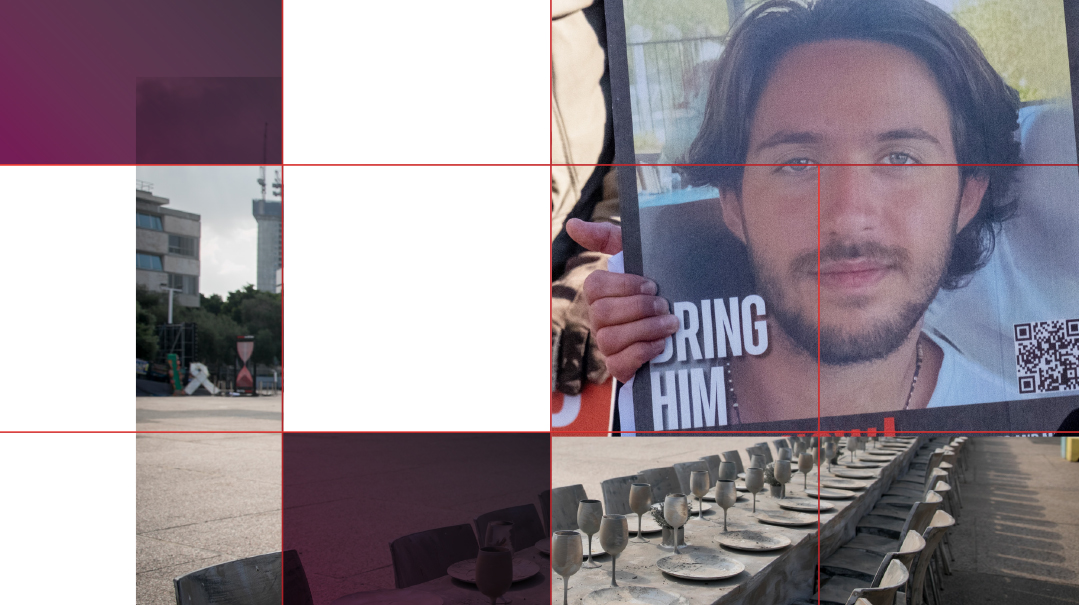

The Brother I Never Knew: The Power of a Hug

After October 7, unlikely yet remarkable human connections have emerged out of shared purpose and resilience

In the wake of the tragic events of October 7, unlikely yet remarkable human connections have emerged out of shared purpose and resilience. Through their collaboration, they developed new perspectives and understanding of the other’s world, and achieved something greater than themselves, as they learned to see beyond differences, bridging divides that once seemed insurmountable. Here are their stories.

When Meir Tubul’s son was killed in Gaza in December 2023, Meir became angry at G-d, shaking his fist at the Almighty and refusing to do any of His mitzvos. But an embrace from Mendy Henig, a Biala chassid who took upon himself to do something important for bereaved families, brought back the spark of hope.

A

fter Seargent Major Asaf Pinchas Hy”d, died in combat last winter, his father Meir Tubul — a typical Sabra with a tough personality and a sweet, kind nature — didn’t need anyone telling him anything.

“After my son’s death, I got tired of hearing certain phrases. For example, that G-d takes the ‘best ones,’ ” he says. “It’s pretty ironic. If He takes the best, what are those of us left here on earth? The worst?”

He pauses.

“Another thing I don’t like is when people tell me that Avraham Avinu was willing to sacrifice his son. First of all, I’m not Avraham Avinu. But also, no one asked me.”

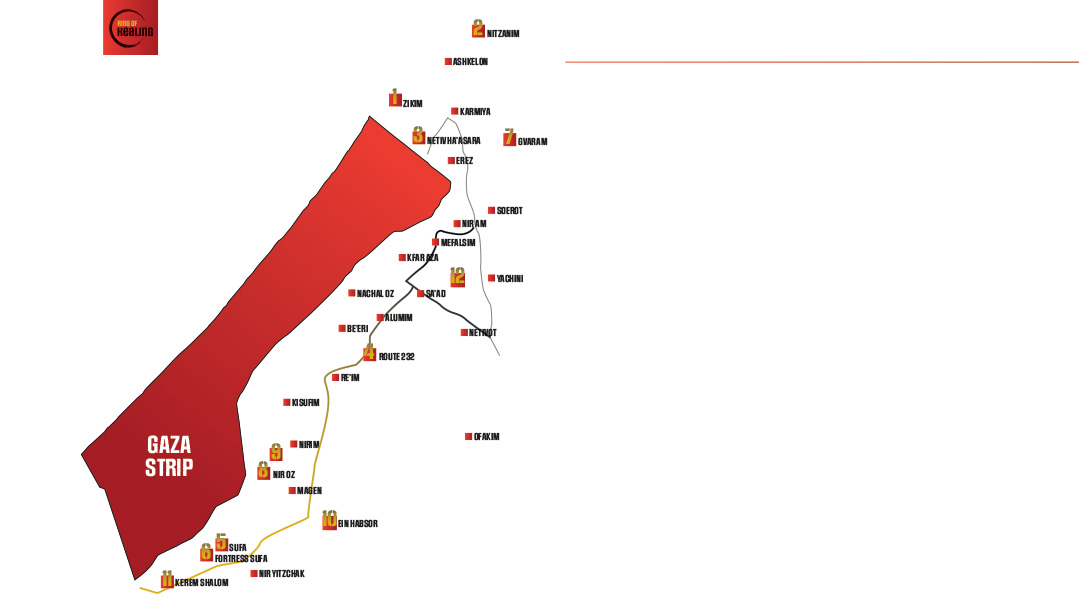

Meir, 67, and his wife, Esther, who live in Kiryat Motzkin, a city near Haifa in northern Israel, are typical mesorati (traditional) Jews. Meir, the grandson of a dayan on the Baba Sali’s beit din, is the semiretired Israel logistics director for Philip Morris, the tobacco company. Asaf Pinchas, the youngest of their seven children and a member of Battalion 77, died in combat in southern Gaza on December 27, 2023. After his death, the Tubuls weren’t interesting in being involved in anything.

“During the first three months, we received invitations to every type of event you can imagine,” Meir says. “As bereaved parents, we were even offered free trips to Cyprus to relax. But do you think my wife or I wanted to go somewhere just to eat and sleep?”

Then, in late June, the Tubuls saw an advertisement for a shabbaton for families of soldiers who fell in the war. For reasons Meir still doesn’t fully understand, they considered such an invitation for the first time since tragedy struck. They rationalized that they could bring the rest of their children, the topics seemed interesting, and they were intrigued by the speaker list, which included the chief rabbi, a journalist, and a bereaved mother.

“In other words, it wasn’t overly religious. If it would have been, I wouldn’t have gone,” says Meir, who was also experiencing an internal spiritual struggle. Before his son’s death, he was a man of faith. He donned tefillin daily, prayed, and went to shul — but losing his son in Gaza made him angry with Hashem.

“I know He exists, but today it’s hard for me to have emunah,” Meir shares.

The Tubuls signed up for the event billed as “Shabbat Koach,” but Meir had no expectations; he thought it would be good for his wife.

“I was certain it wouldn’t change anything for me,” he says.

Then the Tubuls arrived at Jerusalem’s Ramada Hotel, and Meir was blown away. From the get-go, he says, you could tell the whole Shabbos was arranged by someone who really cared. Meir speaks from experience — he himself has arranged several events — and he was curious about the person behind this one. He kept hearing about “Mendy this” and “Mendy that,” and during the Kosel Tunnels tour, Meir sought out this Mendy — Rabbi Mendy Kenig — to thank him and tell him how impressed he was.

Then, in this first encounter, Meir’s inner spiritual turmoil drove him to ask Mendy, “Tell me the truth. Why do you do all this? What’s in it for you?”

U

nder normal circumstances, Rabbi Mendy Kenig, a 34-year-old Biala chassid from Modiin Illit, likely wouldn’t have crossed paths with Meir Tubul.

The concept of “Shabbat Koach” began quite unexpectedly.

Mendy remembers, “One day, a Satmar chassid from the US — who didn’t speak a word of Hebrew but has tremendous ahavas Yisrael and knew that I was involved in helping people who had gone through tragic situations — said to me, ‘I want you to organize a Shabbos for the families of soldiers who have been killed in the war. I’ll pay whatever it costs.’ I didn’t really know how to go about doing such a thing, but I have lots of connections, so we started planning.”

Mendy had no idea where such a Shabbos could take place, or how many would attend. But what he did know was that he needed to keep an open mind and not push people to do anything they weren’t ready for.

The first challenge he faced was making contact with his target audience. Mendy’s circle is naturally more chareidi, and he didn’t know who to speak to or how to reach bereaved families — and even if he did, how to get them to agree to attend an event organized by an unknown name. But Mendy got to work, researching what would be involved to make such a Shabbos a success.

“I figured that while they might not know me, I could invite speakers who they are familiar with, and that’s how I’d get them to come,” he says.

Among those he booked for these events were Chief Rabbi David Lau, known for his dialogue with all sectors of society; journalist and author Sivan Rahav-Meir, who, though religious, is well-known across Israeli society; popular speaker Rabbanit Yemima Mizrahi; and Racheli Fraenkel, an educator whose son Naftali was one of the three boys kidnapped and murdered by Palestinian terrorists in Gush Etzion in 2014. (This proved to be fortuitous for the Tubuls; Meir mentioned a number of times how impactful it was for him to hear her speak.)

Mendy emphasizes that his strategy is not one of kiruv, rather it’s all about the chizuk.

“I was tasked with a mission to make people feel good so they can garner strength in the face of adversity,” he explains. “I don’t care if they wear a kippah, how they dress, or where they come from. That’s why we look for speakers with different styles.”

Mendy had some advertising designed, and while he had no real expectations, he started spreading the word. Surprisingly, just 24 hours after the advertisement was released, the spots for all 40 families — 200 people in all — were filled.

When Meir encountered Mendy in the tunnels and posed his question — “What’s in this for you?” — Mendy looked at him.

“All I want is to be here for whatever you need,” he finally said. “I’m here to give you a hug.”

The chassid from Modiin Illit and the traditionalist from Kiryat Motzkin embraced. They began to talk, sharing their stories and backgrounds — and Mendy, too, has quite a story. (The Kenigs’ oldest daughter has autism; after three daughters, the Kenigs were finally blessed with a son, who also has autism.)

As they spoke, both Mendy and Meir were moved to tears. In fact, Meir is still emotional as he recalls their initial conversation.

“For the first time since my son’s death, I felt that someone was really listening to me,” Meir says gratefully. “It felt genuine. And hearing his story, I couldn’t believe that someone who had been through all this had the strength to keep going.”

S

ix years ago, Mendy was mainly focused on raising his growing family and on his personal growth. He was sitting on a plane to Budapest, Hungary, en route to visit the grave of Rav Shayele Kerestirer, when he received an urgent phone call: “Mendy, you need to come back now! Mendy, you need to come back now!”

His wife and baby had been ejected from a bus that had started to drive while the rear door was still open. The baby miraculously survived unscathed, but his wife was hospitalized with serious injuries. He tried to get off the plane, but it was too late. Once he landed in Hungary, Mendy contacted Rav Elimelech Biderman to ask if he should take the first flight back or if, instead, it would be better to visit Rav Shayele’s tziyun and then return home. Rav Biderman advised him to visit the gravesite, take on a kabbalah, and then get home as quickly as possible.

“I arrived at the tziyun and spent five minutes there. I thought about many things I could take upon myself, but Rav Shayele was a paragon of chesed, so I figured the best thing would be to do something for others, to think of others,” he remembers.

Minutes later, he left and headed back to Israel. When Mendy arrived at Tel Hashomer Hospital, the situation was serious. His wife was recovering slowly from surgery, but that first Friday they were informed that her condition “wasn’t so terrible” and they needed to free up her hospital bed for others.

Returning home under such circumstances is challenging for anyone, but for the Kenigs, it was compounded by issues that made it all the more difficult: Their eldest daughter has autism, and bringing Mrs. Kenig home in the condition she was in would require advance preparation.

“At that moment, I had a flash of inspiration and contacted a hotel in Bnei Brak to book a Shabbos there,” Mendy remembers

Over Shabbos, Bracha Kenig made a comment to her husband that would change both their lives: “Mendy, you really saved me with this.”

Immediately, he understood that this was what he had to do. This was the kabbalah he would take upon himself: helping families going through trauma, allowing them, for a moment, the peace of not having to worry about anything.

The idea that germinated in the Bnei Brak hotel that Shabbos became a concrete reality when Mendy rented a villa in Caesarea in which families undergoing medical treatment could go for rest and pampering, free of charge. The initiative — which expanded into agreements with various hotels for discounted stays — ballooned drastically following the 2021 Meron tragedy on Lag B’omer, when a crowd crush claimed 45 victims. By then, Mendy’s startup had become an organization called Menucha V’Yeshuah, and he understood that the circumstances called for his experience. He organized accommodations and hospitality at a retreat for the families of those who perished.

In Meron, Mendy was approached by a 23-year-old woman who had been widowed by the disaster and was now a single mother of two. After thanking him, she said, “Until now, no one could truly understand what I was going through. But here, I met another woman facing exactly the same situation as I am. For me, that was more valuable than the entire trip.”

Mendy learned something fundamental: Victims of mass tragedies find genuine comfort and solace in groups, surrounded by people who have experienced similar losses. So when he was asked to arrange a Shabbos for families of soldiers who fell in Gaza, Mendy had a good idea of what they would find comforting — and he was right.

In theory, that Shabbat Koach should have been a one-off event, the first and last.

“But feeling that moment, with hundreds of people saying Kaddish together, speaking to each other in a language only they could understand….” Mendy trails off. “There was an energy that made me say, ‘We have to keep this going. I don’t know how, but we have to keep doing this.’ ”

Since then, six more Shabbatot Koach have taken place. More than 350 families —some 2,000 people — have attended. With the help of a small team of chassidim, Mendy brings together hundreds of people from secular and traditional backgrounds for a Shabbos of good food, comfortable accommodations, and speakers and singers. But it’s really more than that — it’s the atmosphere generated by the people themselves: unscripted, informal, a place where each bereaved attendee can feel comfortable sharing with people experiencing something similar, where everyone can find a listening ear, genuine care and empathy, and lots and lots of hugs all around.

Just before his most recent trip to the United States to raise funds for these events, one of Mendy’s daughters asked him not to go — she didn’t like that he spent so much time abroad, away from the family. Her complaint hit him hard. He told her he knew how difficult it was for her, but he asked her to take something into consideration.

“Please understand that right now, there are hundreds of thousands of fathers, brothers, and sons in the army giving everything they have to defend the people of Israel,” he told his daughter. “What I’m doing is the same as what they’re doing, and what we should all be doing — giving the best of ourselves to help Am Yisrael.”

S

ince that first Shabbat Koach, the Kenig and Tubul families have become very close. Meir’s family spent time at the Kenigs’ home. Bracha Kenig and Esther Tubul speak almost weekly, a relationship that has kindled Esther Tubul’s interest in learning more about her faith. While Meir remains more reluctant in this regard, getting to know Mendy has helped him move past many stereotypes of the chareidi world.

“I didn’t even know there were different types of chassidim, distinguished by their clothing,” he notes. “Before that Shabbat, I knew chassidim existed, but I had never had any contact. We never saw what they really are — how deeply they care about the well-being of others.”

In fact, the Israeli press later interviewed Meir about the controversial chareidi draft law, and he pointed out that organizations like Hatzalah, Yad Sarah, or Mendy’s provide services the state should be offering.

“This should be recognized as national service, and those who participate should be exempt from army service, like in Sheirut Leumi (National Service),” Meir announced.

Mendy says that he describes his first meeting with Meir at every gathering he organizes.

“It helps break the ice, bridge the gap. People see me in my black-and-white garb with a shtreimel and assume I’m here to try to make them religious. The message behind my relationship with Meir is simple: All I care about is listening and offering support. Nothing more, nothing less — and every time I finish speaking at a Shabbaton, there’s a line of people waiting to hug me.”

Meir does not gloss over the fact that despite all that his connection with the Kenigs has given him, his relationship with Hashem is complicated right now.

“I’m very angry with G-d. But do you know why? Because I’m sure that G-d exists. I know Him. I love Him. But right now, I’m angry at Him,” he says. “Everything brings back memories. Every time a soldier dies, I can’t help but think about the parents, who are going to get that visit from three men in uniform, bringing them the worst news of their lives.”

He pauses.

“Since the death of Asaf Pinchas, many people have come over to me and said, ‘I don’t know what to say.’ I tell them, ‘Then don’t say anything.’ Mendy understood that from the very beginning,” Meir says. “It’s hard for anyone to truly understand our situation, but at these events, I can look into another father’s eyes and we don’t have to say a word. I know exactly what he’s going through, and he knows what I’m going through. It’s a kind of support that wouldn’t exist otherwise.”

Sometimes, the best thing to do is offer a hug, remain silent, and be a friend. It worked that very first Shabbat Koach, and for Meir and Mendy, it still works today.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1033)

Oops! We could not locate your form.