The Biggest Heart of All

| April 21, 2021Alter Mordechai Morel wasn’t supposed to live to his first birthday. But for the next 36 years, he defied the odds. Knowing any day could be his last, he made every minute count

Illustration: Menachem Weinreb

The young couple was in the process of redoing their bathroom, and as often happens with construction, things were not going quite as planned. “It’s so annoying,” the wife complained to her husband. “The vanity didn’t come out right, and the whole project is costing so much more than we expected.”

The husband was contemplative. “Is either of us sick?” he asked. “Is either of us in the hospital? Then we don’t get upset about this.”

For any other young couple, the husband’s words might have been a high-minded, but largely futile, attempt at diffusing his wife’s frustration through philosophical reasoning. But for this particular couple, Alter Mordechai and Rivky Morel, these words were no mere platitudes, since both had been seriously ill all their lives — he with a heart condition, she with cystic fibrosis.

Alter Mordechai knew, better than anyone else, that any day could be his last. And that, perhaps, is why he enjoyed every day of his life so much.

Five-Percent Chance

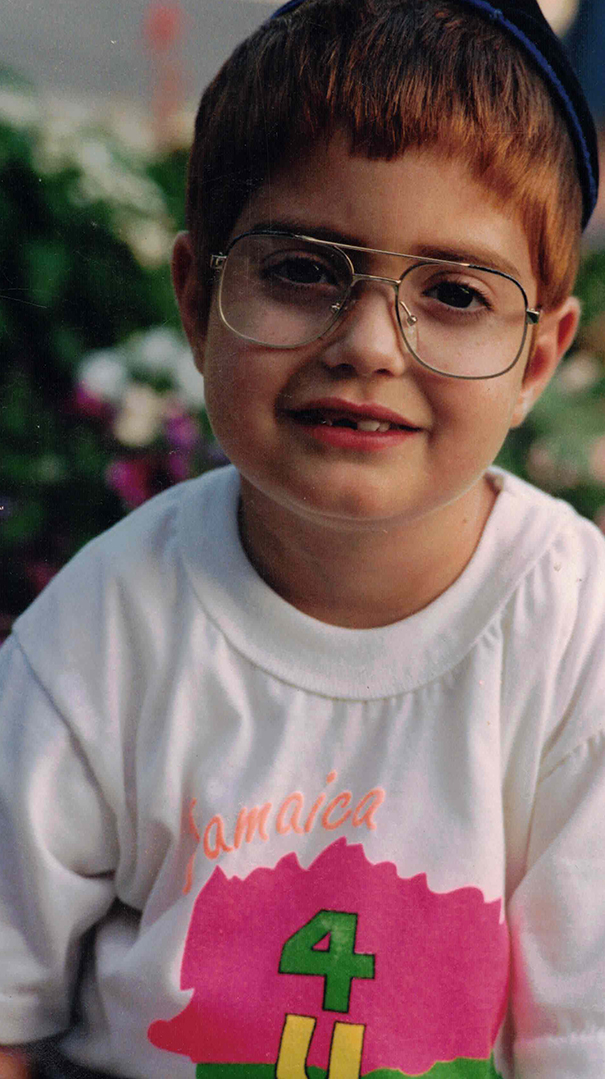

Back in 1985, when little Mordechai Morel was a baby, the doctors in Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children didn’t think he would ever make it to adulthood, much less finish Shas, get married, hold down a job, and enjoy a full, vibrant life. Diagnosed at the age of four months with multiple congenital heart defects — hypoplastic left heart syndrome, transposition of the great arteries, coarctation of the aorta, and subaortic stenosis — he was given a five-percent chance of surviving until his first birthday.

For his parents, Avrohom and Joyce Morel, this diagnosis marked the beginning of an epic 36-year battle to keep their son alive — and to ensure that his life would be one worth living. When he was about half a year old, he became septic, and his temperature dropped. His parents added the name “Alter,” after which his condition stabilized and his temperature returned to normal. The Morels also received a brachah from the Manchester Rosh Yeshivah, Rav Yehuda Zev Segal ztz”l, that they would merit to walk their son to the chuppah.

By the time he was two, feisty, redheaded Alter Mordechai had already undergone four major heart surgeries and required a pacemaker to keep his heart functioning, a feeding tube to ensure he received adequate nutrition, and multiple medications to treat his congestive heart failure. At the age of two, he suffered a stroke that affected the right side of his body, but as would happen countless times throughout his life, he quickly rebounded — this time, by becoming a lefty.

When Alter was three, his parents brought him to Toronto’s Yeshiva Yesodei HaTorah for his pre-cheder interview, and his mother informed Rabbi Asher Bornstein, the menahel, that Alter Mordechai took diuretics, wore diapers, and might never be toilet trained.

Rabbi Bornstein replied, “So what?”

That response set the tone for Alter Mordechai’s chinuch, in school as well as at home: He was a regular kid. This, even though he looked very obviously ill: His hands and feet were always blue due to poor blood oxygenation and circulation, and he was markedly smaller and weaker than his peers.

By the time Alter was ten, his heart was failing, and he urgently required a heart transplant. Despite his young age, he fully understood the ramifications of having his heart removed and replaced with another. When he was informed that a heart had been found for him, just before his 11th birthday, he asked, tentatively, “Was the other person niftar yet?” And when the doctors requested his consent for the procedure, he told them, “I’m too scared. You’ll need to get consent from my mother.”

During Alter’s transplant — and every other procedure Alter underwent at SickKids — hospital chaplain Gittie Edery was a steady, reassuring presence at his parents’ side. In fact, Alter referred to her as “Auntie Gittie” for the rest of his life.

Joyce, who’d always had an interest in medicine but had shelved her dream of becoming a doctor in favor of caring for her family, was constantly at Alter’s side throughout his every medical crisis. Even before she finally became a doctor at the age of 42, she often knew better than the hospital staff what Alter needed, and on many occasions she prevented them from giving him the wrong treatment, or overdosing him by giving him more medication than his undersized body could handle.

A Good Thing I’m Not Perfect

After Alter’s heart transplant, the antirejection drugs he was on caused his previously cherubic face to sprout abundant facial hair, even though he was barely 11. Once, when another kid spotted the short-statured Alter, whose face was covered with red hair, he loudly announced, “Baruch atah Hashem Elokeinu melech ha’olam — meshaneh habrios.”

“Amen!” Alter replied.

“People would often stop and stare as Alter passed them, and then turn around and watch him from behind,” Joyce recalls. “But he would tell me, ‘That’s their problem.’ ”

Alter confided to Ari Ullman, his childhood buddy who suffered from kidney disease and spent much time in the hospital with him (see sidebar), that it did bother him when people stared; he just chose not to let it get to him. He possessed unusual self-esteem that neither his appearance nor his physical limitations could dampen.

“Alter would joke that it was a good thing Hashem hadn’t created him perfect,” says Ari Ullman. “Because then, he said, the world wouldn’t have been able to handle his brilliance.”

While Alter did experience frustration and disappointment, he got over these feelings quickly. “He expected to grow taller after his heart transplant,” Avrohom Morel recalls, “but he didn’t, and the doctor told him he wouldn’t, even though he was only 11. When he heard that, he was very upset, but within a few days he was back to himself, ready to take on the world.”

“He never asked ‘why me,’ ” adds Joyce. “He accepted that this was the life Hashem had given him.”

Alter’s transplanted heart failed when he was 18, necessitating a second heart transplant. Still, determined to live a normal life, he followed his older brother, Yitzchak, to Eretz Yisrael, where he learned in Rav Tzvi Kaplan’s yeshivah and then in the Mir.

Each of Alter’s siblings — Hadassa, Esther, Yitzchak, and Baruch Meir — settled in Eretz Yisrael after they got married, and, in 2012, Avrohom and Joyce made aliyah as well. Alter remained with his family in Eretz Yisrael for several years, until he was diagnosed with post-transplant lymphoma, a form of cancer common in immunosuppressed transplant recipients, at which point he returned to Toronto for treatment.

In Toronto, Alter landed a job working at Cambridge Mercantile, a foreign currency trading company owned by Mr. Benzion Heitner, the father of his friend Yerachmiel. He was hosted by many families in Toronto, often spending months at a time at their homes. He was particularly close with Shmuel and Leah Yunger, old family friends who’d supported the Morels through many of Alter’s medical ordeals — Joyce called Leah “Alter’s mother on this side of the ocean.” Alter also developed a close connection with his cousins in Monsey, Avrohom and Leah Rovner and their children, who became his surrogate family.

Made in Heaven

As the years went by, Alter’s friends all got married — including Ari Ullman, who had undergone multiple kidney transplants. “My getting married gave Alter hope,” Ari explains. “If I got married, so could he.”

“Alter never doubted that he would get married,” his mother adds. “For him, it was a question of when, not if.”

Buoyed by the brachah of the Manchester rosh yeshivah, Avrohom and Joyce, too, were confident that Alter would find his zivug. But who would be willing to marry a survivor of two heart transplants and cancer who stood four-foot-seven-inches tall?

During his engagement, Alter met a friend of his mother’s, and confessed to her that he was stressed over his upcoming wedding. His and Rivky’s was no ordinary shidduch, and their respective medical conditions placed some unusual obstacles before their path to the chuppah.

“Well,” his mother’s friend responded, “you’re no stranger to stress.”

“No,” Alter replied. “I never have stress.”

And he meant that.

“Alter lived in the present,” explains Leah Yunger. “He didn’t worry about the future, and he always looked at the positive and found a way to enjoy life. He liked to say, ‘If life gives you lemons, drink beer.’ ”

When Alter underwent hip replacement surgery in 2016, due to medication-induced osteoporosis, the surgical team didn’t have the size hip he needed, and the one they inserted left him with a permanent limp. “I was so upset when he told me about this,” Leah recalls, “but he laughed it off. To him, it was a nonissue — it wasn’t going to limit him from living his life, so it was good.”

Before Alter’s wedding, Ari Ullman offered him some brotherly advice. Knowing that Alter had spent much of his life at the receiving end of people’s favors and consequently had no trouble asking people to help him out — “He didn’t mind calling the whole world to get a ride a block and a half” — Ari was concerned that his kallah would feel imposed upon by his needs. “If you pull this shtick with her, telling her to butter your bagel and do this and that for you,” he warned Alter, “she’s not going to stand for it.”

Alter had no plans of imposing on Rivky, though. He wanted her to feel that he was her protector and hero, not to feel that she had married a sick, needy person.

“He always liked to do things for me,” Rivky says. “For him, every day was a reason to celebrate.”

When Alter would offer to take Rivky out to eat on a random day, Rivky would ask him, “But why?”

“Because we’re alive!” he would declare.

“He felt he had to do whatever he could today,” Rivky explains, “because we didn’t know what would be tomorrow.”

When a cousin from Los Angeles celebrated his bar mitzvah, Alter wanted to attend, even though he had needed a cane to get around, due to his wrong-sized hip. Another cousin, Goldy Fein, thought it was absurd that Alter was even entertaining the idea of traveling to the bar mitzvah, considering his medical condition. But Alter told her, “If I have an opportunity to be at a simchah, why wouldn’t I? And if I have the opportunity to go see the world, why wouldn’t I?”

“Not only did Alter and Rivky go to the bar mitzvah,” Goldy adds, “they trekked all across California — and sampled any kosher food there was to be had along the way.”

Never Afraid

Alter and Rivky would accompany each other to their respective medical appointments, but they had very different attitudes toward their health. “I would worry about things like pending results of a medical test,” Rivky admits. “But Alter was never afraid. He would say, ‘Everything is for the best. This is another test that we’re going to pass, and it’s going to be okay.’ His emunah was incredible.”

Many people come home from work some days — or every day — frustrated. Not Alter. “He felt so lucky that he was able to go to work,” Rivky says. “He didn’t take anything for granted. He was so grateful to have a job, and so happy that he could be a regular person, that he never complained about his work.”

Alter’s enthusiasm and devotion made him a valued employee, despite his frequent absences due to his medical condition. When he married Rivky and moved from Toronto to New York, Mr. Heitner transferred him to the Manhattan branch of Cambridge Mercantile, where he worked in the trading department.

When that branch of Cambridge was sold to a different company, Alter continued to work at the same job. “I always suspected that Mr. Heitner put a clause into the contract requiring the new owners to keep Alter on,” says Joyce. “After Alter’s petirah, I asked Mr. Heitner straight-out if that was the case, and he confirmed that he had requested that Alter be able to stay on after the sale.”

Alter’s engaging nature, upbeat attitude, and cheeky wit endeared him not just to his boss, but to practically everyone who met him. Each time he was admitted to Toronto General Hospital, the nurses would assign him a private room, even though that was a perk that usually had to be paid for. And philanthropists in the Toronto community vied for the privilege of offering him financial support. One of them even gave him a credit card with no spending limit — although he quickly switched that to a fixed allowance after receiving Alter’s first bill.

“I worried about money,” says Rivky, “but Alter never did.” To him, life was an adventure waiting to be experienced, and neither financial constraints nor his own physical limitations could stop him from living life to its fullest. “You would think that someone with a body like that would be held back from doing what other people do,” Rivky observes, “but he always did more than anyone expected him to do. He’s living proof that you don’t need a guf — you just need a neshamah.”

Two Hearts, Two Lungs, One Soul

To Alter, getting married was the ultimate proof that he was a regular person, and he would wave that proof proudly whenever he could. “He would always introduce me as ‘my wife,’” says Rivky. “Saying those words gave him so much joy.”

The first Purim after Alter and Rivky got married, the ever-creative Rivky put together costumes for them based on The Wizard of Oz: She dressed up as Dorothy, while he dressed up as the Tin Man, who, in the original story, pined for a heart. On his silver costume, Alter wore a sign that read, “She stole my heart.”

Rivky describes theirs as a “fairytale marriage,” and indeed, anyone who saw them together recognized immediately that this was a relationship to be envied. Knowing that their marriage was nothing short of a miracle and that their fairytale could end abruptly at any point, they keenly appreciated each day they had together.

Alter’s secret to shalom bayis? “He didn’t sweat the small stuff,” says Rivky. “He knew that life is short, so he tried to make every day memorable and enjoy it to its fullest.”

Alter and Rivky’s motto was, “Two hearts, two lungs, one soul,” a reference to his two heart transplants and her double lung transplant.

Having both defied tremendous odds to get to where they were, they returned as a couple to the respective hospitals where they had each been treated, proudly introducing each other to the doctors and nurses who had cared for them since childhood. The doctors and nurses kvelled.

“When you’re a transplant recipient,” says Rivky, “you’re living on borrowed time. It’s not like the doctors send you out of the hospital after your transplant and say, ‘Oh, have a good life.’ What they tell you is, ‘Maybe you’ll have another five years.’ ”

Accustomed as she was to embracing life and overlooking the minor annoyances that tend to cloud people’s joie de vivre, Rivky nevertheless experienced frustration when their bathroom renovation didn’t go as planned. But Alter’s words to her at that time — “Is either of us sick? Is either of us in the hospital? Then we don’t get upset about this” — took on frightening new meaning the very next day, February 4, 2019, when he collapsed at his Manhattan office and had to be rushed to nearby Columbia Presbyterian Hospital.

His heart was failing again, so the staff at Columbia attached him first to an external pacemaker that administered painful electric shocks, and then performed emergency surgery to insert an internal pacemaker. Joyce flew in immediately from Eretz Yisrael to be with him, and she would remain with him for most of the next two years until his petirah.

Something went very wrong during Alter’s pacemaker surgery. He began to hemorrhage and soon went into shock, after which his kidneys failed. From then until the end of his life, he required dialysis regularly.

Alter was released from the hospital just before Pesach of last year, but he was very weak, and the wound from his pacemaker surgery soon opened because it was infected. By the summer, he was back in Columbia, having gone into shock due to heart failure caused by dialysis issues.

The wound still had not healed fully, but the staff at Columbia were loath to perform another surgery. Phrases like “quality of life” were frequently bandied about by the medical team, many of whom believed that Alter should be allowed to die “comfortably.”

Alter would not hear of it, however. He wanted to live, regardless of his quality of life, and regardless of how much pain he was in.

Worse Than a Heart Transplant

In February 2020, just before COVID-19 hit, Joyce flew with Alter from New York to Eretz Yisrael, where she continued to serve as his full-time caregiver, both at home and in Shaare Zedek, where he was hospitalized with sepsis just as Israel was entering its first lockdown. Tests run in Shaare Zedek revealed that he was suffering from endocarditis, an inflammation of the inner layer of the heart. His infected pacemaker needed to be removed, but his condition was so complex that he needed a world-class team to perform that operation.

With the help of medical askanim, in October 2020 Alter was accepted to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. But he was in no state to travel from Eretz Yisrael on a regular flight, especially with the hovering threat of COVID, and with Israel locked down and most flights canceled. His friend Yerachmiel Heitner decided to call Eli Rowe of Hatzolah Air, whom he had met when Eli was in Toronto raising money for that endeavor. Eli told Yerachmiel that he had just landed in Tel Aviv with two niftarim, and was heading back to the US that night with a child who needed surgery abroad. He didn’t hesitate to take Alter and his mother on that flight.

“These things just seemed to happen around Alter,” notes Yerachmiel. “Miracles like these were the norm for him and his family.”

At the Mayo Clinic, Alter’s pacemaker and the surrounding infected tissue, including part of his sternum, were removed. The surgery was successful, and by the next day Alter was up and about, after months of having trouble moving around independently. After a couple of days, however, he contracted pneumonia.

“From then on, it was one infection after another,” recalls his sister, Esther Emanuel. She and her siblings took turns visiting Alter and their mother, who had taken a leave of absence from her medical practice in Jerusalem to be with Alter in Rochester — far from any family, and a one-and-a-half-hour drive from the nearest frum community in Minneapolis.

Despite Alter’s dire condition, last summer he told a cousin of his that he was going to be okay. “How do you know?” his cousin asked.

“From experience,” he said dryly.

Considering Alter’s medical challenges, he could easily have despaired. “His list of conditions was so long,” says Joyce, “that no doctor ever managed to read through his entire chart. They’d walk into his room expecting to see a hunched-over nebach, but then they’d find this cool dude in the bed, cracking jokes.”

Alter would make light of his medical procedures. When informed that he needed a colonoscopy, he said, “Oh, that’s worse than a heart transplant.”

“If you have expectations, then you’ll be disappointed,” Alter once told someone. “But if you have no expectations, then everything is a gift.”

I Need a Huge Miracle

“Toward the end,” says Joyce, “Alter realized that he was going to die, but still, he wanted to receive any treatment that could save his life. He wanted his antibiotics changed, he wanted to be intubated, he even wanted to undergo surgery that he knew might kill him — all because he wanted to keep on living. He never gave up.”

Alter kept on fighting until the very end, even as he and the people close to him realized that the end was near. “I don’t just need a miracle,” he confided to his friend Ari Ullman. “I need a huge miracle.”

Still, Alter didn’t ask “why me.”

“He had only one complaint,” says his wife. “‘Why does Rivky have to suffer because of me?’ “

Not wanting to be a burden on Rivky, Alter refused to videocall with her from the hospital, because he did not want her to see him looking ill. Until he was too weak to talk, he spoke to her on the phone several times a day, while trying to protect her from knowing the grim details of his condition.

When people would visit Alter in the hospital, he would often say, “You think I’m suffering? Imagine what Rivky’s going through! She’s suffering double — for herself, and for me.”

Before he got married, Alter made a siyum on all of Shas, and for years afterward, he continued to learned daf yomi over the phone with his brother Baruch Meir and his brother-in-law Eli Emanuel, who were both in Eretz Yisrael. Once, he told Ari Ullman that these daily learning sessions were often too difficult for him. “I appreciate that my brother and brother-in-law don’t miss a day, but sometimes I’m just not up to it,” he admitted.

“So just tell them you don’t have koach,” Ari suggested.

“I can’t,” said Alter. “My days may be numbered, and what am I going to say in Shamayim?”

“Oh, you don’t have to worry about that,” Ari assured him. “You have a free pass to Gan Eden.”

“Yeah?” Alter wondered. “You think it’s going to work?”

He kept up that learning seder, just in case.

Hello, Not Goodbye

During the last few months of his life, Alter was taken to the Mayo Clinic’s intensive care unit numerous times when his blood pressure plummeted. On March 4 of this year, his blood pressure was a shockingly low 45 over 35, yet he insisted he did not want to go to ICU.

“Alter,” his mother said, “if you don’t go to ICU, you’re going to die now.”

“Of course I want to go to ICU,” he responded. Much as he loathed being in intensive care, if his survival depended on it, he was going.

“That means you’re going to have to be intubated,” Joyce continued. “Is that what you want?”

“Yes,” Alter said firmly.

“He was willing to do anything just to keep on living,” Joyce explains.

Before he was intubated, Alter called his wife and each of his siblings — “to say hello, not goodbye,” Joyce emphasizes.

Although they all sensed this was goodbye, they didn’t really think it was the end. “Alter was — Alter,” his sister Esther reflects. “He survived so many other things. We didn’t believe it was going to happen.”

On Sunday, March 14, Avrohom Morel flew from Eretz Yisrael to Minnesota to say goodbye to his son. On Monday, Alter was still able to communicate with him, despite being unable to speak due to his breathing tube. The next day, Tuesday, March 16 (3 Nissan), he passed away.

At the levayah in New York’s JFK Airport, before Alter was taken to Eretz Yisrael and interred in the Eretz Hachaim cemetery in Beit Shemesh, his cousin Motty Stefansky said, “Alter taught me how to live life and enjoy every second. I never ever once heard him complain. I called him two weeks ago and I said, ‘Alter, please, just complain once so I don’t feel like an idiot.’ He said, ‘I’ve been sick for 36 years — what am I going to complain about now? You can complain, but I don’t need to complain.’ ”

In every picture, Motty noted, Alter is seen smiling and cheerful. “He wanted us to be b’simchah,” he reflected. “That’s how he would want us to carry on.

“He had the smallest heart, the worst heart,” Motty concluded. “But he had the biggest heart of all.”

Memories of Alter Mordechai can be sent to the family at: memoriesofalter@gmail.com

Yaffi Ullman

You might remember him as Alter Mordechai ben Fraida, his name forever etched on the classroom blackboard. Others would be added or erased, but his Tehillim name was a steady presence on our list of the sick to pray for.

As far back as I can recall, Alter and my brother Ari were the redheaded duo. They’d race around SickKids giving the nurses at the clinic a run for their money. He was my brother’s first real friend and the only play date my mother could realistically consent to. I recall how in the era before cell phones, his mother once checked my brother’s blood pressure, and concerned, drove him straight to the doctor as if that was the most natural place for a play date to end. The boys came home with goofy grins as they recounted an afternoon of projectile vomiting and blood work like it was all fun and games, and I suppose with a friend by your side, it might have been.

They grew up together, and in a strange world of constant pokes, procedures, and surgeries, a best friend made it so normal. They shared a bond over experiences no other first grader could relate to, and in their own way, they made sure to find time for pranks and mischief even when there was bullying or disappointment at never making the baseball team. At one point, as a teen, Alter was hospitalized and bored to tears, so my brother and another friend offered to run down the block and find something to entertain him. Alter promptly unplugged his IV pump and insisted on joining, and the trio snuck down University Avenue, hospital runaway in tow.

As my brother grew older, his medical condition stabilized, and hospitals and transplant clinics were no longer center stage. Alter was less fortunate, and it seemed as though that boy could never catch a break. His heart transplant side effects included major hurdles like cancer, diabetes, organ failure, and a long list of other issues. Still, the two friends managed to rejoice at each other’s weddings. They flew in to be there for big surgeries and we’d laugh each time, calling Alter a cat with nine lives, and he let us poke fun in his lighthearted way. In a lifetime of pain and hurdles, Alter was blessed to know true love, and his wife brought so much happiness into his last years.

It seemed as though he’d live forever, and we were so sure he’d greet Mashiach in his lifetime. No matter what got thrown in his way, he’d come out the other side, ready for an adventure — or at the very least a beer and a good video game competition. Capitalizing on Alter’s generous nature, my brother would mooch off tickets to sports games, free dinners, and all the fun stuff you got when Alter was at your side. The unfiltered questions my younger siblings peppered him with never fazed him, and when they demanded to know why he was so short, he didn’t miss a beat in his response, telling them that it was because of all those missed breakfasts. Suffice to say, no one made a fuss over breakfast around here since!

Alter was part of our lives from the very beginning, and it feels like he’s always been part of my family. And while I’ll never understand the pain and suffering he endured, I think about the power of friendship, the importance of having someone in your corner who gets what you’re going through, and more than anything else, the strength of a mother. Alter’s mother kept him alive by sheer will, it seemed, and if ever a mother’s love could be measured by strength, hers would shatter boulders. The veteran staff at SickKids speak of her with reverence, and once she got her son over his major medical hurdles, she went on to start medical school, and she continues to fight the good fight for her patients.

Alter passed away with both his parents by his side, and I hope they find solace in the joyful moments he experienced, the kindness extended to him, and his unbreakable spirit.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 857)

Oops! We could not locate your form.