The Bridge Builder

| September 29, 2020With warmth, charm, and grace, Rebbetzin Chaiky Rubin managed to reach across worlds and foster connection as she brought hundreds of women closer to Torah

Rebbetzin Chaiky Rubin managed to bridge worlds, perhaps partly because she herself represented a fascinating blend of Jewish cultures. Chaiky was raised first in Lakewood, then in Boro Park, and moved to Bat Yam in Eretz Yisrael as a teenager. She was chassidish, with a deep inner spirituality inherited from her father, but as the stylish wife of a dynamic rabbi, she had an open, approachable aura, which helped her touch hearts and bring women closer to their roots.

Chaiky’s father, Rabbi Shlomo Yechiel Grodzinsky, was a true Gerrer chassid. Born in GóraKawalria, the shtetl which gave its name to the chassidus, he was a year younger than the Bais Yisroel and a year older than the Lev Simchah. He treasured his childhood memories of the Sfas Emes, having attended this chassidic giant’s levayah at age six.

The Holocaust robbed Rabbi Grodzinsky of a wife and family, but when he arrived in America, he was determined to rebuild. He married Chaiky’s mother, the daughter of a Rabbi Elimelech Gordon, who had immigrated from Vilna to New York, and sought a genuinely learned and distinguished scholar for his daughter.

The postwar marriage of Gerrer chassid to college graduate and rabbi’s daughter 26 years his junior turned out to be a resounding success. By blending two worlds, and creating an island of Torah and warmth, the Grodzinskys raised a beautiful family.

Movers and Shakers

At first, Rabbi Grodzinsky worked as the shochet in Lakewood. Rav Aharon Kotler would often accept rides in the Grodzinskys’ car, which was the only one in the tiny community. Mrs. Grodzinsky drove, while her husband sat in the back, talking in learning with the Rosh Yeshivah.

When their children grew a little older, they relocated to Boro Park, where there was a Gerrer shtibel, and Chaiky attended Bais Yaakov. Mrs. Grodzinsky worked as a social worker in Maimonides Hospital. Ultimately, though, the idealistic couple decided they wanted to be in Eretz Yisrael. Apartments in most religious areas weren’t within their economic means, but there was a new Bobov kiryah being built in Bat Yam then that was an affordable option, and they settled there.

Young Brooklyn-raised Chaiky learned in the Wolff seminar in Bnei Brak, but she wouldn’t study there for too long. Her aging father who’d lost so much was eager to see nachas, to have his daughter establish a home of her own, and raise another generation to help replace those whom Hitler had eliminated.

Rabbi Yitzchok Reuven Rubin was an American bochur learning in the Bobov yeshivah in Bat Yam when someone proposed a shidduch with the daughter of a local Gerrer chassid. He met Chaiky once, and that was enough for both of them; the shidduch was sealed.

“The shadchan had a daughter who was friends with Chaiky, which was how he knew of her. Years later, I met him and asked what had made him think of our shidduch. He replied ‘You spoke English, and I knew she did too. So, it was a shidduch!’”

Their wonderful marriage lasted almost 55 years before Chaiky was taken from her beloved family from a sudden, fatal brain hemorrhage. The Rav’s respect and admiration for his wife is evident every time he speaks about her.

Dreamer and Doer

The Rubins’ married life began in Crown Heights, where Bobov was based in those days. Two months before Bobov moved to Boro Park, Rabbi Yitzchok Reuven and Chaiky moved too, to 49th Street and 13th Avenue.

“I was a dreamer,” Rabbi Rubin says. His voice is tinged with a tremendous sense of loss. “Chaiky was a doer. She was the facilitator of everything.” Those early years were busy. After a stint as a rebbi in the Chaim Berlin cheder, Rabbi Rubin became menahel of Mesivta Be’er Shmuel of Unsdorf.

His blend of scholarship, charisma, and a natural empathy for people of all types were all standout qualities, but it was his impeccable English that clinched the deal when he became a rabbinical askan. When the Council of Jewish Organizations of Boro Park was founded to represent the community to politicians and the wider world, Rabbi Rubin served as its vice president together with Reb Ephraim Stein of Satmar.

“Most of the rabbanim spoke very little English, so I was a translator,” he says modestly. “But wherever I was, Chaiky remained an anchor. She ensured that we maintained a genuine chassidishe home. Even when we went to Washington for meetings, we went as a couple. Chaiky, who had unbelievable style, unfailingly wore a hat on her sheitel.”

It wasn’t all sweetness and light for the energetic young chassidish pair. They endured tremendous challenges as they tried to build a family because of a diagnosis of Rh incompatibility, which was a major danger at that time. After the birth of their first child, daughter Chani, Chaiky was expecting again. Rh incompatibility put the baby’s life in danger. Their doctor was an expert on this condition, and after receiving four blood transfusions on his first day of life — just as directed by the Bais Yisroel of Gur as soon as he was informed of the simchah — Moshe survived and thrived.

At her next delivery, the midwife gave Chaiky a still, silent bundle to hold. Then, aged just 25, she was told there would be no more children. “She never stopped grieving for this child,” says Rabbi Rubin. “There was always a Yizkor candle lit. And as a rebbetzin, she always reached out to help couples with difficult pregnancies and pregnancy loss.”

When he left Mesivta Be’er Shmuel, Rabbi Rubin opened up a new mosad, a school for children with learning challenges. Forty-five years ago, this was breaking new ground.

“We started the school off in Boro Park. I used to speak things over with the Bobover Rebbe, with Rav Moshe Feinstein, and Rav Shlomo Freifeld, and they advised me to move the school to Flatbush, to get out of people’s way a little. So we bought premises on Bedford Avenue for the school, and soon, we had a shul there too.” The shul drew a steady group of locals, and young Chaiky became a rebbetzin. “It was sort of against her will,” the Rav describes.

Onward and Upward

The special-needs yeshivah was before its time. It didn’t have widespread support, and the logistics of caring for the children and the burden of debt from paying its staff were simply too much for one man. After five years, Rabbi Rubin was compelled to give up his fledgling institution.

It was the Lev Simchah of Gur who saw that he couldn’t take it anymore and advised him to move on, while leaving the school in good hands. In a phone conversation, the Lev Simchah mentioned “Nu, di kimst doch kein Eretz Yisrael — You’re anyway moving to Eretz Yisrael.”

Ever the loyal chassidiste, Chaiky immediately began to pack. “Not easy!” exclaims her husband, all these years later. “She went from 13 rooms in Flatbush to three rooms in the Gur enclave of Chatzor Haglilit.”

In this small, insular chassidish community, a world away from Brooklyn, Chaiky soon adjusted and found opportunities to use her innate gifts to give to others. The Israeli Rabbinate had a monopoly on marriage ceremonies in Israel, and one of the conditions of marriage registration was for the new couple to take a basic course in taharas hamishpachah.

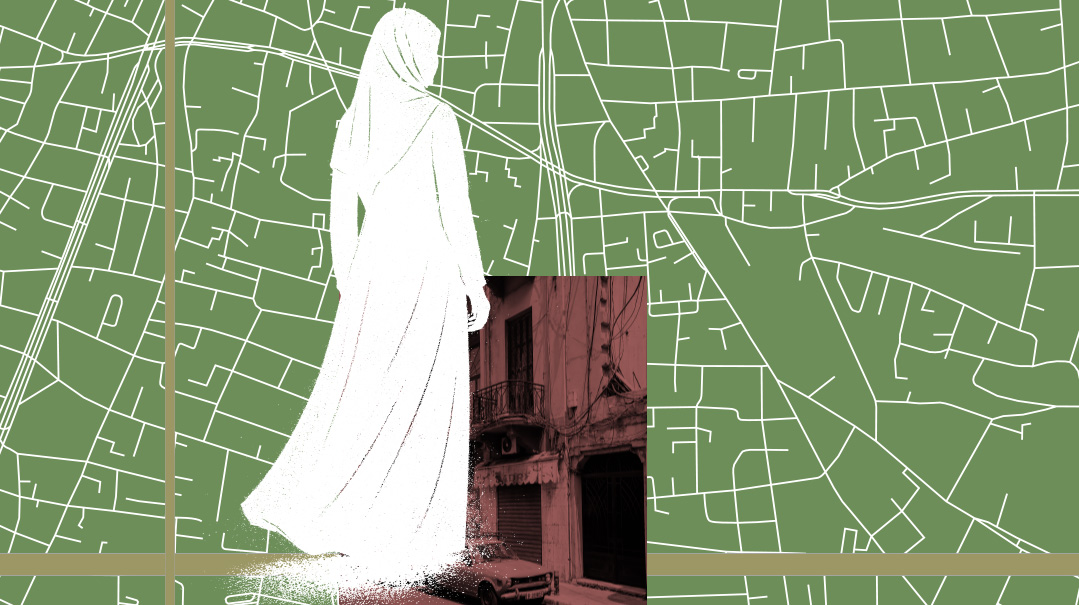

It was in Chatzor, as a Rabbinate-endorsed instructor, that Chaiky first taught kallahs. They were women of all backgrounds whom she successfully reached out to with warmth and understanding to deliver the essential messages that would ensure the purity of their future families. They listened to the young American’s guidance and shared their own brand of hoopla and celebration with her. “She had great adventures with her ladies,” is how the Rabbi puts it.

Chatzor is located in the rolling hills of the Galil, near Tzfas. “At the time, there was no heimish chevra kaddisha in Tzfas,” says Rabbi Rubin. “The chassidish community there was just starting, and as everybody knows ‘young people don’t die,’ so they didn’t have a group. When someone was niftar, they had to call the Gur community in Chatzor for volunteers.

“My wife took five ladies with her and went to do that taharah in Tzfas. She then taught local ladies how to do this chesed shel emes correctly, as she’d been a chevra kaddisha volunteer for the Bobov community in Boro Park.”

On the Move Again

One day, in conversation once again with the Lev Simchah, Rabbi Rubin received his marching orders to go back to rabbanus. “Vos tit ir du?” the Rebbe asked. [What are you doing here? You should be serving as a rav].

Providentially, that weekend the Rubins were perusing the Jerusalem Post, when they saw an advertisement from the South Manchester community seeking to appoint a new rabbi.

They had no idea where South Manchester was and no concept of what English Orthodoxy was (“I thought maybe it was like Young Israel,” the Rabbi admits), but the ad came on the heels of the Rebbe’s directive, and that was what mattered. Sending a résumé was the next step, and when the congregation hired the American-Israeli Gerrer chassidim as their next rabbinical couple, the Rubin family packed up once again and moved.

“I was raised in Brooklyn and then spent a great year in the Manchester Old Sem,” says their daughter, Chani Schreibhand. “I’d loved Manchester, so moving there sounded okay. North or South meant nothing to me.”

They arrived to a packed synagogue. “A hundred thousand spiritual miles away” from North Manchester’s heimish community, the South Manchester shul was peopled by high court judges and senior doctors — the upper-class anglicized Jewish intelligentsia. The Rubins were in for a shock when they realized that there were only three shomer Shabbos families in the entire community.

“I gave a derashah, and they hired us. I didn’t know no one was shomer Shabbos. I just didn’t know,” Rabbi Rubin says with wonder. Being American, he was unaware of a situation fairly common in the UK — a “united synagogue” traditional Orthodox shul, with congregants varying from fully to minimally Jewishly observant. “I still don’t know what they were thinking when they hired us.”

It was a world where Yiddishkeit wasn’t black and white, and the new couple had to develop tolerance and accept these Jews where they were.

Despite the cultural gap, despite their differences, the Rubins stayed with the South Manchester shul for 25 years. Rabbi Rubin lays all the credit at his wife’s door. She was elegant, poised, full of warmth, and had a tremendous flair for fashion. “My Chaiky became a superstar. The entire shul waited for her entry on Shabbos morning to see what she was wearing. She started a bat chayil ceremony with the 12-year-old girls, and bonded with them over a specially developed course of study. At the end, she invited the mothers to come along to view the mikveh. She created a tefillah for the ceremony, which the girls said together with their mothers.

“She did it with such style that these mothers — judges, lawyers, high-born Anglo ladies all — put their hands on their daughters’ heads and cried with emotion as they recited a short prayer Chaiky had composed.”

Back in the Flatbush days, Chaiky Rubin had injured her back. As part of her recovery, she trained as an exercise and ballet teacher, which became a secondary vocation. When the family moved to South Manchester, Chaiky couldn’t see herself spending the whole day in her new, gentrified surroundings. She soon met and connected with some frum North Manchester ladies, got a driving license, and began to drive for over an hour each day to give her Keep Fit classes.

“My son went away to yeshivah, and our daughter was married to Reb Yitzchok Dov Schreibhand, a respected sofer, so this let Chaiky build an environment of her own, outside of our community,” the Rabbi explains.

The classes were a runaway success in the tight-knit community. For over three decades, until the bleak day of her hemorrhage, Rebbetzin Chaiky Rubin became known for her role as the Keep Fit teacher. She had a brachah from the Pnei Menachem of Gur to be matzliach in helping women in both ruchniyus and gashmiyus. In addition, the Manchester Rosh Yeshivah, Rav Yehuda Zev Segal ztz”l, praised her efforts to help women’s health and personally phoned her to insist that she keep up the classes and wish her success.

Along with the floor exercises and stretches, the women who attended her classes had the opportunity to socialize with friends and share life with a wise, though “normal-like-you” rebbetzin.

“She talked her ladies through all kinds of stuff,” Rabbi Rubin explains. “If one of Chaiky’s ladies called, I would leave the room, because it was likely to be personal. Chaiky carried everything so discreetly. She wouldn’t go away and miss classes, so we had to plan vacations at exactly the same time as most of the North Manchester community.”

When the couple arrived, the South Manchester synagogue was located in the Fallowfield area, which was mainly populated by students at the local university. The shul members, meanwhile, had moved further out into the suburbs, and were driving to shul every Shabbos. The Rubins began to reach out to the local Jewish students, but at the same time, they were deeply pained that most members of their “Orthodox” community drove to shul on Shabbos.

Upon his leave-taking from the Lev Simchah, Rabbi Rubin had received advice to lead with “savlonus — patience.” So he bided his time, building up a relationship with his congregants, gently showing them the warmth of genuine Yiddishkeit. “Then it was time. After ten years, I told the machers that it was enough. ‘Either you build a shul in the suburbs where you live so that we can be a real Orthodox shul, or I’m leaving.’ ”

They chose to build a beautiful new synagogue in an area called Bowden. The Rubins moved over and began a new chapter.

Fusing Connections

Chaiky, at first an outsider, built bridges. At a very early Shabbos meal hosted by a community member, the hostess told her she was using the wrong piece of silverware for one course. She immediately bought a book about how to set a table like English royalty. She was immaculately dressed, combining fashion with impeccable standards of tzniyus, and the community members looked up to her. When some well-connected members arranged for His Royal Highness Prince Charles to open their new shul, he naturally chatted to their rebbetzin. Her job included teaching the brides who would be married at the South Manchester synagogue.

“There were around 200 couples she taught over the years,” the rabbi estimates. “Some were more traditional, others barely knew they were Jewish. The rebbetzin reached out to each lady, opened a conversation, and taught her about a Jewish marriage. She managed to do a tremendous job.”

Anne Lopian, a close friend of Chaiky’s, says that teaching about a Jewish marriage was one of the rebbetzin’s greatest strengths. “She spoke to women who didn’t know anything and set them on the right path in marriage, making it into a very beautiful, spiritual experience. There were so many women whom she influenced, both first and second-time kallahs.”

The Rubins were outstanding in their care for sick community members. Chaiky’s natural empathy was her ticket to success. Rabbi Rubin was the chaplain at Christie’s Cancer Hospital in Manchester, a world-famous cancer center, so Chaiky often visited there, offering encouragement. If a patient was up to it, she spoke to them about spirituality and said Tehillim with them.

On one occasion, she visited a secular woman who was crying, very distressed that she’d lost her hair due to chemotherapy. She was wearing a cloth head covering supplied by the hospital. The Rebbetzin didn’t hesitate. In the face of the lady’s pain, she removed her own wig and combed it on the patient’s head. She left the hospital wearing the cheap fabric turban; her own well-cut sheitel a gift to console the cancer patient. “I guess I wasn’t home when the rebbetzin came home, because I didn’t even know about this story until someone came in and told us at the shivah,” says the Rav. “She got away with it.”

Rebbetzin Rubin accomplished much for taharas hamishpachah not by giving public lectures but by networking with individuals, sometimes enlisting one woman to speak to her friend, so necessary knowledge about the mitzvah was passed on with discretion, with tzniyus, and with tact. When it came to kallahs, she went all out. She deployed charm and style to make the mitzvos appeal to the secular young career women whom she dealt with.

The Rabbi recalls some heartrending instances of illness and death in the community and the rebbetzin’s innate understanding of how to comfort both the patient and their families. “As a rav, I had to go to be with people. Sometimes, they were more ‘there’ than ‘here,’ and their families had already gathered. I can remember some instances where the patient’s face showed fear and anxiety and Chaiky knew what to say or what to do, which calmed them.”

After 25 years as rabbi and rebbetzin of South Manchester, the Rubins “retired” to lead a shul named Aish Kodesh in North Manchester. Rabbi Rubin is active in rabbanus, counseling, and is a popular weekly columnist at the Jewish Tribune. The Rebbetzin was ever in demand, active both as a kallah teacher — frum-from-birth girls loved her approach too — and a Keep Fit instructor.

This new chapter brought together the strands of her life as a wife and rebbetzin; Chaiky brought so much to her new kehillah and to all “her girls” of the Keep Fit world. Above all, she kvelled over three generations of her chassidishe family.

Their marriage was a close one, and a priority for both. Chani Schreibhand points out that with the two children long married, her parents spent lots of time together as a couple.

“They lived through so much together and worked on their marriage. When I went to visit on a Shabbos, my parents were always sitting at a perfectly laid table — my mother went the whole nine yards for Shabbos, every single week, with her salads in crystal bowls and her table set from Thursday — and my father would say a long devar Torah, to an audience of one, because my mother requested it.”

In 1999, their son, Rabbi Moshe Rubin, moved to Glasgow, Scotland, where he’s rabbi of Scotland’s most active community. Like his father, Rabbi Moshe is a Gerrer chassid in full regalia, but also like his father, his warmth and approachability make him a leader of people from a very different Jewish background.

“Our being chassidish did not impact our community,” explains Rabbi Rubin senior. “I never pushed it on anyone. We’re all Jews, and it was about reaching their neshamos. As the only chassidishe Yid in Scotland, my son has the same view.”

The Rubins were once guests at a shabbaton in Yerushalayim which included families from South Manchester and from their son’s community in Glasgow. “The rebbetzin was like a cheerleader. On Sunday, the women went on a bus to Kever Rochel. Chaiky had a big thing going with Mamme Rochel, so on the way, she prepared the women, singing a poem to them about the connection to Mamme Rochel. She spoke their language, she spoke on their level, and they were drawn to her. They asked her about cooking, relationships, everything.”

Chani says that her mother’s ability to reach people was born of a personality overflowing with empathy for others. “My mother and I used to go out on Friday mornings, to catch up and spend some time together, as we both worked during the week. I remember that a hotel doorman asked her ‘How are you, Mrs. Rubin?’ and she asked him how he was too. I also said hello, and I was about to continue walking, when my mother asked him why he looked so down today, and what was wrong… Of course, he told her his tale of woe. Everyone did.”

The rav shares one final story.

“The president of the South Manchester shul, a traditional Jewish fellow who received a knighthood for being chairman of the British Medical Council, had a son living in Karmiel.

“He once spent a Shabbos in Yerushalayim with his son, and when he returned, he told me that he’d been at the Kosel on Friday night, and they sang a gorgeous song, maybe we could sing it in our shul. I was a bit wary, but when I asked him to sing it, the song turned out to be ‘Yedid Nefesh.’

“Now, my shul was Ashkenaz, they didn’t say ‘Yedid Nefesh,’ but as a chassid, I used to say it to myself before Erev Shabbos Minchah. So, the president wanted to sing ‘Yedid Nefesh,’ gevaldig, it was a win-win.

“I pointed out to him that the words were not in the Singer’s Prayer Book which all real English shuls use, so he arranged for a big plaque with the words to be hung in the shul. It became his niggun.

“Later, when this man became very sick with a brain tumor, I was called over as his family was gathered around at his bedside. I could see he was almost a goseis, and I could also see fear, pain, and anxiety on his face. The rebbetzin came to the house, she took one look, and she told me to start singing ‘Yedid Nefesh.’ The patient calmed down, the agony left his face, we sang to him, and he was niftar five minutes later.

“A day after the Rebbetzin’s hemorrhage, when we were gathered in the hospital and things were coming to an end, we began to sing all the niggunim she liked. The last thing we sang was ‘Yedid Nefesh.’ I saw the pattern of her breathing change — and then she passed away.”

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 712)

Oops! We could not locate your form.