The Answers Man

While he views today’s massive crowds as a sign of blessing, he misses the unity that marked the Meron of his childhood — when there was one fire for everyone

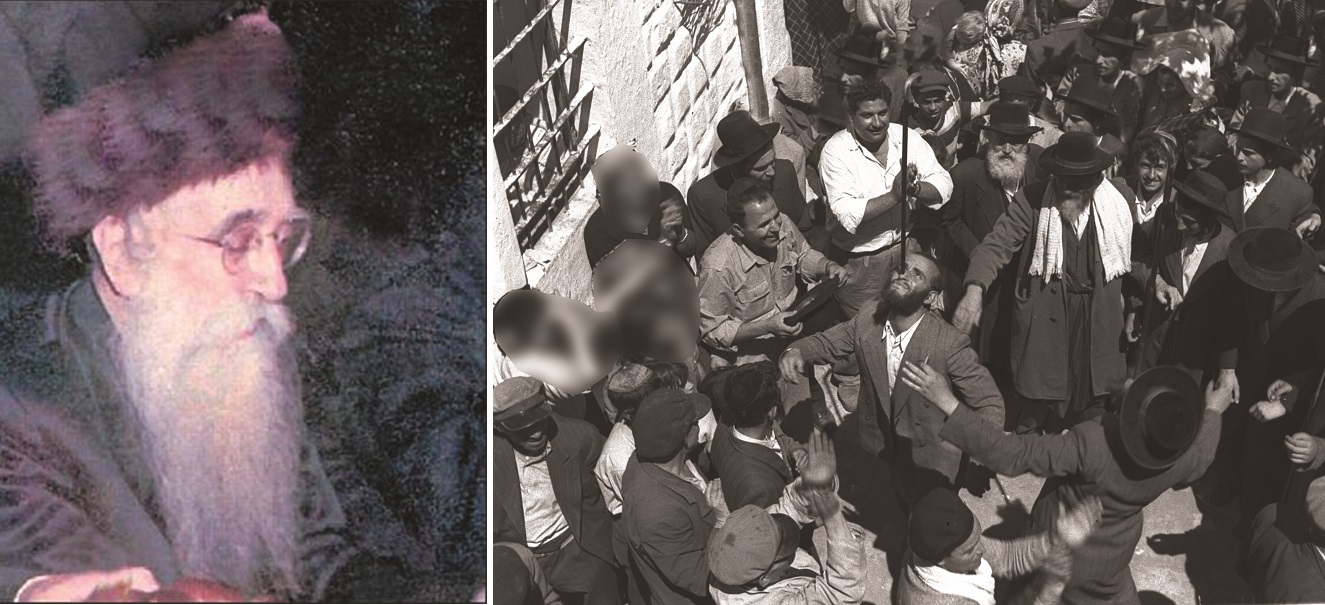

The family of Rav Mordechai Dov Kaplan, the rav of the Ari shul and the Old City in Tzfas, was entrusted with a sacred mission by the Rebbes of Ruzhin. Every Lag B’omer, he’d travel to Meron, to watch flames of joy and salvation overtake the dark hilltop. And while he views today’s massive crowds as a sign of blessing, he misses the unity that marked the Meron of his childhood — when there was one fire for everyone

It was Erev Lag B’omer, 1945. The Jews of Tzfas had made their yearly journey up the isolated Mount Meron, and were now convened on the roof of the tziyun of Rabi Shimon bar Yochai.

Rav Avraham Leib Zilberman, rav of Tzfas, stood with the torch in his hand, ready to carry out the task entrusted to his family by the Ruzhiner dynasty — to light the fire in honor of Rashbi. But the sky was still shrouded in darkness, with no moon in sight. According to tradition, the fire was only lit when the moon grew visible.

The people of Tzfas and their rav stood and waited. The hour grew later; nine o’clock came and went. Still no moon. A low murmur overtook the crowd: “Let the rav light already, there is no use waiting.” But one of the assembled, a mekubal from Tzfas, silenced the grumbling.

“The rav should not be pressured,” he said. “Wait until the moon appears. Perhaps it is a hint from Above.”

At 9:50 the news rippled through the assemblage on the mountaintop: Adolf Hitler had killed himself in his Berlin bunker. A few minutes later, the moon emerged, and Rav Avraham Leib lit the fire. Finally, the lonely hill erupted in glorious song. Lag B’omer had arrived, bringing with it salvation and a rare glimpse of Divine favor in the darkest of times.

Honey Cake and Dancing

Rav Avraham Leib is no longer alive, but his grandson, Rav Mordechai Dov Kaplan, still carries on the family legacy of leadership in the holy city of Tzfas. His father, Rav Simcha Kaplan, married Hadassah, the daughter of Rav Avraham Leib Zilberman, and took on the role of rav.

Rav Mordechai Dov, the next link in the chain, currently serves as rav of Tzfas’s Old City and Ari shul, and the head of the Yeshivas Tzfas Kollel in the Old City. He is also a member of the “Committee of Five” — a group of five men that oversees the kever of Rashbi in nearby Meron — and as such, lives with both the memories of Lag B’omers past and the imperative to ensure that the holiness of the site is perpetuated in the future.

“From the age of three, there wasn’t a single year that I haven’t been here on Lag B’omer,” he says. As he leads us through Meron, his memories of those consecutive years by Rabi Shimon come to the fore.

Today, Lag B’omer in Meron includes mass transport, blaring music, a smorgasbord of food and drink, and government involvement. But the old-timers remember a different Meron. When Reb Mordechai Dov asked his mother how the hilula was celebrated in her childhood years, she painted a scene rich in detail: “In the evening, after Sefiras Ha’omer, my grandfather Rav Raphael Zilberman would light the fire on the roof of the tziyun. After that, they would dance for about a half hour, and then they would go into the tziyun and learn passages from the Idra and the Zohar. Then they’d eat a bit of lekach [honey cake], drink a bit of whiskey, and return to the roof to dance some more.

The dancing was spirited, even without any musical accompaniment. After another half hour of dancing, they went back in to learn. This pattern repeated itself over and over again. They learned downstairs and danced upstairs, alternating a half hour at a time, until sunrise.”

A Can of Whitewash

A generation later, the celebration was larger, but still unpretentious. “My grandfather, Rav Avraham Leib Zilberman, would come to Meron five days before Lag B’omer,” Reb Mordechai Dov Kaplan says, repeating the family lore. “The trip was made by donkey. He would stay in one of the rooms above the tziyun and use those days to prepare himself for the moment that he would fulfill the holy mission of lighting the Lag B’omer fire.”

Traditionally, the honor of lighting the fire on Mt. Meron had been reserved for the Rebbes of Ruzhin. During Rav Zilberman’s life, the Rebbes lived abroad. As a Ruzhiner chassid and the rav of Tzfas, he was entrusted with the sacred task.

Dancing and learning, learning and dancing. The old-timers of Tzefas and the previous Boyaner Rebbe felt the holiness of the day.

In 5708/1948, Reb Avraham Leib Zilberman passed away at the age of 58. For two years, his son Reb Mordechai Dov (Berel) ztz”l managed the rabbinate and lit the fire.

“My uncle Reb Berel was the spirit of the hilula and of Meron,” says Reb Mordechai Dov, who is named for his uncle. “On Lag B’omer he would dance in the courtyard of the tziyun all day, and throughout the year, he would take care of the kever and the kevarim of other tzaddikim buried in the Galilee.

“Here,” Rabbi Kaplan says, pointing as he takes us through the tziyun. “This room belonged to Reb Menashe Eichler shlita, the most veteran of the anshei Meron. He told me that he used to travel through the Galilee with my uncle Reb Berel to locate the ancient kevarim and refurbish them. One day, they were in Rosh Pinah, and when they were ready to return to Meron, Reb Berel turned to Reb Menashe and said, ‘What do say we walk back to Meron? We’ll take the money we set aside for our taxi, and use it instead to buy a bucket of whitewash. This way we can finally paint the walls of Rashbi’s courtyard.’ Rav Eichler agreed. For hours, they trekked up the hills to Meron, and arrived tired and sweaty — but pleased. When Lag B’omer arrived, the visitors would dance in a freshly painted courtyard, as befitted the honor of the great Tanna whose merit they sought.”

Reb Berel’s generation used to dance for 24 hours on Lag B’omer, almost nonstop, Rav Mordechai Dov remembers. “On the night afterward, after everyone had left, my uncle continued dancing with the cleaning crew. He was far from a simple man — he was a tremendous scholar and posek — but he also deeply loved Rabi Shimon bar Yochai, and he didn’t see it as beneath his dignity to dance and sing with all his might for Rashbi. For him, it was an honor.”

Jeep to the Top

As we ascend to the roof of the tziyun, Reb Mordechai Dov’s focus shifts to his father, Rav Simcha. Russian-born and Mir-educated, Rav Simcha Kaplan joined the Zilberman family in 5710/1950 upon his marriage to Hadassah. “On the fifth of Adar, at four o’clock, my parents’ chuppah took place,” Reb Mordechai Dov relates. Several gedolim of that generation were present, among them the Chief Rabbi Rav Yitzchak Eizik Herzog, Rav Reuven Katz of Petach Tikva, and Rav Zelig Diskin of Pardes Chana.

Just before the chuppah, these rabbanim appointed him as the rav and av beis din of Tzfas and the Galilee. Along with the post came the task of lighting the Lag B’omer fire. And despite his litvish background and affiliation with Yeshivas Mir, Rav Simcha seemed to don a chassidish mantle when Lag B’omer came.

“An hour and a half before shkiah, the rabbanim of Tzfas would come to my father’s house,” Rav Mordechai Dov remembers. “He would receive them with great excitement, and would serve them lekach and whiskey in honor of the yahrtzeit. After making l’chayim, the group would travel in two taxis to Meron. There were seven seats in each taxi. The whole way, they’d sing ‘Bar Yochai’ and ‘Amar Rabi Akiva.’

“We’d arrive in Meron as the sun began to set. There was a police station across from the gas station; that’s where we’d get out of the taxis. The police had these open jeeps — with chains in place of doors — and they’d bring my father up to the roof in one of those jeeps. The mountain was covered with tents, peddlers, and market stalls. A few chassidim would be waiting for my father at the top, but the crowd that I remember back in those days was mostly traditional and Mizrachi.

“Right when they arrived,” Rav Kaplan continues, “they would daven Maariv. My father was very particular, in keeping with family tradition, to begin davening Maariv 20 minutes after shkiah. He was strict about this even when Lag B’omer fell on Motzaei Shabbos, like it does this year — despite the fact that the Religious Affairs Ministry used to advertise that the main fire would take place midday on Sunday to prevent chillul Shabbos.

“The long-standing tradition was to light as early as possible at the beginning of the evening. In such years, my father would quickly make Havdalah as soon as there were three stars in the sky so that he could travel right away to Meron. For him, it was a mission, and he couldn’t take any risks that would alter tradition.

“After Sefiras Ha’omer, my father would take a lit torch in hand, bringing it to a central pillar that had been wrapped with cotton and rags and even expensive clothes that were saturated with oil — all in honor of the Tanna.

“As the fire took hold, my father’s eyes would fill with tears, and he would sob. I still remember the words he’d say: ‘What an amazing thing is happening, a tremendous miracle. Tens of thousands of people come here, just ten kilometers from Lebanon, and there are no missiles or mortars.’”

Near and Far

Back when Rabbi Kaplan was a child, there was no band. “Not even a clarinet!” he says. “The only music was the voices of people singing the special piyutim of Lag B’omer. Some 40,000 to 50,000 people would come to the site throughout the day. In later years, the number grew to 100,000. Today, police estimate that half a million people visit the tziyun on Lag B’omer.”

Along with the growth in numbers, the atmosphere at the site has also become more elevated. “Back then, there was no gender separation in the courtyard of the tziyun. Often, one would see scenes that did not suit the holiness of the site — to put it mildly. Not all the dancing was of the type that was suitable, especially at night.

“Until 25 years ago, even the tziyun itself had no mechitzah. When they wanted to put one up, there were elements that opposed it, claiming that it would offend the honor of the earlier generations.

“In response, the rav of Meron, Rav Meir Stern, said, ‘If the dress in our days would be the way it was in the days of our mothers, then perhaps it would not be necessary to have a mechitzah. But today, when unfortunately the tzniyus situation is so bad, we cannot think otherwise.’ Indeed, the tziyun on Lag B’omer today has a much more modest atmosphere than in earlier years.”

But Rav Kaplan feels that there was something very unifying about the atmosphere then: everyone would stream to the tziyun, regardless of their affiliation. He still remembers the words his father would say as he lit the fire and surveyed the crowds of people — all those seekers — who had made the trip to Meron: “Near and far, great and small, religious or not, all are drawn to Rashbi. Even if a person is very far from his heritage, he won’t leave Meron before pouring out his heart. There is a secret here that cannot be grasped by the human mind.” Then, as tears began to choke him, Rav Simcha would say, “Rashbi is the magnet of Klal Yisrael!” — and finally succumb to his emotions, crying like a little boy.

Passing the Torch

For 39 years, from 1948 to 1989, Rav Simcha had the privilege of fulfilling the family mission. There were only two years that he didn’t do it: 5709/1949 and 5720/1960, when Rav Mordechai Shlomo of Boyan ztz”l, who lived in New York, visited Eretz Yisrael. Those years, the Rebbe carried out the dynasty’s tradition and lit the fire.

In 5745/1985, Boyaner chassidus crowned the current Rebbe shlita as their leader. Unlike his predecessors, the Rebbe made his home in Eretz Yisrael, and as such Rav Simchah Kaplan wanted to give the privilege back to the scion of the dynasty. But the Rebbe, due to his modesty and a sense of hakaras hatov to the rabbinic family that had held the tradition for so long, refused to take the honor from Rav Kaplan. Instead, he asked the venerated rav to light the fire together with him. This continued for five years, until Rav Kaplan passed away in 1989 and the Boyaner Rebbe continued the tradition alone.

Boyaner chassidus carefully guards this privilege and sees this moment as one of the pinnacles of the year, with thousands of Boyaner chassidim in attendance to watch the Rebbe light the fire. But it is far from the only fire dotting the mountaintop. Today, the number of visitors has swelled way beyond the imaginations of that original band of anshei Meron. The mountain is filled with a never-ending stream of people, all seeking the promise of Rabi Shimon bar Yochai. Music and prayer fuse as countless fires fill the skyline.

Rabbi Kaplan has mixed feelings about the fires and what they represent. “The beauty of Meron is that it connects everyone,” he muses. “Today we have many fires. The crowd has grown, the chassidic world has grown, and Boyan itself is hundreds of families, thousands of people. So it was inevitable.

“But all those who call the central hadlakah the ‘Boyaner fire’ are getting it wrong. The Rebbe always emphasizes that it is Klal Yisrael’s hadlakah. The tradition of lighting it may belong to the Boyaner Rebbes. But it’s Am Yisrael’s fire.”

(Originally featured in Magazine, Issue 509)

Oops! We could not locate your form.

Comments (0)