The Angel of Curacao

How Dutch consul Jan Zwartendijk saved thousands of Jews

Photos: Boys Town Jerusalem and Zwartendijk Family Archive

When Jan Zwartendijk heard the telephone ring in his office, he hesitated. It was almost six o’clock in the evening. He was already outside, ready to go home to his wife Erna and their three children. The treelined Laisves Aleja, Kovno’s widest boulevard, beckoned.

The telephone was still ringing.

He knew it couldn’t be a customer. Not on that day: May 29, 1940. Everyone in Kovno, then Lithuania’s capital, was too busy. They were either anxiously awaiting the arrival of the dreaded Soviet army or savoring the last few hours of Lithuania’s freedom.

Nor could it be his boss at Philips’s headquarters back in the Netherlands. International phone calls were too expensive even for one of the world’s largest manufacturers of radios and other electrical equipment.

The telephone was still ringing. Who was calling?

Zwartendijk reentered his office — and at that moment, the 43-year-old businessman from Holland entered Jewish history. For in just a few short months, “Mr. Radio Philips,” as Zwartendijk was known in Kovno, would be the catalyst for saving more than 2,000 Jewish lives, including the entire Mir Yeshivah, and receive a new moniker: the Angel of Curaçao.

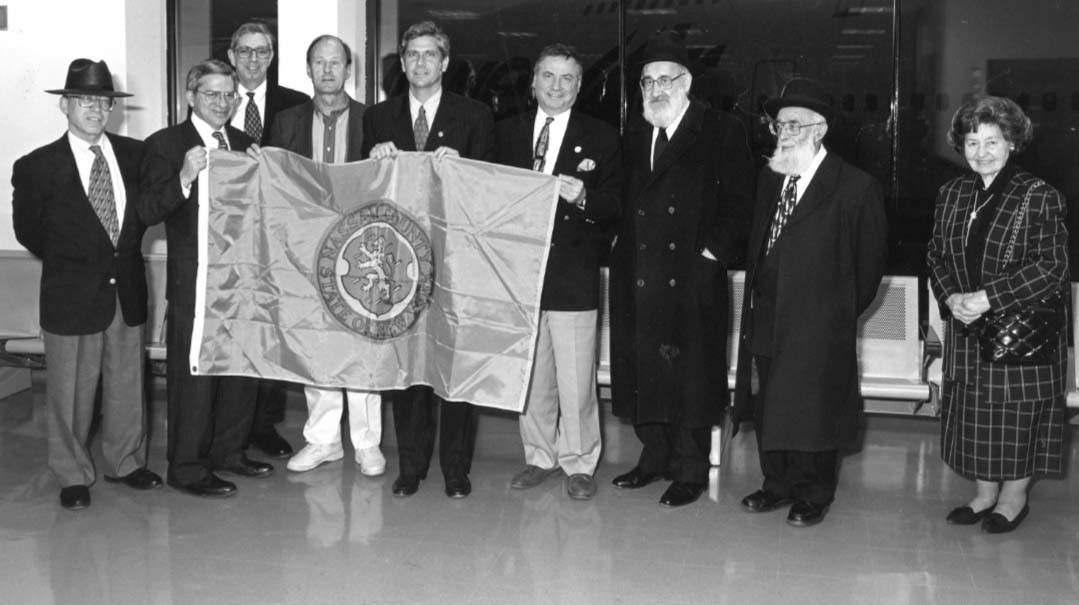

Jan Zwartenkijk never knew if the thousands of Curacao visas he issued actually helped anyone survive, but his children learned the answer: Their father had saved over 2,000 Jews. Jan Zwartendijk Jr. enroute to Israel from New York with a grateful group of survivors

Calling Mr. Radio Philips

In September 1939, the Germans overran western Poland, while the Soviets occupied the eastern half. More than 10,000 Polish Jewish refugees fled to Lithuania, which at the time was a neutral country. (It would be occupied by the Soviets in June 1940 and then by the Germans a year later.) Among the refugees from Poland were thousands of rabbanim and yeshivah bochurim.

The Germans also invaded their neighbor to the west, the Netherlands, and occupied that country in May 1940. But Dutch queen Wilhelmina and the government didn’t resign; they went into exile in England. From there they still ruled over their territories in the East Indies, as well as in the Caribbean: Suriname, a small country on the northeastern coast of South America, and several islands in the West Indies, including Curaçao. And they still had envoys and consulates in many countries.

Ambassador L. P. J. de Decker was one of those envoys. Stationed in Riga, Latvia, his territory also included Estonia and Lithuania. It was the latter country that was giving him a headache. The Dutch consul stationed in Kovno, Herbert Tillmanns, whose wife was a suspected Nazi sympathizer, had resigned rather than be fired. De Decker needed to find a temporary replacement. He picked up the phone and dialed the number of the Philips manager in Kovno.

When he heard de Decker’s request, Jan Zwartendijk protested that he was a businessman, not a diplomat. That was fine, de Decker assured him. Envoys were diplomats. Consuls, who were on a lower rung in the diplomatic hierarchy, just had to renew a few passports and help Dutch citizens in other small ways.

Zwartendijk correctly guessed that in wartime, even a consul would have more serious, and possibly dangerous, work to do. But when he continued to protest, de Decker played his trump card: The Netherlands needed a loyal representative in Lithuania. Those who opposed Nazism and Communism couldn’t hide their heads in the sand and do nothing. Besides, de Decker assured Zwartendijk, he would give the new consul any help he needed.

Jan Zwartendijk accepted the job. He also agreed to house the consulate, which didn’t have a permanent home, in his office. He had to get permission from Philips for both, but he and de Decker knew that wouldn’t be a problem.

Until 1939, the CEO of the company was Anton Philips, who was descended from Jews who left Germany in the mid-1800s. Worried not only about the possibility of war, but also Germany’s virulent anti-Jewish sentiment, Anton Philips began transferring the company’s Jewish senior managers to safety in the Americas in the early 1930s. He also tried to keep the company free from Nazi sympathizers. Anton’s successor, Frits J. Philips, would continue to try to protect his Jewish employees even after the Germans occupied Holland. And when the Nazis tried to force the company to help with the German war effort, Frits Philips — who would later be named one of the Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem — did what he could to sabotage production.

Although Zwartendijk’s official appointment would only come a few weeks later, he unofficially became the new Dutch consul that evening. After he picked up the consular stamps and some official documents from Tillmanns, he was in business.

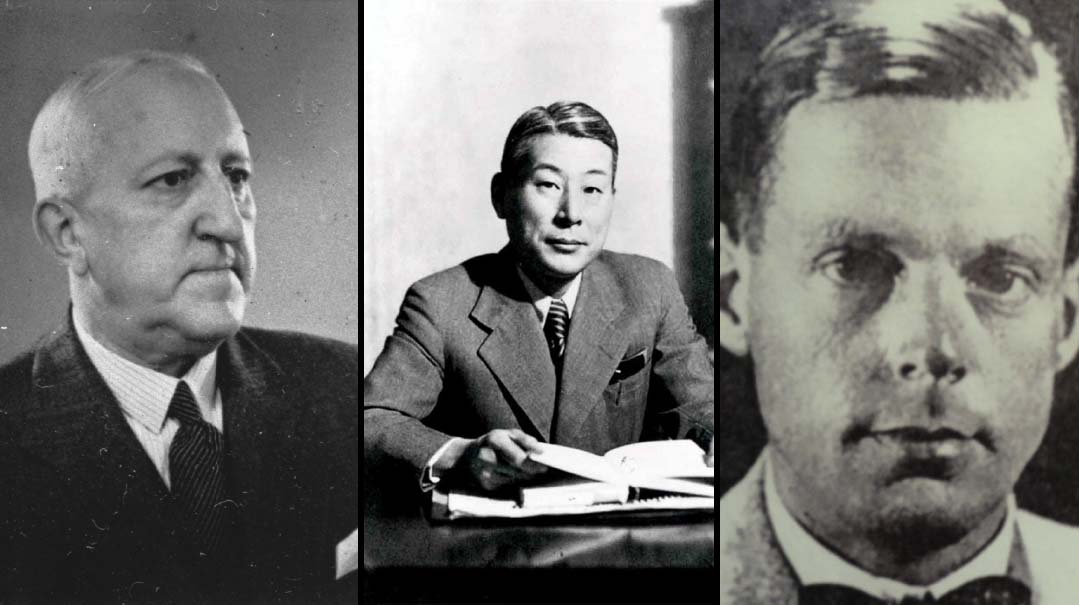

Dutch ambassador L.P.J de Decker, Jan Zwartendijk, and Japanese consul Chiune Sugihara. With a destination visa to Curacao and a transit visa to Japan, there was hope

Next Ones to Go

De Decker called Zwartendijk again on June 13. By then the Soviets had occupied Vilna. They hadn’t yet reached Kovno.

“Everyone’s holding their breath,” Zwartendijk told de Decker. “It’s like watching at a deathbed.”

On the evening of June 15, the wait came to an end. Hundreds of Soviet tanks drove into Kovno. They encountered zero opposition.

The Soviets immediately began to round up Kovno’s intellectual elite and Lithuanian nationalists. Some were banished to a Soviet gulag, including Zwartendijk’s landlord. Others were hanged from trees.

Zwartendijk responded to the general fear and chaos by going to work every day. Even though there was nothing to do at the factory, which would soon be nationalized by the Soviets, he could keep open the consulate.

His first job as a wartime consul was soon in coming. A Dutch priest living in Kovno had dared to protest the many arrests in his parish. Now he had disappeared. After consulting with de Decker, Zwartendijk met with a Soviet army officer, who told him not to bother about the priest — the Soviets planned to close all religious institutions. Consulates were next. The meeting was over.

His first failure as a consul weighed heavily on Zwartendijk, who resolved to do more in the future. He got his chance when a Jewish woman named Pessla “Peppy” Lewin walked into the consulate.

Refugees, having been issued visas by Zwartendijk, wait outside Japanese consulate. Sugihara could barely keep up with Zwartendijk’s pace

Nowhere to Go

When war broke out in 1939, Mrs. Lewin and her family — her husband, Rabbi Dr. Isaac Lewin, and their three-year-old son, Nathan (who would grow up to become a famous Washington attorney) — were living in Lodz, Poland. Visiting from Amsterdam were Mrs. Lewin’s mother and brother. Like many others, they all immediately fled to nearby Lithuania. But Mrs. Lewin sensed that Lithuania was only a temporary haven. A Dutch citizen before her marriage to her Polish husband, she sought out the Dutch consul in Kovno; she wanted to know if her entire family could travel to Java, in the Dutch East Indies.

After consulting with de Decker, Zwartendijk regretfully informed her that only Dutch citizens, such as her mother and brother, could enter the Dutch colony. Unwilling to take no for an answer, Mrs. Lewin wrote to de Decker directly — and received the same answer.

She wrote to de Decker again, asking if there wasn’t any Dutch colony where she and her husband and child would also be welcome. This time de Decker had a suggestion. Curaçao, in the West Indies, didn’t require a visa. But she did need to get permission to land from the island’s governor.

Unfortunately, the governor wasn’t letting most people land. The island housed oil refineries, which provided fuel to the Allied forces. The governor wasn’t taking any chances that an enemy agent might enter along with bona fide refugees.

In her next letter, Mrs. Lewin asked: And what if her family didn’t actually want to land in Curaçao? What if they intended to settle in America or Australia? Could Ambassador de Decker write just the part about Curaçao not needing a visa — and leave out the bit about needing the governor’s permission?

“Send me your passport,” wrote de Decker, who had witnessed the Nazis’ treatment of Jews during his previous posting in Dusseldorf.

When she got back her passport, she returned to Zwartendijk and asked him to do the same for the rest of her family. Zwartendijk agreed.

Mrs. Lewin still had a problem. The family had to go somewhere. With Germany cutting off refugees from the rest of Europe, the only way out led eastward, across Russia via the Trans-Siberian Railway. From the port city of Vladivostok, refugees could board a boat to Japan, if they had an exit visa from the Soviets and a transit visit issued by the Japanese consul. Even if they got the exit visa — at this point the Soviets were happy to let the refugees leave — the Japanese transit visa allowed them to stay in Japan for only ten days. What if no country would allow them to stay permanently? Would the Japanese send them back to Russia?

Today we know most of the refugees were allowed to remain in Shanghai until the end of the war. The Lewins didn’t. But despite the dangers, they decided to risk the long journey. On July 26, Mrs. Lewin went to the Japanese consulate — with yet another worry. Would the Japanese consul, Chiune Sugihara, honor the bogus Curaçao visa?

Ten Days of Visas

At this point, readers familiar with the more widely publicized Chiune Sugihara story may be scratching their heads. Wasn’t it Nathan Gutwirth, a 23-year-old bochur learning at the Telshe Yeshivah, who was the first to get the precious visas?

There is a saying: Great minds think alike. They also think quickly. While Mrs. Lewin was planning her family’s escape route, Gutwirth was doing the same for himself and his fiancée Nechama. His first choice was the United States, but Nechama had a cousin who lived in Curaçao. That would also do.

Gutwirth, a Dutch citizen, knew Zwartendijk personally, thanks to their mutual interest in Dutch football. But despite his protektzia, Gutwirth also had to first receive permission from de Decker to get his visa for Curaçao.

After receiving his visa, Gutwirth told the story to Zerach Warhaftig, a Polish refugee who had been a leader of the Mizrachi movement in Warsaw, and who would later become Israel’s longtime Minister of Religious Affairs. They discussed the perilous situation of the hundreds of yeshivah bochurim trapped in Lithuania. Would the Dutch consul be willing to issue hundreds of these bogus visas — and would the Japanese consul be willing to issue the necessary transit visas?

There was only one way to find out. Gutwirth returned to Zwartendijk, who by then had received permission to write the visas without first going through de Decker. Zwartendijk took just a few minutes to consider, before giving his answer: de Decker hadn’t set a limit to the visas issued. He wouldn’t either. Whoever wanted a Curaçao visa could get one.

As for Sugihara, he had already decided to disobey Tokyo’s instructions to limit transit visas. He also issued his visa to whoever wanted it, whether the person’s end visa was valid or not. (So, yes, the Lewins got their transit visa.)

The next day, dozens of Jewish refugees were waiting outside Zwartendijk’s door. A few days later, there were hundreds. As word spread, there were thousands.

When Zwartendijk and de Decker had first discussed the idea of the Curaçao visa, de Decker thought it would be for just a few Dutch citizens stuck in Lithuania. Zwartendijk decided not to tell de Decker about the visas he was issuing to Polish refugees. What the career diplomat didn’t know wouldn’t hurt him.

With the Russians, Zwartendijk used a different dodge. When a Russian officer threatened to close the consulate because the crowds were supposedly causing a hazard to public safety, Zwartendijk bribed him with a new-on-the-market Philips electric razor, giving new meaning to the words “a close shave.”

“My father did what his conscience told him he had to do,” daughter Edith Jes-Zwartendijk would later tell Jan Brokken, author of a book about Zwartendijk and the Curaçao visa, The Just: How Six Unlikely Heroes Saved Thousands of Jews from the Holocaust.

Her younger brother, Jan Jr., added that their father had a personal code: “Make sure you’ll never have to feel ashamed of using your family name.”

Zwartendijk handed out visas for ten frantic days. At first, he wrote each visa by hand. Then, to save time, he ordered a stamp with the French text; only his signature was handwritten. His office hours were 7 a.m. until 6 p.m. When there was still a long line waiting outside his door, he would stay later.

Sugihara, who had to write the Japanese text of his visas by hand, often called Zwartendijk and begged him to slow down. He didn’t. As he had suspected, in early August, the Soviets nationalized all companies with more than 20 employees, which included Philips. Zwartendijk was forced to shut down the consulate on August 3, but before he closed the door, he had issued an astounding 2,139 visas.

They Would Have Shot Us

A few days later, Zwartendijk drove back to his former office. After checking there were no Soviet soldiers milling around, Zwartendijk entered the building via a back door. With the help of two loyal assistants, he burned everything having to do with the consulate’s activities, including the stamp for the Curaçao visa and the list he had kept of the names of those who received visas. He had no idea if the refugees would make it out of Russia — in fact, he thought they had only a slim chance of succeeding. He was therefore afraid the list might put their lives in danger.

He also feared for his own family’s safety. When the Zwartendijks left Kovno, they returned to Nazi-occupied Holland.

“There were Nazi officers living next door to us,” Robert Zwartendijk, the youngest of the three children, told Mishpacha. “If they had learned that my father helped thousands of Jewish refugees escape, the Nazis would have shot my father and the rest of us.”

Zwartendijk and his family didn’t leave Kovno until early September. In one of history’s ironies, the man who had helped so many get visas had trouble getting a Soviet exit visa for himself. But apparently he used the extra month of waiting in Kovno well.

When author Jan Brokken searched through Lithuanian National Archives doing research for his book, among other things he discovered in the files was a Curaçao visa signed by Zwartendijk on August 23, a few weeks after the consulate closed. Apparently Zwartendijk had made a secret second set of official stamps and was still issuing visas. While we don’t know how many more visas Zwartendijk issued, Brokken estimates there were at least a few hundred more.

Who Survived?

When Zwartendijk retired from Philips in 1956, he and his wife moved to Rotterdam, where Zwartendijk had grown up. They looked forward to a peaceful life. Then in 1963 the telephone rang. At the other end was a woman from the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

“Are you the Angel of Curaçao?” she asked.

It was a surprising question. For two decades, Zwartendijk hadn’t heard a word about the people who received his visas. Did this mean some of them survived the war?

The phone call was due to an article in the B’nai Brith Messenger of Los Angeles, in which a survivor claimed the mysterious Angel of Curacao had been the Dutch consul in Kovno. Now the Foreign Ministry was requesting clarification about the assistance Zwartendijk had offered during his time as consul.

Zwartendijk, sensing that trouble was brewing, downplayed what he had done, reporting that he had granted only about 1,200 to 1,400 visas. Even that turned out to be too many. In February 1964 he was summoned to the Foreign Ministry’s offices, where he was reprimanded for breaking the rules.

The reprimand transformed Zwartendijk from a usually cheerful man into a morose soul. The only balm would be to discover what happened to “his” Jews. A few letters from survivors had trickled in, after the newspaper article. But did anyone else survive? Or had Zwartendijk sent the others to their doom? That latter possibility gave him no rest.

During the next decade, sons Jan Jr. and Robert tried to find more information. They contacted Simon Wiesenthal’s Jewish Documentation Centre in Vienna. Although Wiesenthal wanted to help, he thought this project was better suited for a new research center he hoped to open in Los Angeles in a few years.

But for Zwartendijk, time had run out. On September 14, 1976, he passed away. A few days later, as his coffin was being carried out of the house, a letter arrived from the Centre. According to research they had received, 95 percent of the Jewish refugees with visas issued by Zwartendijk in Kovno survived the war. Among those rescued were 79 rabbis and 341 yeshivah students, including the entire Mir Yeshivah.

Hidden Hero

The family would eventually learn that Zwartendijk and Sugihara had enabled at least 6,000 people to escape, as an entire family often traveled on one visa. Jan Brokken estimates the number might be even higher — as many as 10,000. But whether the number was 6,000 or 10,000 or even more, it remains one of the war’s largest successful rescue operations.

By this time, the Chiune Sugihara story was beginning to become widely known — and this put the Zwartendijk children in a quandary. They knew their father never wanted to be in the limelight, but without the Curaçao visa, Sugihara wouldn’t have written his transit visas. When Sugihara was recognized as one of the Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem in 1985, the Zwartendijks wondered: Shouldn’t our father’s work be recognized too?

A few Holocaust scholars tried to rectify the situation by including a mention of Zwartendijk in their scholarly works, including Ernest Heppner and David Kranzler. Kranzler had spoken briefly with Jan Zwartendijk in 1976, and he promised that the former Dutch consul’s actions wouldn’t be forgotten.

Kranzler got a chance to make good on his promise to make Zwartendijk’s story more widely known several years later, when he was at a bris that was also attended by Rabbi Ronald L. Gray, executive vice president of Boys Town Jerusalem.

Boys Town Jerusalem was founded in 1948 as a response to the murder of 1.5 million children during the Holocaust. Its goal is to give Israeli boys from disadvantaged backgrounds a solid Torah and technological education that will enable them to build a better life for themselves, inspired by traditional Jewish ideals. But even the most idealist institution needs money, and Rabbi Gray was searching for an appropriate person to honor at their annual fundraising dinner.

“Dr. Kranzler and I started schmoozing,” Rabbi Gray recalls, “and I asked if maybe he knew someone. He said, ‘Yes, I do. Jan Zwartendijk.’ Everyone had heard of Sugihara, but Zwartendijk was an unsung hero.”

Rabbi Gray arranged for Edith, Jan Jr., and Robert to attend a ceremony at Boys Town Jerusalem’s campus in Bayit Vegan in the spring of 1996, where a memorial to Jan Zwartendijk was unveiled. The siblings also attended the dinner held in New York in the fall. The events were covered by several New York publications, including the Jerusalem Post, which penned the headline: “The Man Who Saved Judaism.”

“Rabbi Gray was the first to pick up the story and make it public,” says Robert Zwartendijk.

Yet as important as it was to the family to set the historical record straight, the dinner was memorable for another reason.

“Many survivors attended,” Robert recalls. “After the dinner, they said, ‘We want to show you something.’ They showed me their passports with the visa and my father’s handwriting. It was very emotional for me.”

Rabbi Gray and Dr. Kranzler were also instrumental in having Yad Vashem recognize Jan Zwartendijk as one of the Righteous Among the Nations in 1998 — yet another emotional moment for the Zwartendijk children.

After the 2018 publication of Brokken’s book The Just, which has been translated into several languages, other public recognitions have followed, including a memorial in front of the Kovno building where Zwartendijk issued his visas and an exhibit at the Philips Museum in Holland. And a painful memory was healed when the family received an official public apology from the Dutch foreign ministry for that earlier reprimand.

“My father would have hated all this,” Robert Zwartendijk admits. “He was a modest man. We, as his children, wondered if we should allow this publicity to happen. But then we remembered words our father told us: In life you will be faced with choices. You can make the easy choice, or the right choice.

“In Lithuania, the easy choice would have been to say to the refugees, ‘I can’t help you. I can’t do anything that isn’t according to protocol.’ No one would have reproached my father for doing that. But he said, ‘If I can save lives, I should do it.’

“If someone could learn from his example, we think he would have agreed to let us publicize his story.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 901)

Oops! We could not locate your form.