The Chida’s Riddle

| March 22, 2022The blanks in an 18th century mystery are finally filled in

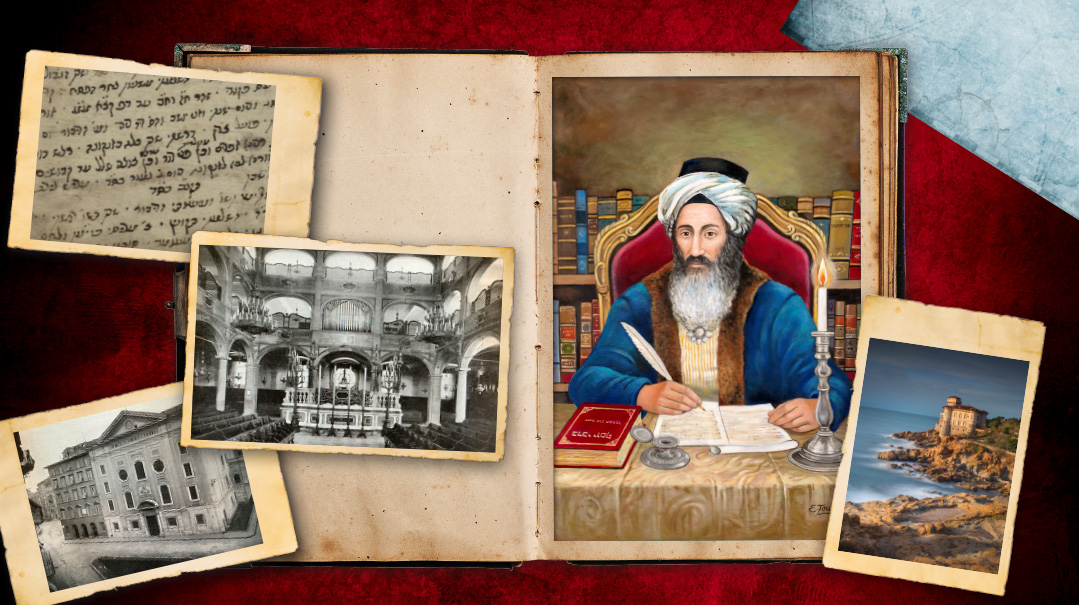

Although more than 200 years have passed since the passing of the Chida on Shabbos parshas Zachor, much of his rich and colorful life is still a mystery waiting to be uncovered. While until today Torah scholars toil over his dozens of books and writings, Rav Chaim Yosef David Azulai ztz”l, known by the acronym Chida, is a riddle, as his acronym (“chidah”) implies.

The Chida, who was born in Jerusalem in 1724, was one of the most prolific authors in the Torah world, having compiled over 80 seforim (60 of them in print) on an array of subjects in all areas of Torah, halachah, Aggadah and Kabbalah. He was also a meticulous researcher and bibliographer 200 years before computers could help out, and he was one of the only gedolim to pen an autobiography of his life, in the form of manuscripts that encompass and record the details of his many and varied travels. Some of those reports had been compiled into his famed travel diary, Ma’agal Tov.

A reader of this sefer flows with the ups and downs of the Chida’s life, commiserates with his challenges and rejoices in his successes and gratitude, and receives a comprehensive first-hand account of Jewish life and historical events throughout the Europe and Near East of his day.

But it turns out that this famous diary was not the end of the Chida’s story.

“Even after the sefer was printed,” says Rabbi Daniel Biton, head of the Hamaor Institute which has been republishing the Chida’s works, “the Chida continued to travel and to write. But these writings remained in hard-to-decipher manuscript form, and few people knew they even existed. Now, the time has come to reveal them and fill in the blanks.”

Far from Home

Growing up in Jerusalem, the Chida, who identified himself a Sephardi and whose works have formed the foundation of Sephardic halachic mesorah, remained strongly connected to the Ashkenazi lineage of his mother’s family (he was named after his maternal grandfather, the German gadol Rav Yosef Bialer) and served as a bridge to both traditions. From childhood, he was a student of the great kabbalists Rav Shalom Sharabi (the Rashash) and the Or Hachaim, at age 13 he was giving public Torah classes, and at 16 he wrote his first sefer.

In 1753, when only 29, the Chida was appointed as an emissary to represent the Holy Land abroad, and specifically to raise funds for the destitute, hard-pressed Jewish community in Chevron. This wasn’t the job of a shnorrer; rather, it was tremendous honor. There was a custom to send a person of great stature, inspiration and scholarship as a representative of the yishuv in Eretz Yisrael to visit Jewish communities elsewhere, both to raise funds, and to keep an interest in Eretz Yisrael on the front burner.

The Chida, who viewed this role of “shadar” (shaliach d’rabanan) as a personal obligation for the honor of Eretz Yisrael, spent five years in this first round of travel, spending time in such countries as Egypt, Italy, Germany, Holland, England, France, Sicily, Rhodes, Turkey and Syria, visiting 160 cities in all and raising significant funds for the Jews of Eretz Yisrael. And being a great lover of books and learning and having a photographic memory, the mission was also a great opportunity to spend time in the libraries of the cities he visited, studying ancient manuscripts and books.

The Chida’s position as shadar was actually the least-known period of his life, even though he eventually traveled on these years-long fundraising and ambassador missions at three different times during his lifetime. Being a fundraiser back then was no easy task: The right candidate had to combine the qualities of statesmanship, charisma, stature, physical strength and endurance, Torah knowledge and understanding, and the ability to speak multiple languages. In the communities he visited, he’d often be summoned to arbitrate matters of Jewish law for the locals, and would have to be able to communicate with the local Jews and gentiles alike.

And, he’d have to be willing to undertake the dangerous, time-consuming mission that would take him away from his family for months or years. Emissaries would often divorce their wives before leaving, so that if they died along the way and their deaths could not be verified, their wives would be able to legally remarry. If they returned safely from their journey, they would remarry their wives, who would sometimes wait as long as five years for their husbands to return from their mission.

The Chida was a perfect candidate. He was a top-tier Torah scholar, spoke many languages, and in addition was a sharp-witted conversationalist with an engaging sense of humor. With his remarkable blend of charisma, humor, scholarship, eloquence, worldliness, common sense and human understanding, he inspired audiences, successfully resolved countless communal conflicts, and impressed everyone he encountered.

Yet his trips weren’t VIP-class excursions. In the Chida’s diaries, he records many instances of miraculous survival and dangerous threats, including a run-in with the Russian Navy during the Ali Bey uprising against the Turks. During a winter trip to Amsterdam, he sustained a head injury after slipping on an icy street. He lost consciousness for a short time, but after regaining it, discovered that his vision had been affected by the injury. He prayed with all his might, beseeched Hashem to restore his sight, and to the amazement of all present in the shul where he’d been brought, after his intense prayers he was once again able to see.

He writes how he often slept at night on a public wooden bench, yet also made sure to diligently study 53 pages of Zohar every day. Despite the hardships, he took advantage of the opportunities to meet great Torah scholars in other lands and search out rare books and manuscripts, visiting numerous libraries and genizah collections where he’d spend nights copying rare texts by hand. He’d rummage through dusty basements of museums, libraries and private collections in search of centuries-old treasures that even many scholars didn’t know existed.

But according to Rav Biton, the Chida might have had more esoteric reasons for his journeys, which he alluded to in one of the new-old manuscripts: “Every tzaddik who goes from place to place is able to filter out the holy sparks that are connected to his soul.”

And it seems his manuscripts were actually a balm to his spirit on these journeys when he was alone, isolated and very far away. While on one of his later trips, his wife passed away, and he learned about it via telegram.

The Last Stop

Upon returning from his first five-year excursion, he spent six years in study and research in his native Jerusalem. Then he was called again to undertake a mission to the Sultan of Turkey, where the Jews suffered great hardships under his rule. The Chida, who greatly impressed the Sultan, was able to help improve the position of the Jews there. He was then invited to become rav of the Jewish community in Cairo, Egypt, a post he held for the next five years. During that time, he unearthed many ancient genizah collections of scrolls and manuscripts, which further enriched his vast knowledge. Eventually his wife and children joined him in Egypt, but tragically, one daughter died there.

After returning to Eretz Yisrael where he immersed himself in the study of Kabballah for the next few years, he was again summoned by Diaspora communities who needed him as their spokesman. The Chida’s regal features and bearing made a deep impression on everyone, Jew and non-Jew alike, and diplomatic missions on behalf of the Jews often took him to the courts of kings. When he visited King Louis XVI of France, before he had a chance to introduce himself, the king was so impressed by his countenance that he mistook him for a foreign ambassador.

Finally, in the year 1778, several years after his wife passed away, the Chida was invited to Livorno (Leghorn), Italy. He never officially took on a title there, but he became the de facto chief rabbi, remarried, and settled down to write some of his major works. At the time, Livorno was a center of Jewish printing, and with the help of generous friends and supporters, the Chida was able to devote all his time to his writings without financial worry.

One of the Chida’s major works during this time was his classic Shem Hagedolim, an encyclopedic compilation of names and entries of some 1,500 scholars and authors, and entries for as many works, both published and unpublished. Many of the seforim mentioned had never been heard of, and important facts about them and their authors would surely have been lost to modern scholars if not for this great work — which the Chida wrote over the course of just a few weeks, primarily from the information he carried in his own vast memory bank. It was republished over the years and remains one of the most important and invaluable source books of Torah commentary and Jewish literature and history.

The Chida remained in Livorno until his passing on Shabbos Zachor in 1806. He was buried there, but in 1960, more than 150 years later, his remains were returned to Jerusalem, the city of his birth, and reinterred in Har Hamenuchos.

Days of Serenity

But many have wondered over the years: Why did the Chida remain in Livorno instead of returning to Chevron or Jerusalem? From the unpublished manuscripts of the last part of the Chida’s life, Rabbi Biton has the story. The Chida arrived in Livorno during the time of a raging machlokes. It began as a family drama in which one woman was accused of a great sin, and developed into a painful, stormy debate with halachic ramifications between two batei din. Entire families were torn apart; groups stopped marrying into one another. It seemed that the entire Livorno community’s future was in danger.

Then the visitor from Chevron arrived. The community members asked him to get involved, and he spent several days discussing, studying, and garnering testimony. Then he convened all the members of the community in the big shul to announce his verdict: The woman, he determined, had indeed sinned. People in the crowd were outraged, and the storm was now directed at him.

But the Chida was undeterred. “Morai verabbosai,” he announced, “you asked for a halachic ruling, and you got it. Do you want me to prove it with miracles?” Silence fell. Someone from the losing side stepped forward.

“Yes, give us a miracle.”

Livorno never forgot that moment. The Chida summoned the woman, and then took out a sefer Torah and began to read the pesukim related to the sin. “Read after me, word for word,” he instructed her. When the reading ended, the Chida asked that the woman be taken out of the shul. She never made it. On the second step, she fell and died, exactly the way it is described in the pesukim.

The members of the community, who were in a frenzy over this story, begged the Chida to stay and live among them, to be their guide and teacher. And having seen a miracle in front of their eyes, they even changed that step to a golden step.

It turns out that those were the most tranquil years of the Chida’s life. The wealthy Italian community supported him and took care of him. He learned and taught, and had no worries or burdens. And it turns out that even during those years, the Chida continued to record his life — although until recently, no one knew about it. Those manuscripts were never published. What was happening in the Chida’s inner world during those last decades of his life?

Rabbi Biton decided to make order out of the entire sefer Ma’agal Tov. After years of all the print editions essentially being photocopies of old, broken type, he decided to enhance it and begin from scratch, and to crown the work with the never-before published final chapter of the Chida’s life as well.

Rabbi Biton also discovered a fascinating kuntress written by the Chida called Kan Sipur, which is, as its name implies, one hundred and fifty (numerically equivalent to “kan”) stories written in the Chida’s own hand that few have ever heard.

One of the stories in this booklet is about a kol korei that Shulchan Aruch author Rabi Yosef Karo wanted to issue, banning visits to the tziyun of Rabi Shimon Bar Yochai on Lag B’omer, because of the kashrus of the food and tzniyus problems. That night, Rabi Shimon bar Yochai appeared to him in a dream and said, “Rabi Yosef, don’t issue it, I want these people by me.” The Chida relates that the next day, the Beis Yosef tore up the kol korei and never published it.

The Chida was so confident, so engaging and so larger-than-life. Yet in these diaries, there is revealed an entirely different side of him — a certain frailty, as a servant quaking in front of his master. In one of the diaries, the Chida shares his practices on the days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur: “From Erev Rosh Hashanah until Yom Kippur, I fasted during the weekdays and did not speak to anyone. At night, I ate a small pastry. I didn’t sleep, but from time to time I dozed for a bit in my place…”

In these final diaries, the Chida focuses primarily on two subjects — his special practices relating to the festivals of Tishrei, and his personal learning seder. He writes succinctly, with just a few words and little detail: “Evening of 16 Cheshvan, I completed Zohar Chadash … with siyata d’Shmaya. I completed Shulchan Aruch from the Arizal’s girsa.”

The Chida had a lingering illness, but he writes that despite being ill, he kept up his ascetic practices. “Chasdei Hashem, although I was sick with my old ailment, and in my eyes, Hashem bestowed His kindness on me, and I fasted on Erev Rosh Hashanah… and I fasted days in between, and one day when I was sick I slept on the bed for a few hours. At night, I drank chicken soup. And I didn’t speak, as is the practice. And I spoke on Shabbos Teshuvah, despite being ill, for some two hours…”

The following summer, the Chida writes that he again took ill, and he even canceled his daily schedule. “On Shabbos Kodesh Seitzei, I was sick, and it continued until Rosh Hashanah, and because of that, I canceled a few things, including two weeks that I did not learn Tehillim and mitzvos and the like, Hashem should have mercy on me and send me a full recovery, kein yehi ratzon.”

This severe ailment lasted several months, during which time, after Yom Kippur, the Chida writes: “Through Hashem’s chesed and compassion, even with my ailment I could speak on Shabbos Teshuvah for close to two hours. I fasted on Erev Rosh Hashanah and on all the days of teshuvah, and at night I ate soup, and slept a bit more than an hour… but Rosh Hashanah and Shabbos I barely slept at all…The Tehillim I said sitting, but I could not say Selichos as is the custom. And today, I was in pain from my ailment, and a bit of the Selichos, and also I missed one ‘Vaya’avor’ of Minchah and I was in great distress over Ne’ilah, and Hashem in His Kindness gave me strength and I said it better than the other years, thank Hashem.”

What becomes clear from his later writings is that during the final part of his life, when adventure was behind him and life became quiet, the Chida rarely traveled, and in fact, and surprisingly, relished being alone. “I kept to myself, Hashem helped and I didn’t receive any visitors,” he writes.

When Rabbi Biton is done processing the treasure trove of these latest discoveries, he’ll try to give the world a more complete picture, but there still remain many questions surrounding this humble gadol who had no problem visiting heads of state on behalf of downtrodden Jews, who wrote dozens and dozens of seforim and revealed ancient genizahs, and yet who at the end of his life, just relished solitude and quiet. It seems the Chida will always be a riddle. —

Rachel Ginsberg contributed to this report.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 904)

Oops! We could not locate your form.