Talmud Yerushalmi Finally Gets Its Crown

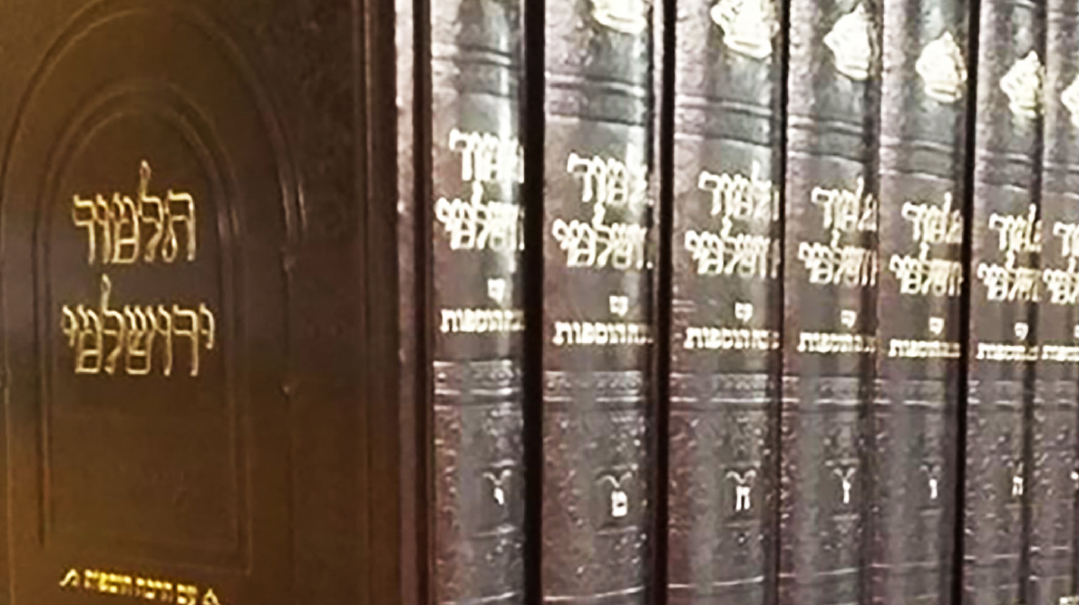

| November 26, 2024Thanks to Dirshu, Oz Vehadar, and ArtScroll, the year 5782 saw a great awakening in the study of Talmud Yerushalmi

This week, those who study Talmud Yerushalmi will reach a great milestone. November 27 sees the siyum of Maseches Bikkurim and the final element of Seder Zeraim. The last two years have ranged from the easier Berachos and Maaser Sheini to the more difficult Demai, Kila’im, and Orlah. Many who started this limud in 2022 can now look forward to beginning Seder Moed.

This milestone holds great meaning for me on a personal level. I have been giving a Yerushalmi shiur for the last nine years, following 17 years of giving a Daf Yomi shiur. Though it was difficult at first, I have found it to be a wonderful limud and have enjoyed it immensely. For seven years, I gave the Yerushalmi shiurim on an irregular basis. Two years ago, I established a regular schedule of three shiurim a week in which we covered seven blatt.

The foray into Talmud Yerushalmi presented many questions. Where should I start? How many pages are there? What commentaries are there? How long is the cycle I should follow? Who can I turn to if I have a question?

At that stage, the only cycle for learning Yerushalmi was the one instituted by the Lev Simchah of Gur: four years, following the page numbers of the Vilna edition. (References to Yerushalmi, however, always cite perek and halachah, unlike references to Bavli, which are tied to page numbers.) The cycle came about after the Lev Simchah gave a speech in 5740 that referred to the same story of Rabi Akiva being saved by holding on to a board of a boat (Yevamos 121a) that Rav Meir Shapiro cited when he started the Daf Yomi program for Bavli. The Lev Simchah pointed out that daf shel sefinah — “board of a boat” — has the same gematria as Talmud Yerushalmi.

Together with a group of six others, we began a daily shiur in Yerushalmi using the ArtScroll edition, whose pages are less daunting than the Vilna edition. It was the beginning of a journey into the unknown, but one that I certainly don’t regret.

The only familiarity many have with Yerushalmi is Maseches Shekalim. The Daf Yomi cycle switches over to Yerushalmi for that one masechta, because it is the only one in Seder Moed that lacks Talmud Bavli. But aside from that, Yerushalmi is only studied by a fraction of those who learn Bavli.

There is good reason for this. The wording tends to be terse and concise. There are those who theorize that, due to constant persecution by the Romans, it was never properly finalized the way that Bavli was, with many amendments and clarifications.

Indeed, the Vilna edition is very difficult to learn, despite the few Acharonim that we have on the page. You learn a piece, then you must discern if the piece following it is a proof to the preceding, a question, or an entirely new piece not related to the preceding.

Another reason the Yerushalmi has not been widely learned is that the Bavli came later, and the Rishonim gave it more importance precisely for this reason; they felt that the Bavli had rejected some of the conclusions of the Yerushalmi and reached their own decisions accordingly. In fact, some Rishonim, most notably Rashi, did not have access to Talmud Yerushalmi at all (although Rambam, Rabbeinu Chananel, and Baalei Tosafos did).

Even the texts that we have show signs of missing elements; the various kisvei yad from Venice to Leiden, Rome, and Ascoreal do not always match up, and the correct girsa is not always clear. There is a sugya that ends cryptically with the words “av beis din.” What this actually means is that one should insert a separate Gemara from Berachos that discusses an argument between Rav Gamliel and Rav Yehoshua, with Rav Eliezer ben Azarya becoming the av beis din. (As per the Yerushalmi version of that episode. Bavli reports this as a disagreement regarding the post of rosh yeshivah rather than av beis din).

And always expect the unexpected. Take, for example, the din that we learn from Maseches Rosh Hashanah not to blow the shofar on Shabbos. We learn in Talmud Bavli that this was a gezeirah from the Chachamim due to the fear that one may come to carry the shofar in the street. But the Yerushalmi holds that it is forbidden from the Torah, due to the words “zichron teruah.” These words connote that there are times you do not blow — rather, you invoke a “remembrance” of the blowing, by reciting the pesukim of Shofros. (This view is recorded in Bavli as well, but is then rejected.)

There is a similar difference with regard to the reason we do not read the Megillah on Shabbos. We assume it is because we fear one might carry the Megillah without an eiruv. But the Yerushalmi holds that the reason is that it was forbidden to learn Kesuvim on Shabbos when the shiur was being given in shul (this idea is referred to in Bavli Shabbos).

While each section of a perek in Bavli is called a mishnah, in Yerushalmi it is referred to as a “halachah.” One might immediately assume that the “mishnah” in Bavli and the “halachah” in Yerushalmi are one and the same. But this isn’t so. There are close to 800 differences in the wording between the two, though not all of them are material.

In Yerushalmi, Bava Metzia’s fourth perek is titled Hakesef rather than Hazahav. In Maseches Shabbos, Yerushalmi only has comments on 20 of the 24 perakim, and in Maseches Makkos, there is only commentary on two of the three perakim.

I owe eternal hakaras hatov to Rav Yosef Gavriel Bechhofer for helping me navigate through Talmud Yerushalmi. Rav Gavriel is a trailblazer, having given 741 shiurim on Yerushalmi from 2002 to 2006 — before the ArtScroll revolution. His expertise was indeed a blessing. I got in touch with Rav Bechhofer, he spoke at our siyumim occasionally, and he is still giving shiurim in Yerushalmi on various platforms.

I made my own full siyum on Talmud Yerushalmi in 2020, and we managed to record shiurim of the whole first cycle on the Kol Halashon network, using the Vilna page numbers.

Thanks to Dirshu, Oz Vehadar, and ArtScroll, the year 5782 saw a great awakening in the study of Talmud Yerushalmi. November of that year saw the start of a new cycle, but this time an alternative new cycle was also instituted, in line with the Artscroll and Oz Vehadar pages. Through this cycle, Yerushalmi could be completed in five and three-quarter years.

Now, after two years, we find ourselves finishing Seder Zeraim. It is a celebration of much work, effort, and accomplishment, but along with it comes a very special feeling. Because once all the difficulties are overcome, one comes to recognize that Yerushalmi is truly special.

Rav Moshe Zacuto (in his commentary to Rav Chaim Vital’s Mevo Hashearim) writes that the Yerushalmi holds more secrets than the Bavli. The Netziv (Ha’amek Davar, Shemos 34a) writes that Yerushalmi is on a higher level than the Bavli — it was written earlier and compiled in Eretz Yisrael. He likens the relationship between Talmud Yerushalmi and Talmud Bavli to that of the first Luchos and the second Luchos.

In the words of the the Chida (Midbar Kedeimos, ches, No. 2), “The earlier generations were comprised of more elevated souls who were able to plumb the depths without tremendous debate and argumentation.” The Chida elsewhere (Sheim Hagedolim, seforim taf, No. 56) attributes the Rambam’s lofty soul to his connection to the Talmud Yerushalmi. The Gemara in Sanhedrin (24a) refers to Talmud Bavli as “machashakim” — darkness.

Rav Yosef Shaul Nathanson (commentary to Aggados, Yoma 9a) also understands that this darkness results from the doubts that emerge from pilpul and much machlokes — unlike the Yerushalmi. The Yerushalmi is referred to as a state of noam — pleasantness. A term frequently used in Talmud Bavli is maskif — “he asked fiercely.” You will not find this term anywhere in the Yerushalmi.

Rav Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld once shared a stunning gematria. The pasuk in Yeshayahu (1:27) says, “Tzion b’mishpat tipadeh v’shaveha b’tzedakah — Tzion will be redeemed in judgment, those who return her with tzedakah.”

Rav Yosef Chaim pointed out that the words “v’shaveha b’tzedakah” — which refers to our time in galus — have the gematria of “Talmud Bavli.” The words “Tzion b’mishpat tipadeh,” which refers to the Geulah, have the gematria of “Talmud Yerushalmi.”

When the Brisker Rav heard this, he said that while he was not usually interested in gematrios, this one definitely held true significance. Yerushalmi is somehow connected to the days of the Geulah; in fact, the Sefer Hapardes even states then when Mashiach comes, we will have true clarity and merit to pasken like the Yerushalmi.

Rav Feivel Cohen offers a deep insight into this gematria (this can be found in his letter of approbation in the Hebrew ArtScroll Gemara). We find a difference between Bavli and Yerushalmi in how they express the term “according to.” In Bavli, they use the word “aliba.” In Yerushalmi, they use the word “adaata.” The root of the word aliba is lev — “heart.” This indicates that Bavli is associated with the heart — i.e., emotion. In contrast, the root of “adaata” is daas — “knowledge.” This indicates that Yerushalmi is associated with the intellect.

Thus, the words “v’shaveha b’tzedakah” are gematria Talmud Bavli, as tzedakah is an act of mercy — a faculty of the heart. On the other hand, Talmud Yerushalmi shares the gematria of “Tzion b’mishpat tipadeh” — mishpat meaning judgment, a faculty of the mind.

In the merit of our limud of Yerushalmi, may we soon see the fulfillment of the prophecy of Tzion b’mishpat tipadeh.

Rabbi Y.C.D. (Yitzchak Chaim Dovid) Cohen has been giving shiurim for many years in Daf Yomi and Yerushalmi. He works in mortgages and financial management. He lives with his family in Manchester, England.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1038)

Oops! We could not locate your form.