The Battle for Life Itself

| February 10, 2021Once Yankel Cohen started to learn, he became a bochur obsessed, falling under the Torah’s magic spell. Yet Reb Yankel didn’t travel alone on this lifelong adventure — he took us all along for the ride

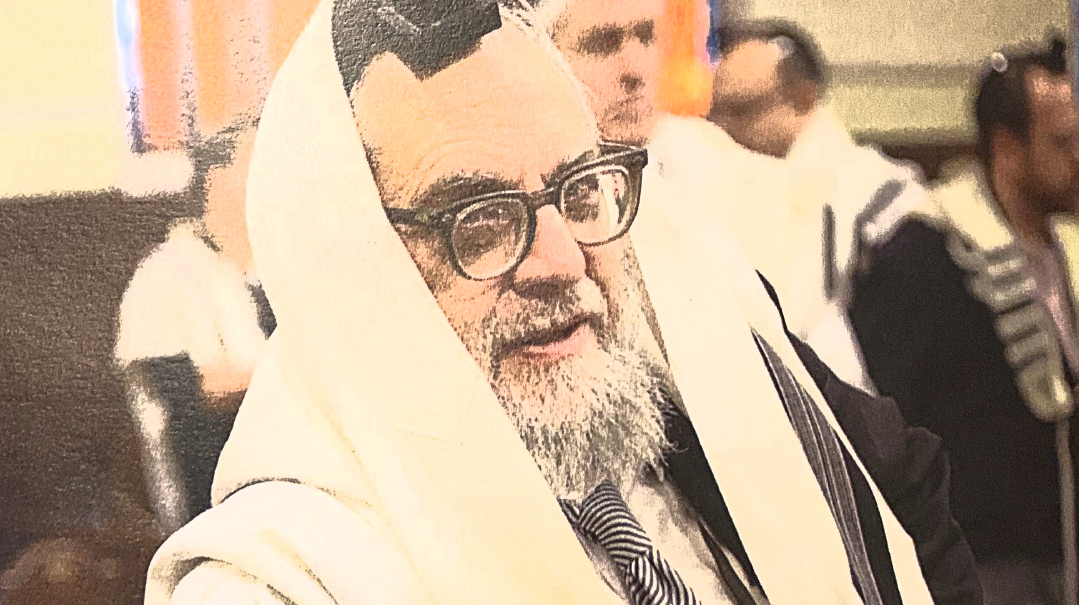

Photos: Naftolli Goldgrab, Family archives

When he first came to Telshe yeshivah in 1951, he’d sneak out to the baseball stadium, but once Yankel Cohen started to learn, he became a bochur obsessed, falling under the Torah’s magic spell. Yet Reb Yankel didn’t travel alone on this lifelong adventure – he took us all along for the ride, and for the next 70 years, let us know that the treasure belonged to all of us

“Dovid Hamelech, alav hashalom, said, ‘Lulei Sorascha sha’ashuai az avaditi b’anyi.’ And I too, announce in a loud voice, the words of hakaras hatov filling my heart toward Hakadosh Baruch Hu that He gave us His holy Torah, in which I found what my neshamah has loved, from my youth until this day.”

(From the introduction to the sefer Sha’ashuei Yaakov, by Rav Yisroel Yaakov Cohen, 2020.)

Devorim! Nifloim! Ad! Meod!

Bursting forth from random corners of the beis medrash, the words emerged from the man in the graying beard and the short-sleeved shirt, his vintage glasses perched upright on his nose. In those corners he built towering edifices, tore them down, and rebuilt them again. And we watched from the sidelines as he waged wars, climbed mountains, and swam the deepest seas. For 70 years, Rav Yankel Cohen ztz”l was the ultimate adventurer, engaged in the definitive adventure.

Torah Hakedoshah. And every beautiful secret it offers to those who plumb its depths.

If only my pen could reproduce that singular voice packed with 100 tons of gravel and the purity, love, and joy of the music it created. The soundtrack of my youth. Four simple words, repeated thousands of times by the man who loved the devar Hashem as life itself — who understood that it is life itself.

“I wish to express hakaras hatov… to my father and mother who sent me to the holy yeshivah in Telz, and to my rebbi, Rav Yaakov Nayman ztz”l, who guided and encouraged my parents in sending me…”

His story was an unlikely one. Born in late 1930s Chicago to an American-born father, Reb Yankel’s path to greatness was not a bet anyone was taking. Brilliant, popular, handsome, he was an all-American story waiting to happen.

Yisroel Yaakov Cohen was known as Jerry back then, and the star of every court and field he could find. The non-Jewish kids in the neighborhood would wait anxiously for his return from school. Without him, the games weren’t worth contesting. When he wasn’t playing, he was watching the Cubs in the bleachers at Wrigley, hanging onto every pitch and every big game.

And then, in 1951, his father decided 13-year-old Yankel was going to yeshivah. Not just any yeshivah, but to Telshe. The Telshe of Rav Elya Meir Bloch and Rav Mottel Katz. The citadel that, in time, would rewrite Torah history in the American Midwest and spread its light across the globe.

But Jerry was having none of it. There was no way he was going to a high school that didn’t even have a baseball team. All summer they argued, and when the family rav, Rav Yaakov Nayman, a talmid of the Brisker Rav, entered the discussion, Jerry finally relented, begrudgingly giving them two weeks with a promise that his dad would come get him if it wasn’t his place.

It wasn’t. Not yet.

Louis Cohen, the traveling salesman who wanted nothing more than his son to become a ben Torah, came to collect him, as promised. As Jerry packed his bags, he looked up and saw his father sobbing by the doorway. His soft heart melted. He would stick it out.

But he didn’t change overnight. Jerry still loved baseball.

He used to sneak down the famous Telshe hill to Euclid Avenue and catch a bus to Cleveland Municipal Stadium, or as we knew it as kids, the “Mistake by the Lake.” One day his absence was noticed and members of the hanhalah came to the rosh yeshivah to discuss their response. The answer came swiftly:

“Mach a shveig — Just keep it quiet.”

Jerry Cohen, for his part, was gutsy. One day he noticed an older bochur smoking. He reached out, broke the cigarette, and took off running for his life. Not exactly looking where he was going, he banged straight into an oak, fell, and began to bleed. Another choshuve bochur saw what had unfolded, rushed over, and patched him up. From that moment on, he took Yankel under his wing and prodded him forward.

You see, in the America of the 1950s, something big was happening in downtown Cleveland. It was the time of Rav Avraham Mordechai Isbee, Rav Zelig Nevis (of whom Rav Yankel would write “the man from whom I learned a bit of what hasmadah is”), Rav Sholom Shapiro, and the other lions that Rav Elya Meir and Rav Mottel developed and unleashed on the Torah world.

And Rav Yankel Cohen took his place among them.

Yankel started to learn, became obsessed, and fell completely under the spell of the blessing of ameilus b’Torah.

Eventually, the time came for the Telsher masmid to find a partner in life. Someone who understood kavod haTorah and would share in the promise of a genuine gadol b’Torah in the making.

Ruthie Fishbein was a student of the iconic Williamsburg Bais Yaakov, a talmidah of Rebbetzin Vichna Kaplan and Rebbetzin Basya Bender. She grew up in Eretz Yisrael and hailed from a family who revered Torah and talmidei chachamim. Her father, Reb Chaim Dovid, had learned under Rav Yosef Tzvi Dushinsky, whom he considered his rebbe. When Ruth was a little girl, her father had taken her in for a brachah as well, although it wasn’t customary to bring in girls to Rav Dushinsky and it startled the onlookers.

“Zolst du zichen a gitten bochur, you should look for a good bochur,” the Rav told her then.

She found him, and the last piece of the puzzle had fallen into place.

A Cleveland personality in her own right and an attorney of considerable prowess, she laughs over the phone, remembering getting through law school. Yankel, a math whiz, helped her with her statistics class and pitched in where he could. He made a mean cholent, and many of us saw him mowing the lawn.

That was the thing about Yankel. He was so connected to his learning, that he was able to do everything else — sometimes it meant that the beis medrash just moved to the kitchen.

She tells me of the time they both stood at the counter preparing for Shabbos, when a rebbi in the yeshivah called, struggling with his shiur. At the countertop and with no seforim in sight, the difficulties fell away and clarity emerged, as if rising from a pile of potatoes. There too, Torah was created.

Sulam mutzav artza v’rosho magia hashamayma. He was aware of everything going around him and never shirked an ounce of responsibility. And not for an instant did he leave the shtender standing upright in his mind.

“I have no words to thank my dear wife, Rus, who throughout all the years sacrificed greatly and took upon herself the burden of parnassah, so that I could toil in Torah with no disturbance. What belongs to me, and to my students, and to all those that are destined to learn from this sefer, belongs to her.”

The hours he kept were both a testament to his immense physical endurance and the burning desire to grow and to know. Rav Getzel Fried, one of Wickliffe’s great talmidei chachamim, remembers being told upon entering the yeshivah about an older bochur who learns 20 hours a day.

In yeshivos everywhere, Friday is the day for errands, some shopping, and maybe a game of baseball. Reb Yankel took a break on Erev Shabbos too — for 15 minutes, to change into his Shabbos attire. As a boy, Rav Avraham Ausband, the Riverdale rosh yeshivah, was his chavrusa for Pesach bein hazemanim by virtue of his living on campus. Because for Reb Yankel, winter zeman ended Erev Pesach. After he moved to Cleveland Heights, summers would find him stationed in a neighborhood shul, upstairs in the ezras nashim, all day, with no air conditioning and no one watching.

He would eventually join the hanhalah of the yeshivah that had raised him to greatness. He was appointed as mashgiach and began to say shiurim for a select group. You didn’t need to be the biggest lamdan or the best guy in the class, you just had to repeat the shiur back to him — it signaled commitment. Wanting to learn was all that he required. He would do everything in his power to give you the rest.

When he was a bochur, there was a curfew in yeshivah. At some point, the lights were shut and the bochurim were urged to get to bed. The Munkacser Rebbe, who was also a student there, told of the night Reb Yankel found a flashlight and continued their seder in the darkened beis medrash. The light peeked through the windows and Rav Mottel came to break up the covert session. As the Rosh Yeshivah approached, he saw who it was.

“Ah, it’s Yankel. Yankel is different.”

Yankel was different. Not just in the sheer amount of time he spent in the pursuit of his obsession, but in the energy and life that pulsated through his entire being.

At his kabbalas panim he got up to say the chassan Torah. He became so enwrapped that it seemed as if he had forgotten where he was, until Rav Gifter stepped in. “Genug, Yankel, mir darf gein tzu der chuppah — Enough, Yankel, it is time to get going to the chuppah.”

He continued the shtikel by sheva brachos, and when he finally brought it to its satisfying conclusion, Rav Gifter exclaimed, “A leibedige sefer Torah!”

It was the perfect description. Because Yankel Cohen embodied Torah as a breathing reality. In fact, he called Rav Elchonon Wasserman his rebbi, even though they had never met. Yet he sat in his shiur every single day, because for Reb Yankel, Kovetz Shiurim wasn’t just a sefer, it was his ticket to finding a seat on the benches of Baranovich. Rav Elchonon was alive, as was every word of Torah he ever spoke.

Each new gain in clarity, no matter how small it seemed to be, evoked such emotion, such raw passion. When there was a new chiddush, the yeshivah turned over. A battle for life itself was underway and until the truth took shape, no one had the right to sit it out.

“I must thank, with unlimited praise, my faithful talmid Rav Dovid Feigenbaum shlita, who turned nights into days with faith and love, in order that the words should be published with precision and care, so that not even the smallest insight should be changed or lost.”

“Ein l’Hakadosh Baruch Hu b’olamo ela daled amos shel halachah bilvad — Hashem only has the four ells of halachah in This World.” And yet, we know Hashem’s glory fills every corner of the world. There is no nook or cranny empty of His light. And so it was within the four amos of halachah where Reb Yankel dwelled uninterrupted his entire life. He never ventured out, but he made room for each of us inside.

Everyone felt his authenticity, how much he wanted you to taste the thrill of his lifelong adventure. The entire corpus of Jewish thought was at his fingertips, but it wasn’t just his to hoard. We all had a part in it, and he mastered the art of sharing that feeling. It doesn’t belong to me, he would let us know, it belongs to us, with a capital U.

There was a boy who had learned in yeshivah, but who had abandoned Yiddishkeit and was angry at anyone representing the world he had left behind. During Reb Yankel’s final illness, the fellow reached out. He wanted to visit. The talmid fielding the call made it clear that coming to see him meant sitting and learning. Schmoozing wasn’t part of the deal.

“With Reb Yankel, I’m willing to learn for an hour,” said the caller. “He is real, and his Torah is so geshmak.”

Reb Yankel made Torah accessible. His clarity and knack for distilling complicated Talmudic concepts into practical terms that even the most uninitiated could relate to was famous. A new tzad on shlichus was likened to a washing machine, and the difference between a goseis and a treifa was the difference between a new tire with a hole in it and a tire that was bald. He wasn’t shy about asking scientists about questions on cloning, doctors about refuah on Shabbos, and landscapers for help with Zeraim. Each man he met was his next chavrusa, even if the unsuspecting fellow didn’t yet know it.

Like his father before him, Reb Yankel was a traveling salesman. His overflowing cart of chiddushim came with him wherever he went — in the beis medrash, on buses, cars, and planes. And every tool at his disposal was used — including his legendary sense of humor.

Selling Torah, always selling. Friends he hadn’t seen in years, random strangers, sons, son-in-law (his phone chavrusa for over 30 years) and grandchildren. The shalom aleichem was the same for everyone.

A bochur from Telshe was traveling to Eretz Yisrael, and when Reb Yankel spotted him in the terminal, he was ecstatic. “Baruch Hashem, I have a chavrusa!”

The boy wasn’t sure how he was going to learn for 12 hours straight. But there was nothing really to worry about; their seats were in different sections of the aircraft. Until Reb Yankel made his way to the flight desk, that is.

“This young man must be seated next to me,” he told the flight clerk.

One of his signature binders was pulled from his carry-on and away they went. Four hours in, the boy began to get restless and remembered the sleeping pill his father had given him. Reb Yankel had mentioned his difficulty sleeping on a plane. The bochur finally had an out. Before he could pass on the warning of its potency and that his father had told him to split it in half, the pill was swallowed whole. There was no way he would hear from his seatmate until the wheels were safely on the ground.

An hour later, Reb Yankel stirred.

“Okay, I needed that. Vaiter! Let’s continue!”

Reb Yankel’s passion wasn’t just reserved for his own original thoughts. My third grade rebbi, Rav Dovid Meyers, taught the parshiyos of Terumah and Tetzaveh and became a world-renowned expert on the topics of Mishkan and bigdei kehunah. For years, he worked on his seforim and Reb Yankel had a hand in every word. Every day after Minchah, for over 30 years, they had an appointment to discuss his progress. On a trip to Eretz Yisrael, Reb Yankel was given over 400 pages of the evolving manuscript. It came back with comments lining the margins.

He handed it over and flashed his signature smile. “Reb Dovid, I’m behind a week in the daf and it’s your fault.”

“And in these days when I am in and out of hospitals, I see tangibly how beautiful is my portion, that Hashem has given me the privilege of delighting in words of Torah. In truth, I had not known the extent of the greatness of the chesed He has shown me until I saw other ill people in the same situation. The light is only recognized in the darkness.”

A warrior who had vanquished all comers in a lifelong battle for truth was given one more corner of truth to uncover. The world would now see how unceasing diligence and unchecked devotion stands up to the ravages of pancreatic cancer.

With his diagnosis came a prognosis of months. Many miracles contributed to the extension of life that he was given, the extension we all were given. Credit is due to his children — his daughter Tzippy, his sons Mordy, Yitzi, and Moishy, and their respective spouses — for leaving no stone unturned in keeping him alive, allowing his light to shine forth to the world for three more precious years. He loved them unconditionally. “Kulam shavim l’tovah,” in his own words.

Tzippy recalls the day she drove her father to his biopsy. Her hands were shaking on the steering wheel, filled with dread. She could barely focus on the road. “And Abba was giving me a shiur on the pesukim of Yechezkel, regarding inheritance of the land at the end of days.”

When apprised of the severity of his illness, he had no complaints. “I had a good life,” he would say.

But there was one pasuk he repeated over and over.

“Ma betza bedami berideti el shachas…?” He wanted more time because his adventure was not yet complete. There was more to know, to produce, and to teach.

His wife went down to the basement in their Cleveland home, stood opposite the walls lined with close to a hundred binders of his chiddushei Torah and shelves full of his taped shiurim. She begged for time. For 70 years, he had made Torah come alive, in his heart and in the hearts of all those he had touched. Now, it was time to cash it all in, time for the Torah to keep him among the living.

And so, Reb Yankel’s adventure got an extension. Through the torturous treatments, appointments, and countless procedures, it continued unabated. From operating tables, in wheelchairs, and at his bedside. The beis medrash, as it had all his life, moved along with him.

For so long, he had been hidden in Cleveland. To facilitate treatments, he moved to his daughter’s home in Teaneck for the last two years of his life. It was now time for the East Coast to be warmed by his fire. Yeshivos, bungalow colonies, and the shuls of Manhattan and Teaneck were having a turn to hear his shiurim and to be inflamed by his undying passion.

“But now that it was decreed on me to battle for my life, I said to myself that perhaps now it is worth it. Perhaps the Creator of all healing will have pity on us and in the merit of disseminating my chiddushim… Hashem will renew my youth and send a refuah sheleimah.”

In these last years, he gave the world his sefer, Sha’ashuei Yaakov, a small sampling of the treasure trove stored in that basement. Rabbi Moshe Dovid Choueka has long been involved in preparing such types of works, but this experience was unlike any other. A man racked with pain fighting over every line. Every tzad, every kushya, every raaya. He let nothing go, never tired of seeking the light.

There were reasons he was always hesitant to publish his chiddusim, and in talking with Rabbi Choueka, we hit on another explanation. To Rav Yankel, nothing was ever finished. There were sevaros he discussed for 50 years with the same vigor and freshness as in its moment of origination. When Torah is living, understanding can evolve for infinity. Perhaps the finality of publication had always been too much to bear.

A year and a half ago, I spent a Shabbos in Mordy’s bungalow colony. They were celebrating their annual Siyum Hashas, divided among the members the summer before. A beautiful kiddush had been prepared outside, while Reb Yankel sat hunched in a corner of the shul, freezing cold on a 90-degree day with a towel wrapped around his head. The honor of saying the Hadran to mark the occasion was given to him. He shuffled over to the bimah and began to talk in a low voice. And then the Torah took over. He stood up straighter and his voice began to boom. For 20 minutes this went on. But for the fear of cold cholent, I am convinced he would still be standing there.

“I have ten terutzim to this kashye on the Rambam! Do you guys hear the vort?! Listen to this pshat, fellas!”

Devarim nifloim ad meod! There it was — the four words that were the soundtrack of my youth and the soundtrack of a life. The cancer had no chance of ever taking that away. His wife’s plea had been answered in full. The Torah was giving him life.

“I have special hakaras hatov to Rav Nosson Tzvi Baron who advised me and encouraged me to accept on myself to learn each day at least for an hour. And this was for me a great aliyah.”

The All-American boy had reached his potential. And nothing anyone did to get him there was ever forgotten. His father’s tears, his rebbeim believing in him, the bochur who took him under his wing, his loving wife and children, and every one of the people he had connected with through Torah. And the man who learned around the clock remembered to thank the rebbi who had convinced him to start with just one hour, almost 70 years before.

His wife ended our conversation with a request, the same one his children made. “Yankel would have only agreed to publicizing the story of his life if it increased kavod Shamayim. If everyone who reads this would find ten more minutes to learn, or to daven, or to do the will of Hashem, it will be worth it.”

I said I would try to find the space. But Ruthie got the last word. “Don’t try. Just put it in.”

I have talked to many talmidim over the last few weeks, hunting for stories of Reb Yankel’s youth, his struggles, and his rise. It is the easiest way to frame a life, to illustrate greatness, and to recreate the flavor unique to him alone. Through a man’s own history, you will get a glimpse of what drove him.

But then I hit a brick wall. Chavrusos who sat with him for ten years couldn’t recall patches of small talk. It was astonishing. Reb Yankel told no stories, and yet the depth of the connection they forged with their rebbi was endless, the texture of the love they shared so rich.

This was his legacy. He had the softest heart and the gentlest soul. His bright-eyed optimism found good even in the places most difficult to look and he summoned laughter even from those mired in paralyzing sadness. And all that he achieved and all that he gave came solely from the joy he found in his lifelong obsession. With the love of his life, he gave us all his whole heart, and with his unbroken connection, he connected us all.

On this past 28 Teves, the very same yahrtzeit of his great rebbi, Rav Elya Meir Bloch, Reb Yankel too was called home. As the aron made its way to Har Hamenuchos, a brilliant sun gave way to a sudden pouring rain. With heavenly inspired tears, this sefer Torah had begun to be written, and with tears from the heavens, the leibedige sefer Torah returned to the Aron Kodesh on High.

And before the boy from Chicago left us, he made sure to tell us one more time that we all can, too.

“And I give a good piece of advice to all who read this sefer, that he should accept on himself to learn each day a number of minutes that he knows he can stand by. And this should never be missed. From this he will be zocheh to a great aliyah with the help of Hashem.”

With just a few extra minutes every day, another adventure can begin.

And one more Jerry can become Hagaon Hagadol HaRav Yankel.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 848)

Oops! We could not locate your form.