The Art of Defense and the Scales of Justice

| September 9, 2025We believe the earthly court doesn’t have the final say; there’s a Ribbono shel Olam Who is the Ultimate Judge

Working as a criminal defense lawyer for decades has afforded me some insights into the justice system, and thus a unique perspective on the Yemei Hadin.

I’m frequently asked, “What do you do if your client is guilty?”

Growing up, my children simply knew, “All of Daddy’s clients are innocent.”

And in the American justice system, they are. Our system isn’t about whether someone did the act, but whether the government can prove it beyond a reasonable doubt. If it can’t, legally, the person is innocent, regardless of what actually transpired. In any event, everyone deserves representation, because mitigating circumstances may exist, even if wrongdoing occurred.

For a religious Jew, the concept that the guilty may get off in court should be more palatable. I know a non-Orthodox New York State Supreme Court judge who teaches comparative law, focusing on American law versus Jewish law. I always told him he’d never truly grasp the most fundamental difference between the two justice systems because concepts like Hashgachah Pratis and Olam Haba were not foundational truths for him.

Consider the Gemara in Sanhedrin (17a), which states that if a defendant in a capital case is on trial and the entire beis din votes to convict, halachah dictates that the beis din must acquit. This stands in stark contrast to the American system, in which a unanimous jury is required for conviction.

Or think about the requirement that a beis din can only impose the death penalty if two valid eyewitnesses warned the accused before the act. With such requirements, how likely was it that the death penalty would actually be imposed? Not very often. Indeed, Rabi Elazar ben Azariah (Makkos 7a) considered a beis din that executed more than one person in 70 years a beis din katlanis — a “killer beis din.” In America, thousands are on death row, with about 25 executions annually.

What accounts for this vast disparity? A beis din is primarily concerned with not punishing the innocent. Better to let many guilty people go free than wrongly convict one innocent person. Why? Because we believe the earthly court doesn’t have the final say; there’s a Ribbono shel Olam Who is the Ultimate Judge. Guilty parties will ultimately receive their just desserts, regardless of what happens in our earthly courts.

In a secular court, especially from a nonreligious judge’s perspective, the court system is the final arbiter. If a murderer escapes justice, he’s escaped entirely. How then do we protect the truly innocent? By providing everyone, even the possibly guilty, with strong procedural protections.

Many people, even prosecutors, miss this. So when someone “pleads the Fifth” (invoking his right against self-incrimination), the natural reaction is often, “Aha, he must be guilty!”

But the Fifth Amendment was actually designed to protect innocent people from making a statement that could accidentally mislead someone into thinking they’re guilty. These procedural safeguards, however, only go so far. If the innocent is wrongly convicted, which happens too often, it’s viewed as unfortunate but a casualty of the system.

So, would I represent someone I knew was guilty? Likely yes. You cannot have a criminal justice system that truly protects the innocent without providing adequate representation to everyone accused.

Oddly enough, most people only harbor these doubts when the accused is not close to them. As soon as a friend or family member faces accusations, those questions vanish, and they demand the best representation, even if they suspect wrongdoing. (“After all, it’s not like he killed someone.”)

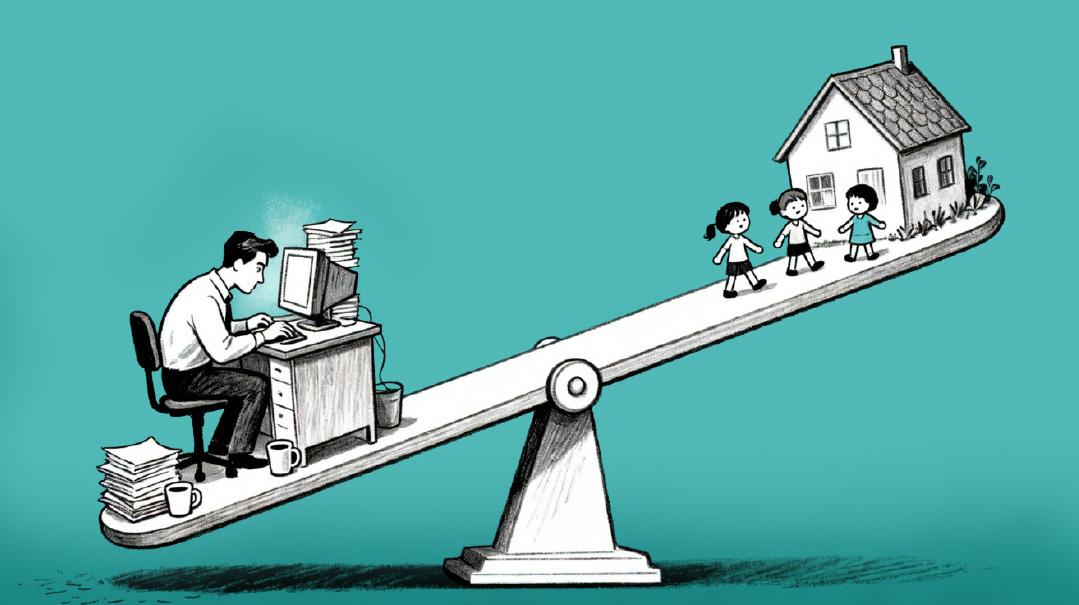

In truth, we must all be “defense lawyers.” The Torah commands us to judge our fellow man favorably. This sometimes requires mental gymnastics to convince ourselves that what we thought happened really did not.

And when we act as defense lawyers on behalf of our fellow Jew, surely, we will invoke the strongest defenses on our own behalf, in the Court that really matters.

My Day at the Supreme Court

It was Erev Succos. I was putting the final touches on my succah when an unexpected email landed in my inbox from the Supreme Court’s Clerk’s Office. It took me a minute, but then it hit me: I had just been granted review by the US Supreme Court on the case for my client, McIntosh.

With over 1.3 million lawyers in this country, less than one percent argue a case before the US Supreme Court. But a quick check of the Court’s docket confirmed it: I was going to D.C.

Emails soon poured in from lawyers at big firms around the country congratulating me. Their real goal was to convince me to hand the case over to them. I politely responded that I planned on arguing the case myself. That made them lose interest immediately, though some warned I might not realize what I was signing on for.

In my view, I had certainly earned the right to see the case through. When McIntosh first came to me, he had been sentenced to 59 years in prison, ordered to forfeit $95,000 (plus his BMW) to the government, and pay $75,000 in restitution. Now, some eight years later, his sentence was down to 25 years, forfeiture to $26,000 (with credit for the BMW), and restitution only $4,500. A pretty good result, if I may say so myself. And now, the Supreme Court was going to decide if the government was entitled to any forfeiture at all.

I partnered up with an experienced Supreme Court practitioner, and my prep work began in earnest. I was advised to do several moot court arguments. My first one did not go as I’d hoped.

“Am I making a huge mistake?” I asked my wife later that day.

I was stumped by questions and fumbling for answers. I dug in, however, and by the time I flew to Chicago for my next moot court, I felt more at ease. A week before the big day, I did my final moot court at Georgetown University, and I was able to respond quickly to all the questions thrown my way. I was confident I could do this.

The big day arrived. I, along with several family members, made our way to the Court. Security was tight; no electronic devices were permitted. My brother asked one of the security guards if he could hire him for his shul, because not so much as a pin drop could be heard.

My case was called first. For 30 minutes, I was peppered with questions from almost every member of the bench. Six months later, the decision came down. I had now joined that exclusive club of lawyers who, like Abraham Lincoln and founding father John Marshall, had argued one case before the Supreme Court and lost.

Was it still worth it? Definitely. Would I do it again? Absolutely.

The lesson? We cannot enter the Day of Judgment without contemplating and preparing. When it comes to our lives, we can’t afford to be in the Lincoln-Marshall club.

The Master Recording

As criminal defense evolves, technological advancements, rather than benefiting defendants, are increasingly formidable adversaries.

Many cases now involve technology-based evidence such as “cell site data.” The prosecution uses cell phone data to track movements made by defendants, providing strong corroboration for the testimony of their cooperating witnesses. Often, a defendant’s WhatsApp conversations, which containing admissions that the defendant never dreamed would be uncovered, become available to the government. The defendant unwittingly loses the security of encryption when he backs up the information on his phone to the cloud.

The Chofetz Chaim in Sheim Olam (end of chelek alef) pondered why humanity thrived for millennia without modern technology, only to experience a sudden explosion of advancement, which in his time included cameras and phonographs. He explained that in prior generations, people’s emunah was strong enough to accept that an “All-Seeing Eye and All-Hearing Ear” existed in Heaven, and they conducted their lives accordingly.

But as the generations progressed and emunah weakened, Hashem then instilled in humanity the wisdom to invent devices like cameras and recorders. These inventions taught humanity that earthly events could be recorded for posterity. As subsequent generations further weakened in their emunah, Hashem continued to advance technology.

At some point, we will all face a trial in the ultimate courtroom Above. We cannot delude ourselves into believing that all the records from our lives will not be presented. Everything is recorded in the Heavenly “cloud.” If we wish to keep these records “encrypted,” the only true solution is teshuvah. Let us be grateful for this opportunity.

Admitting Guilt

As a result of his work as a Ground Zero first responder, Marty experienced health issues. It was doubtful the judge would send him to prison for tax evasion, despite his use of company credit for personal expenses. While Marty had many positive factors, it was crucial that the Court see him accept responsibility. The evidence was overwhelming, so going to trial was not an option. Marty agreed to plead guilty, but when it came time to tell the court in his own words what he had done wrong, he broke down. He just couldn’t bring himself to admit his guilt in open court.

Marty’s inability to admit guilt or accept responsibility is not uncommon. Even when we know we’re wrong, we have a hard time admitting it, and an even harder time doing so in public.

Contrast Marty’s conduct with ours on Yom Kippur when we recite the Vidui ten different times, sometimes at the speed of light. Why don’t we break down like Marty? Could it be that we’re giving little thought to what we’re really saying? If we put little to no feeling into it, we have no hesitation in making the admission.

If that’s the case, can we really expect to earn the forgiveness that deep down we are certainly hoping for?

Perhaps if we picked one al cheit, and we took Elul to focus on all the laws and nuances of this particular cheit. Then, at least when it came to this one al cheit, we would share the shame and regret of the Martys of the world.

If we do this, then hopefully the Ribbono shel Olam will see that we are on the path toward teshuvah, and we will be zocheh to be inscribed for the life we seek.

Yitzchok (Steven) Yurowitz is the owner of YurowitzLaw PLLC, a boutique litigation and appellate practice focusing on white-collar criminal defense, and a contributing author to New York Criminal Law (4th Ed.), a leading treatise on substantive criminal law.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1078)

Oops! We could not locate your form.