The Blame Game

| August 22, 2007It seems to come as naturally to Jewish women as gefilte fish and chicken soup. But unlike gefilte fish and chicken soup, guilt isn’t always wholesome or appetizing. How to distinguish between constructive and destructive guilt

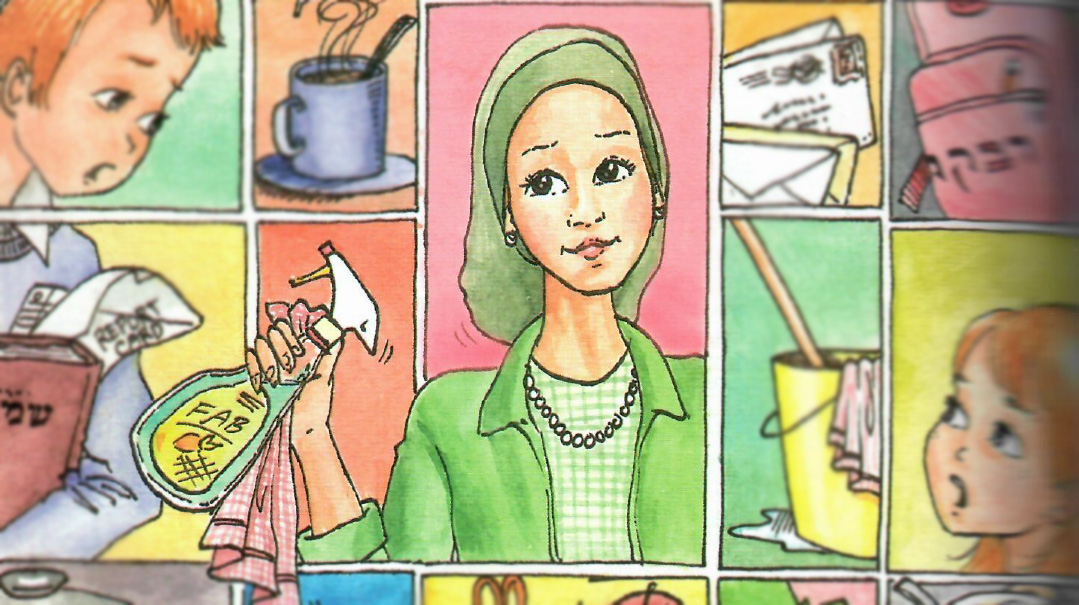

Is there such a thing as a Jewish woman without guilt? Seemingly not. The possibilities are endless: If we’re cooking, we can feel guilty that we’re not playing with the children. If we’re playing with the children, we can feel guilty that we’re not cleaning up. If we’re cleaning up, we can feel guilty that we’re not out doing chesed. If we’re out doing chesed, we can feel guilty that we’re not home cooking.

As Shoshana Siegelman, social worker and teacher, of Kesher Counseling, points out, women are particularly challenged in this area, because there’s no inherent limit to our job. We can never feel “finished,” since there’s always more we can do: for our children, for our homes, for our communities, and for our own spirituality.

Guilt can be debilitating. On the other hand, as Rabbi Emanuel Feldman has put it, a “guilt-edged conscience” can be a positive and powerful tool for growth. How can we differentiate between the two types of guilt? And once we do, how can we conquer the negative type?

A Working Definition

When I called Shalom Francis, LCSW, to ask my questions about guilt, he asked, “How do you define guilt?”

I was stymied. Guilt is … well, guilt is a feeling, I thought. Can it actually be defined? Unable to respond, I resorted to the journalist’s old trick; I turned the question back around to him. “How would you define guilt?” I asked.

His answer was swift and unhesitating. “Healthy guilt is the perception that ‘I have a flaw.’ Unhealthy guilt is the perception that ‘I am a flaw.’”

The difference between these two perceptions is vast. Someone who has a fault, a character flaw, can accept that this is the case and work on that fault. But someone who sees himself as intrinsically flawed ends up feeling discouraged, or despairing. He sees no reason to work on something that is an inescapable part of his makeup.

Francis compares this to two cars. One is an old, beat-up clunker. The other is spanking new, right off the showroom floor. If both cars got a scratch, which car would you be more likely to fix? Although logic would dictate that an old car requires much more work than a new one, most of us would say, “Why bother fixing an old car that will never amount to much? I’d much rather fix the new one; once I get this scratch out, it will be perfect.”

Each of us is a Divine creation, a neshamah tehorah, a pure soul. Remove the layers of sin, and the shining, pristine soul reappears in all its glory. Our mission in rectifying our misdeeds is to remove the blemishes from that which is innately beautiful. The trouble arises when we fail to see ourselves as innately beautiful, when we perceive ourselves as beat-up clunkers, unworthy of repair.

In Shoshana Siegelman’s words: “We each have a pure neshamah. And then there is the yetzer hara. We need to differentiate between the two; I made a mistake but I am not my mistake.”

Useful guilt is the start of the teshuvah process: We acknowledge our misdeed, regret it, confess it, and undertake to change. Negative guilt, on the other hand, is an addictive pull which doesn’t let up. Obsessing over the problem doesn’t allow us to work to correct it. Rather, it leads to depression and defensiveness.

Should’ve, Could’ve, Would’ve …

“There are two ways that the yetzer hara loves to work on us,” Shelly Presby, LCSW, comments. “Either it persuades us to think: ‘It’s everyone else’s fault. Poor me. I’m helpless to change the situation,’ or it persuades us to think: ‘It’s all my fault. I’m not good enough. So why bother to try to change?’”

In Presby’s terms, guilt and blame occur when our mental picture of life as it should be doesn’t match the reality of life as it is. “Life never matches that perfect vision,” Presby says simply. In her Highland Park, Chicago practice, she has dealt with hundreds of clients trying to adjust to life’s realities. Many parents live with a never-ending inner refrain of: “Should’ve, could’ve, would’ve … ” Should’ve caught the learning disability before it developed into a major problem. Could’ve detected the illness while it was still in its early stages. How could I not have seen it? What kind of mother am I?

Presby also sees a great deal of guilt in people torn between the conflicting needs of their parents, in-laws, and spouse. If the parent-child relationship was complicated to begin with, the problem is aggravated. In that situation, the grown-up children must also contend with guilt about their hidden resentment towards their parents. Children who grew up hearing, “Bad girl!” carry that voice through to adulthood, ringing in their ears.

“All of this leads to a lot of depression and hopelessness,” Presby states. The never-ending sadness leads to feelings of helplessness and to passivity.

She uses two components in her approach to working with this sort of problem. One is to help people to see the bigger picture: the fact that, instead of “could’ve,” perhaps they could not have done better. Hashem is the One Who sets up our challenges; we cannot get around them or deflect them. It might not be possible to be at the Chumash party and at work at the same time; we cannot always satisfy all of the people in our lives.

The second component is to help people come to terms with that yetzer hara/yetzer tov dichotomy. We need to identify within ourselves that those debilitating guilt feelings are the product of the yetzer hara.

“When I sit down with a client, I tell her, ‘There are really four people sitting here: The ‘big’ Shelly Presby, the ‘little’ Shelly Presby, the ‘big’ you, and the ‘little’ you. The child in us is a welter of illogical emotions, resentments, and unfulfilled expectations. Our challenge, the work of a lifetime, is to help the mature, rational self, the yetzer tov, to gain the upper hand. We’re here to actualize our potential, not an easy task. It may take 120 years to perfect ourselves.’

“I tell clients, ‘You’re going to make mistakes. But with work, you’ll get there.’ Many clients who originally had felt helpless have ‘gotten there’ already; they’ve grown in many positive ways through having worked on their issues.”

The Dancers

Life with guilt is difficult. Shalom Francis poignantly describes the struggles of desperate “people-pleasers” who are doomed to failure. Paralyzed by guilt and inadequacy, they spend an inordinate amount of time and effort trying to hide their self-perceived flaws behind a veneer of perfection.

“I call these people ‘dancers,’” Francis says. “They’re afraid of confrontation. They always want to make everybody happy, and are always dancing to the other person’s tune. The trouble hits when, usually after marriage, they’re caught between the desires of two or more people. Hard as they try, they can’t dance two different dances at once.”

People plagued by guilt are constantly reading the emotional landscape, searching for where they might be criticized and who might criticize them. Always expecting to be blamed, they create excuses for things that could never be considered their fault. They’re terrified of being wrong, and will either decline to offer an opinion or will offer an opinion and then worry obsessively about how it was received, and what they should have said instead.

With the addition of a spouse and children, the quest for a facade of perfection becomes more and more difficult. The impossible goal of maintaining a perfect image for them is an exhausting exercise in futility.

Overwhelmed by internal pressure, the person who is plagued by guilt may “let off steam” with angry outbursts in other areas of life. Even innocuous comments can generate a furious response, if they come too close to the source of hidden guilt and shame.

For someone who’s afraid to face his faults and may be in complete denial that they exist, is there any way out of this unhealthy guilt?

“Lev yodei’a maras nafsho, the heart knows the soul’s bitterness,” Francis quotes. “When someone walks into my office, he generally knows, deep down, the source of his problem.” The challenge is to help the person feel safe enough to acknowledge the problems. “The key is for him to accept that he’s human, and that he’s allowed to make mistakes,” Francis continues. “It’s all about growth: accepting the problem, confronting it, and dealing with it.”

Each person needs to identify: What function does my guilt play? Is it spurring me on to further growth or is it holding me back? In Francis’s view, this is a major purpose of charatah, the remorse that’s essential to the teshuvah process. Remorse is a strong imagery of how awful the misdeed feels, a powerful mental picture that causes us to equate the wrongdoing with instinctive revulsion. The purpose of this image is not to cause us to wallow in the misery of the past, but to prevent us from repeating our mistakes in the future.

Francis quotes Rabbi Yaakov Meir Schechter: “The only thing we have to work with, really, is the present. So the yetzer hara tries very hard to keep us out of the present. Either he fixates us on the past, through guilt and depression, or on the future, through anxiety. Anywhere but the present.”

Guilt has been compared to the brakes of a car. True, at times, it’s necessary to use the brakes — to stop, look back, and reassess. But if we spend our whole life on the brakes, we’ll never get anywhere. Most of our time needs to be spent pushing the gas petal, moving forward.

Moving Beyond

Shoshana Siegelman agrees. “The past is Hashgachah. “The future is bechirah. The dividing line is the present. Mothering is important, but it doesn’t determine how the children turn out. We’re responsible only for doing the best we can.”

People need to break the cycle of guilty negativism. Sometimes the best way out is to take a reality check from an objective observer. So much of our guilt is based on things beyond our control. An outsider can point out the truth: We may be much better than we think.

“What we’re trying to do is create a venahafoch hu, a complete turnabout in perspective,” Siegelman explains. If we can create a paradigm shift and reach a point of catharsis, even seeing the funny side and laughing over our distress, we can begin to work on it from an entirely different angle.

In her Kesher Counseling workshops, she teaches women to coaches one another. In this nonjudgmental setting, women can help each other change perspective. [See sidebar.]

“There is a tendency among us to want things to be okay. We think, I’ll deal with my problem for five minutes, and then I want to be able to say, ‘That’s done!’ But we need to acknowledge the complexity of the human psyche. We can feel pain even as we’re feeling joy. We can see problems clearly, while still being hopeful.”

Once we’ve committed ourselves to moving beyond our guilt, we can conduct an error analysis, arranging our lives to counteract difficulties. For example, a woman may feel guilty that she yells at her children. Letting go of the negative guilt, she can then analyze that this happens mostly at four each afternoon, as they come home from school. She may then realize that she needs a rest or a snack slightly before that time. By focusing on solutions, on correcting the problem, we’re growing beyond destructive guilt.

“In this way,” Siegelman points out, “we’re modeling the process of growth for our children.” Almost as an afterthought, she adds, with a smile, “And look at the benefit of guilt: It lets you appreciate your mother’s guilt about when she was raising you!”

Despite the jocular tone of this statement, perhaps we can indeed consider this idea of seeing guilt as a positive emotion. It allows us to see our own imperfections, so that we can work towards correcting them. And maybe seeing our own faults will help us to be more understanding and sympathetic to the flaws of others.

Keeping the Kesher

Everybody needs a listening ear and a compassionate shoulder to lean on. For some, professional therapists serve that role. Kesher Counseling workshops teach women to support each other, creating a network of support for women long before anyone reaches the crisis stage. Shoshana Siegelman refers to it as a “Caring Gemach.”

Each woman is paired up with a “listening partner” to whom she can express her feelings as she moves through the trials and triumphs of life. Then, midway through the conversation, the roles are switched; the talker becomes the listener.

The partners are taught to nurture each other, by listening well and acknowledging and reinforcing each other’s positive actions. They can also help each other set goals and identify resources for growth. The goal is not simply to give advice; rather, these women seek to empower each other to take action independently.

The beauty of Kesher Counseling’s program is that there’s no difference between giver and taker. Everybody has a struggle. Everybody has the capability to spread strength and encouragement. By sharing both the struggles and the strength, everybody benefits.

When Guilt Becomes Clinical

Sometimes, guilty feelings go beyond unpleasant; they can reach a point where they begin to take over. As Shalom Francis describes, many people have an “internal garbage can,” a corner of their mind where they mentally “stuff away” experiences that feel too painful to handle. Left to its own devices, eventually the “internal garbage can” may overflow, resulting in depression or anxiety attacks.

Although the growth resulting from working through our negative emotions is always laudable, certain symptoms render it particularly urgent. These include:

- Depression: can’t get out of bed, not functioning

- Anger: overreacting to minor disturbances, constantly tense and short-fused

- Feeling Overwhelmed: taking on too many responsibilities, including responsibility for the struggles of others and the perfecting of others

- Perfectionism: afraid to be wrong, afraid to take reasonable risks for fear of failure

- Obsessive Thoughts: recurring guilt thoughts, criticisms constantly replaying themselves in the mind

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 54)

Oops! We could not locate your form.