Talking Peace, Preparing for War

Leah and Simcha Goldin, parents of late Israeli soldier Hadar Goldin, and Zehava Shaul, mother of late Israeli soldier Oron Shaul at a press conference outside the Prime Minister's residence in Jerusalem, August 5, 2018, ahead of the cabinet meeting. (Photo: Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

W

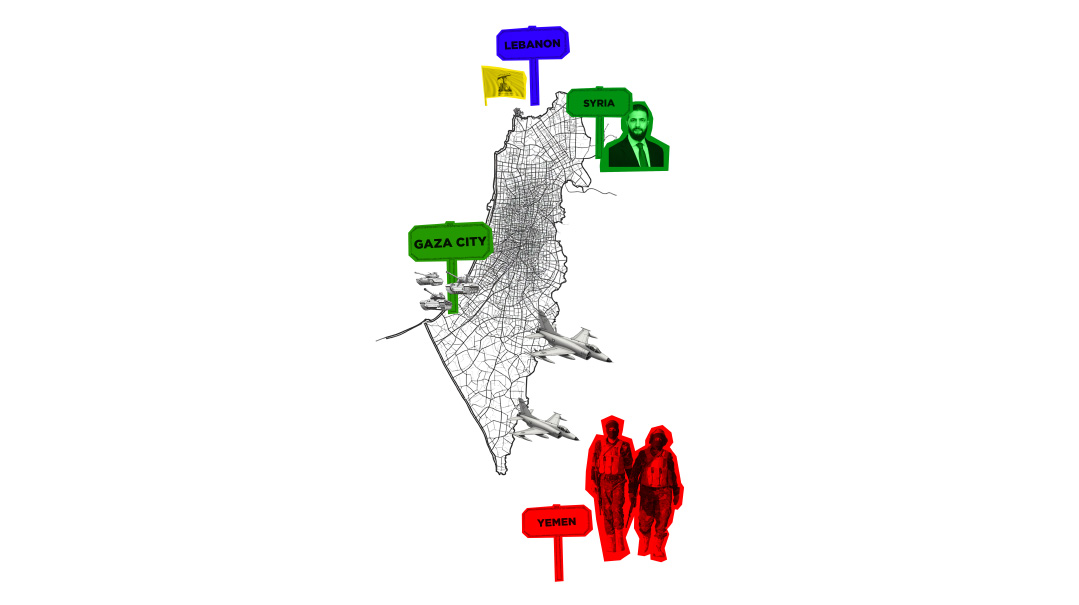

hile on the Israeli side of the border smoke rises from fields lit aflame by burning kites, a different sort of smoke is emanating from Gaza — a diplomatic smokescreen that may indicate Israel, Hamas, and Egypt are coming to a general understanding on a cease-fire.

On the agenda are two proposals — one from Egypt and the other crafted by UN Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process, Nickolay Mladenov.

The Egyptian proposal makes an inter-Palestinian truce between Hamas and Fatah the top priority, followed by exchanges of prisoners and captives — including the bodies of Israel soldiers Oron Shaul and Hadar Goldin Hy”d — and then an agreement for a long-term cease-fire. At a later date, a Palestinian unity government would be established to prepare for elections.

Mladenov’s proposal prioritizes relief for Gaza’s economy, followed by an exchange of prisoners and captives. Under Mladenov’s plan, Israel would allow more goods to enter the Gaza Strip, infuse half a billion dollars to develop the Strip, build desalination and electricity plants, and provide more work permits for Gaza residents.

The two proposals don’t essentially contradict one another, and the Hamas leadership is co-opting principles that appear in both plans. As usual, the devil is in the details. Hamas opposes linking the economic agreements and the cease-fire with the return of captives, bodies, and Palestinian prisoners. It believes those are separate issues that require separate discussions. It is also unclear which country would provide funding for the economic development plan, especially as the Egyptians object to the Qataris playing a leading role.

Egypt is further demanding that the Palestinian Authority hasten the rapprochement process, but Mahmoud Abbas presented a list of 14 reservations that might prevent that from happening. Abbas recently appointed Nabil Abu Rudeineh as deputy prime minister, and Hamas sees this as an indication of Abbas’s opposition to a new unity government. Without a unity government, no rapprochement is possible under the Egyptian plan.

On the other hand, Egypt’s recent decision to open the Rafiach crossing in the absence of an agreement with the PA indicates that Cairo is ready to work independently with Hamas, even if that means the Palestinian movement will continued to be split between Hamas and Fatah. Likewise, Israel’s silence after Egypt opened the crossing (while Israel kept the Kerem Shalom Crossing closed) makes it clear that Jerusalem, like Cairo, may not see the Hamas-Fatah reconciliation as a fundamental condition to opening crossings or lifting the blockade.

Moreover, it appears the split between Fatah and Hamas may actually be playing into Israel’s hands, as it can then conduct purely technical military talks with Hamas without paying a diplomatic price for concessions to the terror group. This assessment is reinforced by the active involvement of Mladenov in the three-way negotiations. In the past, Israel vehemently opposed not only mediation initiatives with Hamas (except when dealing with prisoners and captives), but also meetings between senior international representatives and Hamas officials. Israel has demanded in the past that the PA be the exclusive address for conducting Gaza affairs. Now, not only is Israel encouraging Mladenov, it is using him to present its positions.

This policy indicates that Israel might agree to treat Hamas as the legitimate representative in Gaza, should any new economic and administrative agreements be reached. That would mark a significant turn in relations between Israel and Hamas. Under this sort of agreement, Israel would allow Hamas to conduct trade with manufacturers in Israel and Yehudah and Shomron, and to redefine the framework of the blockade. Israel would also have to accept the possibility that a future Hamas and Fatah government would receive international legitimacy.

At a meeting of the security cabinet on Sunday, Chief of General Staff Gadi Eizenkot told the ministers there was a minimal chance of reaching a long-term agreement in Gaza. Many obstacles that remain, chief among them lack of rapprochement on the Palestinian side. Israel further understands that if Hamas does not achieve a substantial result at the negotiating table, it will be ready to go to war. “The IDF is prepared for any scenario,” Eizenkot told the ministers. (Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 722)

Oops! We could not locate your form.