The Fear Factor

What's really motivating voters this election season? A voter psychology story

When people wax nostalgic for a Hubert Humphrey-style Democrat, political scientist Herb Weisberg can’t help but empathize.

Weisberg grew up in the Minneapolis of the 1940s, where Jews and blacks lived in adjoining sections of the city’s Near North neighborhood. At Ohio State University, he devoted his adult life to analyzing how American Jews vote, but can never forget the religious and racial discrimination that was a fact of life for both Jews and blacks in Minneapolis.

“I had two uncles who got degrees in engineering at the University of Minnesota and couldn’t get jobs in the city because they were Jewish,” said Weisberg in a recent telephone interview. To confirm that, he suggested I look for an article, written by Carey McWilliams in 1946 for the monthly magazine Common Ground, which called out Minneapolis as the capital of anti-Semitism in the United States.

It took a fair-minded mayor named Hubert Humphrey to forge a new social contract for the city. Back then, the Lutheran church was a powerful force, so Mayor Humphrey reached out to Pastor Reuben Youngdahl in 1947 to head his Committee on Human Relations.

Minneapolis soon turned over a new leaf. The city passed anti-discrimination laws that opened up innovative employment and housing opportunities for minorities. Humphrey gained national prominence as a progressive reformer. Minnesotans elected him to the US senate in 1948, Lyndon Johnson tabbed Humphrey as his vice president when Johnson became president after JFK was assassinated, and Humphrey just missed becoming president when Richard Nixon defeated him in 1968 by a razor-thin margin of 0.6%.

That was then. This is now.

Minneapolis is once again a national tinderbox of race relations after a white police officer stands accused of murdering a black man, George Floyd. Moderate Hubert Humphrey Democrats are facing extinction in a political world where the term “progressive” has taken on an entirely new meaning. Racism and anti-Semitism are back and out in the open. Polarization — once a concept schoolchildren learned playing with magnets in science class — exerts a negative force on the political system. Public office holders, more than ever, play divide and conquer with the raw emotions of voters to gain a winning edge.

“Scientific research shows people vote with their gut, not with their heads. Elections are won and lost on anger, fear, hatred and rage,” says Dr. Erez Yaakobi, who has worked behind the scenes on analytics for several political campaigns, and on quieter days, is a senior lecturer at Ono Academic College in Tel Aviv. His latest book, Killer Instinct, soon to be published in English, succinctly conveys the predatory nature of today’s triumphant politician. “In the US, and elsewhere, candidates are fueling divisions. Politicians believe that if they strategically divide people into “us” and “them,” and continue to speak this language and frame the debate this way, they will win.”

Gut Feelings and the Vote

So if voters can no longer select candidates based on their stances on the issues, and if there is only one remaining political ideology, and that’s to tear down the existing order, on what basis are we making our voting decisions? And how often are they the right ones for us?

Professor David Redlawsk, who chairs the political science department at the University of Delaware, coined the term “correct voting” to evaluate the quality of voter decision-making. Redlawsk, a political psychologist, studies voter behavior and emotion and how voters process political information to make their decisions. His measuring rod is the extent to which people vote in accordance with their own values and priorities.

“Democracy works best when citizens are interested in politics, able to place current events in proper historical context, attentive to the actions of representatives in government, aware of institutional rules and requirements so that responsibility for government actions can be properly attributed, and engaged in the governing process to the extent they vote for the candidates they believe best represent their interests,” wrote Redlawsk, before concluding: “This is a pretty tall order, one that few citizens come anywhere close to filling.”

Instead, he says, we end up relying on different cognitive shortcuts, or heuristics, in professional parlance, to help us tame the information overload and make our best decisions.

Redlawsk first developed this theory in the mid-1990s, so I called him to bring us up to date.

“Our traditional measure of correct voting still means finding and voting for the candidate who best represents your policy interests. But it’s a relative measure,” Redlawsk says. “A correct vote, say, for Donald Trump only means Trump is closer to you on the issues you care about. Trump doesn’t have to perfect for you, he just has to be better than Biden.”

Sometimes the equation is even simpler.

“There is also the emotional heuristic — the idea of a deep feeling that gets us out of the cognitive world we live in. A great example is political partisanship. There are two parties. You know what Democrats and Republicans stand for. So you merely have to match that to your own preferences. Then it becomes a really simple calculation. You go with your gut feeling because you know you hate the other guys so you don’t really need any more information, you just vote against them.”

Demagogic Democracy

Unfortunate as this may sound to those who prefer issues-oriented politics, substance over style, and results over rhetoric, today politicians of all stripes run against the existing political order and create disorder once they take command.

In some respects, these newcomers are a reflection of the contemporary voting public. Citizens worldwide are fed up with their governments, which they view as corrupt and self-serving. The world is awash in wealth — just look at the stock market — but little of that trickles down to working families in the form of financial security. Housing gets more unaffordable by the year and personal safety and security can no longer be taken for granted, even in the quietest suburban communities.

The political order that’s run much of the world since the end of the World War II is in decline and demagoguery is on the rise. Authoritarian leaders of Russia, China, and Turkey subvert the few liberties their people have and cement their own personal power for decades to come. In the US and Europe, political scientists of all stripes — liberal and conservative, pro-Trump and anti-Trump — agree that there is little difference in style between the campaigns that elevated Donald Trump to the presidency; the never-ending campaigns that keep Binyamin Netanyahu in power; Britain’s Brexit campaign; and the rise of populist parties in France, Hungary, Poland, Italy, and Austria and elsewhere.

Trump ran against Washington, D.C., and promised to drain the swamp. Netanyahu ran against the “state of Tel Aviv,” code language for the country’s liberal elite. Boris Johnson’s British accent bestows him with a slightly more elegant lilt but he too is a disruptor of the highest order.

Voters do expect politicians, with the outsized power they wield, to improve their lives by fixing what’s broken, and to tell us as much as we need to know without scaring us by telling everything they know. Yet, considering how candidates for public office rarely tell the whole truth and flip-flop on issues after taking office (the view from here isn’t the same as the view was from there) and often drop their agenda to deal with unanticipated traumas (9-11 and COVID-19), voters never know in advance who will rise to the occasion and who will flop.

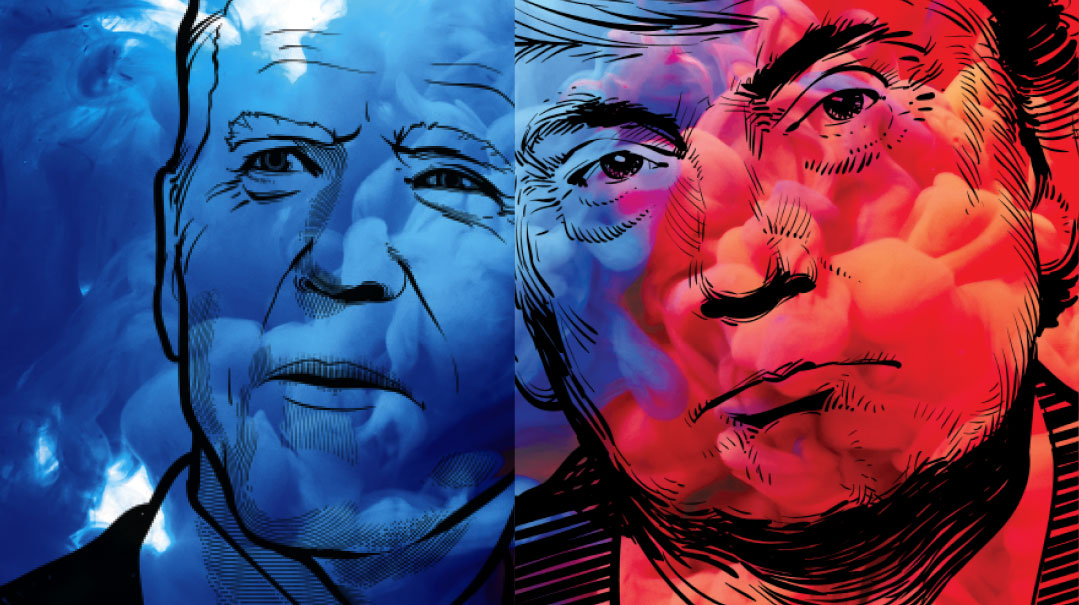

Trump’s Identity Festivals

This year’s election, plain and simple, is a referendum on Donald Trump. The American people have a passionate love-hate relationship with the president, and most voters have already made up their minds — although several political psychologists I interviewed and follow have divergent views on Trump’s campaign strategy and whether he caters to people’s best, or worst, instincts, or a combination of both.

For Dr. Yaakobi, Trump has a suitable brand of killer instinct, which he defines as doing almost anything to achieve goals. “The person who has this killer instinct will be perceived as a much better candidate than his opponent. Donald Trump has it. He does what he believes is correct and good for the American people. If he thinks a nuclear agreement is not good, he cancels it. If he thinks now is a good time to speak to the leader of a certain country he will do it. The base of the Republicans perceive that his actions are correct, that he’s the leader and we will follow our leader,” Dr. Yaakobi says.

Strong confirmation of that can be found in an article in the Scientific American written shortly before Trump’s 2016 victory. Authors Stephen Reicher and S. Alexander Haslam noted what they called the “unprecedented assault on the candidate and his supporters, which went so far as to question their very grasp on reality.”

While agreeing that Trump drew support from white supremacists, and others who were prepared to live with racist statements about Muslims, Mexicans, and others, Reicher and Haslam contended that racism, bigotry, and bias were “certainly not” the main reasons people supported Trump.

Rejecting the prevailing view in the media that Trump rallies are an assemblage of a mindless mob motivated by primitive urges and stirred up by a narcissistic demagogue, they argue that Trump embraced a new psychology of leadership and lauded his skills as a collective “sense-maker” — someone who both shaped and responded to the perspective of his audience.

“In simple terms,” wrote Reicher and Haslam, “a Trump rally was a dramatic enactment of a particular vision of America. More particularly, it enacted how Trump and his followers would like America to be. In a phrase, it was an identity festival that embodied a politics of hope.”

Not everyone sees it that way. While praising Reicher and Haslam’s analysis as insightful, Thomas Pettigrew, a professor in the department of psychology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, ticked off five negative psychological traits that he says fit Trump supporters: authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, prejudice, relative deprivation, and lack of intergroup contact. “Though found among left-wingers, authoritarianism is more numerous among right-wingers throughout the world,” wrote Pettigrew.

In email correspondence with Professor Pettigrew, he wrote that all five of these psychological tactics Trump employed in 2016 are “still in play big time” in 2020.

“He broke all the unwritten rules of American politics in 2016 and thinks he can win with them in 2020 without noting that the situation of the nation has drastically changed in the intervening years,” Pettigrew says.

Pettigrew admits that many of these tactics did not begin with Trump. In his 2017 article entitled “Social Psychological Perspectives on Trump Supporters” published in the Journal of Social and Political Psychology, Pettigrew wrote that Republicans began averaging higher on authoritarianism than Democrats before the rise of Trump and the Republican party has learned how to appeal to this segment of the American electorate in various ways.

However, in the same article, he also debunked the oft-repeated claim in the media that the average Trump voter was an angry, working-class person who was economically disenfranchised and often unemployed. Pettigrew said the median average annual income of a Trump supporter is close to $82,000 — or $5,000 more than a voter who held an unfavorable view of Trump. Having said that, he noted that social psychologists stress the importance of relative deprivation and that what voters think is true is more important in elections than the actual truth: “Trump adherents feel deprived relative to what they expected to possess at this point in their lives and relative to what they erroneously perceive other ‘less deserving’ groups have acquired. Trump exploited this sense of relative deprivation brilliantly,” says Pettigrew, whose soon-to-be-published book, Contextual Social Psychology: Reanalyzing Prejudice, Voting, and Intergroup Contact details how Trump’s 2016 victory directly mirrors the support for Brexit in the UK and reactionary parties throughout Europe.

Economic Insecurity

White Trump supporters are not the only ones who play the comparison game or who vote out of a sense of self-preservation.

“Even though before the pandemic the economy was functioning well and black unemployment was low, relative to whites, it was still pretty high. These are things black voters look at. It’s not just how well off the black community is but how well off it is relative to other types of communities,” said Dr. Darren Davis, a professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame, who specializes in research to identify the social and psychological motivations underlying political attitudes and behavior.

“The things that unfortunately motivate white voters also motivate black voters as well. White voters felt threatened and this is why I feel Trump won in 2016,” Dr. Davis says, although he contends Trump has hit his ceiling. “I don’t think there’s much more Trump can do or say, especially among voters in the middle, where there are promises that he hasn’t delivered on. Also, in 2016, the African-American voter was not motivated. They weren’t crazy about Hillary. The 2016 election will go down in history as an example of what happens when black voters aren’t engaged,” Dr. Davis said, adding that former President Obama’s endorsement of Joe Biden will play a major factor.

“Endorsements still matter in the African-American community because they serve as heuristics, shortcuts. People often criticize African-Americans for the allegiance to the Democratic Party, but what they don’t always realize is that the Democratic Party is a label, Barack Obama is a label, and this sort of endorsement and branding is critically important to the African-American voter.”

Fears of economic insecurity will also be a motivating factor in the women’s vote, as women are often driven to the polls by kitchen-table economic issues, says Debbie Walsh, director of the Center for American Women and Politics, a unit of the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers University: “Women want to see a more expansive government playing a role in their economic lives. Women voters are more sensitive about having less money for retirement and are generally more employment insecure. The social safety net is very important, such as Medicare or Medicaid, unemployment insurance, and paid family leave. All these are things that women imagine themselves needing at some point in their lives. Access to affordable health care is also factored into that now. The notion that in America, you’re one catastrophic illness away from bankruptcy is driving the women’s vote.”

Ms. Walsh contends that Trump is losing ground compared to 2016 with working-class white women and among white suburban women due to a number of factors, including his caustic personality, his rough discourse, and the way he talks about women. “His bullying on social media has not worn well with women,” she added.

The Changing Jewish Vote

If there is one voting group that President Trump can count on in November, it is chareidi Jewry. And it can be said that what’s motivating them is fear.

Polling that zooms in on the Orthodox Jewish community is still scant compared to the broader Jewish vote, which has been surveyed for decades, but an online poll conducted toward the end of January 2020 by Nishma Research and published by the Berman Jewish Databank, a project of the Jewish Federations of North America, shows a divide between chareidi and Modern Orthodox voters. In 2016, Trump beat Clinton by 36% among chareidi voters, while Clinton defeated Trump by about 27% among the Modern Orthodox.

The Nishma poll was taken before the Democratic Party primaries got underway, but looking ahead to 2020, some 73% of the chareidi public favored Trump compared to 41% among the Modern Orthodox. Overall, Trump won just 29% of the Jewish vote in 2016 and Democrats captured 79% of the Jewish vote in the 2018 midterm elections.

While Trump is clearly perceived as a greater benefactor to Israel than any of his predecessors, and Biden can be expected to roll the clock back to the Obama era policies, Israel might not be the paramount consideration of Jewish voters this year.

“There is no polling organization that’s targeting Orthodox Jews and providing real-time data, so these are just educated guesses, but for the very first time, in the Orthodox Jewish mind, Israel might be perceived as stronger than America,” says Zev Eleff, who wears many hats as an associate professor of Jewish history at Touro College, vice provost of the newly-launched Touro College Illinois, and chief academic officer of the Hebrew Theological College in Skokie. “If an Orthodox Jew used to go to the voting booth from 1948 to 2016 saying my vote is an agency to support the cause of Israel, this year, he may say I now need to think about myself and indigenous politics. I need to think about whether I have a job or not, or whether my kids can go to school in the fall, so it could be that the Orthodox Jewish voter will turn to the candidate who they feel is going to get them through the next year with more success.”

Are American Orthodox Jews frightened at the prospect of a Democratic candidate either pushing — or pushed by — a progressive agenda?

“Are the Orthodox are going to interpret the rise of anti-Semitism as part of the Black Lives Matter movement, and therefore part of a liberal agenda, or are they going to give it a right-wing stamp? I don’t know the answer right now, but historically, it’s absolutely been the case that both the radical right and the radical left are pushing anti-Semitism,” Eleff said. “It’s not for me to pass judgment on how people vote, but the reduction of political considerations to a single issue is insufficiently broad. What’s happening now, and it’s not a good thing, is that the rise of anti-Semitism and the economic collapse, along with the precarious finances of the federal government and health care, have forced all of us to broaden our thinking of what we need in a chief executive.”

The New Jewish Libertarian

Even if it isn’t perceived as a single-issue, anti-Semitism will be a major consideration for the secular Jewish voter this year.

“It’s the new issue polarizing Jewish voters, both from the left and the right,” says Professor Herbert Weisberg, an emeritus professor of political science at Ohio State University, a former coeditor of the American Journal of Political Science and author of the 2019 book: The Politics of American Jews.

Weisberg’s focus on regression analysis (the examination of the relationship between two variables) keeps him busy sifting through polls asking Jews how bad they think anti-Semitism is in the US along with their opinions about President Trump. Professor Weisberg says that in 2012 and 2013, the major pollsters of Jewish issues, be it the American Jewish Committee, the Pew Survey, or the Public Religion Research Institute, either didn’t ask that question, or if it came up, it wasn’t statistically significant.

That’s changed.

“Every poll I’ve seen taken since 2017 that asked a question about anti-Semitism shows it to be a significant factor and shows a significant correlation in how they view President Trump. The more seriously they view anti-Semitism, the more negative they are about President Trump,” Weisberg says. “Some of these polls might have a political agenda of their own and the survey questions were not ideal — not all of them were worded in a neutral way, but for the November election, the question is to what extent Jews today view anti-Semitism as more serious if it comes from the right, rather than the left, compared to how they saw it a year ago.”

During our interview, Professor Weisberg referenced a Jewish Electorate Institute 2019 survey, since updated in February 2020. That poll found some 45% of likely Jewish voters believe President Trump’s emboldening of far-right extremists and white nationalists was most concerning to them, up from 38% in 2019. Some 26% said Democrats who tolerate anti-Semitism was their greatest concern, down from 27% in 2019.

Having said that and considering his early personal family experience with anti-Semitism growing up in Minneapolis, Weisberg himself is not the slightest bit dismissive of anti-Semitism from the left.

“Until the 2018 congressional election, anti-Semitism on the right seemed to be the issue. Then came ‘the squad,’ which includes Congresswoman Ilhan Omar, who happens to be from my home district in Minneapolis,” Weisberg says. “A year ago Trump was courting the Jewish vote saying that they would be disloyal [to the Jewish people and Israel if they did not vote for him. In doing so, he was trying to make anti-Semitism from the left more evident, whether it was pointing out Rep. Omar’s tweets or anti-Semitic events on US campuses where it had become unsafe for Jewish students on campus to support Israel.”

Certainly among America’s Orthodox Jews, a primary fear propelling support for Trump is the rise of the progressive left. Many Orthodox Jews are pessimistic about the future of their cities and the country as a whole should the progressive agenda be enacted, with its very real potential to transform America into a much more hostile place for Jews. They see Trump as a defender of the values they hold dear, and for them, a vote for Trump in November is the quintessential “correct vote,” according to Professor Redlawsk’s original definition of the term.

According to Weisberg, that rightward trend may not be limited to strictly Orthodox Jews. Remove Trump — with his checkered record and problematic personality — from the picture, and there’s a chance that a hybrid approach would be a better fit for many American Jews. For a while now, he’s been toying with the theory that the broader US Jewish vote is actually more conservative than the polls indicate.

“I find that as much as 25% of the Jewish vote is actually Libertarian,” he says. “Not the Rand Paul or Cato Institute-type libertarians, but Jews who are socially liberal but economically conservative, who favor smaller federal government and lower taxes.” He adds that much depends on the outcome of, and the reaction to, the 2020 vote to analyze Jewish voting patterns going forward. “If Trump is really gone in 2020, and I wouldn’t bet on that, that’s when the Jewish vote will shift, and that’s when it will move more toward the Republicans. I think Trump has deterred the Jewish vote from becoming more Republican.”

Part of that trend to a more conservative or libertarian stance could come as a reaction to whatever twists and turns the progressive movement takes.

“Whether Biden wins or loses, the Democratic progressives are not going to go away,” Weisberg says. “They are a loud voice in the Democratic Party and they’re going to get louder.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 822)

Oops! We could not locate your form.