The Eternal Flame: The Life, Travels, and Martyrdom of Rav Elchonon Wasserman

The life, travels, and martyrdom of Rav Elchonon Wasserman

Photos: ArtScroll, Mr. Shimon Glick, DMS Yeshiva Archives, National Orthodox Jewish Archives of Agudath Israel, JDC Archives, YU Archives, Kedem Auctions, Legacy Judaica and Brand Auctions

Illustration: Mikhail Chapiro/AhavArt

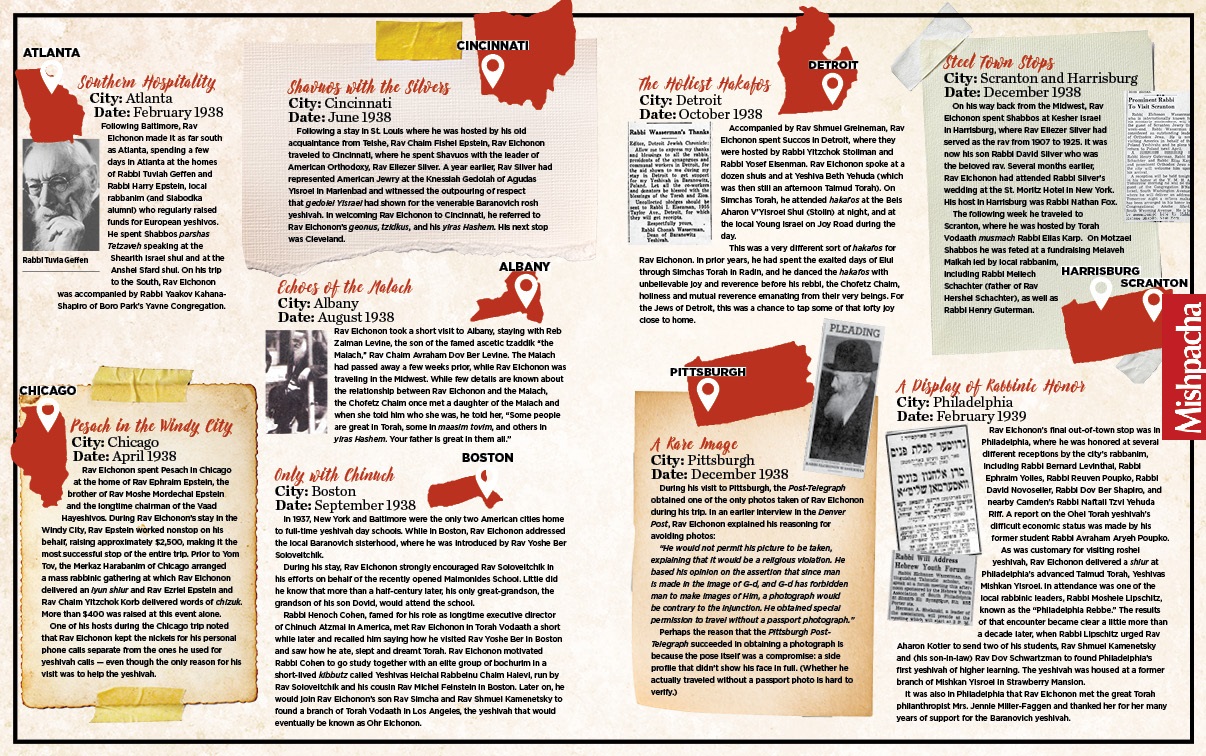

It was a bright fall Day in 1938 when Rav Elchonon Wasserman alighted from the overnight Pullman train in Denver’s Union Station. If any crowd awaited him at all, it was negligible. This suited him fine, for neither fanfare nor the healing Rocky Mountain air was what had brought him out to the great American west. The Torah leader was more than a year into a whirlwind journey across America to lift his yeshivah out of crushing debt. Though exhausted, he stood erect, refusing to allow his depleted state to affect his regal posture.

While the greater, primarily secular Denver Jewish community had little interest in “old world rabbis,” the local press had been alerted and a reporter from the Denver Post arranged a sit-down with Rav Elchonon. His traveling companion, Rav Shmuel Greineman, the menahel at Mesivta Tiferes Yerushalayim on New York’s Lower East Side, served as translator.

Most of America’s Jews did not quite recognize the epochal changes that their guest had wrought across Europe’s yeshivah world. Years earlier, Rav Elchonon had acted on the instructions of his lifelong mentor, the Chofetz Chaim, and revolutionized the concept of the modern yeshivah. In Baranovich Rav Elchonon built upon the foundations laid by Rav Chaim Volozhiner, father of the modern-day yeshivah, and brilliantly implemented the adjustments necessary for a world decimated by turmoil and increasing secularization. In Rav Elchonon’s view, lomdus — the complex analysis of textual minutiae — was important, but mastery and breadth — the consumption of vast tracts of knowledge — was to be paramount. He focused on younger bochurim, opening his yeshivah ketanah to students roughly equivalent to today’s high school boys, and the products of his yeshivah entered the great Torah centers armed with the proper learning skills and character traits to become enduring Torah scholars.

The reporter assigned to interview Rav Elchonon on that autumn day in Denver knew little about the educational revolution his subject had spearheaded. But he quickly realized that this interview was to be like none other he’d conducted. With the rabbi refusing to sit for a photo, the writer used words instead to capture him: he termed Rav Elchonon “The Jewish Einstein,” describing him as “clear-complexioned and bearded…. a remarkable prototype of the artistic conception of the Jewish patriarch.”

Rav Elchonon was uninterested in small talk. “The ‘Holy Books’ speak of these times,” he said. “It speaks of the coming of the Messiah, of the birth of a new good world, and it says that there shall be suffering and pain in that birth.

“It is impossible to predict what will happen to the world in a given space of years; history now is concentrated,” Rav Elchonon continued. “Events move rapidly. In an incredibly short time, upheaval can come, reversing conditions that seemed as permanent as a man could make them. A year today is a century of yesterday. Time is no more than an idea of man, and he must not place too much reliance on it. There is a higher conception of time.”

Just a few days later, Rav Elchonon arrived at his next stop — Dallas, Texas — and the shocking reports filtered in. November 9 and 10, 1938, are forever branded in the calendar as Kristallnacht, the night shuls, homes, and businesses across Germany and Austria were burned and destroyed, Jews beaten and even killed, as the true face of Nazi evil was unmasked for the world to see. Events were about to spin rapidly beyond anyone’s predictions. For some the news was shocking, but for Rav Elchonon it was far from a surprise.

What few would realize, however, was that the juxtaposition of events — and Rav Elchonon’s presence in America during the first rumblings of European Jewry’s impending destruction — had been orchestrated by a heavenly Hand. During the 17 months he spent traversing America, Rav Elchonon didn’t only advocate for his students back in Baranovich. He also planted seeds for the eventual flourishing of a new yeshivah world, nurtured a select group of future activists and leaders, and helped American Jewry set priorities so the coming generations would remain firmly linked to their heritage.

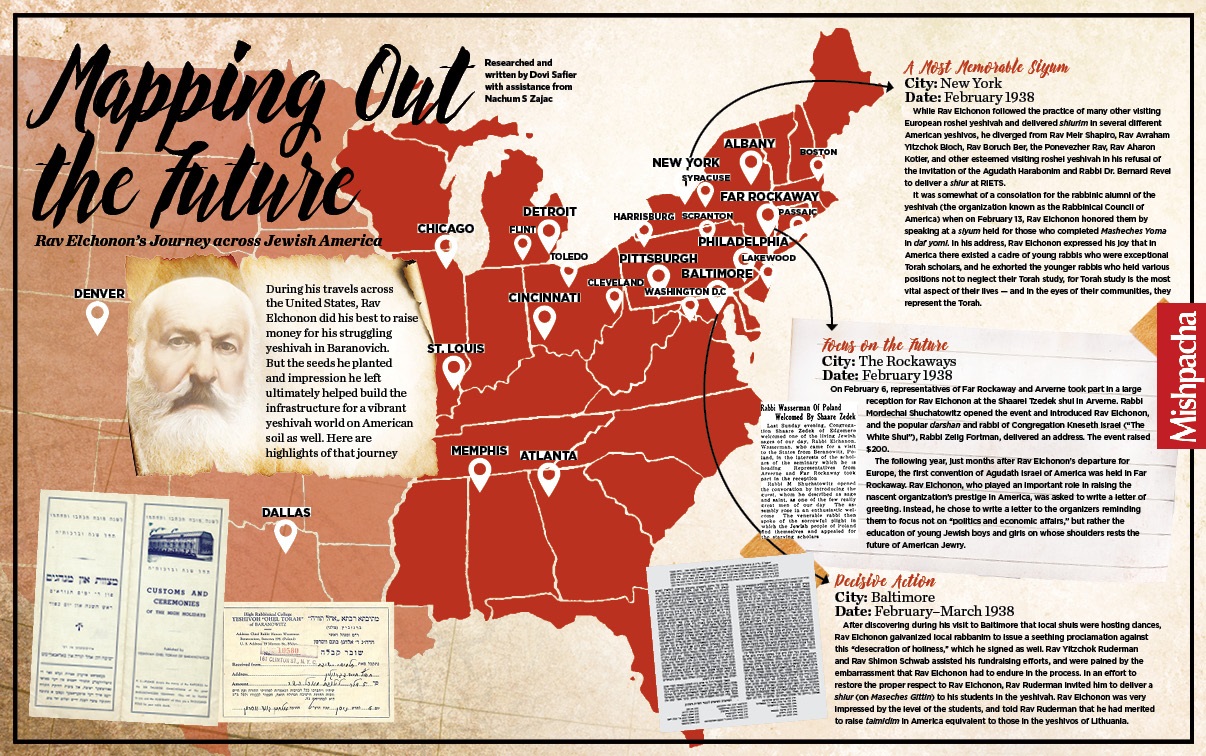

Two of Rav Elchonon’s primary rebbeim, Rav Shimon Shkop and Rav Lazer Gordon

The Chofetz Chaim’s Trustee

Elchonon Bunim Wasserman was born in Birzh (Lithuania) in 1875. His father, Nafali Beinish, was a shopkeeper with no particularly prestigious lineage, but young Elchonon quickly excelled in his Torah learning. The family moved to Boisk, and he studied at the nearby Telshe Yeshiva under Rav Eliezer Gordon and Rav Shimon Shkop. On trips back home, he studied with Rav Avraham Yitzchok Hakohen Kook, the Rav in Boisk. He later spent time studying under Rav Chaim Soloveitchik of Brisk, where he also taught in the years preceding the first World War. Rav Elchonon became deeply attached to Rav Chaim and his way of learning.

In 1898 he married Michla Atlas, the daughter of the famed scholar (and founder of the Telshe Yeshivah) Rav Meir Atlas, Av Beis Din of Salant and Shavil and father-in-law of Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski.

After a short tenure as a rosh yeshivah in Amtchislav, Belarus together with Rav Yoel Baranchik of Riga, Rav Elchonon decided to leave after the townspeople asked him to make certain compromises that he felt betrayed his principles. Leaving his wife and family behind, Rav Elchonon traveled to Radin as a porush where he joined the Chofetz Chaim’s Kollel Kodshim. There his chavrusa was another product of Telshe, the eventual Ponevezher Rav, Rav Yosef Shlomo Kahaneman. The two joined a group of Europe’s greatest Torah scholars to learn Seder Kodshim, a priority of the Chofetz Chaim as he prepared for what he felt was Mashiach’s imminent arrival.

This move would greatly alter the trajectory of his life. So intensely was Rav Elchonon influenced by the Chofetz Chaim that he felt as if he had been transformed into a new person, his rebbi’s character and conduct indelibly etched into every fiber of his being.

Even after he departed Radin, Rav Elchonon made it his tradition to return each year for Elul and the Yamim Noraim, thirsting for any contact possible with his rebbi. He absorbed every word and sought his advice on countless matters. Following one of the Chofetz Chaim’s Rosh Hashanah shmuessen, someone remarked to Rav Elchonon that the elderly Chofetz Chaim had said the exact same thing the year before. “Not quite,” replied Rav Elchonon. “This year he included eight additional words.”

Rav Elchonon’s regard for the Chofetz Chaim was hardly one-sided, for when the Chofetz Chaim prepared to leave Poland for Eretz Yisrael, a committee of gedolim came to plead with him to stay on. One asked, “Rebbi, in whose hands do you leave us?” The Chofetz Chaim replied, “I leave you with Rav Elchonon!”

Perhaps nowhere was that trust more evident than in the Ohel Torah yeshivah of Baranovich. The Alter of Novardok, Rav Yosef Yoizel Horowitz, opened the Ohel Torah Yeshivah, a branch of the Novardok yeshivah network, in Baranovich in 1907-8. This relatively new town had developed over the previous few decades due to its position as a central railway junction. The first rav of the town was Rav Chaim Leib Lubchansky, whose son Rav Yisroel Yaakov married the Alter’s daughter. Rav Lubchansky assumed control of the new Novardok branch in town, together with the assistance of a local individual named Rav Chaikel Sofer. Another son-in-law of the Alter, Rav Avraham Yafen, served as a maggid shiur and would later lead the entire Novardok yeshivah network.

During the First World War, with Baranovich on the front lines and later under German occupation, the yeshivah struggled financially, and its student body shrank significantly. Then the yeshivah received a new lease on life.

In June 1921 the Radin Yeshivah returned to Poland after a wartime exile across the Russian border, and its first stop was a ten-day respite in Baranovich. Eager to assist Rav Chaikel Sofer and Rav Lubchansky in their efforts to rebuild the yeshivah, the Chofetz Chaim prevailed upon his close student Rav Elchonon to assume its helm.

By 1924 the yeshivah had built a wooden structure of its own. But more importantly, under Rav Elchonon’s direction, it grew in both numbers and stature, emerging as one of the outstanding yeshivos of interwar Poland.

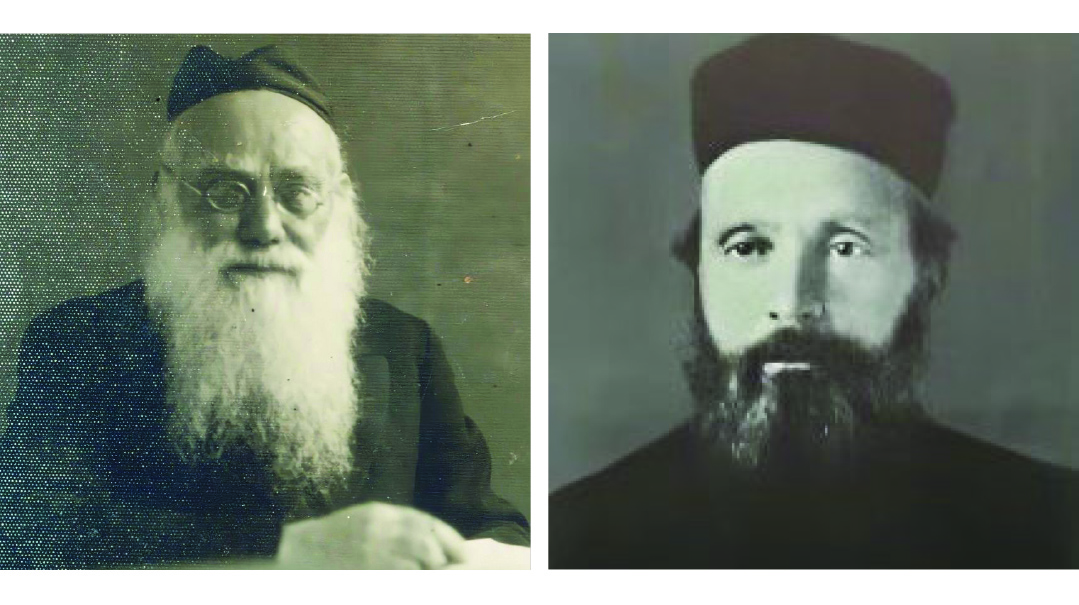

Members of the elite kibbutz (oldest Shiur) in Baranovich

A Yeshivah Like No Other

Rav Elchonon utilized a very calculated and forward-thinking vision as he transformed Ohel Torah from a struggling yeshivah on the edge of Poland — and the edge of the Torah world’s consciousness — into a pulsing center of Torah life and learning.

The staff in Baranovich included Rav Shlomo Heiman (until his departure to the Rameiles yeshivah in 1928), Rav Dovid Rappaport, the famed author of the Mikdash Dovid, and the great tzaddik, Rav Yisroel Yaakov Lubchansky, who served as mashgiach.

Primarily a yeshivah ketanah for teenage students, Ohel Torah consisted of six grades and an elite “kibbutz.” The first four shiurim were devoted to younger students, while the last two and the kibbutz were dedicated to older, more advanced students. No matter what a bochur’s level upon entry, the highest shiur he started at was the fifth shiur. After two zemanim (spanning one year) in the fifth shiur, the bochurim could proceed to the sixth shiur, where they would remain for a year and a half before moving up to the kibbutz. Rav Elchonon used to say that “even if Mar Bar Rav Ashi came to yeshivah he would start in the fifth shiur.”

Unlike other European yeshivos, where shiur was said once or twice a week, Rav Elchonon delivered a shiur twice daily (for grades five and six). The kibbutz would hear shiurim from him every Shabbos, and the Mikdash Dovid would give shiur to them twice a week. The twice-daily shiurim were so taxing that occasionally Rav Elchonon would collapse out of sheer exhaustion and put his head down to rest for five minutes.

While they may have depleted his physical resources, Rav Elchonon’s shiurim also distinguished his yeshivah across the European Torah landscape. They were clear, precise, and rarely went beyond their allotted 45 minutes. There were no diversions and only relevant materials were included. Students followed his initial presentation with questions. Most of the time Rav Elchonon covered an amud (page) of Gemara in his shiur, but the students were required to finish the daf (full folio, comprising two pages) with the sources that he assigned them. Utilizing this methodology, the students were able to master the foundations of the learning process and quickly advance so that they were able to study independently.

Due to Rav Elchonon’s stature and shiurim, Baranovich gained a reputation as the premier yeshivah ketanah in the country. Graduates would continue their studies in Radin, Kaminetz, Mir, and other elite yeshivos (see inset).

Several other practices set Baranovich apart. In tribute to Rav Elchonon’s prime mentor, the Chofetz Chaim, Baranovich was the only yeshivah that studied Mishnah Berurah as part of its curriculum. The daily seder, held immediately following Shacharis, was usually led by Rav Elchonon himself.

While his maamarim on hashkafah were legendary, and his many seforim, including Kovetz Maamarim, Ikvesa D’Meshicha, Kovetz He’aros, and others are still revered today, countless memoirs from talmidim make it clear that the traditional mussar shmuess had little place within the walls of the yeshivah, which he saw as a place for pure, unfiltered Torah. When it came to inculcating proper behavior, Rav Elchonon preferred to lead by example. Watching him was enough. Every action, every word, was measured and methodical, driven by a quest for emes — another legacy of the Chofetz Chaim.

Once while Rav Elchonon was visiting Telshe, a young Rav Mordechai Gifter entered his room as he was eating breakfast. He was surprised to see a Yiddish newspaper spread out on the table before the eminent rosh yeshivah. Noting the surprised expression on his face, Rav Elchonon elaborated, “A Jew must find time to read the newspaper, and to write to the newspaper… and to review all of Shas once a year,” and with that he resumed his eating and reading. (Rav Elchonon did in fact correspond with newspapers regularly.)

There was something else that distinguished the yeshivah from its counterparts: its student body contained a rare mix. The new Slonimer Rebbe, Rav Avraham Weinberg, established his court in Baranovich and enjoyed an amicable personal relationship with Rav Elchonon. Rav Elchonon’s appreciation for chassidim was noticed and soon his yeshivah became popular among Poland’s chassidic bochurim. Rav Elchonon would encourage them to carry their mesorah proudly and not cut their peyos or beard in order to “fit in” with the Litvish students.

While some Polish chassidim considered the Lithuanian bochurim’s modern dress and appearance suspect, when a chassid asked the Imrei Emes of Gur whether he should send his son to study in Baranovich, the Rebbe answered emphatically, “To Rav Elchonon, what question could there be?”

Noted author (and Baranovich student) Chaim Shapiro described the coexistence of these demographics in the town. Late at night, when he’d walk to his lodgings after night seder, he would hear the voices of the ba’alei mussar wailing from the nearby Jewish cemetery: “What is man’s obligation in this world? Ai, ai, ai …” and from the other side of the dark cemetery he’d hear the distinct voices of the local Breslover chassidim (several of whom studied at the yeshivah) screaming with all their might, “For such is the sum of man; no man dies with even half of his desires in his grasp!”

Nine Measures of Poverty

But while the yeshivah flourished in the spiritual realm, it struggled mightily to provide its students with even the basics of physical sustenance.

During the early years after its inception, the yeshivah received ample funding from the American Central Relief Committee. By 1923 that source had mostly dried up. Rav Elchonon would often remark sardonically, “Of the ten measures of poverty that descended to the yeshivah world, Baranovich took nine and the rest of the yeshivos one.”

The yeshivah was constantly strained by debt. Meals were regularly skipped. Rav Elchonon once said, “We have three machers (producers) in the yeshivah: Rav Dovid Rapapport macht seforim, Rav Yisrael Yaakov macht ba’alei teshuvah (repenters), und ich macht choivos (debts).”

When the yeshivah struggled to complete its new stone building in the early 1930s, the Chofetz Chaim tried to assist, writing a rare letter of recommendation addressed directly to the Jews of Baranovich. He encouraged each of them to donate generously “since whoever helps now in the construction of this sanctuary is [regarded] as if he had indeed participated in the building of the Beis Hamikdash.”

While planning his famous Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin, Rav Meir Shapiro embarked upon a tour of the great Lithuanian yeshivos to observe which elements he could incorporate in his visionary institution. Upon his arrival in Baranovich during Minchah, a thunderous “Amein yehei Shmei rabba’’ emanated from the mouths of the hundreds of talmidim. Rav Meir stood stunned in the doorway. He then embraced a shocked Rav Elchonon, stating emphatically, “This is Hashem’s army!” Rav Elchonon nodded proudly in agreement.

Rav Meir’s mood changed when he saw the abject poverty of the yeshivah. He offered Rav Elchonon an appointment in his soon-to-be-built Chachmei Lublin, where he would enjoy much better conditions. Rav Elchonon’s reply was not slow in coming. “But what will I do with all my children?” he asked, pointing to the hundreds of students in the beis medrash.

Rav Elchonon traveled to England, Belgium and Germany in his attempts to procure funding for the yeshivah, but the struggle remained. Once when his son Naftali Beinish asked him for a new coat, he refused. “You are not an only son,” he said. “I have hundreds of sons in the yeshivah, and not all of them have coats.”

Following the passing of his wife in the early summer of 1935, Rav Elchonon’s health began to deteriorate rapidly. Doctors recommended that he travel to the spas in Marienbad to recuperate. Upon his arrival, an urgent telegram arrived: The yeshivah’s suppliers had stopped deliveries because they hadn’t been paid in months.

In his distress, Rav Elchonon approached the great Imrei Emes, Rav Avraham Mordechai Alter of Gur, who was also in Marienbad at the time, and described the dire financial state of the yeshivah.

“How can I help you?” the Rebbe asked, to which Rav Elchonon replied, “It would be helpful if the Rebbe summoned ten of his wealthy chassidim and asked each to donate 250 zlotys, for which the Rebbe would bentsh them.”

Nodding, the Rebbe summoned a well-off chassid. “This is Rav Elchonon, the leading disciple of the Chofetz Chaim,” he told the chassid. “The students of his yeshivah are starving. It would be proper to contribute 250 zlotys.” Without a word, the chassid pulled out 250 zlotys and handed them to the Rebbe.

“But what about the blessing?” Rav Elchonon said. “Was it not agreed that each donor should receive a blessing?” The Rebbe acceded to this request as well. The Rebbe called one chassid after another, each of whom immediately acquiesced until the full amount was raised.

His mission accomplished, Rav Elchonon raised another matter. “I have been struggling with a particular Tosafos in Menachos. Perhaps we could discuss it…” In stark contrast to his characteristic brevity, the Rebbe delved into the sugya with Rav Elchonon for nearly 30 minutes.

But that was a rare respite from the constant fundraising burden. Clearly, new avenues had to be explored in order to support the yeshivah. It was time for Rav Elchonon to turn to his last resort: a trip to America.

My Bochurim Need Bread

While great roshei yeshivah like Rav Meir Shapiro, Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz, Rav Eliezer Yehuda Finkel, Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein and the Ponovezher Rav had traveled to the United States in the 1920’s, such visits greatly diminished with the onset of the Great Depression. When Rav Elchonon advanced plans to visit in the late 1930’s, the Torah-faithful Jews of the goldene medinah were excited: they saw his visit as a golden opportunity. The respect Rav Elchonon commanded could help raise the prestige of America’s fledgling Torah institutions, and his clear vision could guide them as they expanded the groundwork for a proper Torah infrastructure in the new world.

But not everyone shared their excitement. When Rav Elchonon’s talmidim in Baranovich learned of the planned trip, they offered to forgo a meal a day rather than have their Rebbi leave them. While touched by his students’ mesiras nefesh, Rav Elchonon felt that the trip was absolutely necessary to save the yeshivah, and would not be swayed.

Rabbi Avraham David Niznik ztz”l, av beis din of Montreal, could never forget the firsthand testimony that he heard from an older man who recalled Rav Elchonon’s arrival in America on October 18, 1937:

“I remember the excitement that preceded Rav Elchonon’s arrival in America. All the talmidei chachamim and all the yeshivah students were anxiously awaiting his speech. He was a legend, and we were sure that, true to his reputation, he would deliver a brilliant, incisive speech. Instead, Rav Elchonon ascended the podium and said, ‘Rabbosai, the Gemara (Yoma 75a) says that it is improper to request meat. But I am not asking for meat. I only ask for bread, and that is proper. Please help me give bread to my bochurim,’ and with that, he sat down. The simplicity and sincerity of his words tore through people’s hearts, and he was very successful (with his appeal).”

Upon his arrival, a reporter from the Morgen Journal asked Rav Elchonon, “How much money are you hoping to collect for the Yeshivah?” Rav Elchonon answered, “How much I will be able to raise was already determined by hashgachah (Divine Providence) and I will not collect more or less. How much hashgachah has been allotted? This I do not know.”

During the ensuing months, Rav Elchonon traveled across the country, visiting dozens of communities in an effort to attain financial solvency as well as to create a base of future donors who would provide funds for the yeshivah on a yearly basis. He refused to kowtow to the American style of fundraising, and eschewed all gimmicks, empty promises or unworthy endorsements.

At the time, the Religious Zionist Mizrachi party dominated religious life in the United States. This didn’t bode well for the fundraising prospects of the yeshivah world’s most outspoken opponent of Zionism. Still, Rav Elchonon refused to deviate from his “un-American” platform. Counterintuitively, many leading Mizrachi figures advocated his cause, despite his public criticism of the movement’s hashkafic foundations.

All in all, he saw mild success, raising approximately $10,000 ($182,000 today). His greater achievement was entirely different: During those 17 months, he helped pave the way for uncompromised Torah life and learning in America.

By the time Rav Aharon Kotler arrived in 1941, there was already a small cadre of Torah leaders with ambitious plans for the construction of Torah institutions, a testament to the success of Rav Elchonon’s mission. Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz, Mike Tress, Irving Bunim, Rav Shimon Schwab, and Rabbi Moshe Sherer were just a few of the changemakers whose missions were shaped and fueled by Rav Elchonon during his stay on American soil. He left them — and ultimately This World — two years later, but he also left them the tools and convictions to transplant his legacy to a new generation.

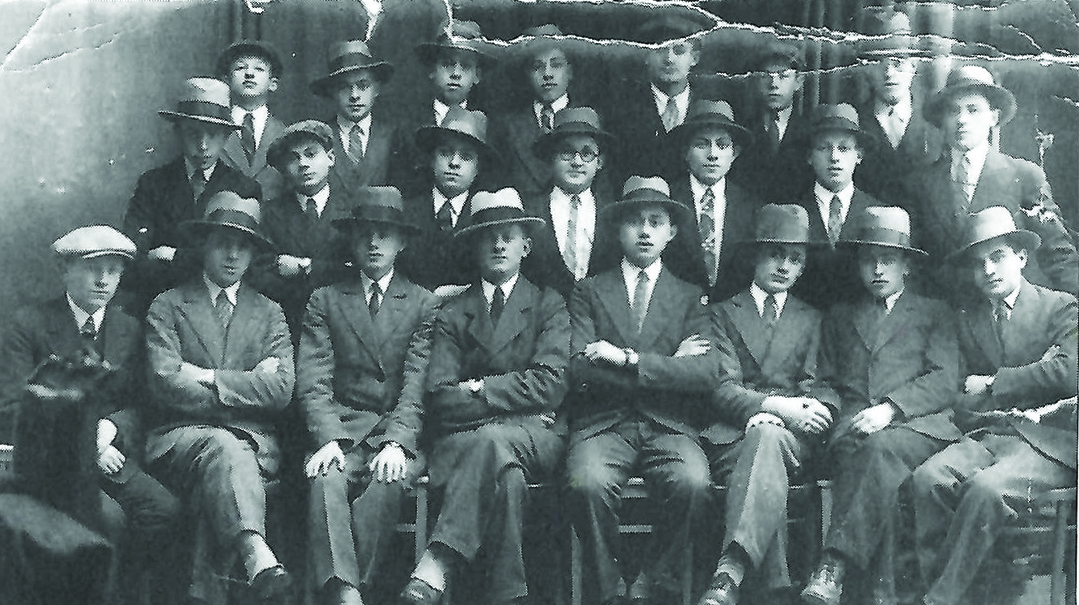

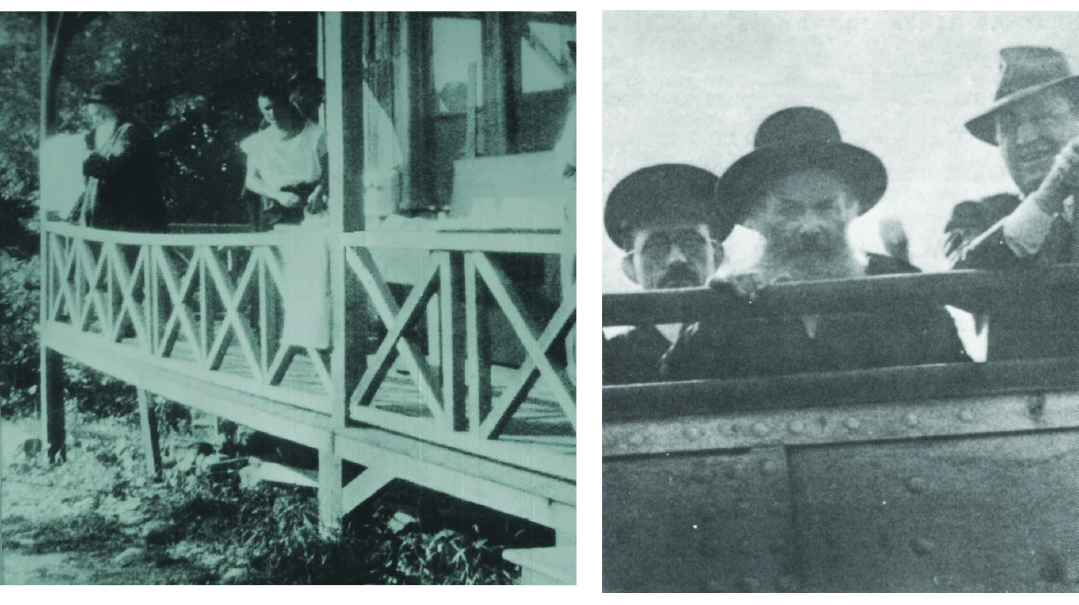

(Left) When Rav Elchonon visited Camp Mesivta in Ferndale, NY in August 1938, Louis Glick (posing) was one of the Torah Vodaath bochurim who attended to him.

(Right) “I’m a soldier, I have to go to the front.” Rav Elchonon on the deck of the ship returning to Europe in March 1939

Quality Merchandise

Rav Elchonon was famously repulsed by the “odor of Gehinnom” emanating from Times Square and spent some of his time in Baltimore organizing a letter of protest against immodest customs being practiced in local shuls. Yet he was largely upbeat about the prospects for Yiddishkeit in America. All that was lacking, he insisted, was proper education:

“Everyone told me that America is not fit for Torah. But that is not true. On my travels I have seen many pure Yiddishe kinder (Jewish children), temimusdike kinder. In some respects, they are purer than the children in Europe. All that is needed is someone to teach them Torah. If people undertake to spread Torah, they will accept it.”

Years earlier, when Rav Shlomo Heiman first accepted the position of rosh yeshivah in Torah Vodaath, Rav Elchonon had been upset; he believed that Rav Shlomo would be better off devoting his energy to the bnei yeshivah of Europe. But when he arrived in America and visited Torah Vodaath, he observed a group of Rav Shlomo’s talmidim huddling around their beloved rebbi after shiur, discussing the sugya with great zest. The discussion continued afterward, with the students escorting Rav Shlomo home, immersed in deep conversation and oblivious to the cars and trolleys chugging alongside them. “Ahh,” said Rav Elchonon with pride, “Rav Shlomo hut yeh ibergekert America — Rav Shlomo has overturned America.”

Rav Elchonon also spent several weeks in upstate New York at Torah Vodaath’s Camp Mesivta, where he was joined for some time by Rav Moshe Feinstein. One day the Baranovich Rosh Yeshivah was asked to honor the students by giving a shiur, which resulted in an impressive Talmudic exchange. “I can see that the American bochurim are also capable of analytical Talmudic study,” Rav Elchonon commented. “You have some gutteh schoirah, some quality merchandise.”

One Shabbos morning, he was invited to speak at Young Israel of Williamsburg, where Yeshivah Torah Vodaath student Irving Silber was celebrating his bar mitzvah. Decades later, the Cleveland resident would recall Rav Elchonon’s resounding message: “An effort must be made to establish Jewish schools where youngsters will study Torah with Rashi’s commentary. This will saturate our children with faith in all of the cardinal principles of Judaism, in both our written and oral Torah.”

On the sidelines of the 1938 Agudath HaRabanim convention, Elimelech Steier interviewed Rav Elchonon for the Yiddishe Tageblatt.

He dominated the conference, surrounded by groups of rabbanim and roshei yeshivah and just plain delegates, all of whom praised his words. A tall, bent figure with a grey beard, he conveys massive inner resoluteness. A fierce zealot, a rebuker, a zero-compromise leader, who has one answer to any question he is asked — look what the Torah says. The Rebbe from Lithuania does not say a thing without mentioning the Chofetz Chaim ztz”l, whom he considers his Rebbe. In the Lithuanian Yeshivahs he is considered the successor of the Chofetz Chaim in both tzidkus and in mussar.

When he speaks everyone around listens with undivided attention. He makes authoritative statements, cites parables from the Chofetz Chaim, and his words hover in the air long afterward, implanting themselves in people’s hearts.

He has traversed America for an extended period of late, to collect necessary funding for his yeshivah, which was in bad financial condition, sunken in debt. Despite his age and health condition, he set out on a distant overseas journey, for the sake of the Torah. For the Torah he wholeheartedly sacrifices himself, and he demands the same from others — from all of Klal Yisrael.

The Youth is the Future

Throughout his stay, Rav Elchonon did not focus solely on the needs of his own yeshivah; he spent significant amounts of time with the impressionable youth of Zeirei Agudath Yisroel, and left his mark on the coming generation of American Torah leaders. He urged them not to make compromises in their observance, even as they watched so many around them capitulate to the lures of American opportunity.

He would host Friday night forums for the Zeirei boys at their makeshift headquarters at the Williamsburg home of the Stoliner Rebbe, where he treated the dozen high schoolers with the same reverence as the 1,000-strong crowd that greeted him at the Clymer Street Synagogue on his first Shabbos in the country.

Rav Elchonon would stand at the front of the room, Chumash in hand, and tell the boys that everything is found in the Torah. “Fregt ah kashe,” he would encourage the nervous youngsters. They would pepper him with questions about everything that bothered them — even Hitler’s meteoric rise to power in Germany — and he would respond by quoting various verses and explaining their relevance to current events.

Reuven Soloff, in whose parents’ home Rav Elchonon stayed for a period of time, described how he’d bring the Torah to life in an unprecedented way. “Whenever he was asked a question, he would jump up and say, ‘It’s an explicit verse or saying of Chazal!’ We saw that Torah is alive, and we are part of it, not that we are one thing and Torah is something else.”

Agudath Yisroel leader Mike Tress, who as a young man moved worlds to rescue European Jews from the Holocaust, was one of the youngsters transfixed and eventually transformed by Rav Elchonon. He recalled two lessons ingrained in him by Rav Elchonon. The first: never be disappointed by others’ lack of appreciation if you know your cause is just. The second was the importance of mesirus nefesh, a lesson that became embedded in his psyche and transmitted to the many he influenced.

Similarly, when addressing the women involved in founding the first Bais Yaakov in Williamsburg, Rav Elchonon emphasized that anything begun with mesirus nefesh (self-sacrifice) will come to fruition. He addressed the ladies’ auxiliary of the Baranovich Yeshivah (under the leadership of one of his venerable hosts, Mrs. Necha Golding) and extolled their hard work on the yeshivah’s behalf. When addressing women, he always highlighted the importance of encouraging their husbands and sons to study Torah, reminding them that by doing so they would acquire a portion of the reward.

Shraga Block was one of those who greatly assisted Rav Elchonon. Calling himself “Der Rebben’s Baal Agalah,” he volunteered to serve as Rav Elchonon’s personal driver during his stay in New York. Once he brought Rav Elchonon to meet the residents of his remote Brooklyn neighborhood of Brighton Beach, which lacked the resources to build schools for both boys and girls simultaneously. The question was which had priority.

Rav Elchonon replied that had he been asked the same question in Baranovich, he would have answered without hesitation that a yeshivah comes first. But in America, he said, a girls’ school must take priority. This decision, Rav Elchonon explained, is based on the halachic priority when it comes to ransoming Jewish captives: women must be redeemed before men. The same principle held true in this case.

Rebbetzin Vichna Kaplan, legendary founder of Bais Yaakov in the United States, was raised in Baranovich at the home of her uncle, Rav Yisroel Yaakov Lubchansky. When Sarah Schenirer opened the first Bais Yaakov in Cracow, she begged her uncle to allow her to attend. Wary of the new concept, Rav Yisroel Yaakov hesitated to grant his approval. Undeterred, young Vichna bravely walked over to the nearby Wasserman home and asked Rav Elchonon to intercede on her behalf, which he did. The rest, of course, is history.

Why I’m Here

Rabbi Moshe Sherer was among a group of Torah Vodaath students who attended to Rav Elchonon, later describing the experience as a “turning point in my life in a very big way.” He added that “Rav Elchonon was the type of person who left a searing impact on the neshamah of any young person who met him.”

The first morning that the young yeshivah student showed up to accompany Rav Elchonon from his accommodations, the gadol asked Moshe to teach him how to say “Gut morgen (good morning)” in English. Rav Elchonon practiced saying “Good morning,” until he was satisfied that he’d gotten it right.

“Why?” Rabbi Sherer would later explain. “Because he wanted to be able to greet the gentile elevator operator in a pleasant fashion, in accordance with the Gemara that describes Rabi Yochanan ben Zakkai as having been the first to offer greetings to every person in the marketplace — even a gentile.” It was a lesson not lost on the young yeshivah student who would eventually become one of the Torah world’s foremost representatives in the halls of power.

Rav Elchonon once made an appointment with “Philip Goldstein” (name changed), with whom he’d attended cheder as a boy. Mr. Goldstein was now the wealthy owner of a coat factory, but had long since abandoned Judaism, and rarely donated to Torah institutions. The old friends shared memories of their childhood, and spoke about what each had been doing since. After being brought up to date, Rav Elchonon turned to leave. Mr. Goldstein was confused.

“But… didn’t you come here for something?” he asked.

“As a matter of fact, I did come for something,” Rav Elchonon said. “I have a problem. There’s a loose button on my coat, and I know that you have a coat factory. Could one of your employees come and tighten up this button?”

Confused, Mr. Goldstein summoned an employee by telephone to come repair Rav Elchonon’s coat. The employee tightened all the buttons. “Now come on,” said Mr. Goldstein. “You must have come here for something more important than fixing a loose button.”

“No, that really was my reason,” said Rav Elchonon, as he thanked his friend once again and left.

The following day, Mr. Goldstein called Rav Elchonon and asked that he return to his office. Rav Elchonon arrived and found Mr. Goldstein in an agitated state. “It just doesn’t make sense. No one travels all the way from Europe to America just to fix a loose button. You could have had this done for you right there in Baranovich. Why did you come to me?”

“I already told you. I really came to you just for the buttons,” replied Rav Elchonon.

“That’s ridiculous!” Goldstein countered. “Tell me the truth; didn’t you come to ask for a donation to your yeshivah?”

“Let me explain what I meant,” began Rav Elchonon. “You refuse to accept that I would come such a long way just to tighten a few buttons. So I ask you: Why do you think that Hashem sent you all the way down to This World? Just to sew a few buttons? This is the reason why you’re here? All I did was travel a few thousand miles, whereas you came all the way from under Hashem’s throne of glory, and for what? To sew a few buttons?”

Final Prophecy

Compromise was not a word that existed in Rav Elchonon’s lexicon. He took the utmost precautions with regard to kashrus, and abstained from eating meat during his entire stay in America. An apocryphal tale is shared regarding his first night in the United States. Rav Elchonon was careful to drink only chalav Yisrael milk, which was a challenge to obtain back then. On the night of his arrival, he was served a cup of coffee with milk that he refused to drink. Yet in the morning a cup of coffee with milk was again brought to him. “Didn’t I tell you last night that I don’t drink milk?” he asked in astonishment. His host answered most seriously, “I thought that after spending a whole night in America you would have already changed your attitude somewhat.”

Rabbi Leo Jung, the longtime rabbi at The Jewish Center on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, was among those who assisted Rav Elchonon’s fundraising efforts in New York. Rabbi Jung, who was among the founders of Agudath Yisroel in America, had first met Rav Elchonon and the Chofetz Chaim at the 1923 Knessiah Gedolah in Vienna. From then on he used his influence as a member of the Cultural Committee of the Joint Distribution Committee to champion the cause of European yeshivos.

In his memoirs, Rabbi Jung recalled how a “stubborn” Rav Elchonon refused to waive his principles, even at a potential cost to the yeshivah. When spending Shabbos at Rabbi Jung’s Jewish Center, Rav Elchonon did not hold back from criticizing the shul for having a (gentile operated) elevator running on Shabbos, even though that was considered the norm in American Orthodoxy at the time.

Toward the end of 1938, Rav Elchonon’s son Rav Simcha Wasserman joined him in America, where he would stay to follow up on the multitude of pledges Rav Elchonon had received. That move would save his life.

In March of 1939, Rav Elchonon declared that he was returning to Europe. His American confidants begged him to stay, but he refused. “I don’t have only three sons,” he said, “I have hundreds — the yeshivah bochurim. How can I leave them?” When asked how he could justify returning to a potential powder keg, Rav Elchonon answered unequivocally, “I am a soldier; I have to go to the front.”

The last people to speak to Rav Elchonon before he boarded the ship back to Europe were Mike Tress and the young leaders of Zeirei. At their parting, Rav Elchonon told Mike that nothing less than the fate of Torah Jewry rested in his hands. Rav Elchonon recognized that whatever hope remained for the salvation of European Jewry lay with Mike and his band of dedicated activists.

Six months after Rav Elchonon’s return, Germany invaded Poland, launching the Second World War. With Baranovich under siege, the yeshivah fled to Vilna, where it thrived under difficult circumstances. In June 1940, when the Red Army occupied Lithuania, Rav Elchonon relocated the yeshivah to Semeliškės, a small village outside Vilna and away from the prying eyes of the Communists. Even there, they were oppressed for keeping the yeshivah open. Eventually Rav Elchonon disbanded the yeshivah and advised the students to head for safer locales.

In early June 1941, Rav Elchonon and his family attempted to flee north to Sweden, from where they would travel by boat to the United States. Their bags were packed, and a wagon arrived. As his son Rav Naftali was loading his bag, it fell and broke his leg. The escape was rescheduled for a few days later. In the interim, the Germans invaded the Soviet Union, ending Rav Elchonon’s plans.

Rav Elchonon spent his final days at the Kovno home of Reb Aryeh Malkiel Friedman, which adjoined the Grodzinski home. As the roundups and brutal massacres unfolded around them, Rav Elchonon struggled to answer the question that was on everyone’s lips: Why? When he was approached and asked, “Why my mother and father?” “Why my wife and children?” he had nothing to reply. “I still don’t know the answer to that question,” Rav Elchonon told his students, “but at least I understand why the question cannot be answered.” He then proceeded to relate the following parable:

Once a man who knew nothing at all about agriculture asked a farmer to teach him about farming. The farmer took him to his field and asked him what he saw. “I see a beautiful piece of land, lush with grass,” he said — then stood aghast while the farmer plowed up the grass and turned the beautiful green field into a mass of shallow brown ditches.

“Why did you ruin the field?” he demanded.

“Be patient. You will see,” said the farmer.

Then the farmer showed his guest a sack full of plump kernels of wheat and said, “Tell me what you see.” The visitor described the nutritious, inviting grain — and then, once more watched in shock as the farmer ruined something beautiful. This time he walked up and down the furrows, dropped kernels into the open ground, and covered them with clods of soil.

“Are you insane?” the man demanded. “First you destroyed the field, and then you ruined the grain!”

“Be patient. You will see.”

This continued with every subsequent stage of the process of cultivating, harvesting and grinding the wheat, with the visitor questioning the farmer’s every move.

Finally, the farmer opened the oven and took out a freshly baked bread — crisp and golden, with an aroma that made the visitor’s mouth water.

“Come,” the farmer said. He led his guest to the kitchen table where he cut the bread and offered his now-pleased visitor a liberally buttered slice.

“Now,” the farmer said, “now, you understand.”

“Hashem is the Farmer and we are the fools who do not begin to understand His ways or the outcome of His plan,” Rav Elchonon told his students as the footfalls of destruction grew louder. “Only when the process is complete will the Jewish people know why all this happened. Then, when Mashiach has finally come, we will know why everything — even when it seems destructive and painful — is part of the process that will produce goodness and beauty.”

“We Were Chosen”

Rabbi Ephraim Oshry, one of the few survivors of the Kovno ghetto, remembered how Rav Elchonon spent his final days in the Friedman attic, learning hilchos Kiddush Hashem with his son Naftali Beinish.

In the beginning of July 1941, a wave of mass arrests hit the Jewish population of Kovno. Rav Elchonon was eventually arrested by local Lithuanian youths who eagerly assisted the Nazis in their evil work. Rav Yitzchok Elchonon Gibraltar witnessed Rav Elchonon being led away together with a large group. He recalls how Rav Elchonon walked in his usual dignified style, lost in his holy thoughts. “It was hard to tell who was leading who,” Rav Yitzchok Elchonon described the scene.

Rav Elchonon was taken to the Seventh Fort outside Kovno, where thousands of his fellow Jews were being held. The weather was unusually hot, and the Jews were kept for days in the open yard of the fort, under the burning sun, without a drop of water. They were not allowed to make a move; the patrolling Lithuanians opened fire on anyone caught raising his head or speaking to his neighbor. During this time, the Germans held a basketball match with the Lithuanians. The Lithuanians, who’d had a championship team before the war, handily defeated the Germans. As a “reward,” each of the Lithuanian players was allowed to come to the Seventh Fort and shoot a dozen Jews.

For 24 hours, Kovno’s Jews desperately tried to secure Rav Elchonon’s release by persuasion and bribery. They failed. On Monday Night, 13 Tammuz, 5701 (July 8, 1941) under the command of SS Commander Karl Jager, thousands of Jews were machine-gunned to death at the Seventh Fort, Rav Elchonon among them.

It is told that when he anticipated the end was near, Rav Elchonon spoke to those around him in the same calm and collected tone he always did, with no indication of panic: “In Heaven it seems that they consider us to be tzaddikim, because we have been chosen to be korbanos (martyrs) for Klal Yisrael. Therefore, we must repent now. We don’t have much time. We must keep in mind that we will be better korbanos if we repent. In this way we will save the Yidden in America. Let no foreign thought enter our minds, chas v’shalom, as that will make us pigul, an unfit korban. We are now fulfilling the greatest mitzvah. Yerushalayim was destroyed with fire and will be rebuilt with fire. The same fire that will consume our bodies will one day rebuild Klal Yisrael.”

Indeed, the bodies of Rav Elchonon Wasserman, most of his family, the yeshivah’s rebbeim and most of its students were consumed in the flames of the Holocaust. But a far greater fire had been ignited prior to the blaze of destruction. Rav Elchonon had kindled a fire in the hearts and souls of all who knew him, a force that would ultimately rebuild the Torah world in the postwar era. Rav Elchonon’s fire would not only prevail; its warmth, light and uncompromising pursuit of truth would shine for decades to come.

This article is dedicated to the memory of my great uncle and aunt, Rav Nachman Dovid Kop and Rebbetzin Bella Kop and their family. Rav Nachman studied in the Mir and the Kollel Kodshim in Radin before moving to Hajnowka, where he served as the Rav as well as the regional representative of the Vaad Hayeshivos. Rav Nachman was martyred by the Nazis 80 years ago on 30 Sivan. His wife and seven children were murdered a short time later in Auschwitz. Hashem Yikom Damam.

Note: The comprehensive works and vast knowledge of the following esteemed authors, lecturers, researchers and dear friends were utilized in the preparation of this article: Yehuda Geberer, Aaron Sorasky, Yonoson Rosenblum, Moshe Benoliel, Rabbi Shimon Finkelman, Dr. Lester Eckman z”l, Rabbi Dr. Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff, Professor Ben-Tsion Klibansky, Rabbi Dr. Hillel Goldberg, Rav Yitzchok Elchonon Gibraltar z”l, Solly Ganor z”l, Rav Aaron Lopiansky, Mrs. Devora Glicksman, Professor Marc Shapiro, Chaim Shapiro z”l, Dr. Zev Eleff, Rabbi Joseph Kirsch, Baruch Wenger, Yehuda Zirkind, and Nachum S. Zajac.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 865)

Oops! We could not locate your form.