the brink of bankruptcy. Yet despite receiving only promises of the project’s profit potential, he seized the opportunity to perform for a filmed concert tour in Eretz Yisrael.

The project had both a pull and a push for Rosenblatt. With no end in sight to the Great Depression, his economic prospects in the United States looked bleak. Paradoxically, the Holy Land was on the cusp of a boom, with the Jewish population receiving an infusion from the Fifth Aliyah and an influx of wealthy refugees from Germany, where Hitler had just assumed power.

Then there was the issue of the Rosenblatts’ extensive debts. Numerous creditors pursued him and some even attempted to prevent his trip to Palestine. Yossele and his wife Taubele set sail on the Italian liner Vulcania on March 24, 1933, taking along their son Henry but leaving the other seven children behind in New York, arriving in Haifa in time for Pesach.

Yossele knew how to please diverse crowds. On the first day of Pesach, he performed in Ohel Shem, the largest auditorium in Tel Aviv, and on the last day in Yeshivas Meah Shearim. Yossele sang in Meron on Lag B’omer; officiated on Shabbos in Rishon L’Tzion and on Shavuos in the Great Synagogue in Tel Aviv; gave a concert in Kibbutz Ein Charod, and a recital in Beit Ha’am in Tel Aviv. He also served as chazzan at the shul and tish of the Sadigura Rebbe in Tzfas, just as he had more than four decades earlier in the presence of the Rebbe’s grandfather in Sadigura.

Cantor Rosenblatt took up residence at Jerusalem’s Hotel Amdursky for most of his ten-week stay. During this time he often spent Shabbos afternoons at the home of Chief Rabbi Rav Avraham Yitzchak Kook, forming a close relationship with him. The lucrative concerts and engagements more than covered his expenses and even paid off most of his debts. In order to solidify his financial position, he planned an extensive European tour, and had already purchased tickets for a ship to Romania. He also hoped that the Palestine film would provide him with additional financial security.

As he prepared for what he hoped would be a temporary hiatus from the Holy Land, on the last Shabbos of his stay Rosenblatt conducted a farewell service in the Old City’s Churvah Shul . Neither he nor anyone else present had any idea that it was indeed a farewell service —not only to the Land of Israel but to This World. The Land would become his everlasting home.

“Angels must have helped him make that music,” Rav Kook remarked when he recalled that Shabbos.

Yossele appeared to be floating on air. His chanting was so inspired that those in attendance applauded several times, and then lifted him up on their shoulders and carried him in triumph through the narrow lanes of the Old City.

The next morning he left for the Jordan River and Dead Sea to complete his work on the film The Dream of My People. At Kever Rachel, he sang “‘Kol b’ramah nishma, Rachel mevakah al baneha,” and to those who heard him it almost seemed that Rachel Imeinu herself was crying for her children. Following singing at Mearas Hamachpeilah in Chevron, Yossele and his crew proceeded to the Jordan River. There he stood in a dinghy and lifted his melodious voice in his fast-moving “B’tzeis Yisrael.” He was excited at the opportunity to chant one of his favorite melodies in its natural surroundings.

The next part of the picture called for him to bathe in the thick, salty waters of the Dead Sea. It was a stiflingly hot day, and he began to complain of pressure near his stomach. He was in considerable pain when he was brought back to his Jerusalem hotel. A doctor was summoned who prescribed rest. A few hours later, while his wife anxiously watched over him, he passed away.

The sudden passing of the world’s most famous cantor was reported worldwide in both the Jewish and general press. More than 5,000 attended his funeral the next day, where he was buried on Har Hazeisim. Hespedim were delivered by Rav Kook and other dignitaries, while the burial prayers were chanted by his two colleagues Zawel Kwartin and Mordechai Hershman.

Moved by the Titanic

Yossele Rosenblatt’s sublime voice was exceeded only by his unparalleled generosity. His wife often needed to protect their savings from his instinct to give it all away. As fate would have it, his move from Europe to America coincided with the tragic sinking of the Titanic in 1912, a calamity that deeply affected his wife.

Yossele followed through with his planned journey to New York, encouraged by an invitation from the First Hungarian Congregation Ohab Zedek. The legendary chazzan would make the city his permanent home. The Titanic disaster, along with the death of the esteemed Jewish philanthropist Isidor Strauss, moved Rosenblatt profoundly. He channeled his sorrow into a haunting rendition of Keil Malei Rachamim, recorded with RCA Victor Records. This beautiful recording was a commercial success, and Rosenblatt, true to his generous nature, donated all $150,000 in proceeds to the families of the Titanic victims, offering them a beacon of hope amid their despair.

The Making of a Gadol

On the Shabbos destined to be his last, Jerusalem hummed in anticipation of Yossele’s forthcoming performance at the Churvah Shul. Caught up in the fervor was a 23-year-old masmid, recently married, who devoted himself entirely to Torah study at Meah Shearim’s Tiferes Bochurim shul.

Like many great Torah scholars, he appreciated a splendid davening, and the prospect of hearing the world-class chazzan appealed greatly to him, despite the potential disruption to his stringent learning routine. As he merged with the crowds headed for the Old City, he pondered, “Am really going to sacrifice my Torah learning to go hear a great chazzan?” Abruptly, he turned around and headed back to the beis medrash and his cherished Gemara.

Many years later, he recounted to his grandson, “Imagine the sechar I received for resisting the once-in-a-lifetime chance to hear the esteemed Yossele Rosenblatt.”

That young man was none other than the future gadol hador, Rav Yosef Shalom Elyashiv, whose eternal melody of Torah still resonates.

This Wednesday, the 25th of Sivan, marks the 90th yahrtzeit of Chazzan Yossele Rosenblatt

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 965)

Oops! We could not locate your form.