The Amazing Adventures of a Globe-Trotting, Treif-Spotting Kashrus Supervisor: Part II

| February 24, 2021Another glimpse at how certified products get to your table from the corners of the world

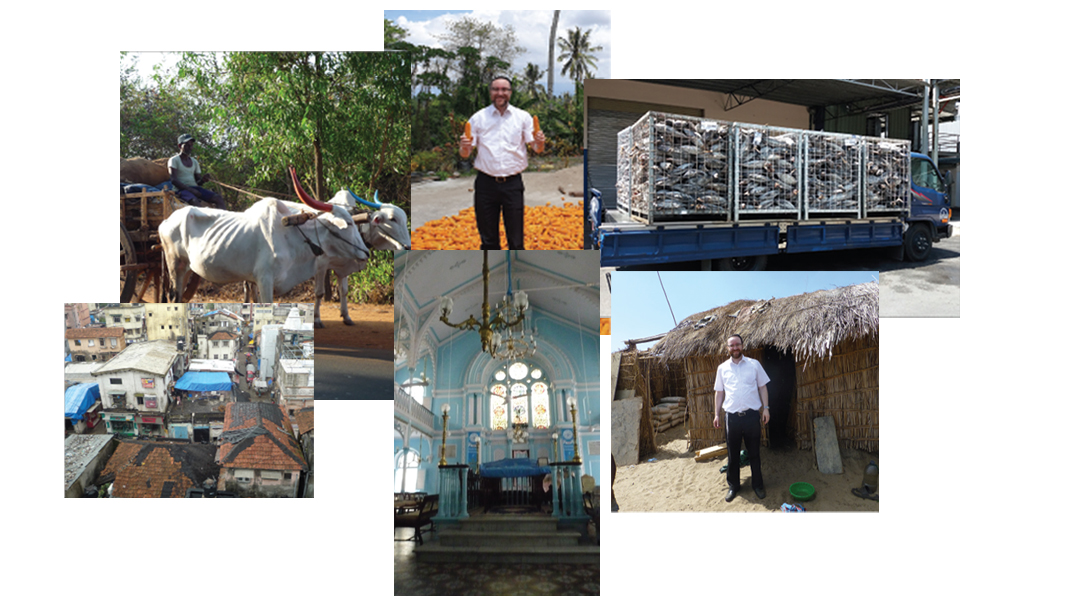

Photos: Rabbi Danny Moore

Meticulous attention to detail, a cool head, and high tolerance for long, uncomfortable journeys are all part of Rabbi Danny Moore’s work in international kashrus. From his very first job supervising an early-morning milking as a favor to a friend, Rabbi Moore was drawn into a world where one sharp glance — and a dose of Heavenly help — is the difference between kosher and treif. More than two decades and 51 countries later, he’s the kashrus director of Badatz Igud Harabbonim, the Manchester-based hechsher famously led by Dayan Osher Yaakov Westheim ztz”l, who was niftar earlier this year. The hechsher now continues under the supervision of the Dayan’s son-in-law, Rav Shulem Landau.

Last year, Mishpacha presented some of Rabbi Moore’s more interesting kashrus adventures, but after 22 years in the field, the stories don’t stop.

Stewing in Their Own Juice

Where: Kayseri, Turkey

I was once asked by two different mehadrin hechsherim, one based in the UK and one in the US, to represent them in supervising a production of orange and apple juices in Turkey.

The fruit juice factory, owned by a big Turkish entrepreneur, was situated next to the main mountain road that runs from the city of Kayseri to the city of Adana in the South. I flew from Manchester to Istanbul and then took an hour-and-a-half domestic flight to Kayseri airport, where I was met and driven to the plant. When I got there, I saw that the owner had built a gas station with his own gas pumps, a restaurant and service area, and a guest house right next to his factory. This attracted a lot of the truck drivers who stopped for a break on their way down to Adana.

He was obviously a capitalist and a shrewd businessman.

Like all mashgichim and visitors to his factory, I was put up in the guest house. In order to get to my room, I had to walk through the restaurant, and I noticed that the fridge of cold drinks there carried no Coke, Pepsi, or Schweppes — only the company’s own fruit juices.

Of course, I had done plenty research before I came. When you kasher a factory, you have to know exactly what you are koshering it from. Has it been used for dairy? For treif products? Or is it only used for non-problematic foods, in which case you are basically koshering “l’chumrah”?

There is a certain piece of filtration equipment that is extremely delicate and difficult to kasher, and our main concern was grape juice. In all our discussions with this company, they had told us that while they made apple, orange, apricot, and pomegranate juices, they haven’t produced grape juice for the last 20 years. And in fact, our online checks didn’t turn up any grape juices under their label. They did tell us that they had done a recent run of a kosher grape juice for a certain hechsher, but other than that, no grapes came into the factory.

The production began and all was going well.

A few days later, one of the managers asked me if I would be able to help them out by sending a sample of the recently produced kosher grape juice to the hechsher in question.

I explained that I would like to help them, but couldn’t, because I was not authorized to open the seals on that kosher product unless asked to do so by their rabbi.

Soon enough, I got a call from the rabbinical authority on that hechsher asking me to supervise the sample-taking of their product. And so, we went to the 50,000-liter tank of kosher grape juice, I unsealed the tape, took off a small sample, closed it and sealed it again. Then I was shown into the laboratory to pasteurize the grape juice and pour it into small sample bottles. I was required to do this for them, to prevent a problem of “stam yeinam,” which would make the grape juice forbidden.

I was about to close the sample bottles, when the non-Jew said to me, “Can I just add something?”

He was holding a small bottle of grape flavor.

I said, “You can’t add that, it’s not kosher. And, if you do, the end product won’t match this sample.”

He said, “Don’t worry about that, rabbi.”

I told him that I would only seal it as it is, and I would not add anything. Okay, it got sent off as it was. But I realized that I was dealing with cheaters.

My antennae were up. I looked all over the factory for evidence of grape juice production, which would mean that the machinery was used for “stam yeinam.” But I couldn’t find anything, and I had to be very careful lest they realize I was suspicious. I spoke to the fellows lower down on the line, the factory workers, but I wasn’t able to ferret out any information.

The industrial boiler in this factory ran on coal. During the winter, they sometimes had stoppages due to the coal getting wet, and that happened one day while I was there. The manager let me know that we would have to wait a couple of hours, as production would be halted while the boiler was cleaned out.

Most of the staff went home, and it seemed like a good opportunity to poke around. I decided to check out the warehouse to see the pallets that had been prepared for shipment. The warehouse was a huge underground storage area, the size of the entire factory. Security was fairly tight, few people were allowed in, but my excuse was that I wanted to see how many pallets of juice we had already produced. I asked Mehmed, the production manager, he agreed to get the key from someone, and we went down the steps and through a heavy metal door.

He showed me our product. I counted them, checked them, sealed them, and marked them, then I started walking through the other dozens of aisles.

“Do you need to see something?” he asked me.

“No, I’m just looking around.”

“Okay.”

Then, a minute later, Mehmed said he needed to go upstairs for something.

Even better, I thought. But two minutes after the production manager left me, the lights throughout the warehouse suddenly went off. It was pitch black, a cavernous underground room, and the aisles all looked the same.

I had my phone with me for a little light, and I suddenly saw a light coming from the far end of the warehouse. Walking toward it, I saw it was an office, where a guy sat alone working on his computer. He obligingly stood up to help me, leading the way to a big switchboard, but nothing happened when he flipped the switches. The mains had been switched off.

I made my way upstairs and found Mehmed, telling him that the lights had suddenly fused. He feigned total surprise. “Really?”

We walked back down the staircase, and the metal door was locked.

“Can we get the key again?” I asked.

“No, the guy who has the key has just gone home. It’s impossible to open it without him.”

“If he’s just left, maybe you can call him on his cell phone to return. It was open just minutes ago.”

“We can’t do that, no. He’ll be in tomorrow.”

By that point, I had a pretty strong feeling that they were hiding something. But I needed to catch them without confronting them.

Suddenly, the image of the fridge in the restaurant, with all the company’s juices, crossed my mind. I told Mehmed I was going over to have a rest in my room, since they anyway weren’t working. He was quite happy for me to leave him alone.

By that time, it was dark outside too. We were in quite a lonely spot in the Turkish mountains, and as I opened the door, I heard the loud barking of several wild mountain dogs. They ran at me, but I ran back to the factory and managed to close the door on them. I don’t love dogs at the best of times, but these wild creatures were something fearsome.

I found Mehmed again and told him there was a pack of wild dogs just outside the door. He came out with a big stick and beat away the huge dog that was sitting at the door. It scarpered. I would have preferred him to accompany me the whole way across the yard, but he left me with an assurance that “you’ll be okay, they won’t touch you now.”

I ran across the yard, through the service area with the gas pumps, and arrived out of breath at the restaurant.

“Ah, good evening, Rabbi, help yourself to a drink.” The Turk manning the restaurant was always very friendly, constantly offering to heat my double-wrapped meals or serve me drinks. I greeted him and went across to the fridge. I scanned the shelves, peach and apricot and orange, and there, unmistakably, was a small box of grape juice. I took it and slipped it into my pocket, without him noticing, and then I took an apricot juice and showed it to him with a big smile and a wave.

I went back to my room, shaking. These people had been lying to us for months. I took a few photos of the little box drink and called the rabbanim of both hechsherim right away. But I could not let the Turks suspect anything. I made sure to tell them I was very happy with the production. After all, I needed them to drive me a couple hundred miles to the nearest airport, and I would not have put it past them to leave me on the side of the road, or induce customs officials to detain me.

I went straight from the airport to the rav’s house and showed him the grape juice box. He was so shocked that he dropped it on the floor. Then I emailed the Turkish export manager with whom I had dealt one more time.

“Do you make any grape juice under your label at this plant or any other?”

“No grape juice, no. We don’t make such a thing.”

The Amazing Adventures of a Globe-Trotting, Treif-Spotting Kashrus Supervisor

Fit for the Gods

Where: Bangkok, Thailand

I was on a trip to Thailand for kosher production of everyone’s favorite canned fish, skipjack tuna. The job was to supervise a huge cannery in Bangkok, a massive operation with a workforce of thousands.

Skipjack tuna is caught by fishing vessels in the Maluku Sea. The method used by these boats, called purse seiners, is to hang a vast fishing net vertically in the sea. Once an entire school of tuna is located, they encircle it with the net, and then pull in a line that purses the net closed on the bottom, so the fish can’t escape downward. The massive raw tunas are immediately frozen, then they’re sawed apart, gutted, and precooked in big steam ovens. After that, there are huge teams of ladies and girls in the factory who remove all the skin and bones, and place the good parts of the fish into trays ready for canning.

This vast factory is active around the clock. Because fish has the same halachah as meat, that it always has to be within sight of the mashgiach (it cannot be “misaleim min ha’ayin — hidden from sight”), we use a team of two mashgichim working in shifts. I’d work for ten or twelve hours, then go for a rest while my partner took over.

The job involves switching on the ovens for bishul Yisrael, and checking every single fish for scales (if it has scales, it automatically also has fins). As the frozen fish come into the factory, we know how to position the fish so each one can be checked for scales after it defrosts, before being precooked.

The factory provides mashgichim with a little air-conditioned office, table, and chair, which we can use for davening, eating, or making phone calls during our stay. As hosts, they also like to provide us with refreshments, although they know that we can’t eat anything. On the first day that I was working in this specific cannery, the director of marketing came in to make sure I was comfortable with the office provided, and she brought some refreshments.

Just to give some background, Thailand is a Buddhist country. On almost every street corner in Bangkok, you’ll see temples filled with idols and images. Buddhist monks in orange minimalist robes are all over the street. Every taxi has a little Buddha hanging, which I ask the driver to remove for the duration of my trip. Even in the workplace, every management office has their own plug-in electric Buddha. It sits there, lit up in the corner, and there are little cups of wine and oil which are poured before it — a real live example of avodah zarah and yayin nesech — as well as burning sticks of incense. I would politely explain that I was very sensitive to smells and ask them to switch off the Buddha and not burn the incense when I was in the room.

So here I was in this little office, and the export manager brought in a beautiful tray of exotic fruits. She explained that they were aware I couldn’t eat any non-kosher processed food, but fresh fruit was surely all right.

I asked if it was local fruit or possibly imported from Israel, and she said it was locally grown. I looked at the tempting tray again. It seemed very high-quality, better than what I had seen sold around the city, so I asked, “Where did you get such nice fruits?”

“Oh, these are top quality. They were eaten by our Buddha.”

Alarm bells were going off in my mind as she continued to explain.

“When you drove in to our plant, I am sure you noticed that we have a temple for our workers’ use in the corner of the yard. We serve choice fruits and libations to be eaten by the Buddhas. Well, they don’t actually eat it, but we call it eaten… and the next day we remove it. So I thought I would give some of this holy fruit to the holy people.”

I said, “That’s very kind of you, I’m truly honored. But I actually can’t eat the fruit if it has been served in the temple.”

“Rabbi, I think you’re making a mistake. Last month we did another kosher production, and the rabbis ate this fruit every day of their stay.”

“Well, uh, did you tell them where it came from?”

“Oh, no. They didn’t ask.”

I followed it up and got the details of the mashigichim of that kashrus agency. They were pretty upset, but thanked me profusely for the information, because they had another booking to go back and produce more skipjack tuna from Bangkok for the kosher public.

Time and Place

Where: Mumbai, India

It was around a year after the tragic murder of the Holtzbergs in Mumbai, that I found myself stuck in the city for Shabbos during the ash cloud crisis. I spent Shabbos at the Chabad house, Nariman House, which was temporarily housed in an apartment, after terrorists had trashed their building. There was no permanent replacement shaliach yet, so it was manned by two bochurim. On Motzaei Shabbos, as we were seated at Melaveh Malkah, we began to go around the table telling stories.

At the table there was an elderly Jew of Bene Yisrael origin named Bentzion, who served as the gabbai in the Iraqi shul in Mumbai, Knesset Eliyahoo — and this was his unforgettable story:

“One winter evening last year, I was invited by Gabi and Rivka Holtzberg for supper. Supper was at eight o’clock, and Maariv at the Chabad House was called for nine o’clock. We had a lovely meal, and when it was over, we waited for a minyan. I knew it could take a while, because we were waiting for the frum businessmen and diamond traders to come in. Nine o’clock came and went, so did 9:10 and 9:15, but no minyan appeared. At 9:20, in walked two mashgichim.

“They were Rabbi Aryeh Leibish Teitelbaum, son of the Volover Rav and son-in-law of the Toldos Avraham Yitzchak Rebbe, and his assistant, Rabbi Benzion Kruman. Rabbi Teitelbaum lived in Meah Shearim and traveled a couple of times a year on behalf of the Volover Rav’s hechsher, and Rabbi Kruman lived in Bat Yam. His main job was administrator of the Sadigura mosdos in Bnei Brak, but he used to travel occasionally to help Rabbi Teitelbaum.

“They walked in, sat down, and took seforim to learn while they waited for a minyan to start. By 9:30, I decided to leave and go to the Ohel David synagogue, which is some distance away, hoping that maybe a minyan would gather there for Maariv at ten. At 9:40, two evil terrorists stormed into Nariman House and took it under siege — Gabi and Rivka were killed al kiddush Hashem, and so were Rabbi Teitelbaum and Rabbi Kruman.”

Bentzion concluded his narrative and the conversation soon recovered and moved on. To me, his words were chilling. It was an unforgettable story of Providential irony, of Hashem taking two rabbanim whose lives were lived far away, in Meah Shearim and Bat Yam, and placing them in this building on a poor market street in South Mumbai to be killed al kiddush Hashem, while Bentzion, a Mumbai native who was often in that building, left minutes before and remained alive.

There is another Chabad house in India that I’ve frequented — this one in New Delhi, which is located in a crowded marketplace called Main Bazaar. As neighborhoods go, Main Bazaar doesn’t feel that safe. It’s full of backpackers, with plenty of lost souls to be helped, and plenty of “interesting” people wandering around too. A young Chabad couple, Rabbi Shmueli and Mira Scharf, ran it with tremendous sacrifice and devotion. In 2012, they returned to Eretz Yisrael to give birth, when a Hamas rocket from Gaza landed directly on the building in Kiryat Malachi where they were staying, killing Mira instantly and leaving her three small children orphaned. You would think that Kiryat Malachi is safer for Jews than an alleyway in Main Bazaar, New Delhi, but it was another reminder that Hashem, our Protector, puts people where they’re supposed to be, as little as we understand.

Meeting Over Mangoes

Where: Malawi, southeastern Africa

Some years ago, two British students on a gap year found themselves in the Republic of Malawi, an impoverished, landlocked country in southeastern Africa. They were enjoying spectacular hiking along the banks of Lake Malawi — nicknamed Calendar Lake because it’s 365 miles long, and 52 miles wide — when they were struck by the huge quantity of mangoes which hung unharvested from laden trees.

The mangoes were delicious — and the two backpackers quickly became entrepreneurs envisioning a profitable business. If those luscious, low-hanging mangoes could be efficiently harvested, surely they could produce juice, puree, and other products, and make a profit out of the bounty of this scenic but backward place.

They set up shop, and the mangoes were picked and processed. The first hurdle was that when it came to juicing, the Malawi mangoes actually turned out not to be the best type. But the two young Brits were so invested in their dream at that point that they brought over Israeli agronomists to assist them in growing a different strain — Alphonso mangoes — which are an Indian variety, sometimes known as the “king of mangoes.” Alphonsos are disease-resistant and have a good yield.

The partners bought up land near Lake Malawi, acquiring banana plantations too. An Indian company provided them with irrigation from the lake, although they soon switched to a system provided by Israeli company Netafim, experts in drip irrigation. They told me that when they made that switch, their yield became three to four times greater. The Israelis are really world-class in agricultural systems.

Once they’d overcome the start-up obstacles and gotten their factory up and running, mango juice and puree exports began. Clients were asking questions before making their orders, and it was time for kosher certification. Although one of the partners was Jewish, his family were members of a Reform temple in London, and he knew nothing at all about kosher. Online research soon led him to Badatz Igud Harabbonim.

I researched the facility, and could hardly believe that they had a world-class company, with European technology, running out there in the sticks of Malawi. All looked good, and it was decided that I would make the initial trip — although traveling wasn’t as simple as just booking a flight. I needed to get vaccinated against yellow fever, and began taking tablets to reduce the likelihood of being affected by malaria. One out of 50 female mosquitos in Malawi carry malaria, so you sleep there with a mosquito net fully zippered around you, in addition to a DEET spray you use as deterrent.

Since we are a mehadrin hechsher, I needed to check out the entire process, meaning the plantation as well as the factory. I arrived at Kamuzu International Airport in the capital, Lilongwe, and spent the next day being driven out to the mango plantation in a four-wheel drive through beautiful, rugged wilderness, seeing village after village of mud huts. There was no running water, so villagers were gathered around hand pumps, and only ten percent of the area has electricity, so people in these parts tend to go to sleep when it gets dark.

When we reached the plantation, the owner explained that experts from the Israeli company were in the middle of setting up the irrigation system. There was another Land Rover parked there, and he indicated a guy bending down in the field, telling me, “Avraham here has already been working on it for two months, and he’ll be here another month.”

I came up to this guy from behind, and I greeted him in Hebrew. “Avraham, mah shlomcha?”

Avraham got such a shock, he almost fainted. “A Jew! I haven’t seen any in months!” he said when he found his voice. “What are you doing here?”

We started to chat. I explained to him about the supervision necessary in order to receive kosher certification, but Avraham still just couldn’t get his head around what a chareidi was doing in Malawi. We were staying at the same hotel, so he invited me for supper.

“I can’t, I only eat kosher,” I told him. “Why don’t you come eat with me? I have plenty of kosher food in my room. I pack double-wrapped Hermolis kosher meals in my suitcase, and I heat and eat them wherever I am.”

He couldn’t wrap his brain around the idea of not being able to buy food anywhere, of preparing and bringing along every meal for a week-long trip. But Avraham came to join me for a Heat ‘N Eat kosher Hermolis meal that night. During our conversation, he told me about a scary experience he’d had while working in Malawi on a previous job. He’d gotten a fever and some malaria symptoms, and was beginning to panic that he’d caught the dreaded disease. He did a test locally, which came back negative, but his doctor in Israel told him to fly back immediately and do a test there. When that was also negative, he breathed a huge sigh of relief, but the symptoms persisted for another few months. It turned out that he had a case of severe food poisoning from something he’d eaten locally.

“That could never happen to you,” Avraham told me. “Maybe I should also start eating kosher…”

“Because I Like Jews”

Where: Irlam, Manchester

One wintery day, I was on a job in a chemical factory in Irlam, a very working-class neighborhood in Manchester. We were supervising some surfactants — these are products that reduce surface tension and are part of the ingredients used in Fairy Liquid, a popular brand-name dish detergent.

In order to produce these ingredients to our standards, we had to kasher the entire factory, including a big tank with a capacity of 95,000 liters of water, plus its pipes and pumps, a process which was set to take two days. The manager called over one of the workers on the factory floor, Kevin, and introduced me. He said Kevin would look after my needs and make sure everything was as we required. I had a chat with Kevin and explained the koshering process and what he would need to do, and I could see that nothing I asked was too much for him. “I’ll do whatever you want, Rabbi.”

Eventually, I got curious about his attitude. “How come you’re so helpful, mate?” I asked him, straight out.

“I like Jewish people,” he answered.

“Why’s that?”

“Before I got this job, I was a courier for UPS. I used to deliver parcels for a depot near Manchester, and one of the areas we covered was Leicester Road, near that Jewish area. I remember a Jewish guy, Benny Leitner, who had an office there, and every time I rang his bell, rain, snow, or shine, he’d say ‘Come inside out of the cold, can I make you a tea? Will you have something to eat?’ I can’t forget that guy, and so I like Jews.”

Mr. Leitner didn’t know it, but that kindness of his years ago helped a non-Jew go out of his way for us to accomplish a difficult koshering process.

Ironed Out

Not too far from my home in Manchester are the beautiful rural villages of North Wales. Wales is famous for its beauty and beaches, but also for its natural resources such as iron, gold, and slate. In a small village named Trefriw, on the borders of Snowdonia National Park, these combine at a hillside cave which has a source of iron-rich water. In ancient days, Romans used to travel by boat to the nearby port, Llandudno, and trek some miles inland to Trefriw by horse and cart, to bathe in the waters that are so rich in sulphur and iron.

Today, deep in a mountain stalactite cave known as the Grotto of Wells, water comes dripping through the rock into three wells, and has become a popular, natural, gentle, and absorbable iron supplement. The water is piped underground, down the hill into the Spatone building, passing through several UV lights on its way. The UV lamp sterilizes the water via UV rays, while filters remove any bacteria.

This little bottling plant is nestled in such a picturesque spot that they can’t even extend the building. It’s a well-guarded little cave, locked with iron padlocks to protect it from bio-terrorism. When I arrive, they first show me around the bottling plant, then unlock the cave. We wear waterproof Wellington boots and take flashlights to see the source of the iron water. It rains down into the cave, and gets pumped directly into sachets that are sold worldwide, under the name Spatone Iron Supplements. The concentration of iron in the water coming through the rock is greater in the summer than in the winter, when it becomes diluted by heavy rains. The final marketed product gets adjusted accordingly.

Spatone has become a popular product for the elderly, for expectant mothers, and others who are iron-deficient. There are plenty iron supplements on the market, but mostly they are tablets, where the iron is embedded in carriers which take time for the body to break down. Here, the iron goes straight into the bloodstream, which is far more effective.

The company was interested in getting certification because they’d had many queries from kosher consumers, especially in Israel, who wanted to be sure that nothing else was added to the water. Since it actually tastes very metallic, they’ve started to produce another product, with the addition of apple juice concentrate, which we also supervised and certified, although not for Pesach. The product was so successful in Eretz Yisrael that they now make a special production run with our hechsher and Hebrew packaging.

What strikes me when I visit Trefriw is how a beautiful natural grotto waited centuries for its turn to serve a G-dly purpose, providing a natural iron supplement to Klal Yisrael and all of mankind.

Know Your Onions

Kashrus can’t always be explained, although sometimes it’s actually better that our clients can’t get all the rules of the game straight. Because if you don’t know the rules, you can’t cheat. Like Mr. Tam.

I once arrived in Vietnam to supervise a kosher production run in a tuna factory, where I met Mr. Tam, the owner, who introduced himself by saying, “I was a Vietcong guerrilla, and we won the war against you Americans.”

“Sorry to disappoint you, but I’m British,” I said.

He was as tough as they come, and also found it hard to accept the kashrus rules. “My factory is very hygienic, very safe. What do you need to go to all this bother for?”

“It’s the rules of our religion,” was all I could say. But I knew, both from his aggressive greeting and his scepticism, that he would need close watching.

When it came to making a tuna paste, the recipe called for a lot of onions. “You need to buy onions with peel and roots intact,” I told him. (Otherwise there is an issue of gilui, which applies to onions and garlic left open overnight.)

“Don’t tell me which onions I need to buy, rabbi. I know what onions this product needs.”

And sure enough, his worker came back from the market with crates of peeled, topped-and-tailed onions.

I told him he needed to get these off the factory premises fast and buy onions with roots and peels.

“But this is much easier, it’s the same thing, but already prepared.”

“Look, it’s religion. We’re not allowed.”

“Very complicated, you Jews are.”

“If it is too complicated for you to make this tuna paste, just let us know and we’ll go elsewhere,” I told him.

“No, no, no. Of course, not too complicated. We’ll do it your way.” It was an entire week’s production at a round-the-clock facility, with two mashgichim there full time. Mr. Tam wanted our business.

The next time the worker went to the market, he kept sending me pictures of onions, to check they were okay. He returned with enough onions for the week’s production.

“Rabbi, are you happy with these onions?” the owner double-checked.

“Yes, these are fine,” I told him.

“Then I will get my staff to peel them today.”

“Mr. Tam, sorry, but it doesn’t work that way. Please only peel today what you need for today’s production.”

He was actually taken back. “You can tell me about kosher, but don’t tell me how to run my factory now. This is how to run an efficient production.”

“Mr. Tam, it’s because of the kosher laws. You can’t prepare onions for tomorrow. You can only peel what you will use today.”

“Rabbi, do you really want me to believe that? If it’s kosher today, it’s kosher tomorrow!”

IT WAS LIKE ANALYZING A BLATT GEMARA

The times I traveled along with Dayan Osher Yaakov Westheim ztz”l were always special experiences. People recognized him everywhere and would approach him for a brachah, ask sh’eilos, or offer their help with anything he might need. Just ten months — and another lifetime ago — I traveled with Rav Westheim to the Nestle factory in France. Due to technical issues, the train stopped one station early in Aix-les-Bains, and we were stuck. We went outside the station to find a taxi, but none were available. Soon, though, Jewish passersby noticed the Rav and there was no shortage of offers for the half-hour ride.

Another time, we were en route to Eretz Yisrael and had booked last minute on a budget airline, Jet 2, which operated some flights from Manchester to Tel Aviv. It was right after Pesach and the plane was packed with bochurim and yungeleit making their way back to yeshivah. The Dayan was near the front of the plane and I was at the back. When I got up and went over to speak to him, a line formed behind me. I told him that there was a line of people waiting to converse with him, so he quipped, “Danny, it’s because I’m the only free service on the flight…”

When a factory presented very complex kashrus issues, Dayan Westheim would investigate it himself. He would walk around, looking, listening to the explanations, and quietly consider. Then he would ask very specific questions, and his analytical and creative mind would come up with a halachic solution. I remember being in a huge plant in Ireland that contained very complicated and intricate machinery for creating powders out of certain liquids, and after being shown each machine, every pipe and tank, the Dayan wrote out an exact formula to kosher the factory, with no halachic leniencies, no shortcuts. They were amazed and asked where he had studied food technology and food chemistry. Their own long-time workers didn’t have such a detailed grasp of the processes involved.

I actually asked what he was thinking as he toured the factory, and he told me, “I’m thinking, ‘How would my mechutan, Rav Shmuel Wosner, kasher this? How would the Chazon Ish approach this? How would my rebbi, the Minchas Yitzchak, kasher this?’” He was analysing the process like one analyzes a blatt Gemara.

After the Dayan’s heartbreaking petirah on Erev Shabbos Hagadol from COVID, his shul fundraised to dedicate a sefer Torah in his memory. I sent the link to all those in the kashrus and food industries who had a connection to the Dayan, because I knew that they all held him in great esteem. On a whim, one of the people I included was an Irish gentile, Mr. Murphy. Badatz Iggud Harabbonim has not supervised meat for over five years, but when we did have our own shechitah, it was done in Ireland, and Mr. Murphy was our main local contact. I didn’t know him personally, because I never worked directly with the shochtim or the meat division, but I figured that he had known Rav Osher.

I was shocked when Murphy responded with 1,800 Euros for the campaign.

Gentiles don’t usually have such musagim of charity — they consider £10 a reasonable donation. I thanked him very warmly and said, “You really surprised me.”

He said, “In our community, we don’t really give in that style, and I hadn’t seen Rabbi Westheim in years. But I have never forgotten him. He left such an impression on me that I just had to give generously.”

It wasn’t money we could use for the actual sefer, but it will go to other charitable needs in the Dayan’s memory.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 850)

Oops! We could not locate your form.