The Big Red Retail Revolution

| July 11, 2023To attract foreign currency into the state coffers, the government opened a chain of stores named Torgsin (a Russian acronym for “Trade with Foreigners”)

Title: The Big Red Retail Revolution

Location: Soviet Russia

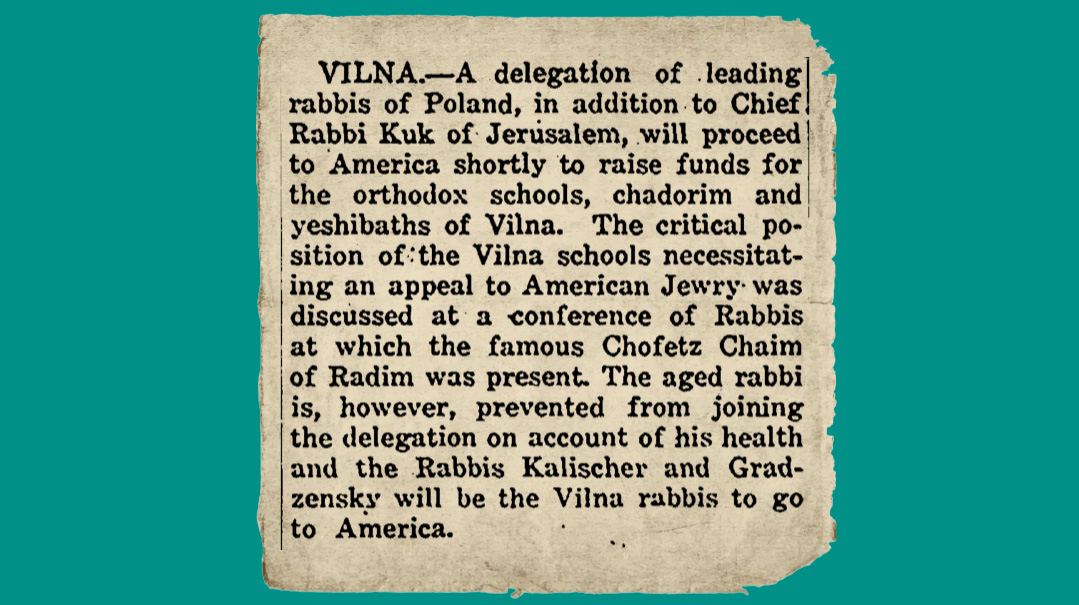

Document: Torgsin ads from Jewish newspapers

Time: 1930–1936

Recent reports from the Soviet Union show that the stores operated by Torgsin (the State Corporation for Trade with Foreigners) did record business last year and are steadily improving the quality and variety of their merchandise. Thousands of Americans of Russian extraction are using the Torgsin stores to send gifts to relatives or dependents in the Soviet Union. Special stores are maintained by Torgsin for customers who wish to have their furs, clothing, shoes, etc., made to order.

Torgsin will arrange for a vacation (including transportation) in any designated summer resort. It procures tickets for motion picture houses, theatre or opera. It sells all sorts of fruits in and out of season. It sells livestock, such as cows, horses, fowl, etc. The constant improvement of Torgsin services is a refutation of the stories occasionally spread in the United States that Torgsin is curtailing its activities or that recipients of Torgsin orders from foreign countries become objects of suspicion in their communities.

—Jewish Press (Omaha, Nebraska)

“The Great Turn” was a radical change in Soviet economic policy during the late 1920s under Josef Stalin. For a time in its infancy, the Soviet regime allowed limited private enterprise. However, that was abandoned in 1928 in favor of the first Five Year Plan, with the goal of rapid industrialization and agricultural collectivization under a very rigid “planned economy.” The Soviet Union was in need of foreign currency and precious metals in order to finance its investment in heavy industry, and the ruble couldn’t be exchanged as a currency on the international market. In order to attract foreign currency into the state coffers, the government opened a chain of stores named Torgsin (a Russian acronym for “Trade with Foreigners”).

These stores provided the Soviet population as well as diplomats and tourists an opportunity to buy goods that were scarce or not available in ordinary shops, using foreign currency, gold, silver, or other valuable possessions.

The Torgsin network stretched across the vast expanse of the Soviet Union, from Smolensk in the west to Vladivostok in the east, and from Ashgabat in the south to Arkhangelsk in the north. In return, the system funneled coins, precious metals, diamonds, and foreign currency back to Moscow. The starving Soviet population flocked to the nearly 1,400 Torgsin stores, but most quickly ran out of items of value to barter.

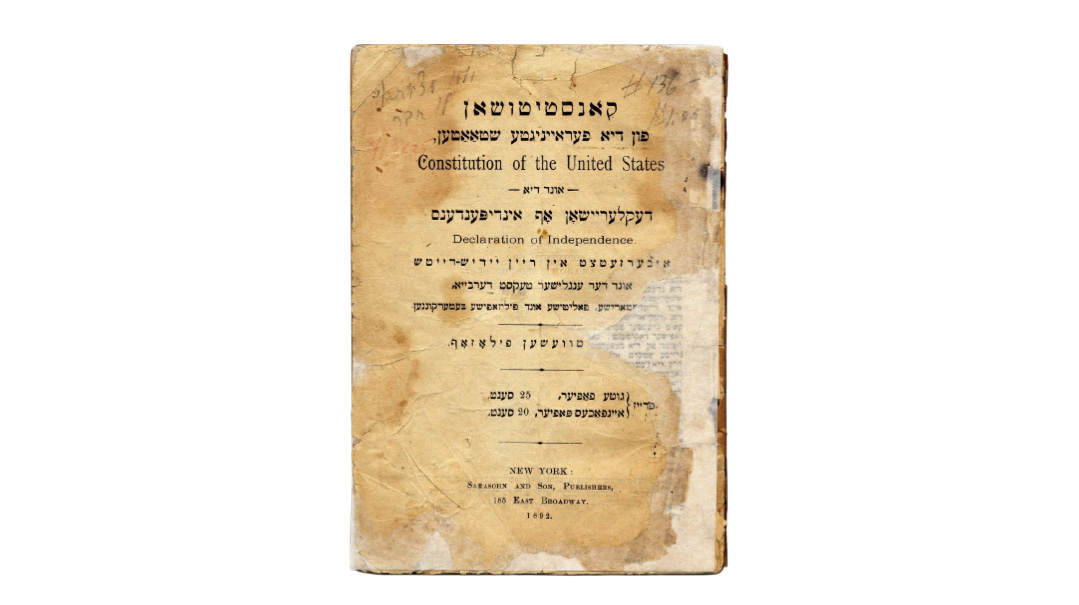

In 1931 Torgsin’s leaders embarked upon an aggressive marketing campaign targeting Jewish publications across the world. Articles were written and ads were placed in dozens of Jewish newspapers across America and Europe, especially prior to the holiday season, with the claim that “Torgsin is the easiest way to send food and gifts to your friends and relatives in Russia.” In order to facilitate the payment process, a deal was brokered with American Express to allow Americans walk into their local branch and fill out an order on site.

Torgsin stores emerged as a lifeline for Jews who were severely affected by the widespread famine across Ukraine during the Holodomor. The beleaguered populace realized that Torgsin, like many Soviet enterprises, was rife with corruption. Jewish families who received aid from relatives abroad via Torgsin vouchers also encountered unintended repercussions. Rural neighbors who became aware of this aid grew envious. This further fueled anti-Semitism, leading to increased animosity. The Soviet government took note as well, using these international connections to keep tabs on those citizens.

British prime minister Margaret Thatcher aptly remarked, "The trouble with socialism is that eventually, you run out of other people's money." While Torgsin added some $190 million (in today's value) to state coffers, by 1936 it had swindled Soviet citizens of their valuables and exposed the hypocrisy of Bolshevik leaders. Remembered for corruption, cronyism, and perhaps its gravest sin, capitalism, Torgsin became a symbol of everything wrong with "Stalin's paradise."

Rich Man’s Bread

By 1934, only one matzah bakery in Moscow remained legally open, operating in a local cemetery under the Great Synagogue's supervision. The condition was that flour had to be bought at local Torgsin branches. The Soviet regime, nearly having wiped out Jewish life in the country, initiated an ad campaign across the Jewish diaspora, promoting matzah purchases for their Russian brethren. This prompted one commentator to jest that Soviet Jewry should be grateful to the government for the reminder that Pesach was approaching.

Deceiving the Dead

A Jewish native of Borisov named Moisei Shkliar was Torgsin’s first chairman. A 1931 issue of Time reported that when Charles Recht, a lawyer representing New York Life Insurance Company, arrived in the Soviet Union to settle $3 million owed to 21,000 prewar policyholders, Shkliar refused to allow him to pay dollars to Soviet citizens, as it would constitute illegal “hoarding” of foreign currency. Shkliar proposed that the funds be deposited in Torgsin stores, which would distribute equivalent “purchase orders” to policyholders (with a deduction of a 25% “processing fee”).

For more insights on this story, we recommend reading Stalin’s Quest for Gold by Elena Osokina (Cornell University Press, 2021).

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 969)

Oops! We could not locate your form.