The Bricks That Build Us

Peshi Haas’s portraits capture a family’s memories

Every artist has a niche, and for Peshi Hass, it’s her ability to resurrect memories on canvas. She can take an edifice of brick and stone and paint it in a way that reveals the inner essence of the structure, capturing the memories of those who spent time there.

Like the painting she made as a memento for her father, of a building on Madison and 25th in NYC, once home to the family business started by her grandparents shortly after they came to the United States from Europe following World War II.

Fifteen years ago, in that very building, Peshi started out as a budding artist, working in a studio just a door away from her grandmother’s office.

Every morning, Peshi would take the train from her home in Lawrence to Manhattan. It was a long trip, made doubly hard because she had two small children at home. Her grandmother never missed a day of work, and could be found each day at her desk, reviewing paperwork. She appreciated anyone with a vision and a dream and she’d stop into Peshi’s studio every day to see what her granddaughter was working on.

Peshi painted in a red, paint-smeared apron, and her grandmother focused all her pride on that apron, perhaps seeing it as a symbol of Peshi’s hard work. Dein shirtzel, she’d say, using the Yiddish word for apron.

“Maybe I reminded her of herself,” Peshi says, “although she worked way harder than me. I don’t know how she overcame so many obstacles.”

The painting Peshi made of that building on 25th and Madison isn’t just beautiful — it also captured the family’s personal memories of the past.

Paint Running in Her Veins

Peshi’s talent is in her blood: her grandmother would paint decorative objects and sell them, and her aunt is a published art historian. Peshi always loved to draw; it was her “main attribute growing up.” She remembers her ninth-grade art teacher, an exacting woman who noticed her talent, and encouraged her.

“She was very strict and tough,” Peshi recalls. “My classmates were really annoyed. They said art is where we go to chill. I didn’t say anything, but I secretly loved that class. It was my time to shine, and my art teacher noticed I was artistic the first day. She said, ‘You’re good with your hands. Don’t stop what you’re doing.’ ”

Her love of drawing led her to pursue a degree in marketing, which could have been a good choice — but it wasn’t where her passion was. Peshi wanted a career in the fine arts. With her husband’s encouragement, she applied to several art programs, and was accepted to the school of her choice.

“People say an artist doesn’t need to go to art school, that if you have the talent, it’s innate,” says Peshi. “But while I did come in with talent, you can’t compare to what I left with. The skill and the education I got was priceless. It molded me to pursue a career in fine arts, rather than just teaching art or pursuing graphic design or interior design.”

It was an intense four years. The college is a liberal arts school, with an avant-garde program, and it was a culture shock.

“It was hard for a 19-year-old to witness,” she says. “The first day of art school, I called my husband crying, and said, I think I have to leave. I can’t do this. He told me, ‘If you leave today, you’ll never go back. So think. Do you want to leave or pursue your dream? It’ll be hard but you’ll be able to do it.’ ”

There were many challenges. Aside from the intensity of the program — multiple projects were due weekly — the school had a strict attendance policy, and Yom Tov was hard to explain.

“They did not understand that Succos and Pesach are a whole week,” she said. “They think of the Seder, or Yom Kippur. They don’t believe you that there are other holidays.”

She also gave birth to her first two children during her time at school. But perhaps hardest of all was that she was the only frum girl in the program, and it was a lonely experience. Things got easier in her fourth year when she took a class with a frum instructor.

“I finally felt some comradery,” she says. “But for four years I had lunch breaks on my own, walking the streets of Chelsea on my own.”

Stories Everywhere

These days, Peshi’s studio still shares space with the family’s offices, but they’re in Lawrence, where she lives, and the commute is easier. On an unseasonably warm winter day, I visit Peshi’s studio, and she shows me around.

Her art hangs on the walls of the office where her father and brothers work. At one spot, to get a closer look of a painting, I step over some boxes of serving spoons and cutlery. Jay Imports, the family’s business, sells everything tabletop related.

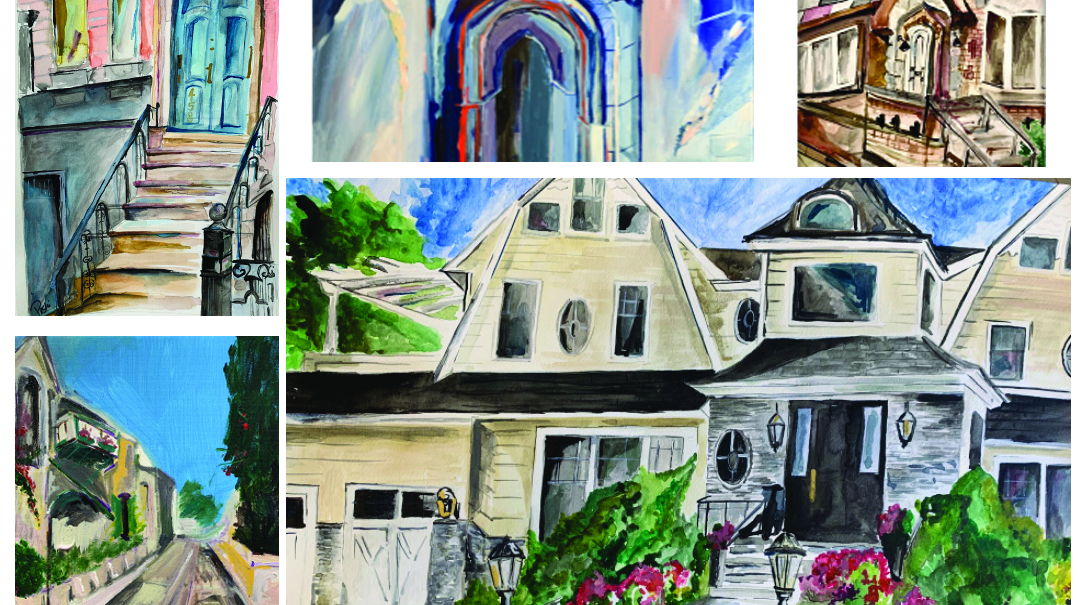

Peshi is drawn to architecture and city scenes, and there are paintings of streets in Paris, Rome, Prague, New York, and studies of arches and doorways. Her painting style is modern, whimsical, and although she paints buildings and streets, there’s movement on the canvases.

But it’s in memory, roots, and history where she draws her inspiration. “I’m nostalgic and sentimental — I always reflect, look back, and revisit the past,” says Peshi.

With soft paint strokes and vibrant spots of color, Peshi’s paintings aim to capture both moment and mood; the canvases are like a snapshot of a memory. Her Kristallnacht series was inspired by her grandfather’s experiences prior to World War II. A while back, she painted the town square of Sanok, her grandmother’s Polish hometown.

“There’s a story everywhere,” she says. “When it comes to my work, it has to be meaningful or I don’t think it’s purposeful.”

Peshi’s studio is flooded with light. There are canvases everywhere: almost every inch of wall is covered. Some canvases are on easels, prepped for adjustments, charcoal sketches lay fanned on the floor in a corner. A white drafting table is at center; the paint-splattered red apron is draped over a chair.

I notice a large painting of vibrant carousel, boats visible in the background, inspired by a trip to Monte Carlo she took with her husband.

“The waters, the cityscapes, the ancient cities were really magnificent,” she remembers. “What surprised my husband was that we thought we were going somewhere that had nothing Jewish to it, but there was a bit of Jewish history. Our first day there, my husband found a Safra shul that was just built, and he had minyanim. A beautiful new shul in Monte Carlo — who would imagine?”

What Homes Hold

Peshi feels instinctively that a place is more than just a place, that locations have meaning to people, and memories link past and present. This struck a chord within her early last spring at the start of the pandemic, when neighbors rushed their son’s wedding in order to make it before the country shut down. Peshi joined friends and family gathered outside the family’s home, participating in the simchah from a distance.

“When the chassan left his home, he was greeted by his aunts, uncles, cousins, and neighbors, standing in front of their cars, some with music on loudspeakers,” she recalls. “He walked out to siman tov u’mazal tov, and his home was in the backdrop of this beautiful scene; it was the start of his simchah.”

It was somewhat solemn, she says, but also beautiful. The symbolism of a chassan leaving home to start his own home spoke to something in her. Always drawn to the memorable, Peshi wondered about “niching down,” to create personally meaningful art.

Instead of painting a street, a cityscape, or an iconic building, she thought, what if I could individualize by focusing on the family and their memories by painting their home. This was the catalyst of her current project, The Bricks That Build Us™.

When she captures a home on canvas, she gives a person a portal to walk through to access memories of the past. “Some houses look more beautiful than others,” says Peshi, “but it’s not about the beauty. It’s about the memories, the stories — the hard ones and the happy ones.”

After her neighbor’s wedding, Peshi painted their home, focusing on the happiness of the occasion, and filtering out the pandemic’s tension. Seeing the painting, the mother of the chassan was struck by how Peshi had captured all the joy they’d had in their home into the painting. It was restorative for her. “You made it how it was, the way it was before,” she told Peshi.

Shortly after, the project became personal. When COVID hit, Peshi’s parents were out of state, and planned to stay away from New York until things calmed down. Missing her parents, she decided to paint her childhood home as a gift for her mother.

“I sent the painting to my mom on Mother’s Day,” says Peshi. “I have so much hakoras hatov to my parents for my happy upbringing. When I went to the airport to pick my parents up in June, my mother had brought it home in her carry-on. We went to frame it together.

“My parents don’t live in that house anymore,” she continues. “I never thought my parents would move. When they did, they asked us to come pack up our rooms. I couldn’t; I was afraid I’d cry. I told my mother to just do it without me. When I painted their house, that’s when I said my goodbye.”

The Bricks That Build Us™ isn’t for everyone, says Peshi — not everyone had a charmed childhood. “I thought of it for people whose parents moved out of the home where the children grew up. I have that in mind. We no longer live with our family of origin, but here’s a way we can remember, a way to thank our parents for our childhood.”

From Memory to Medium

Painting a house as it appears in the memory of another requires careful listening. Clients share details, vignettes, and Peshi listens for the nuance and the emotion in the stories.

People want the painting as a keeper of memories, a reminder of who they used to be, and as a tool to help them share those memories with younger generations. Because houses often change with time, clients are particular, and specify what they want included or ignored, so that the result is an accurate reflection of their memory.

“People give me a list,” says Peshi. “Everyone wants the house number, one client wanted the station wagon in the driveway, another wanted their pergola.”

The process becomes more meaningful when clients share the stories behind the details. One client, who wanted a painting of her childhood home, was insistent a small brick wall, no longer in existence, be included.

“That’s where she used to play Shabbos afternoon with her siblings,” says Peshi. “They’d perform mini concerts, plays, and skits on this brick wall, and afterwards, she and her siblings would all line up together, hold hands, and jump off, like it was a stage. We had to place it there so they’d remember those Shabbos afternoons from long ago.”

Another client, who’d grown up in a blended family, had fond memories of the stoop outside her home, where she’d wait with her half siblings each morning for their school buses. “The children all went to different schools. Some siblings went to day schools; some went to more yeshivish schools. They were all one family, but they were dispersing every morning to different parts of the neighborhood. She remembers waiting together in the morning, then spreading out, and then coming back home to that same stoop.”

After speaking with clients, Peshi visits the house herself, when possible, photographing it from all angles, noting architectural details, and features such as walkways and driveways. There are details she can pick up that the client didn’t communicate.

There was the client who had a houseful of boys, and no daughters. When Peshi came to photograph the scene, there were bikes, scooters, and helmets scattered in the driveway and the front lawn.

“I took the photos without moving anything, thinking I’ll clean it up when I do the drawing,” Peshi recalls. “Yet when I started to paint, I wanted to include the bikes, because I felt it was symbolic of a cheerful, happy home. But she just wanted the painting of a beautiful home. So, we included happy flowers, and made the house very bright. I used that to portray the exuberance of the home.”

It’s not always possible to visit the home; some are too far or out of the country, and COVID travel restrictions complicate matters further. One client wanted a painting of the cottage where she spent summers with her extended family. It was out of the United States, so she sent drone photos of the property, showing the house from all angles.

“When I spoke to her I was able to hear her longing and how much she missed her family,” Peshi says. “It was a cottage where four generations summered together for decades, but because of the pandemic, the family wasn’t able to get together this summer. One of the children gifted this painting to the matriarch and patriarch of the family to show hakoras hatov and love, and to commemorate her memories of their summers together.”

Stages of a Painting

When she has the photographs, Peshi does initial drawings in charcoal. They resemble architect renderings, and often, they’re abstract and lack details, but they help with layout and composition.

Clients will choose their medium, either acrylic or watercolor. Acrylic produces tighter painting, most clients choose watercolor opting for looser composition, something more dreamy and reflective of their memories. Watercolor is the medium Peshi began using during the pandemic, when she was working from home, and needed a more compact medium.

Although her style is impressionistic, she keep the homes in their true colors. She uses pastels skillfully, avoiding their trap of weakness; there is a full-bodied robustness to her colors, capturing the personality and atmosphere of the home. Though buildings are immobile, there’s life and movement in the painting — the lives lived in the home show on the face of the house. She’s less concerned with the rigid accuracy of the space, and more concerned with truth, with the inner essence of a place, and how it feels to people.

It can take 15 hours to paint one piece, and she needs time between sessions to assess and make adjustments. With acrylic, which is painted on an easel, she can walk back in order to assess and gain perspective. Watercolor is painted taped to a flat surface so the paint doesn’t drip. To get the perspective to make adjustments, she photographs them to look at later.

“I’ll see what needs fixing — maybe a pop of color, widening a road, adding equilibrium,” says Peshi.

She always starts by painting the house and fills the surrounding details later, except for the client who had strong memories of the garden of her mother’s home. She remembered the pride her mother took in that garden. For that painting, Peshi painted the garden first.

“She’d call and ask me, are you including the garden?” Peshi remembers. “Her mother spent so many of the days of summer toiling over the garden. I worked hard on that garden.”

There are challenges to portraying a home with lots of history. If any detail is inaccurate or the aura is off, someone will be unhappy. It requires presence of mind to simultaneously hold both her own and the client’s impressions as she paints, sifting through countless emotions, and maintain delicate balance.

When a painting is completed, she sends a picture, waiting for confirmation that she got it right, which she inevitably does. Clients will call saying how many memories she conjured up, and how well she caught their homes on canvas.

“You got our swing,” said one client, referencing the swing on their front porch. “When we sit on it now, we’ll think of the painting of our home.”

She acknowledges that we’re all in temporary homes now, but her intentions are to capture memories. She takes a family’s personal story, and makes it into a piece of art that’s personal and meaningful, a catalyst for memories and reflection. As someone who always looks back and reminisces, she takes joy when her art helps people do the same.

Samuel Morse first created the genre of self-aware art when he painted Gallery at the Louvre, a painting of a room that went on to be displayed in that very room. Peshi Haas provides her own interpretation of the self-aware in The Bricks that Builds Us™. Her paintings of family homes, symbolic of the family’s memories, are meant to be hung within the homes of those very same families. They offer a window to the past as the family continues to build more memories in the present.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 731)

Oops! We could not locate your form.