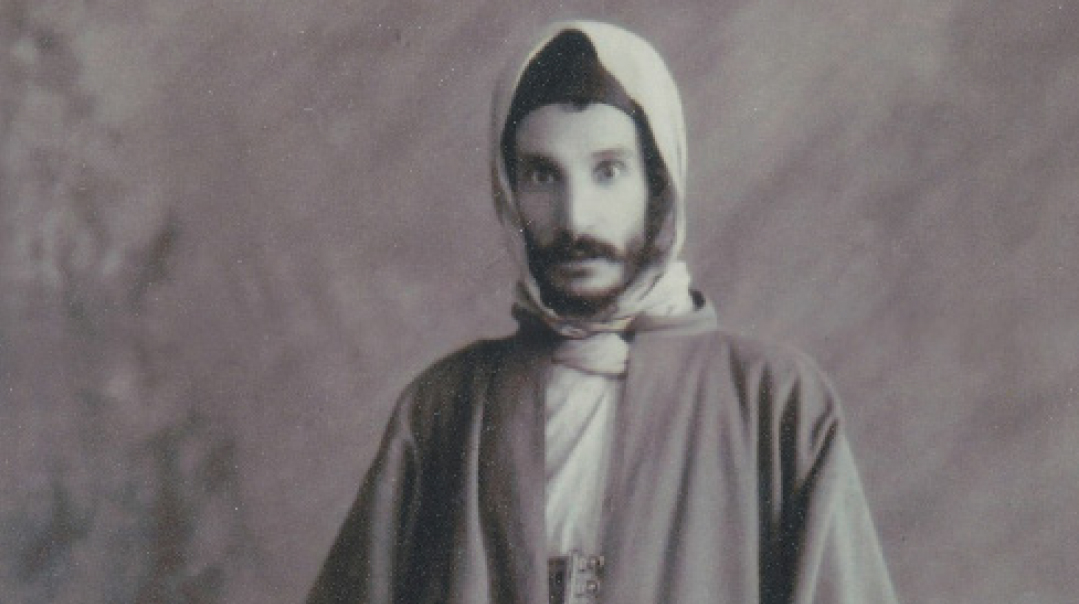

The Baba Sali’s Best-Kept Secrets

The Baba Sali's confidant finally reveals his secrets

Photos: Itzik Balnitzky, Rashi archives, The private archive of Rabbi Aviel Chaim Houri, Mishpacha archives

The sign on the door of the opulent villa in Ashkelon, Israeli’s southern seaside town, reads simply “Golan Family.” The large living room, comfortable sofas, and artwork adorning the walls are all tasteful and obviously expensive, befitting one of the country’s most successful and top-billing lawyers.

But downstairs, there’s a secret. A shrine of sorts, created by attorney David Golan’s alter ego. In the courtroom there’s no hint to his other life — scholar, talmid chacham, and the longtime personal confidant of Rav Yitzchak Abuchatzeira, the Baba Sali ztz”l.

His inner circle knows about this basement, although he doesn’t publicize it, and he rarely speaks about his years-long relationship with the Moroccan tzaddik, mekubal, and miracle worker who came to Eretz Yisrael in 1964 and settled in Netivot, where he was buried after his passing 20 years later.

“Good luck if you can get some good stories out of him,” an Abuchatzeira grandson tells us earlier. “He doesn’t like to talk, but he remembers everything. You can trust everything he says. But he never speaks publicly about this part of his life.”

Maybe it was because 35 years had already passed, maybe it was because he feels that some people are distorting the tzaddik’s reputation, maybe he was feeling like the time had come to reveal his stories and I happened to contact him at the right moment — whatever the case, when we meet David Golan, he’s in a chatty mood and happily gives us a tour of the basement shrine.

Climbing down the 15 steps is like being transported to Morocco. Unlike the sleek, modern furnishings upstairs, here the walls are covered with burgundy and gold tapestries, there are upholstered benches against the walls, couches with exotic throw pillows, and an assortment of traditional musical instruments. David explains that occasionally players from Andalusian orchestras come here to the basement. They sit for hours playing and composing songs in Arabic.

“But you’ve come to hear about the tzaddik,” he says decisively.

For a moment it seems as if he’s pulling aside a mysterious curtain, giving us an inside view of one of the greatest gedolim of the past generation.

David Golan was born in 1950 in the town of Erfoud, Morocco, where the Baba Sali’s brother, Chacham Yitzchak Abuchatzeira was the kehillah rav. Erfoud was a relatively modern city, with wide roads, electricity, a modern hospital, efficient water supply, and, with over 3,000 Jews, many shuls. By the end of the 1960s, no Jews remained in the city.

“The Baba Sali used to visit the city from his residence in the town of Risani, which was about 12 kilometers away,” Golan recalls. “And every time he visited, the entire community would come out to greet him. We children of the Talmud Torah used to hang around for hours just to catch sight of him stepping out of his vehicle and entering a house. That was all we were able to see.”

At the time, Golan had no connection to the Baba Sali, but says he was in the same class with his grandson, Rav David Abuchatzeira of Nahariya. His brother, the Baba Elazar ztz”l, was a few classes above them.

David Golan’s family moved to Israel in 1963, and he enrolled in Yeshivat Porat Yosef in Jerusalem, where his clever, sharp mind was noticed by Chacham Shimon Ba’adani and Chacham Shalom Cohen. Eventually he left the yeshivah and studied mathematics and physics at the Hebrew University, moving over to law and eventually becoming an attorney.

But before that, his connection to the Baba Sali was cemented.

“He made aliyah in 1964, the year after we did,” says Golan, “and I was a good friend of his son, the Baba Baruch — and that’s how it all started.”

The Baba Sali first settled in Yavneh, and then moved to Netivot in 1970, where he had a steady stream of visitors — chassidim, roshei yeshivah, Sephardim — anyone who sought his unique counsel. “Because I was a close friend of Rav Baruch, we would visit the Baba Sali in Netivot at least once a week. We would hear divrei Torah or divrei mussar, or celebrate with him.

“The Baba Sali didn’t know my father, but he surprised me by telling me he knew my grandmother, Leah Hadas Saliman a”h. She was the midwife when he was born, so maybe that’s why he took a liking to me and let me into his confidence.

“Look,” he continues, “I know everyone wants to hear miracle stories, so I’ll tell you a story I wouldn’t have believed had I not seen it with my own eyes.

“It was in 1973. I was still a bachelor, and every time I visited the Baba Sali, he’d ask me if I had gotten married yet. The truth was that I was about to get married, when tragedy struck the family. My future father-in-law was a guard at the Mekorot water company, but because he was shomer Shabbat, he couldn’t drive home when his watch was over on Friday evening, so he’d stay there until Shabbat was over.

“But one Motzaei Shabbat he didn’t return home. After a few days he was declared missing, and although soldiers and local citizens searched for him, they didn’t find a single clue. So we decided to push off our wedding until this was resolved.

“This continued for a year. In August 1974, the Baba Sali traveled to France, and on the day of their return flight, I went to the airport with the Baba Baruch and his mother, the Rabbanit, to meet them. Rav Baruch had a permit to go onto the tarmac to bring his father down.

“On the way, the Rabbanit decided to pay a visit to the Baba Sali’s nephew, Rav Avraham Abuchatzeira, who was the rav of Ramleh. [His father, the Baba Sali’s brother Chacham Yitzchak, settled in Ramleh after leaving Erfoud, where he was rav for 20 years before his death in a traffic accident on his way back from visiting his brother, the Baba Sali, in Netivot.] We sat with Rav Avraham and told him that we were on the way to the airport to greet the Baba Sali, who would be arriving at ten o’clock that night.

“Rav Avraham held up his hand. Suddenly I saw him pull out a pencil and write ‘10’ on a scrap of paper. Then he crossed it out and wrote ‘12’ in its place. I didn’t think anything of it at the time. Anyway, we arrived at the airport, but the Baba Sali wasn’t on the ten o’clock flight. Rav Baruch contacted his sister in Paris, where the Baba Sali was staying, and discovered that there had been a mix-up at the airport and they put him on a later flight, which landed at exactly 12 midnight.

“Suddenly I remember how Rav Avraham wrote 10 on the paper, crossed it out, and wrote 12. I started trembling all over. The Baba Sali came out, and we drove back to Netivot, where there was an entire seudah prepared. We sat down to eat — it was about 4 a.m. — and the Baba Sali asked me again if I had gotten married. I told him that my kallah’s father was still missing.

“The tzaddik then told me that while in France, a father whose daughter had gone missing came to him. ‘I promised him that b’ezrat Hashem she would be found,’ the Baba Sali told me, and indeed she was. As a gift, the father gave the Baba Sali a gold watch and cufflinks. The tzaddik gave the watch to Rav Baruch and the cufflinks to me.

“Then he turned to me and said, ‘B’ezrat Hashem, your father-in-law will be found today.’ I thought the rav was overexcited because of his trip. My father-in-law had been missing for a year.

“I returned home around seven in the morning, and a little while later my future wife came knocking at my door. ‘David, they found father!’ What happened? A tractor digging near the moshav where he lived unearthed a corpse, and the identity card in its pocket proved it to be her father.”

Over the years, David Golan would often pay the Baba Sali personal visits. “His house was a simple Amidar government apartment,” Golan remembers. “Outside there were always groups of people waiting for brachos. He had a gabbai named Eliyahu Alfasi who managed the line, but when I came, he let me right in. When Alfasi wasn’t there, the Rabbanit told the Baba Sali that I had come, and I was instantly ushered in.

“He always sat in an armchair, either with his legs elevated, or else crossed in the oriental position. He always sat with a sefer. Always. When I’d come at night, and that often happened, he often had a hilula of a tzaddik to celebrate. He commemorated them on his own, tzaddikim whose names I had never even heard of. It wasn’t exactly a party, though. He would read the Zohar, beside him a plate of refreshments and some arak — although he never actually ate any of the refreshments. In fact, you can’t really use the word ‘ate’ in connection with the Baba Sali at all. He barely tasted anything. His entire essence was spiritual. You could see that he was nourished entirely by spirituality. You couldn’t see any less food on the plate after he had supposedly eaten.”

Golan remembers that the Baba Sali actually fasted most of the year. “He did what we Moroccans call taanit hafsakah. That’s a fast of six days consecutively. It would start immediately after Melaveh Malkah on Motzaei Shabbat, and continue until Friday afternoon, when he would take something to avoid entering Shabbos hungry. And the truth is that he wasn’t the only one who did it. Other Moroccan tzaddikim would do it as well. ”

But despite the fasts, the Baba Sali was known for the hilulas and seudos that he would conduct in honor of departed tzaddikim of previous generations — his ancestors of the house of Abuchatzeira, the Ari Hakadosh, and many others. Of course, Reb David reiterates, he himself barely touched the food. But the table was loaded with choice delicacies, and he would pour out large cups of arak to his guests in honor of Mashiach.

Reb David, who was present at dozens of these seudos, tries to convey the scene. “There were usually between 15 and 20 people, each one hoping the tzaddik would pour out arak for him personally and give him an accompanying blessing of ‘brachah v’chayim.’ But there was a rule — every glass had to be accompanied by a piyut. You could only down your cup after a piyut was sung.”

Piyutim were a central element in the house of Abuchatzeira. His grandfather, the Abir Yaakov, wrote an entire book of book of piyutim entitled Yagel Yaakov — every piyut filled with midrashim and reflections in mussar.

There’s a chilling piyut, which tells of the execution of his brother, the mekubal Rav David Abuchatzeira Hy”d, who was murdered in 1920 during an uprising against the French Protectorate, when the Abuchatzeira family was suspected of collaborating with the French.

“My father witnessed the execution,” says Reb David. “He saw ‘Ateret Rosheinu,’ as Rav David was called, dragged into the town square on Shabbos. They tied him up together with two more Jews and fired a cannon at them. The three bodies were torn into thousands of pieces. I’m named after him.

“Every time we sang this piyut, no matter how many times we sang it, the tzaddik would burst into bitter tears,” Reb David continues. “Back then the piyut hadn’t yet been written down, so very few knew it. Rav Baruch did, and I learned it from him. The Baba Sali used to ask me to sing it, but I would try to wriggle out, because I knew how hard it would be. But sometimes he insisted, and so I would sing the words that described the execution. It would send a shiver down my spine.”

For many petitioners, the Baba Sali made demands, speaking in either Arabic or Lashon Kodesh, depending on the visitor. “His first question was if you kept Shabbat. Regarding Shabbat, tefillin, and taharah, there were no compromises,” Golan says. “And he was very specific, warning that ‘if you usually do A, B, C, and D, make a resolution to stop. Otherwise, the brachah I’m giving you will be meaningless. Take it upon yourself to increase your observance, and Hashem will help you.’

“But he didn’t give mussar to everyone — only those who were close to him. The rest of the time he was the best defense attorney I knew. You couldn’t utter a bad word about anyone in his presence, irrespective of whether he was religious or not. If you told him, ‘So-and-so is mechallel Shabbat,’ he would tell you, ‘HaKadosh Baruch Hu will make him do teshuvah.’

“And it wasn’t just criticism of Am Yisrael that he couldn’t tolerate, but also criticism of Eretz Yisrael. He loved Eretz Yisrael in his heart and soul. Everything he saw here was good in his eyes. He wouldn’t let you utter one word against the country.”

For Reb David, special treatment meant he had access, but the Baba Sali greeted him the same way he greeted everyone who entered his home.

“When I would come in, he didn’t budge, just sat in his place with his eyes lowered. He smiled and said, ‘Baruch haba.’ And of course there were refreshments. When someone close to him came, they brought refreshments, sometimes even a meal.

“Then I would sit down next to him. If I’d come on some specific issue, I’d begin the conversation while he would listen intently, eyes lowered. If he looked at me for more than one second during a long conversation, I was thrilled.

“Sometimes he would become silent, lowering his head and making figures in the air with his finger. He did that when he was thinking — but to this day I can’t tell you what those gestures meant. But when he started drawing his shapes in the air, you couldn’t move or disturb him at all. Not until he had finished. It could take up to ten minutes or a quarter of an hour. And then he would resume the conversation.”

The Baba Sali was known as a great oheiv Yisrael, someone with unconditional love for every Jew. But according to Golan, not every meeting went smoothly. Sometimes he was just too tired, or sometimes he disliked what a person was saying. “Then he would put down his head as if he had fallen asleep, and you understood that you were expected to leave the room. When that happened to me, I would go up to him, kiss his head, and leave.

“Once I came with someone, and the Baba Sali ‘fell asleep.’ We left the room, and then he sent Alfasi to call me back. He asked, ‘Who was it who came with you?’ and I understood everything.

“But that was rare. I can’t explain it. He had powers that I couldn’t understand. Without raising his eyes, he could tell who was sitting opposite him.

“Every time I visited, it was always the same — I was overcome by awe and fear of his kedushah. But then, once I’d sit down next to him, I’d gradually relax and feel so blessed to merit to be in his presence. But at first, I was always extremely tense. That’s what it’s like when you’re sitting with a person who you have no idea how to define, don’t even know in what parameters to define. You’re sitting with a person of flesh and blood, but his whole essence is Torah and kedushah.”

According to Golan, the visitors the Baba Sali really appreciated were rabbanim and talmidei chachamim. “When they came he was very happy. ‘Sit, baruch haba.’ He would knock on the table, which was a signal that the Rabbanit or the gabbai should come. When they saw people with him, they would quickly go to bring refreshments.”

Reb David chooses his words carefully when he speaks about their conversations. There are many things he obviously doesn’t wish to talk about. “There was once a situation — and when I say ‘a situation,’ I mean that I don’t expect you to ask what it was — where I compared him to Yaakov Avinu. And then he started yelling — how could I dare compare him to Yaakov Avinu! He used an Arabic expression about himself, the closest translation of which is ‘I’m full of sin, human filth’ — how can you dare compare me to Yaakov Avinu, expect me to behave like Yaakov Avinu? I was startled, and he burst into tears.”

Reb David mentions this because, he says, that’s really how the Baba Sali saw himself. “It was a different world then. He was like the chachamim of old, a Jew who was perfectly content to sit within his four amos with his Zohar and learn. He didn’t expect any followers and certainly didn’t ask for any. From his perspective he was a simple man who just did what he was supposed to. He did his best to honor Hashem privately, in his own way, without any public display of avodas Hashem.

“And that’s why he didn’t write kamayot either. Never. If someone ever tells you that he has a kamaya from the Baba Sali, you know that it’s a fraud.”

Still, there are stories about the Baba Sali’s holy water.

“I’ll tell you. One time — I even remember the date, January 26, 1978 — it was Thursday, and I had just returned from abroad, so I went to visit him. My brother Yosef a”h went with me. In the middle of the conversation I asked the Baba Sali what brachah he said together with the water that he gave people. He answered very sternly, in Arabic. ‘These fools think I have something. What do I have? I have nothing!’ He used words that I don’t dare translate. ‘I’m the worst of men, how can I give brachot to Jews?’ When I asked him about the holy water, he explained that their power lay only in people’s faith that it would help them. ‘It’s emunah that grants the water its power, it’s the emunah that’s making miracles.’ ”

While the Baba Sali claimed that he was nothing, he had the power to literally shake the world. Reb David remembers one day when he was part of the inner circle joining family members for the afternoon meal. “We sat in this order: the tzaddik, Rav Baruch to his left, then the Rabbanit. On the right were some ten other people, among them his sons-in-law Rav Ariel and Rav Turgeman, as well as some guests. I sat opposite.

“What I can tell you is that we drank a lot. The tzaddik was happy and he was pouring us glasses of arak. He filled our cups to the brims. And the arak was the real stuff — strong. Nowadays I’d rather drink petrol rather than this arak, but when the tzaddik fills your cup, you don’t even think of refusing. When the Baba Sali offers you a cup, you have two choices, to commit suicide on the spot, or to drink. And by the Baba Sali, there was no such thing as drinking without an earnest prayer for the arrival of Mashiach.

“Aside from the tzaddik, who drank nothing, we were all pretty tipsy. And as he’s intoning, ‘Sheyavo Melech Hamashiach,’ his son Rav Baruch says in Arabic, ‘It’s due to Abba that the whole world stands. And if not for him, the entire world would be destroyed.’

“At that moment, everything in the room moved. The table, the bottles, the food, even the light fixtures. But I paid no attention to it — after all, we were all drunk. We didn’t make the connection. Later, Rav Baruch and I get in the car and start listening to the news — and then they announce that at exactly 2:15 an earthquake was felt in the area of the Negev. All over Netivot walls cracked and windows shattered. And I say to Rav Baruch: ‘That’s exactly when you told your father that without him the world would be destroyed.’ ”

The Baba Sali was perhaps most famous for his levels of kedushah, expressed by his stringencies in shmiras einayim. “Within the Abuchatzeira family,” says Reb David, “it’s believed that that was the secret of the Baba Sali’s strength. And I think it’s important that the younger generation learn from it.

“His eyes were always lowered, even when speaking with men. Usually his hand was on his forehead — that’s why in many pictures he’s shown with his hand raised. His eyes were the most precious thing in the world to him. Usually he didn’t look at anything. You sat with him ten hours — if he looked at you for more than a second, it was too much. His eyes were always lowered, so he should never be distracted.”

Reb David says his stringencies were almost superhuman. “No woman in the world was permitted to come close to him except his wife and daughters—even his granddaughters weren’t allowed to approach him. Even when they were presented to him — ‘this is your son’s daughter,’ ‘this is your daughter’s daughter’ — they weren’t allowed to approach him.

“In all my years close to the Baba Sali, I remember only one instance when a woman entered his room. It was the wife of one of the biggest gvirim in the Jewish world, a multimillionaire of great influence, and she wouldn’t back down in her desire to speak with him. It became a sort of mini diplomatic crisis. One of the government ministers approached me and asked, ‘What can be done? It would be a shame to lose his support.’

“My sins I’m recounting today,” Reb David continues. “In the end I went to the Baba Sali and I told him that this woman dreamed that she had to receive a brachah from him in person. He was quite agitated. In the end he agreed on two terms: that we cover his hands and he lower his face. She entered the room for one moment and then left.”

The Baba Sali traveled a lot though, passing through airports on trips abroad. How did he protect his vision in such crowded, public places?

“I know this sounds unbelievable, but you’ll have to take my word for it,” Golan recalls. “I met him at the airport on three different occasions. I can’t explain it, but every time he arrived, you felt that the whole country had ground to a halt. The airport suddenly became empty.”

Reb David remembers a particularly difficult event, on Chanukah in 1979, in which he brought the Baba Sali to the King David Hotel in Jerusalem for a meeting that included Prime Minister Menachem Begin, billionaire Nissim Gaon, president of the World Sephardic Federation, and other power brokers.

“I can’t reveal the details of why the tzaddik had to attend,” says Reb David. “I’ll just say that he was strenuously opposed to going. But there was no choice. It was an important mission for helping a Jew that he knew.

“I accompanied the Baba Sali as he stepped into the enormous lobby. He was taken aback by the opulence of the place and he asked me: ‘What is this?’ I told him it was a hotel. He said, ‘This is a hotel? This is a country!’ He remembered small hotels from his days in Morocco — nothing so extravagant.

“I took him upstairs in the elevator, to the suite. On the way, he asked me, ‘Where are we going?’

“I told him, ‘We’re going to the ninth floor.’

“He was astonished: ‘In Jerusalem they’ve built nine floors?’

“But the reason I’m telling you about this whole secret event is to teach the younger generation what the meaning of shmirat einayim really is. He entered the room — in addition to Menachem Begin and Nissim Gaon, there was attorney general and later president of the supreme court Aharon Barak, and the director-general of the Justice Ministry.

“And the tzaddik, clasping my hand, just said ‘shalom’ quietly, and that was that. After that he dropped his eyes and didn’t raise them for a single moment the entire evening while he just whispered to himself. Everyone was sitting in awe of his frail, holy figure, and the truth is, I felt terrible for having dragged him there.”

Many people tried to give money to the Baba Sali, both for himself and as tzedakah for all the struggling people who passed his threshold.

“Many of the people who came to him left money on his table,” Reb David explains, “but he had no conception of amounts. I don’t remember him ever dealing with a bank account.

“But I do remember one time when Nissim Gaon came to him along with an entire VIP delegation. In the middle of the meeting Gaon reached into his pocket, pulled out a checkbook, filled in a donation of $50,000, and gave it to the tzaddik. What was more amazing, though, is that the tzaddik didn’t even glance at the check. Believe me, if he had written $1 instead of $50,000, he would have received the same treatment.

“Another time Nissim Gaon bought him a car. You should have seen how the Baba Sali reacted — he was in pure anguish. ‘I need a car?! What, I take trips?! Give it back!’

“They also bought him a luxurious house, but he refused to move there. He only agreed when they built a small cell for him with a cot inside the house — he agreed to move into that. Even the shul built for him by a good Jew named Avraham Almasari he didn’t want. When we told him, ‘We’re planning a shul,’ he was furious. He used to say, “Is this what our forefathers left us?! Palaces and fancy buildings?! They left us only the Torah and taught us about avodah in modesty and yirah.

“After the Six Day War there was a certain donor who bought a plot in the Old City, where Yeshivat Porat Yosef is currently located. He wanted to build a house for the Baba Sali there. But the tzaddik wouldn’t agree under any circumstances. In the end, this donor bought him a small apartment in the Mattersdorf neighborhood. The house was usually empty, but every Rosh Chodesh the Baba Sali would come to Jerusalem and hold a seudah there. Always in honor of someone, in honor of a tzaddik of family ancestor. And there were always crowds waiting for us when we arrived — rabbanim, even Satmar chassidim.

The Baba Sali’s health gradually deteriorated, primarily due to his prolonged fasting, which ruined his intestines.

“Our last conversation was a few months before he passed away,” says Reb David. “Because he hardly walked, we had to massage his legs to release the blood flow. I was the only one who could do it. I used to sit and massage his legs for hours. He was very weak and hardly spoke, but I heard him blessing me in Arabic the whole time, ‘May HaKadosh Baruch Hu protect you and may the zechut of my ancestors light your path…’ ”

But the most shocking story is really a postmortem. David Golan walks into an adjoining room and returns with some medical documents. He coughs briefly and then begins the story.

“In November 2014, I was diagnosed with leukemia. It was pretty far advanced. I was hospitalized at Tel HaShomer, and they explained that they would give me six consecutive chemotherapy treatments. Only then would they decide if I needed a bone marrow transplant. In my heart of hearts, I said goodbye to the world.

“One night in the hospital, I had a dream. I saw myself in the old terminal of the airport, and there, having landed, was the Baba Sali with his son, my good friend Rav Baruch. And I say to Rav Baruch in tears, ‘Please ask your father to send me a refuah.’

“At four in the morning, they wake us up for blood tests. The dream is over. At eight o’clock the doctors drop by. Professor Davidovitch comes and tells me, ‘Mr. Golan, we’ll get back to you in two hours.’

“I ask, ‘What’s the delay?’

“He says, ‘We got the results of your blood test, and we just want to make sure there isn’t some mistake.’

“And then he told me, ‘This is the first time in the history of this ward that we got results like these after just two chemotherapy treatments.’

“And I’ll tell you one more story: I used to take my oldest son with me to visit the Baba Sali. I tried to convince him to kiss the tzaddik’s hand, but when the moment came he would shy away. One time, though, he fell asleep, and so I carried him on my shoulder and went in to the Baba Sali. I put the child on his lap and said, ‘This is my son, give him a brachah.’ He pulled out his tallis, covered him with it, and gave him all the brachos in the world.

“And so, when my son grew up and began growing distant from Judaism, I wasn’t too worried. ‘That’s the Baba Sali’s problem,’ I said. And then, in 1997, I was in Morocco at the kever of Rav Shmuel Abuchatzeira ztz”l. I spoke with my wife on the phone, and she said, ‘David, you won’t believe it, Oren has been chozer b’teshuvah.’ Since then he’s a completely different person. He’s editing the works of Rabbeinu Abravanel, and he goes to the mikveh every day.

“I don’t know how I merited it,” attorney Golan admits, “but the power of the tzaddik still accompanies me in every step in my life. Zechuto yagen aleinu.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 781)

Oops! We could not locate your form.